An Xiao Mina:Hi, everyone. Thank you for having me having me here. My name is An Xiao Mina. You can call me An, and I’m a product designer and an independent researcher and writer based in the Bay, but originally from LA. So I’m psyched to be back here.

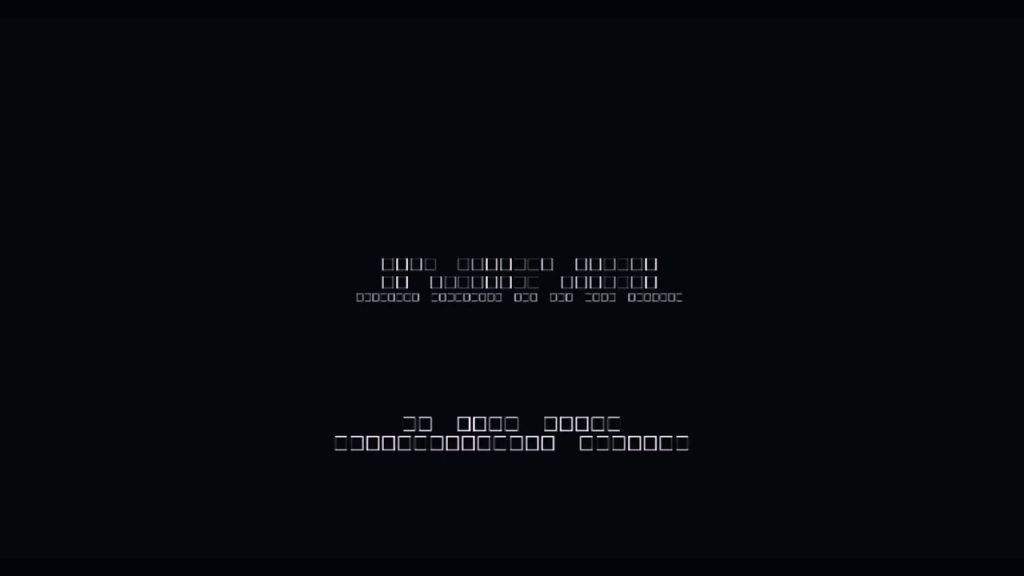

Today I’m talking about different sorts of divides, specifically around language divides, and some biases around language that exist in our technologies and our technological spaces. I wanted take a moment to imagine this “next billion” group of people who are coming online and the sheer diversity of languages that they’re speaking. It’s hundreds and thousands of different languages. And one language might be Khmer, a Cambodian language. A colleague of mine, researcher Ben Valentine, (he’s based in Cambodia) pointed out that when he’s looking at Khmer web sites with certain browsers, the very language, which has its own custom script, appears like this:

It looks like boxes. So literally the language of Khmer is invisible to many technologies. It’s just one example of how the language that you speak shapes the Internet that you have access to, both as a reader and as a speaker.

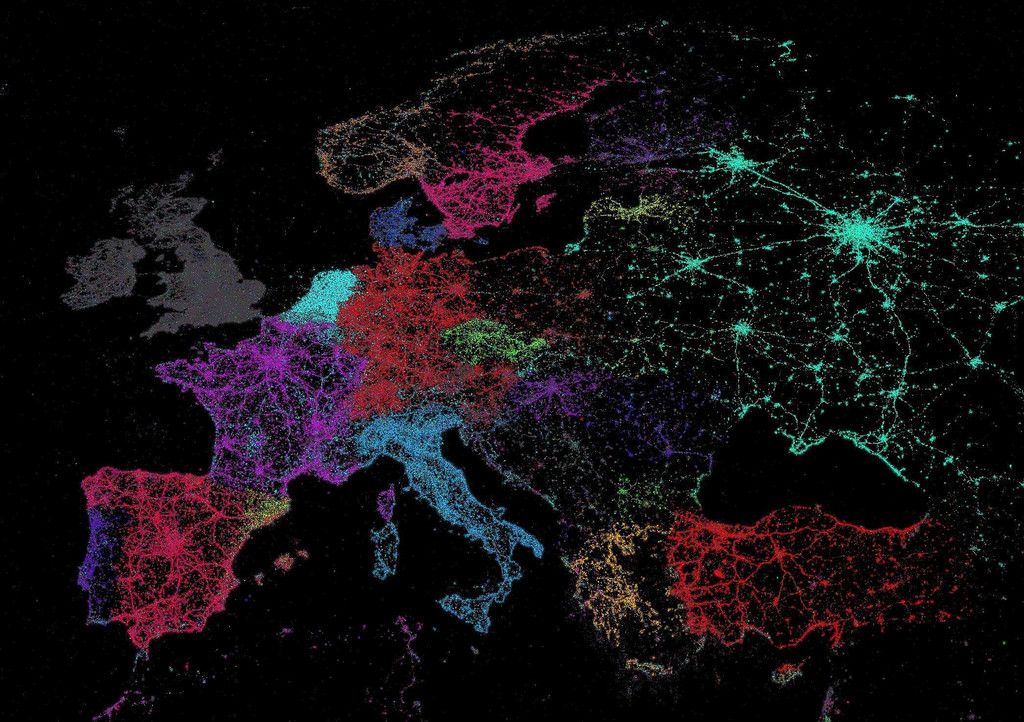

When we think about network graphs and we talk about how the network effects that make up an important part of how social movements and how information is distributed online, there’s this assumption in those visualizations that every node in that network is equal. But very often, and you can slice data in many different way, the languages that we speak actually limit the networks that we have access to and that we’re interacting with.

Image: Frank Jacobs, “Vive le tweet! A Map of Twitter’s Languages”

This is a visualization from 2010 by Mike McDandless, who’s a researcher who scraped the Twitter data for the languages that people are speaking based on their location that they’re tweeting from, and Eric Fischer then visualized this. And you can see how the languages that people are speaking (each color represents a different language), it falls along geopolitical lines. And this is not people just speaking Italian because they’re in Italy, and we’re not visualizing what people are speaking based on this map. It’s actually the language itself recreates the map of Europe. And you can expand this into other countries and other regions as well.

This can have an effect. One specific example of this. So, often people talk about the importance of Wikipedia and the importance of open knowledge and open access to knowledge and the ability to contribute to a collective database of knowledge. Wikipedia has built-in translation features, it allows people to contribute language and translation. But again, if you’re speaking a minority language, your access to that knowledge can be severely limited. These are the numbers of articles available for different languages.

If you’re speaking majority languages, or languages for people who’ve made a concerted effort to translate that content, you have access to millions of articles and it’s a great database. But if you’re speaking—especially minority Asian and African languages, that number starts to drop significantly. Ten thousand for Afrikaans, Tagalog, Kiswahili, and down to a hundred for even smaller minority languages. We can expect similar patterns, I think, with other web sites and other sorts of content, Wikipedia being just one example.

And then in addition to reading, it’s also the access to voice. I think a lot of us are familiar with the Internet in building social movements and the ability to amplify one’s voice. Certainly the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong and Black Lives Matter here in the US rely on the ability to broadcast a message, to use hashtags, to amplify a voice and create a pipeline from social media to mainstream media, and then hopefully to other audiences.

And certainly we can think about major hashtags and major movements that’ve been in English or a majority language. #TweetLikeAForeignJournalist in Kenya was a critique of media coverage of East Africa. And then #JeSuisCharlie, a simple enough French phrase for people to remember and to understand.

But there are a number of other movements in other languages that are more difficult to understand, and get significantly less attention. #sassoufit in Congo. There’s a gau wu (#鳩嗚) movement that’s part of the Hong Kong Umbrella Movement, but is a sort of separate group with sort of different aims and strategies. #lumaddinako, that’s in the Philippines. And then [#مصر_بتفرح] means “Egypt delights,” a parody hashtag which I’ll talk about a little later. These sorts of movements and conversations are often limited to the language sphere that they’re in, because they’re often working with minority languages.

Just to illustrate this even further, I just love this quote from Sarah Kendzior, who’s a writer on social justice in Middle America and Central Asia. She’s speaking about the kind of quandries that an Uzbek activist might have to go through to raise awareness for their cause. I just want to read through the whole description, because it really shows you some of the challenges with amplifying voice when your language is not very well represented in technological platforms, and there’s no pipeline for translating those languages into mainstream and majority media.

If she knows Russian, she has to decide whether writing in Russian—and potentially reaching an international audience as well as the 41 percent of Uzbeks who can read Russian—outweighs not being able to reach non-Russian speaking Uzbeks or seeming to value a foreign language over one’s native tongue.

Sara Kendzior, “Can Minor Languages Make Revolution?”

So even the decision to speak Russian over Uzbek, even though there are benefits to that amplification, there are political consequences to not speaking in Uzbek. And here’s where the availability of fonts, typography, and input systems of the Uzbek language have consequences for political action.

If she writes in Uzbek, she has to choose which alphabet—Cyrillic, to reach older generations and Uzbeks in neighboring former Soviet republics who only know the Cyrillic version? Or Latin, to reach the younger readers who comprise the bulk of Uzbekistan’s Internet users?

Sara Kendzior, “Can Minor Languages Make Revolution?”

So these sorts of dilemmas are much more common when you’re speaking a minority language, especially if that language has non-Latin script.

As a designer as well as a product thinker, I’m also thinking about what are potential solutions. And for provocation and for conversation, I wanted to throw out some potential ideas for how we can think about improving language inclusion [and] language access across the world and also here in the Unites States for people who are speaking many different languages.

One of the possibilities here is crowdsourcing. Crowdsourcing certainly has a lot of problematics. But when you think about the possibilities of translation, machine translation can scale very quickly but it’s often inaccurate. Anyone who’s done translations, even between English and Spanish…it leads to much hilarity. At the same time, the translation model as currently exists just simply cannot scale for the sort of content and conversations that need to be translated.

And again, crowdsourcing can have its problems. This is not a crowdsourced subtitle. This was actually a famous meme, All Your Base Are Belong to Us. But it’s the sort of risk that happens when fansubbing communities translate popular media. Fansubbing is fan subtitling. So an example of translating anime movies into English, or translating American English movies into Chinese can be done by communities, but you have to have a great deal of faith and trust that those translations will be accurate.

At the same time, the fansubbing communities can be very successful, and there are more formalized ways of doing crowdsourced translation that also seem to be having some uptake. TED has the Open Translation Project, where hundreds of volunteers who are translating into hundreds of languages can translate these videos. And we can see similar examples with sites like viki.com, where people can translate content.

And I think part of the risk of crowdsourcing of course is the risk of free labor, and I think we need to talk about what fair compensation looks like. But at the same time a broader model for translation can help ensure that content reaches other languages. Yeeyan in China is another crowdsourced site where people were translating articles from English into Chinese as an important way of increasing access for sites like The Economist. It was shut down, and it’s kind of at a neutral space right now, but it’s an example of the potential for this.

And then my own experience is building a light platform for translating the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei from Chinese into English and his tweets, which back in 2009/2010 were very rarely understood by English speaking media, despite the fact that he had a major media presence. This model kind of shows that maybe just five translators can have an impact with 31,000 followers. So it doesn’t take a lot, but it does take motivation; it does take interest. And we’re trying to productize that at Meedan with a product called Bridge that allows for crowdsourced translation around social media.

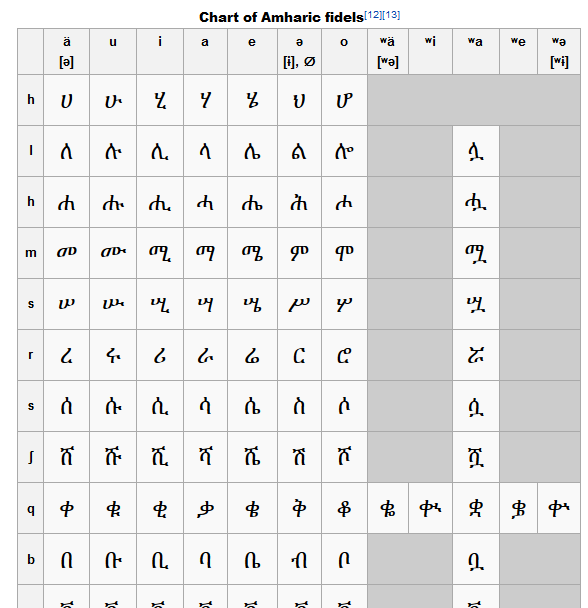

Screenshot of Amharic alphasyllabary via Wikipedia

Secondly, we need to change the structure. Language inequity is a full stack problem. I think you can translate all the things, but if your language is not supported, if your font— This is the Amharic alphabet, with over 300 letters or alphasyllables, and we have to design better ways to input these languages. We need to design better ways to read them, to access them. And we just need a better structure for supporting languages, ensuring that they can be read and input, especially on mobile devices.

One possibility (this is a picture of Leon Messi interacting with an app called WeChat) is we also need to think about audio interactions and audio input. A researcher friend of mine, Christina [?] pointed out that QR codes are very popular in China as a form of input because the very act of typing in a Chinese URL can be burdensome. So it’s much easier to take a screenshot of a QR code. So we need to think about different interactions, and especially when we get to languages that may not have a formal written form or any written form. Audio interaction and oral engagement through technology I think will be very critical and important.

And just to close, I’ll give one example of a bit of color that can be exposed through translation and why this can be both very exciting and interesting, this process of building our global imaginations. Our ability to empathize and interact and value people from other cultures, in different parts of the world that can often be invisible to the West is through bringing out that citizen content, bringing out content that can be interesting and valuable.

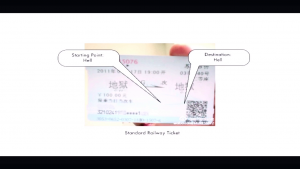

This is just one example. The 2011 Wenzhou train crash in China was a major train crash where hundreds of people were killed and injured. This was the sort of event that would’ve been censored in Chinese media because it potentially an example of government mismanagement. But the role of social media in bringing this out was so compelling, and actually telling the specific stories of this is a way of highlighting how and why these online engagements can be quite powerful. And it really takes translation, though, to highlight these.

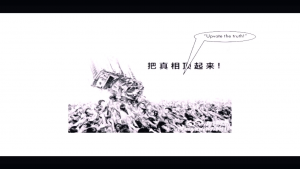

This was one image where someone Photoshopped this into this monster movie. And you can see it’s a kind of parody conversation. “I’d rather believe this than the official explanation for the train crash.” There’s different sorts of memes. “You cannot escape the blame of profaning the dead.”

“Time to disembark. We’re home.” Just kind of poetic messages. This is a friend of mine, who had Photoshopped the train ticket “starting point: Hell, destination point: Hell.” And that specificity of translating this content and bringing it out becomes an important act of journalism, I would say.

Just to close, as we think about the role of language on the Internet, it really biases our experience, and there are a lot of risks and challenges there, especially as people from the Global South are coming online. The ability for them to access content and for them to contribute to important conversations online will be severely limited. It’ll look more like this, and I think some of the most important work we can do in tech is to bring it out into languages that they can understand.

Thank you so much.

Further Reference

“#Egypt_Delights: A Suez Canal Hashtag Largely Missed by English-Speaking Media” by An Xiao.

Later, there were a panel discussion and Q&A session.

Biased Data: A Panel Discussion on Intersectionality and Internet Ethics at the Processing Foundation web site.