It is so good to be here with all of you. And yes I will be calling on people. Mostly those of you standing in the back. I always know why people are standing in the back. That’s what teachers do.

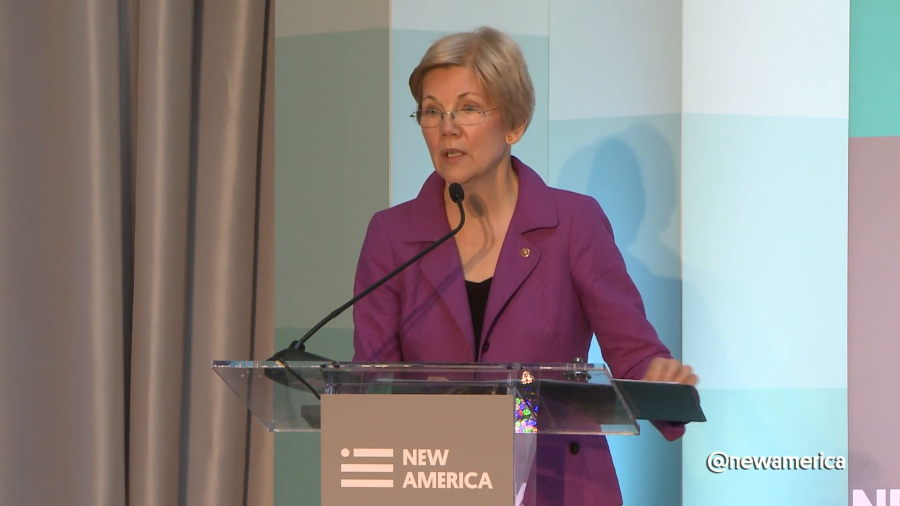

But thank you. And thank you for the introduction, Anne-Marie [Slaughter]. Thank you to the New America Foundation for inviting me here today to talk about the gig economy. This is actually speech I’ve wanted to give for a long time, so I’m glad I have the chance to do it. It’s something we’ve been working on. You know, across the country, new companies are using the Internet to transform the way that Americans work, shop, socialize, vacation, look for love, talk to the doctor, get around, and track down ten-foot feather boas, which is actually my latest search on Amazon. It’s a long story. It’s actually true.

These innovations have helped improve our lives in countless ways, reducing inefficiencies and leveraging network effects to help grow our economy. And this is real growth. For example, increasing broadband penetration boosts GDP. And increasing 3G connections increases mobile data use, which in turn increases GDP. The most famous example of this is probably the ride-sharing platforms in our cities. The taxi cab industry was riddled with monopolies, rents, inefficiencies. Cities limited the number of taxi licenses. They charged drivers steep fees for taxi medallions. They required drivers to pay additional fees to pick up passengers at the airport. They micro-managed paint jobs for individual cars, and even outlawed price competition.

Uber and Lyft, two ride-sharing platforms came onto the scene about five years ago, radically altered this model, enabling anyone with a smartphone and a car to deliver rides. They also enabled customers to find a ride any time of day with the touch of a button. The result was more rides, cheaper rides, and shorter wait times.

The ride-sharing story illustrates the promise of these new businesses. And the dangers. Uber and Lyft fought against local taxi cab rules that kept prices high and limited access to services. But as the dispute in Austin, Texas has demonstrated, the companies have fought just as vigorously against local rules designed to create a level playing field between themselves and their taxi competitors. And they have also resisted rules designed to promote rider safety and driver accountability.

And while their businesses provide workers with greater flexibility, companies like Lyft and Uber have often resisted efforts of those very same workers to try to access a greater share of the wealth that is generated from the work that they do. Their business model is, in part, dependent on extremely low wages for their drivers.

Now look, it is exciting and very hip to talk about Uber and Lyft and TaskRabbit and a whole bunch of other new platforms out there. But the promise and the risks of these companies isn’t new. For centuries, technological advances have helped create new wealth and have increased GDP. But it is policy, rules and regulations, that will determine whether workers have a meaningful opportunity to share in the wealth that is generated.

A century ago, the Industrial Revolution radically altered the American economy. Millions moved from farms to factories. These sweeping changes in our economy generated enormous wealth. They also wreaked havoc on workers and their families. Workplaces were monstrously unsafe. Wages were paltry. Hours were grueling.

Now, America’s response wasn’t too abandon technological innovations and improvements from the Industrial Revolution. We didn’t send everyone back to the farms. No. Instead we came together, and through our government, we changed public policies to adapt to a changing economy, to try to keep the good and get rid of the bad. The list of new laws and regulations was long. Think about it: minimum wage, workplace safety, worker compensation, child labor laws, the 40-hour work week, Social Security, the right to unionize. But each of those changes made a profound difference. They put guard rails around the ability of giant corporations to exploit workers, to generate additional profits at any cost. They helped make sure that part of the increased wealth that was generated by innovation would be used to build a strong middle class.

The changes, by the way, were not all focused on workers. Antitrust laws and newly-created public utilities addressed the new technological revolution’s tendency toward concentration and monopoly, and kept our markets competitive. Rules to prevent cheating and fraud were added to make sure that bad actors in the marketplace couldn’t get a leg up over folks who played by the rules.

Now, those changes didn’t happen overnight. There were big fights over decades to establish that balance. But once in place, these policies underwrote the widely-shared growth and prosperity of the 20th century. I just want to put one number in front of you. From 1935 to 1980, the 90% of America, everybody not in the top 10%, got 70% of all income growth generated in this economy. In other words, as the economy grew and became more productive, so did the average worker’s wages. Instead of all the wealth going to a handful of giant companies, factory owners, and investors—the robber barons of the early 20th century—the growth created by our manufacturing economy supported the growth of a prosperous, secure middle class. And this distribution occurred because of a newly emerging, basic bargain for workers.

A hundred years ago, nobody grappling with the rapid changes in technology and work seriously entertained the idea of banning manufacturing advances. And today, nobody seriously entertains the idea of pulling the plug on the Internet. Massive technological change is a gift, a byproduct of human ingenuity. And it creates extraordinary opportunities to improve the lives of billions of people.

But history shows that to harness those opportunities, to create and sustain a strong middle class, policy also matters. To fully realize the potential of this new economy, laws must be adapted to make sure that the basic bargain for workers remains intact. And that workers have a chance to share in the growth that they helped produce.

Now, the challenge today is doubly difficult. At the same time that we need to adapt to new work relationships in a gig economy, the basic bargain of the old work relationships has become badly frayed. Over the past three decades, workers have been under merciless attack. For decades now, big business has tried to squeeze more profits out of workers by ducking and dodging regulations and by taking advantage of loopholes in employment policy, by skirting enforcement efforts, and even by flagrantly violating the law. Giant corporations have deployed armies of lobbyists and lawyers to freeze, to limit, to dismantle, as many worker protections as they could. And the result is that for decades the guard rails that once served to build a robust middle class no longer offer the same kind of protection.

More and more of today’s jobs have sharply-limited protections and benefits. Look, long before anybody ever wrote an article about the gig economy, corporations had discovered the higher profits they could wring out of an on-demand work force made up of independent contractors. Labor laws make sharp distinctions between employees on the one hand and independent contractors on the other. And the consequence of this is that many employers figured out how to exploit that distinction between the two. They hired people who once were characterized as employees, now to become independent contractors. And the result was that these workers lost their benefit, they lost the stability of guaranteed work, and they lost the ability to form a union and bargain collectively.

But the employee/1099 divide is not the only way that the basic bargain is fraying. Employees, particularly low wage employees, face challenges that are not unlike the challenges facing gig workers and independent contractors. They too have lost both the benefits and the stability of a guaranteed work schedule and a steady income. As employers have moved to just-in-time staffing, more hourly workers are trapped in part-time jobs or stripped down full-time jobs. An increasing number of workers are in subcontracting or franchise arrangements, where their employment conditions are controlled by firms they can’t bargain with, they can’t hold them accountable for even basic safety or wage protection. They may not even actually know the name of their employers.

At the same time that the bargain with workers has become increasingly one-sided for millions of independent contractors and hourly employees, yet another part of the basic economic bargain has also begun to fray. The safety net (unemployment insurance, worker’s comp, Social Security) hasn’t been updated to fill in the holes that employers have created. Temporary workers, contract worker, seasonal workers, permatemps, and part-time workers rarely have access to these benefits. Which means that the workers who most need the safety net are the very ones who are least likely to have it.

Let’s be clear. The gig economy didn’t invent any of these problems. In fact, the gig economy has become a stopgap for some workers who can’t make ends meet in a weak labor market. The much-touted virtues of flexibility, independence, and creativity offered by gig work might be true for some workers in some conditions. But for many, the gig economy is simply the next step in a losing effort to build some economic security in a world where all of the benefits and wealth are floating to the top 10%.

The problems facing gig workers are much like the problems facing millions of other workers. An outdated employee benefits model makes it all but impossible for temporary workers, contract workers, part-time workers, and workers in industries like retail or construction, who switch jobs frequently, to build any economic security. So, just as this country did a hundred years ago, it’s time to rethink the basic bargain between workers and companies. As greater wealth is generated by new technology, how can we ensure that the workers who support the economy can actually share in the wealth?

Well, I believe we start with one simple principle. All workers, no matter where they work, no matter how they work, no matter when they work, no matter who they work for, whether they pick tomatoes or build rocket ships, all workers should have some basic protections and be able to build some economic security for themselves and their families. No worker should fall through the cracks. And here are some ideas about how to rethink and strengthen the worker’s bargain.

We can start by strengthening our safety net so that it catches anyone who has fallen on hard times, whether they have a formal employer or not. And there are three much-needed changes right off the bat on this.

First, make sure that every worker pays into Social Security, as the law has always intended. Right now, it is a challenge for someone who doesn’t have an employer that automatically deducts payroll taxes to pay into Social Security. This can affect both a worker’s ability to qualify for disability insurance after a major [injury], and it can result in much lower retirement benefits. If Social Security is to be fully funded for generations to come, and if all workers are to have adequate benefits, then electronic, automatic, mandatory withholding of payroll taxes must apply to everyone, gig workers, 1099 workers, and hourly employees. That’s the starting place.

Second, every worker should be covered by catastrophic insurance. Workers who have serious accidents or suffer from illnesses that knock them out of the labor market for an extended period need a backstop. And everyone means everyone. Even workers who haven’t built up enough credit for disability insurance. Even workers who don’t have traditional worker’s compensation. This type of insurance should be relatively cheap if it is pooled across the entire workforce through small, regular, automatically-deducted contributions.

And third, all workers, no matter where they work or who they work for, should have some paid leave. Any worker should be able to stay home when they’re sick, or take off some time to care for a sick baby without worrying that that means they won’t be able to make the rent. We can debate where to draw the lines, but let’s start with two ideas. First, each worker should be able to accrue proportional credits toward a certain number of days a year, for any purpose. And second, workers should have some paid family and medical leave to insure against longer absences, such as more serious illnesses, or to care for a newborn baby.

These three, Social Security, catastrophic insurance, and earned leave, create a safety net for income. Together, they give families some protection in an ever more volatile work environment. And they help ensure that after a lifetime of work, people will face their retirement years with some dignity.

Now, the second area of change to make is on employee benefits, both for healthcare and retirement. To make them fully portable. They belong to the worker, no matter what company or platform generates the income, they should follow that worker wherever that worker goes. And the corollary to this is that workers without formal employers should have access to the same kinds of benefits that some employees already have.

I want to be clear here. The Affordable Care Act is a big step toward addressing this problem for healthcare. Providing access for workers who don’t have employer-sponsored coverage and providing a long term structure for portability. We should improve on that structure, enhancing its portability, and reducing the managerial involvement of employers.

There is no similarly portable structure for retirement benefits. One change that would make a really big difference here is a high-quality retirement plan for independent contractors, self-employed workers, and other workers who have no access to retirement benefits, to supplement their Social Security. This plan should use best-in-class practices when it comes to asset allocation, governance structure, and fee transparency. It should be operated solely in the interest of workers and retirees, and those workers and retirees should have a voice in how the plan is run.

Instead of an employer-sponsored 401k, this plan could be run by a union or other organization that could contract investment management to the private sector, just like companies like General Motors contract with providers like Fidelity to offer 401k in the employment setting. And because of the amazing advances in online investment platforms and electronic payroll systems, individuals could set up automatic contributions. It’s time for all workers to have access to the same low-cost, well-protected retirement products that right now only some employers and unions are able to provide.

The benefits to workers from gaining access to health insurance into retirement plans are pretty obvious, but I also want to note the benefits to employers are also substantial. Those employers can shed managerial responsibilities that are peripheral to their businesses. And small businesses and startups can compete for workers without needing to get into the health insurance and retirement business. That is how competitive markets should work.

And the third big area. It’s time to create some legal and regulatory certainty in the labor market. If it is done right, it will be possible to reduce the red tape for large employers, small business owners, and entrepreneurs. We can cut their costs and make it easier for them to employ people. Less ambiguity will also help make sure that some employers don’t exploit loopholes to gain competitive advantages.

And here are four ways to make progress in that area. Okay, you wanted it all. We’re going to do it all at once.

First, enforce the laws already on the books. Can I just have an amen around that? Employers should not be misclassifying workers to keep labor costs down, because they shouldn’t have the chance to hide behind complex arrangements like franchising and subcontracting to skirt their responsibilities to their workers. The many employers who treat their employees well shouldn’t have to compete against the ones who don’t. That’s not a level playing field. That’s a broken system.

Second, streamline the labor laws. Currently, there are endless legal definitions of an employee, depending on the worker’s industry and occupation. The boundaries between employees, contract workers, and gig workers are complex. Providing a wider safety net and more consistent access to retirement and health benefits will reduce the huge impact of different classifications. But at the same time, harmonizing these definitions will mean less regulatory burden for businesses and fewer opportunities for misclassifying workers.

And third, wherever possible, streamline laws at the federal level, so that employers operating across state lines don’t have to jump through crazy number of hoops when they employ workers from more than one state. A small business owner with workers in several states shouldn’t have to spend her valuable time struggling to master different state regulations.

And fourth, every worker should have the right to organize, period. Full-time, part-time, temp workers, gig workers, contract workers, you bet. Those who provide the labor should have the right to bargain as a group with whoever controls the terms of their work. And they should be protected from retaliation or discrimination when they do so. Government is not the only advocate on behalf of workers. It was workers, bargaining through their unions, who helped introduce retirement benefits, sick pay, overtime, the weekend, and a long list of other benefits, for their members and for all workers across this country. Unions helped build America’s middle class, and unions will help rebuild America’s middle class.

And one more thing. A 21st century economy, once again can grow a thriving middle class, but only if we make a few other changes. It will require making investments in education and training. In infrastructure and basic research and development. Today’s high-tech jobs might be located on the factory floor or in a medical lab. But whatever the work sites look like, the workers increasingly need post-secondary education.

So let’s be clear: to build a well educated versatile workforce that this country will need in the 21st century, it is critical that we stop saddling tomorrow’s workers with student debt. Student loan debt has now ballooned to $1.3 trillion. Today, 70% of college grads must borrow money to make it through school. That is not a leg up, that is an anvil dragging workers down.

But I want to make it clear, this is about more than traditional college. American workers will need access to affordable life-long working and retooling for their jobs. Jobs that emerge long after they’ve left school, but long before they retire. I know New America is making important contributions on this topic, with both Opportunity@Work and its education program. You know, people who have worked 20+ years in a changing field should have access to education and training opportunities that will offer new ways to use their talents, their creativity, and their experience. America will need these workers, and these workers will need training.

Now for many of these proposals, government may set policies. But employers, educators, unions, nonprofits, tech innovators, all have critical roles to play. If we’re going to rebuild America’s economy by strengthening American workers, it’s going to take all hands on deck.

But I want to put one more thing on the table before I leave on this. Government investments are one of the most reliable sparks of technological innovation and growth around. Building basic infrastructure, roads and bridges, but also power grids, communication links, mass transit, make it possible for the economy to flourish. Investments in basic research provide a foundation for tomorrow’s advances. A stronger economy will produce more demand for workers that will create opportunities for millions more Americans.

We can’t blame the parts of the gig economy that we don’t like on technology companies, software, or smartphones. There are plenty of outsourced janitors and warehouse workers. Plenty of security guards and manufacturing workers who can explain that on-demand work is nothing new in America. In a healthy economy, disruption is inevitable. But disruption means it is time to adapt to changing circumstances. Time for new businesses and old businesses to change. Time to rethink the deal for employees, for contract workers, and for gig workers. Disruption creates the push to rethink the basic bargain for the workers who produced much of the value in this economy.

My message today is straightforward. Workers deserve a level playing field and some basic protections. No matter who they work for, where they work, or how the law classifies them. They deserve a strong safety net, dependable benefits, and the chance to bargain over their working conditions. That is the basic deal. And that’s the deal that is necessary to restore a strong and sustainable American middle class.

Most workers aren’t asking for the moon. They want to be able to take care of their families, to buy a home, send their kids to college, save a little money for retirement. They want some security. And they want to know their kids are going to have a chance to do better than they did. That’s the promise of America. But that promise won’t come true unless we make some real changes.

Workers have a right to expect our government to work for them. To set the basic rules of the game. If this country is to have a strong middle class, then we need the policies that will make that possible. That’s how shared prosperity has been built in the past, and that is our way forward now. Change won’t be easy. But we don’t get what we don’t fight for. And I believe that America’s workers are worth fighting for. Thank you all.

Further Reference

The Next Social Contract event home page.