Paul Mason: First an introduction from me about the ideas that drove me to write a book called Postcapitalism, and about the very rapidly changing context for those ideas. So, we’ve had Brexit. And then with no particular explanation from the government, Hard Brexit. Then Trump. Coming next, far-right president of Austria. And then Marine Le Pen comes a frighteningly close second in the French presidential elections.

There’s some very interesting and worthwhile root cause analysis going on right now in the media which I’d urge you to read about why this is all happening. The rise of populism. Is it about economic failure, or is it about the challenged identity of white men? And these are very good questions. But I stand by the assertion I made last year when the book came out that the root cause of both those phenomena—the economic failure and frustrations of low wage people, and the failing story of Western democracy—is ultimately down to this:

That neoliberalism is broken. The economic model of the last thirty years. It worked for a bit, dragged the bottom two thirds of the world’s population up the income scale dramatically, facilitated the tech revolution. But it’s stopped working. And in the ten minutes I’ve got I want to just give the 101 explanation of why. A longer version is available in my book and on many many other, longer introductions you can find on you YouTube and various other platforms.

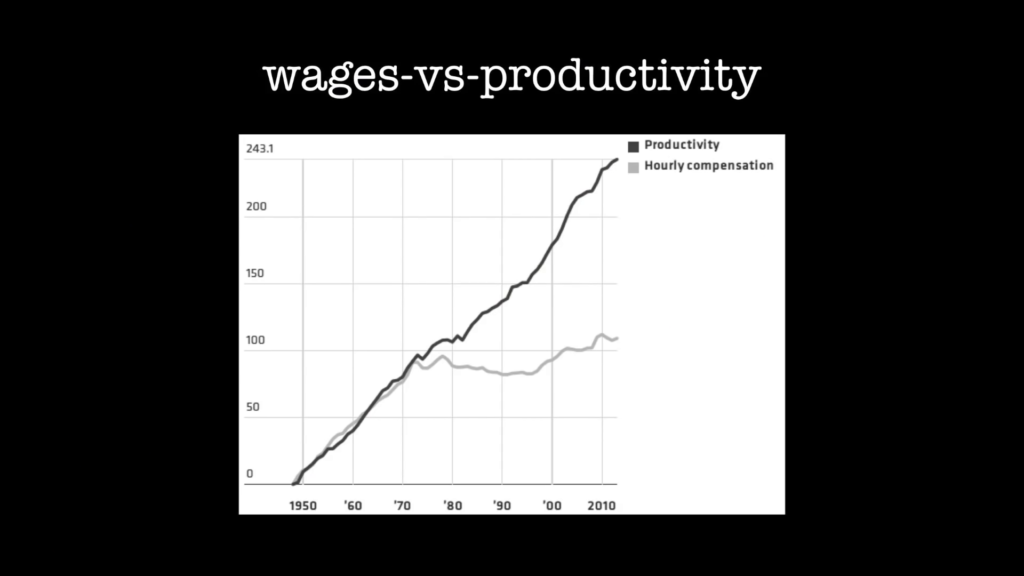

So first issue, wages are stagnating. I hope you can see the gray line. This is US wages but it’s the same story roughly everywhere. Productivity carries on until very recently rising, but wages are stagnating relative to it. And that’s different from what things looked like when (those of you who can remember it) when the kind of Keynesian era was in full swing up to the 70s. So what you end up with as a result of that when wages stagnate, you end up with this:

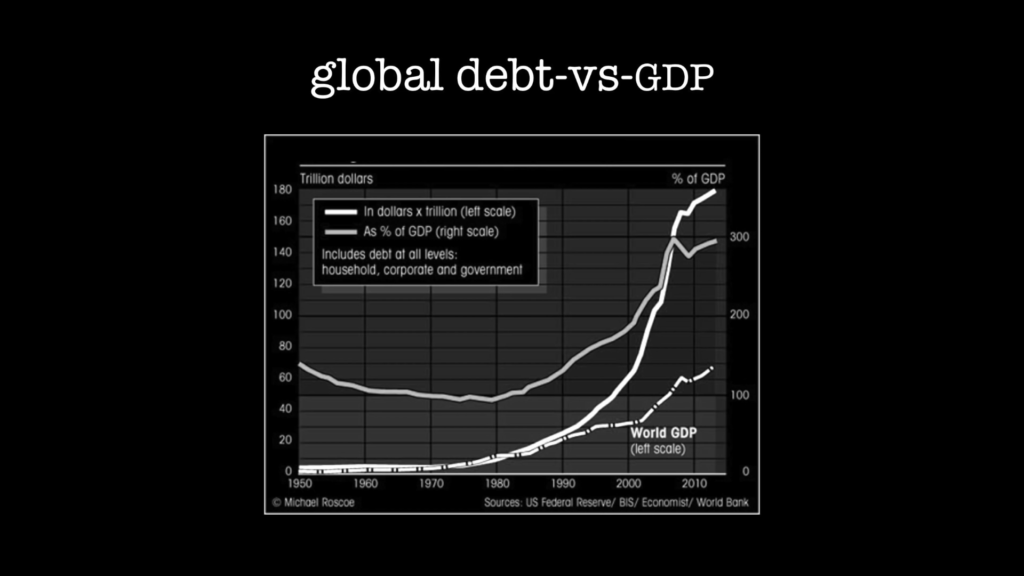

We’ve used debt to drive consumption. So the combined government, private, and corporate debt of the world as shown on this graph has mushroomed to 300% of GDP. And if you look at this line here, this is the percentage line. You read the right-hand axis, 300% of GDP. In 1990 it was 140% of GDP. Now if you’re into trillions, you read the left-hand scale. So you see, world debt and world GDP in trillions, we’re about the same until 1990. There’s world GDP, sixty-something trillions. And there is world debt, 180 trillion.

So…that’s not good. It can’t go on. And what happens of course is because we keep getting boom and bust cycles and entire pension systems go into meltdown, banks have to be saved, welfare states have to, we are told, be wiped out or significantly dismantled, what you then get is one more effect. And that is this:

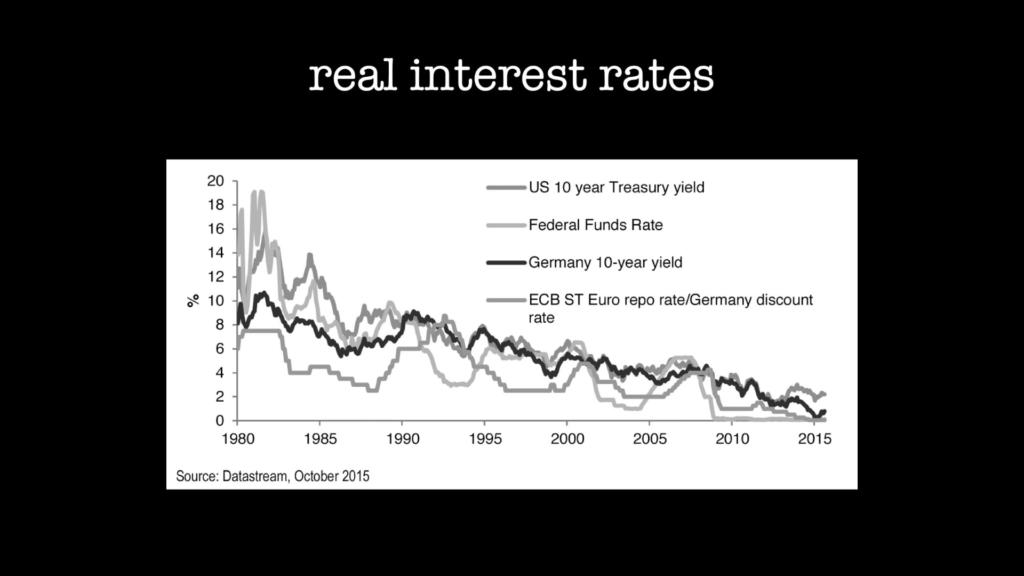

Central banks, to keep the system afloat once it’s started to go wrong, print money. Or they cut interest rates, loosen credit conditions. In general, the answer to failure of growth and crisis is to supply more money to the system. And those of you who understand the fairly rudimentary laws of supply and demand can probably understand this graph. If you increase the supply of money relative to the amount of economic activity that money is there to represent, what is going to happen is that there’s an oversupply of money. And what happens to things that are oversupplied, their price falls. And therefore what this is is the falling price of the safest borrowing on Earth. And it’s fallen roughly towards zero. This is government debt.

And one of my friends in the bond market, you know, a very good mainstream kind of guy, said, “I went to college, did an internship you know twenty years ago, became a bond trader, because I wanted people’s money to grow. Now I oversee the shrinkage of the world’s money, and I don’t like it.” In fact he said to me it doesn’t feel like capitalism.

Now, my explanation for why all this is happening is that capitalism is failing to adapt in the way it did in its most successful periods. In the 1900 to 1914 period. In the post-war period. Because it isn’t creating what we call a high value, high wage, high skill synthesis. It’s not obvious how you make a lot of money if you’re an ordinary person, through getting a job, getting high skills, participating in the most advanced sector of the economy.

Why? Because information technology I argue is different. It’s a very different kind of technology than all other technologies, albeit that it is only machines. Software is a machine. Computers are machines. Silicon chips are machines with three billion switches on them. Together in this room we have more switches than humanity ever created in the whole history of switches.

So they’re just machines, but the scale of their efficiency has changed the game. And I argue that we’re creating new dynamics in terms of price, work and organization. At the heart of the problem is the information effect on prices. Whether you use standard economics or Marxist economics, if something costs almost nothing to reproduce or produce, then under conditions of free competition, its price is going to fall close to what its production cost is. And if that’s zero, its price is going to fall pretty close to zero. Now, capitalism never understood this. Mainstream economics doesn’t— Everything from mainstream economics is scarce. And if you suddenly get a boost of non-scarcity, or what we call abundance, then things like this start happening:

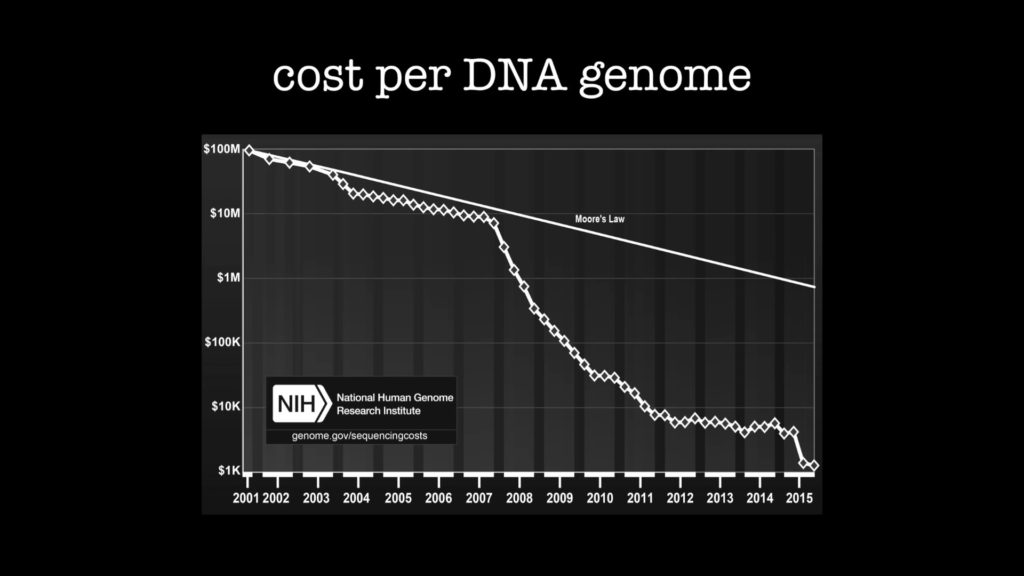

This is just one example I could use. So, never mind the dotted line. The white line is Moore’s Law. The white line is the spectacular technological progress you have lived through. That’s the rate of computer technology. And until 2007, the cost of sequencing DNA roughly tracked it. And then, the information effect kicks in. And so the cost of sequencing an entire genome of DNA falls from $100 million to $0.001 million, or $1,000.

That’s the price effect on information. If you thought your kids were going to have high-paid, high-value jobs in mass kind of factories sequencing DNA, they’re not. And we could start here and go the same scale again, and we’ll follow the same thing toward zero.

So there is a survival mechanism capitalism has against this zero marginal cost effect, which is to create massive monopolies which then capture the value and the network effects of shared information. And as we’ll hear about, one of the key tactics in the last five years of those monopolies has been to smash and grab their way into markets that should really be seeing massive price falls to the benefit of the consumer. I doubt whether this, the so-called unicorns, the platforms, the multi-billion dollar companies based on simple algorithms, can survive what’s going to happen.

Now, the second dynamic is about work. Forty-seven percent of all jobs are now susceptible to automation in the next twenty years. And that’s really before full artificial intelligence kicks in. And yet we don’t eradicate low-paid, repetitive jobs. We go on creating them, because the system we’ve got—low-wage system—incentivizes their creation. We create what the anthropologist David Graeber has called millions of “bullshit jobs.” Jobs that don’t need to exist. The word “carwash,” instead of a machine—that’s what a carwash was thirty years ago—is now five guys with rags. Because five guys with rags can undercut the machine.

So productivity is not rising. It’s stagnating in many countries. Because you can make the most vast productivity gains like the one I just described there in DNA sequencing, but then you just employ people— Walk around the streets of Brighton and see what people are employed doing. Graduates serving coffee.

So finally, information lowers the barriers to all kinds of organizational innovation and allows the creation of horizontal, relatively non-managed business models and the rise of open source. And today, one of the big themes of the people we’ve drawn together is not people who are doing this for ideological reasons. I mean, my book is an ideological intervention into this which ends with a call for regulating the economy to facilitate these kind of businesses. But first of all we have to understand what those businesses are.

That’s the basic thesis of Postcapitalism, that it’s possible. And I go around the world telling people who will listen. Which sometimes includes the Shadow Chancellor, the mayor of Barcelona, the Chancellor of Austria, that promising people high value jobs in the future if only we vote for X, Y, or Z party is not enough to solve the problem that we’re all now faced with. We have to redesign the system and begin regulating in favor of innovation and business creation along the lines of some of the ones that we’re going to hear from today.

I’m reminded that this space was the Prince Regent’s stable. It was where he was being taught to ride. If you’re wondering how he rode in a small space like this, it’s double the length, as you’ll see at lunchtime. It’s a big long hall. And while George IV, the future George IV was trotting around this very space, somebody probably mentioned to him factories. There’s these things called factories. And they were mainly nestled in small places by rivers at the time, before steam comes in. And somebody says, “You know what, we like these. It’s going to cause a lot of disruption but we’re gonna really promote these.” And George IV probably said, “Yeah fine. Carry on. Pass the port, darling.”

I think we have to be a little bit less insouciant than that. We have to say look, there’s this new thing, the collaborative economy. And we have to regulate in its favor as strongly as early 19th century governments regulated in favor of capitalism itself. I call it postcapitalism. I envisage a relatively long transition towards abundance in various sectors. The endpoint is free machines, little compulsory work, a renewable energy system, and high circularity in the use of natural resources.

The good news is that it’s possible and some people are beginning to work out how to do it at scale. The bad news is a lot of people wedded to old business models don’t get it. Many of you will work with them. And because we have a political and social elite who think this present system, the free market system based on high finance, high complexity, and low wages was the most perfect possible system ever to be imagined, we haven’t yet seen a big break in elite thinking. And I think this has to come now, because as we’re all confronting, many people are just no longer willing to go on with the system as it is and they’re choosing reactionary outcomes.

And so we have to basically face the fact that if we don’t grasp the opportunity at governmental level and intergovernmental level, and think about a new model of the economy and society, what people are going to do is start voting against— I said this a year ago when the book came out. Wrote it two years ago when I finished the first draft. If you don’t go beyond the present model, people will start to vote to break up globalization. And I want to defend globalization but change the model.

What we’re living through is a 500-year event. That could be very very difficult to get your head around. Fifty years is a big number for economists. Five years is what they’re comfortable with.

But this guy had mental tools to understand it. Francis Bacon, the founder of the scientific method. This is what he wrote in 1620. That “gunpowder, printing and the compass have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world.” It’s a crude form of technological determinism. But he was right.

To finish, what happens to business in this transition? Well, I think that you have to start thinking about the economy as a combination of the market and the state (which is what economics is all about now), and the nonmarket. The nonmarket for economics is everything you do in your shed. It only matters to them if you happen to buy a Hornby train set, or an Airfix model to make in your shed. This is leisure time. This is noneconomic.

But for postcapitalism and the postcapitalist theory, the nonmarket is equally important. And what we’re looking for is a transition in which we can measure the inputs and outputs of humanity in these three buckets, and the only thing we can use to measure it, I argue, is work. Work is the only thing that Wikipedia or an open source programmer has in common with taxation and market activity. Because there’s no money involved in many of the business and activities that go on here in the nonmarket.

The transition path I think involves the embrace of automation. If we dissociate work and incomes, because we’re going to have to, we’re going to have to try and find ways of giving people incomes and therefore as a transition measure I argue for the citizen’s basic income. I also think the state is going to have to begin providing cheap basic goods. Because a precariously-employed workforce can’t live— In fact, giving them a 5% pay rise is not so happy for them as giving them free transport, or free college education. Open source; we have to promote it and prefer it. And we have to, as we’ll hear later, attack and find alternatives to rent-seeking businesses that simply squat on top of the technological advances we’re living through and extract extra money for them and not exploit their potential.

So that is my time up for my kind of vision of the future. It’s a quick run-through. And I hope we’ll be able to— There’s no Q&A. Louise has designed it so there’s no Q&A. But hopefully in the discussions and over lunch, which is very structured as well, you’ll be able to have a Q&A between bites of your falafel or whatever it is.

Further Reference

Meaning 2016 archived conference web site and Paul Mason profile