Cory Doctorow: Thank you very much. Hi. So, there’s little formality first. As a member in good standing of the Order of After-Dinner and Conference Speakers of England and Wales, I am required as the last speaker before lunch to make a joke about being the last speaker before lunch. This is that joke. Thank you.

So, I work for Electronic Frontier Foundation. And I’ve met some of you in the halls here, and when I mention I work with EFF they say, “Oh you guys have been around for a long time.” And it’s true. Like not just Internet time. Not like “this is Zcash’s second birthday so we’re the doddering old men of cryptocurrency”-long time. Like, we’ve been around for a quarter century. A legitimate long time. And I want to talk about our origin story, about the key victories that we scored really early on, a quarter century ago, that really are the reason you guys and you folks are in this room today.

I want to talk about the Crypto Wars. Not those crypto wars.

These Crypto Wars.

So, back in the late 90s, the NSA classed cryptography as a munition and imposed strict limits on civilian access to strong crypto. And there were people as you heard Primavera speak about who called themselves cypherpunks, cryptoanarchists, who said that this was bad policy; it was a governmental overreach and it needed to be changed. And they tried a whole bunch of different tactics to try and convince the government that this policy was not good policy.

So, they talked about how it was ineffective, right. They said you can ban civilian access to strong cryptography and only allow access to weak crypto, the 50-bit version of DES, and that will not be sufficient to protect people. They made this as a technical argument. They said like, “Look, we believe that you could brute force DES with consumer equipment.” And the court said, “Well, who are we gonna believe, you or the NSA? Because the NSA, they hire all the PhD mathematicians that graduate from the Big 10 schools and they tell us that DES 50 is good enough for anyone. So why should we believe you?”

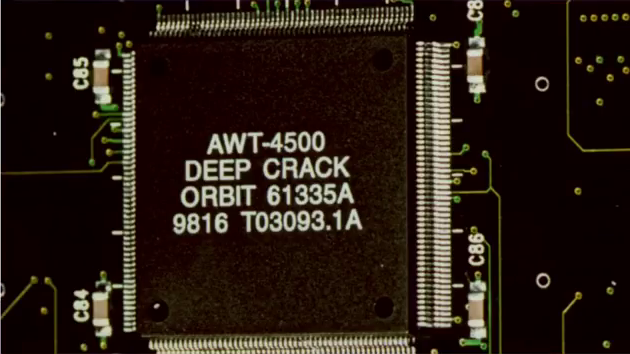

And so, we did this. We built this thing called the DES Cracker. It was a quarter-million-dollar specialized piece of equipment that could crack the entire key space of DES in two hours, right. So we said like, “Look. Here’s your technical proof. We can blow through the security that you’re proposing to lock down the entire US financial, political, legal, and personal systems with, for a quarter-million dollars.

And they said, “Well, maybe that’s true but we can’t afford to have the criminals go dark, right. They’re gonna hide behind crypto and we won’t be able to spy on them.”

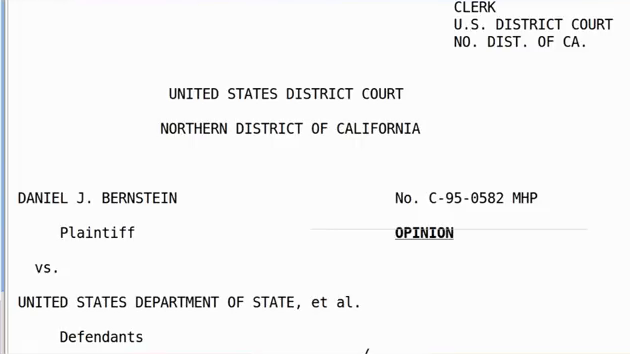

So in the face of all that resistance, we finally came up with a winning argument. We went to court on behalf of a guy named Daniel J. Bernstein. You probably heard of DJB. He’s a cryptographer. He’s a cryptographer whose name is all over all the ciphers you use now. But back then DJB was a grad student at the University of California at Berkeley. And he had written a cipher that was stronger than DES 50. And he was posting it to Usenet. And we went to the Ninth Circuit and we said, “We believe that the First Amendment of the US Constitution, which guarantees the right to free speech, protects DJB’s right to publish source code.” That code is a form of expressive speech as we understand expressive speech in the US Constitutional framework.

And this worked, right. Making technical arguments didn’t work. Making economic arguments didn’t work. Making law enforcement arguments didn’t work. Recourse to the Constitution worked. We won in the Ninth Circuit. We won at the Appellate Division. And the reason that you folks can do ciphers that are stronger than DES 50, which these days you can break with a Raspberry pi, the reason you can do that is because we won this case. [applause] Thank you.

So I’m not saying that to suck up to you, right. I’m saying that because it’s an important note in terms of tactical diversity in trying to achieve strategic goals. It turns out that making recourse to the Constitution is a really important tactical arrow to have in your quiver. And it’s not that the Constitution is perfect. And it’s certainly not true that the US always upholds the Constitution, right. All countries fall short of their goals. The goals that the US falls short of are better than the goals that many other countries fall short of. The US still falls short of those goals and the Constitution is not perfect.

And you folks, you might be more comfortable thinking about deploying math and code as your tactic, but I want to talk to you about the full suite of tactics that we use to effect change in the world. And this is a framework that we owe to this guy Lawrence Lessig. Larry is the founder of Creative Commons and has done a lot of other important stuff with cyber law and now works on corruption. That’s a connection I’m gonna come back to. And Larry says that there are four forces that regulate our world, four tactical avenues we can pursue.

There’s code: that’s what’s technically possible. Making things like Deep Crack.

There’s markets: what’s profitable. Founding businesses that create stakeholders for strong security turned out to be a really important piece to continuing to advance the crypto agenda because there were people who would show up and argue for more access to crypto not because they believed in the US Constitution but because their shareholders demanded that they do that as part of their ongoing funding.

There’s norms: what’s socially acceptable. Moving from the discussion of crypto as a thing that exists in the realm of math and policy, and to a thing that is part of what makes people good people in the world to convince them that for example allowing sensitive communications to go in the clear is a risk that you put not just on yourself but on the counter parties to your communication. I mean I think we will eventually arrive at a place where sending sensitive data in the clear will be the kind of technical equivalent of inviting people to a party where you close the door and chain smoke, right. It’s your selfish laziness putting them at risk.

And then, there’s law: what’s legal.

Now, the rule of law is absolutely essential to the creation and maintenance of good cipher systems. Because there is no keylength, there’s no cipher system, that puts you beyond the reach of law. You can’t audit every motherboard in every server in the cloud that you rely on for a little backdoor chip the size of a grain of rice that’s tapped right into the motherboard control system.

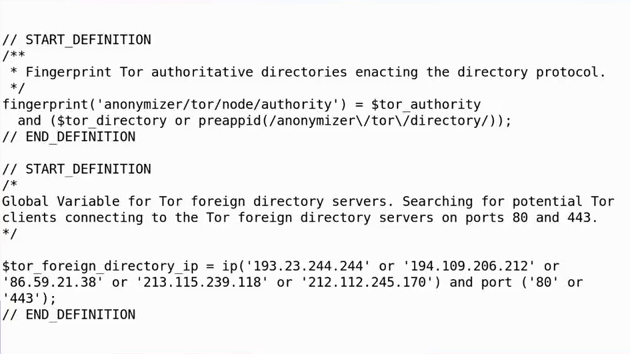

You can’t make all your friends adopt good operational security. This is a bit of the rules used by the deep packet inspection system deployed by the NSA. This was published in a German newspaper after it was leaked to them. The deep packet inspection rules that the NSA was using to decide who would get long-term retention of their communications and who wouldn’t, they involved looking for people who had ever searched for how to install Tor or Tails or Cubes. So if you had ever figured out how to keep a secret, the NSA then started storing everything you ever sent. In case you ever communicated with someone who wasn’t using crypto and through that conveyed some of the things that was happening inside your black box conversations. You can’t make everybody you will ever communicate with use good crypto. And so if the state is willing to exercise illegitimate authority, you will eventually be found out by them.

You can’t audit the ciphers that every piece of your toolchain uses, including pieces that you don’t control that are out of your hands and in the hands of third parties. One of the things we learned from the Snowden leaks was that the NSA had sabotaged the random number generator in a NIST standard in order to weaken it so that they could backdoor it and read it. And so long as the rule of law is not being obeyed, so long as you have spy agencies that are unaccountably running around sabotaging crypto standards that we have every reason to believe otherwise are solid and sound, you can never achieve real security. This turns out to be part of a much larger thing called Bullrun in the US and Edgehill in the UK that the NSA and MI5 were jointly doing to sabotage the entire crypto toolchain from hardware to software to standards to random number generators.

Opsec is not going to save you. Because security favors attackers. If you want to be secure from a state, you have to be perfect. You don’t just have to be perfect when you’re writing code and checking it in. You have to be perfect all the time. You have to never make a single mistake. Not when you’re at a conference that you traveled across the ocean to when you’re horribly jet lagged. Not when your baby has woken you up at three in the morning. Not when you’re a little bit drunk—you have to make zero mistakes.

In order for the state to penetrate your operational security, they have to find one mistake that you’ve made. And they get to cycle a new shift in every eight hours to watch you. They get to have someone spell off the person who’s starting to get screen burn-in on their eyes and has to invert the screen because they can no longer focus on the letters. They just send someone else to sit down at that console and watch you. So your operational security is not going to save you. Over time the probability that you will make a mistake approaches one.

So crypto is not a tool that you can use to build a parallel world of code that immunizes you from an illegitimate, powerful state. Superior technology does not make inferior laws irrelevant.

But technology, and in particular privacy and cryptographic technology, they’re not useless. Just because your opsec won’t protect you forever doesn’t mean that it won’t protect you for just long enough. Crypto and privacy tools, they can open a space in which, for a limited time, before you make that first mistake, you can be sheltered from that all-seeing eye. And in that space, you can have discussions that you’re not ready to have in public yet. Not just discussions where you reveal that your employer has been spying on everyone in the world, but all of the discussions that have brought us to where we are today. You know, it’s remarkable to think that within our lifetimes, within living memory, it was illegal in much of the world to be gay. And now in most of those territories gay people can get married. It was illegal to smoke marijuana and now in the country I’m from, Canada, marijuana is legal, right, in every province of the country. It was illegal to practice so-called interracial marriage. There are people who are the products of those marriages, who were illegal.

So how in our lifetimes did we go from these regimes where these activities were prohibited, to ones in which they are embraced and considered normal? Well it was because people who had a secret that they weren’t ready to talk about in public yet could have a space that was semi-public. Where they could choose their allies. They could find people who they thought they could trust with a secret. And they could whisper the true nature of their hearts to them. And they could recruit them into an ever-growing alliance of people who would stand up for them and their principles. They could whisper the love that dare not speak its name until they were ready to shout it from the hills.

And that’s how we got here. If we eliminate privacy and cryptography, if we eliminate the ability to have these semi-public conversations, we won’t arrive at a place in which social progress continues anyway. We’ll arrive at a place that will be much like the hundreds of years that preceded the legalization of these activities that are now considered normal. Where people that you love went to their graves with secrets in their hearts that they never confessed to you. Great aches that you had unknowingly contributed to, because you never knew their true selves.

So we need good tech policy, and we’re not getting it. In fact we’re getting bad technology policy that’s getting worse by the day.

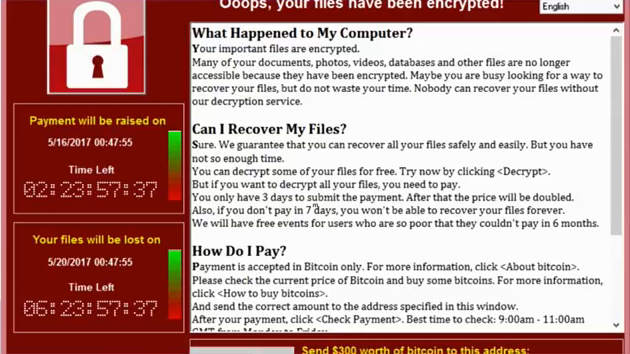

So, you may remember that over the last two years we discovered that hospitals are computers that we put sick people into. And when we take the computers out of the hospitals, they cease to be places where you can treat sick people. And that’s because of an epidemic of ransomware. There’s been a lot of focus on the bad IT policies of the hospitals. And the hospitals had some bad IT policies. You shouldn’t be running Windows XP, there’s no excuse for it and so on.

But, ransomware had been around for a long time and it hadn’t taken down hospitals all over the world. The way that ransomware ended up taking down hospitals all over the world is somebody took some off-the-shelf ransomware and married it to a thing called Deep Blue. Or EternalBlue, rather. And EternalBlue was an NSA exploit. They had discovered a vulnerability in Windows XP, and rather than taking it to Microsoft and saying, “You guys had better patch this because it’s a really bad zero-day,” they had just kept it secret, in their back pocket, against the day that they had an adversary they wanted to use it against.

Except before that could happen, someone leaked their cyber weapon. And then dumdums took the cyber weapon and married it to this old piece of ransomware and started to steal hospitals. Now, why do I call these people dumdums? Because the ransom they were asking for was $300. They didn’t even know that they’d stolen hospitals. They’re just opportunistically stealing anything that was connected to an XP box and then asking for $300, in cryptocurrency, in order to unlock it.

So, this is not good technology policy. The NSA believes in a doctrine called NOBUS: “No One But US is smart enough to discover this exploit.” Now, first of all we know that’s not true. We know that the NSA… From the Crypto Wars, we know that the NSA does not have a monopoly on smart mathematicians, right. These were the people who said DES 50 was strong enough for anyone. They were wrong about that, they’re wrong about this. But even if you believe that the NSA would never…that the exploits that they discovered would never be independently rediscovered, it’s pretty obvious that that doesn’t mean that they won’t be leaked. And once they’re leaked, you can never get that toothpaste back in the tube.

Now, since the Enlightenment, for 500 years now, we’ve understood what good knowledge creation and technology policy looks like. So let me give you a little history lesson. Before the Enlightenment, we had a thing that looks a lot like science through which we did knowledge creation. It was called alchemy. And what alchemists did is a lot like scientists. You observe two phenomena in the universe. You hypothesize a causal relationship, this is making that happen. You design an experiment to test your causal relationship. You write down what you think you’ve learned.

And here’s where science and alchemy part ways. Because alchemists don’t tell people what they think they’ve learned. And so they are able to kid themselves that the reason that their results seem a little off is because maybe they made a little mistake when they were writing them down and not because their hypothesis was wrong. Which is how every alchemist discovers for himself the hardest way possible that you should not drink mercury, right.

So for 500 years, alchemy produces no dividends. And then alchemists do something that is legitimately miraculous. They convert the base metal of superstition into the precious metal of knowledge, by publishing. By telling other people what they know. Not just their friends who’ll go easy on them but their enemies, right, who if they can’t find a single mistake in their work, they know that their work is good. And so, as a first principle whenever you’re doing something important everyone should be able to criticize it. Otherwise you never know that it works. So you would hope that that’s how we would operate in the information security realm. But that’s not how we’re operating.

In 1998 Congress passed this law, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. They then went to the European Union in 2001 and arm-twisted them into passing the European Union Copyright Directive. And both of these laws have a rule in them that says that you’re not allowed to break digital rights management. You’re not allowed to bypass a system that restricts access to a copyrighted work.

And in the early days, this was primarily used to stop people from making region-free DVD players. But now, everything’s got a copyrighted work in it, because everything’s got a system on a chip in it that costs twenty-two cents and has 50,000 lines of code including the entire Linux kernel and usually an instance of BusyBox running with the default root password of “admin/admin”.

And because that’s a copyrighted work, anyone who manufactures a device where they could make more money if they could prescribe how you use that device, can just add a one-molecule-thick layer of DRM in front of that copyrighted work. And then because in order to reconfigure the device you have to remove the DRM, they can make removing DRM and thus using your own property in ways that benefit you into a felony punishable by a five-year prison sentence and a $500 thousand fine.

And so there’s this enormous temptation to add DRM to everything and we’re seeing it and everything. Pacemakers, voting machines, car engine parts, tractors, implanted defibrillators, hearing aids. There’s a new closed-loop artificial pancreas from Johnson & Johnson…it’s a continuous glucose monitor married to an insulin pump with some machine learning intelligence to figure out what dose you need from moment to moment. And it uses proprietary insulin cartridges that have a layer of DRM in them to make sure that to stay alive you only feed your internal organ the material that the manufacturer has approved, so that they can charge you an extreme markup.

So that’s bad. That’s the reason we’re seeing DRM everywhere. But the effect of that is what it does to security research. Because under this rule, merely disclosing defects in security that might help people bypass DRM also exposes you to legal jeopardy. So this is where it starts to get scary, because as microcontrollers are permeating everything we use, as hospitals are turning into computers we put sick people into, we are making it harder for critics of those devices to explain the dumb mistakes that the people who made them have made. We’re all drinking mercury.

And this is going everywhere. Particularly, it’s going into your browser. So, several years ago the W3C was approached by Netflix and a few of the other big entertainment companies to add DRM to HTML5 because it was no longer technically simple to DRM in browsers because of the way they were changing the APIs. And the W3C said that they would do it. And there’s a—it’s a long, complicated story why they went into it. But I personally and EFF, we had a lot of very spirited discussions with the W3C leadership over this. And we warned them that we thought that the companies that wanted to add DRM to their browsers didn’t want to just protect their copyright. We thought that they would use this to stop people from disclosing defects in browsers. Because they wanted to be able to not just control their copyright but ensure that there wasn’t a way to get around this copyright control system.

And they said, “Oh no, never. These companies are good actors. We know them. They pay the membership dues. They would never abuse this process to come after security researchers who were making good faith, honest, responsible disclosures,” whatever; you add your adjective for a disclosure that’s made in a way that doesn’t make you sad, right. There are all these different ways of talking about security disclosures.

And we said alright, let’s find out. Let’s make membership in the W3C and participation in this DRM committee contingent on promising only to use the DMCA to attack people who infringe copyright, and never to attack people who make security disclosures. And the entire cryptocurrency community and blockchain community who were in the W3C working groups, they backed us on this. In fact it was the most controversial standards vote in W3C history. It was the only one that ever went to a vote. It was the only one that was ever appealed. It was the only one that was ever published without unanimous support. It was published with 58% support, and not one of the major browser vendors, not one of the big entertainment companies, signed on to a promise not to sue security researchers who revealed defects in browsers.

So let’s talk a little about security economics and browsers. So security, obviously it’s not a binary, it’s a continuum. We want to be secure from some attack. You heard someone talk about threat modeling earlier. So like, you’ve got a bank vault. You know that given enough time and a plasma torch, your adversary can cut through that bank vault. But you don’t worry about that because your bank vault is not meant to secure your money forever, it’s meant to secure your money until a security guard walks by on their patrol and calls the police, right. Your bank vault is integrated with the rule of law. It is a technical countermeasure that is backstopped by the rule of law. And without the rule of law, your bank vault will eventually be cut open by someone with a plasma cutter.

So, security economics means factoring in the expected return on a breach into the design of the system. If you have a system that’s protecting $500 in assets, you want to make sure that it will cost at least $501 to defeat it. And you assume that you have a rational actor on the other side who’s not going to come out of your breach one dollar in the hole. You assume that they’re not going to be dumdums.

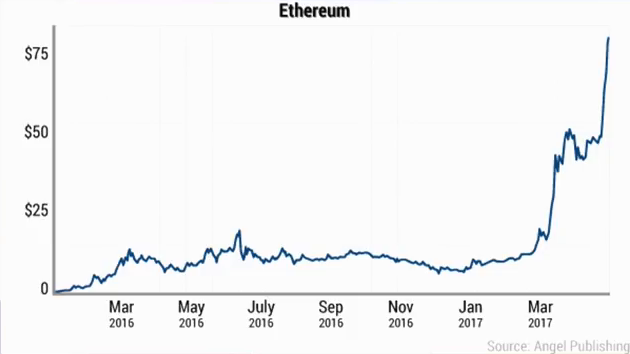

So, there’s a way that this frequently goes wrong, a way that you get context shifts that change the security economics calculus. And that’s when the value of the thing that you’re protecting suddenly goes up a lot and the security measures that you’re using to protect it don’t. And all of a sudden your $501 security isn’t protecting $500 worth of stuff. It turns out that it’s protecting $5 million worth of stuff. And the next thing you know there’s some dude with a plasma cutter hanging around your vault.

So this challenge is especially keen in the realm of information security because information security is tied to computers, and computers are everywhere. And because computers are becoming integrated into every facet of our life faster than we can even keep track of it, every day there’s a new value that can be realized by an attacker who finds a defect in computers that can be widely exploited. And so every day the cost that you should be spending to secure your computers is going up. And we’re not keeping up. In fact, computers on average are becoming less secure because the value that you get when you attack computers is becoming higher, and so the expected adversary behavior is getting better resourced and more dedicated.

So this is where cryptocurrency does in fact start to come into the story. It used to be that if you found a defect in widely-used consumer computing hardware, you could expect to realize a few hundred or at best a few thousand dollars. But in a world where intrinsically hard-to-secure computers are being asked to protect exponentially-growing cryptocurrency pools…well you know how that works, right? You’ve seen cryptojacking attacks. You’ve seen all the exchanges go down. You understand what happens when the value of the asset being protected shoots up very suddenly. It becomes extremely hard to protect.

So, you would expect that in that world, where everything we do is being protected by computers that are intrinsically hard to protect and where we need to keep adding more resource to protect them, that states would take as their watchword making crypto as easy to implement as possible; making security as easy as possible to achieve. But, the reverse is happening. Instead what’s happening is states are starting to insist that we’re gonna have to sacrifice some of our security to achieve other policy goals.

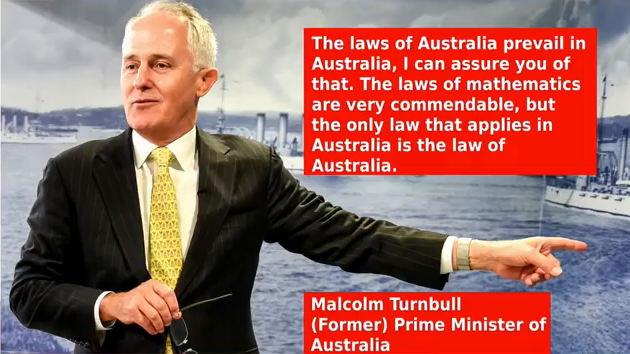

So this guy used to be Prime Minister of Australia, he’s not anymore. Wait six months, the current Prime Minister of Australia will also not be Prime Minister of Australia anymore. This guy, Malcolm Turnbull… Sorry, did I just get his name wrong? I just blew up his name. What is his name? God, he went so quickly. Malcolm Turnbull, it is Malcolm Turnbull, it’s right there on the slide. I almost called Malcolm Gladwell.

So he gave this speech where he was explaining why he was going to make it the law that everybody had to backdoor their crypto for him. And you know, all these cryptographers had shown up and they said, “Well the laws of math say that we can’t do that. We can’t make you a thing that’s secure enough to protect the government and its secrets, but insecure enough that the government can break into it.”

And he said…I’m not gonna do the accent. He said, “The laws of Australia prevail in Australia. I can assure you of that. The laws of mathematics are very commendable, but the only law that applies in Australia is,” read it with me, “the law of Australia.” I mean… This may be the stupidest technology thing ever said in the history of really dumb technology utterances.

But he almost got there. And he’s not alone, right. The FBI has joinedhim in this call. You know, Canada’s joined him in this call. Like, if you ever needed proof that merely having good pecs and good hair doesn’t qualify you to have good technology policy the government of Justin Trudeau and its technology policy has demonstrated this forever. This is an equal opportunity madness that every developed state in the world is at least dabbling in.

And we have ended up not just in a world where fighting crime means eliminating good security. I mean it’s dumber than that, right. We’ve ended up in a world where making sure people watch TV the right way means sacrificing on security.

Now, the European Union, they just actually had a chance to fix this. Because that copyright directive that the US forced them to pass in 2001 that has the stupid rule in it that they borrowed from the DMCA, it just came up for its first major revision in seventeen years. The new copyright directive is currently nearly finalized; it’s in its very last stage. And rather than fixing this glaring problem with security in the 21st century, what they did was they added this thing called Article 13.

So Article 13 is a rule that says if you operate a platform where people can convey a copyrighted work to the public… So like if you have a code repository, or if you have Twitter, or if you have YouTube, or if you have SoundCloud, or if you have any other way that people can make a copyrighted work available. If you host Minecraft skins, you are required to operate a crowdsourced database of all the copyrighted works that people care to add to it and claim; so anyone can upload anything to it and say, “This copyright belongs to me.” And if a user tries to post something that appears in the database, you are obliged by law to censor it. And there are no penalties for adding things to the database that don’t belong to you. You don’t even have to affirmatively identify yourself. And, the companies are not allowed to strike you off from that database of allegedly copyrighted works, even if they repeatedly catch you chaffing the database with garbage that doesn’t belong to you—the works of William Shakespeare, all of Wikipedia, the source code for some key piece of blockchain infrastructure which now can’t be posted to a WordPress blog and discussed until someone at Automattic takes their tweezers and goes to the database and pulls out these garbage entries, whereupon a bot can reinsert them into the database one nanosecond later.

So this is what they did, instead of fixing anti-circumvention rules to make the Internet safe for security. So, I mention this is in it’s very last phase of discussion, and it looked like it was a fix and then the Italian government changed over and they flipped positions. And we’re actually maybe going to get to kill this, but only if you help. If you’re a European, please go to saveyourinternet.eu and sent a letter to your MEPs. This is really important. Because this won’t be fixed for another seventeen years if this passes; saveyourinternet.eu.

So, when we ask ourselves why are governments so incapable of making good technology policy, the standard account says it’s just too complicated for them to understand, right. How could we expect these old, decrepit, irrelevant white dudes to ever figure out how the Internet works, right? If it’s too technological you’re too old, right?

But sorting out complicated technical questions, that’s what governments do. I mean, I work on the Internet and so I think it’s more complicated than other people’s stuff. But you know, when I’m being really rigorously honest? I have to admit that it’s not more complicated than public health, or sanitation, or building roads. And you know, we don’t build roads in a way that is as stupid as we have built the Internet.

And that’s because the Internet is much more hotly contested. Because every realm of endeavor intersects with the Internet, and so there are lots of powerful interests engaged in trying to tilt Internet policy to their advantage. The TV executives and media executives who pushed for Article 13 you know, they’re not doing it because they’re mustache-twirling villains. They’re just doing it because they want to line their pockets and they don’t care what costs that imposes on the rest of us. Bad tech policy, it’s not bad because making good policy is hard. It’s bad because making bad policy has a business model.

Now, tech did not cause the corruption that distorts our policy outcomes. But it is being supercharged by the same phenomenon that is distorting our policy outcomes. And that’s what happened with Ronald Reagan, and Margaret Thatcher, and their cohort who came to power the same year the Apple II Plus shipped. And among the first things they did in office was dismantle our antitrust protections, and allowed companies to do all kinds of things that would have been a radioactively illegal in the decades previous. Like buying all their competitors. Like engaging in illegal tying. Like using long-term contracts in their supply chain to force their competitors out. Like doing any one of a host of things that might have landed them in front of an antitrust regulator and broken up into smaller pieces the way AT&T had been.

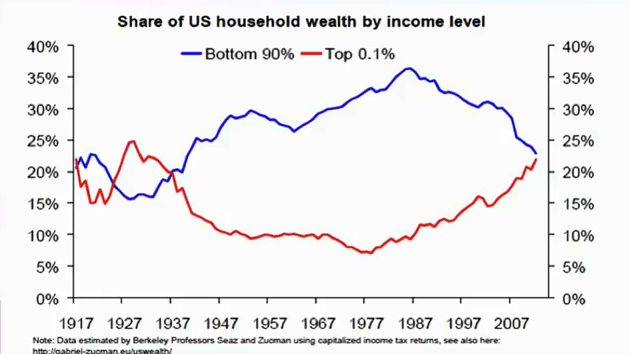

And as that happened, we ended up in a period in which inequality mounted and mounted and mounted. And forty years later, we’ve never lived in a more unequal world. We have surpassed the state of inequality of 18th century France, which for many years was the gold standard for just how unequal a society can get before people start chopping off other people’s heads.

And unequal states are not well-regulated ones. Unequal states are states in which the peccadillos, cherished illusions, and personal priorities of a small number of rich people who are no smarter than us start to take on outsized policy dimensions. Where the preferences and whims of a few plutocrats become law. [applause]

In a plutocracy, policy only gets to be evidence-based when it doesn’t piss off a rich person. And we cannot afford distorted technology policy. We are at a breaking point. Our security and our privacy and our centralization debt is approaching rupture. We are about to default on all of those debts, and we won’t like what the bankruptcy looks like when that arrives.

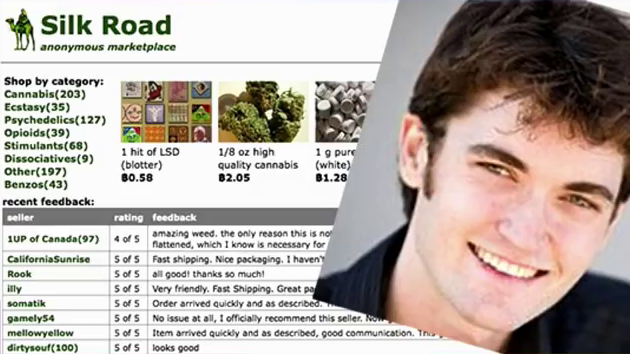

Which brings me back to cryptocurrency and the bubble that’s going on around us. The bubbles, they’re not fueled by people who have an ethical interest in decentralization or who worry about overreaching state power. Those bubbles, right, all the frothy money that’s in there. Not the coders who are writing it or the principled people who think about it but all the money that’s just sloshing through it and making your tokens so volatile that the security economics are impossible. That money is being driven by looters, who are firmly entrenched in authoritarian states. The same authoritarian states that people are interested in decentralization say we want to get rid of. They’re the ones who are buying cyber weapons to help them spy on their own populations to figure out who is fermenting revolutions so they can round them up and torture them and arrest them. So that they can be left to loot their national treasuries in peace and spin the money out through financial secrecy havens like the ones that we learned about in the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers.

And abetting the oligarchic accumulation of wealth, that is not gonna create the kinds of states that produce the sound policy that we need to make our browsers secure. It will produce states whose policy is a funhouse mirror reflection of the worst ideas of the sociopaths who have looted their national wealth and installed themselves as modern feudal lords.

Your cryptography will not save you from those states. They will have the power of coercive force and the unblinking eye of 24/7 surveillance contractors. The Internet, the universal network where universal computing endpoints can send and receive cryptographically secure messages is not a tool that will save us from coercive states, but it is a tool that will give us a temporary shelter within them. A space that even the most totalitarian of regimes will not be able to immediately penetrate. Where reformers and revolutionaries can organize, mobilize, and fight back. Where we can demand free, fair, and open societies with broadly-shared prosperity across enough hands that we can arrive at consensuses that reflect best evidence and not the whims of a few. Where power is decentralized.

And incidentally, having good responsive states will not just produce good policy when it comes to crypto. All of our policy failures can be attributed to a small, moneyed group of people who wield outsize power to make their bottom line more important than our shared prosperity. Whether that’s the people who spent years expensively sowing doubt about whether or not cigarettes would give us cancer, or the people who today are assuring us that the existential threat that the human species is facing is a conspiracy among climate scientists who are only in it for the money.

So you’re here because you write code. And you may not be interested in politics, but politics is interested in you. The rule of law needs to be your alpha and omega. Because after all, all the Constitution is a form of consensus, right. It’s the original consensus-seeking mechanism. Using the rule of law to defend your technology, it’s the most Internet thing in the world. Let’s go back to Bernstein. When we went to Bernstein and argued this case, we essentially went on an Internet message board and made better arguments than the other people. And we convinced the people who were listening that our arguments were right. This is how you folks resolve all of your problems, right? Proof of concept. Running code. Good arguments. And you win the battle of the day.

So making change with words? That’s what everybody does, whether we’re writing code or writing law. And I’m not saying you guys need to stop writing code. But you really need to apply yourself to the legal dimension, too. Thank you.

Cory Doctorow: So, we’re gonna ask some questions now. I like to call alternately on people who identify as women or non-binary and people who identify as male or non-binary, and we can wait a moment if there’s a woman or non-binary person wants to come forward first. There’s a mic down there and then there’s a rover with a mic. Just stick up your hand.

Audience 1: As someone who spent a lot time involved in the Internet, I’m sure you’ve read the book The Sovereign Individual. And I recently read this book and it talked a lot about how the Internet would increase the sovereignty of individuals and also how cryptocurrencies will. And it predicted a massive increase in inequality as a direct result of the Internet. Could you comment on that?

Doctorow: Yeah I haven’t read the book so I’m not gonna comment directly on the book. But I think it’s true that if you view yourself as separate from the destinies of the people around you that it will produce inequality. I think that that’s like, empirically wrong, right. Like, if there’s one thing we’ve learned about the limits of individual sovereignty it’s that you know, you have a shared microbial destiny. You know, I speak as a person who left London in the midst of a measles epidemic and landed in California right after they stamped it out by telling people that you had to vaccinate your kids or they couldn’t come to school anymore.

We do have shared destinies. We don’t have individual sovereignty. And even if you’re the greatest and— You know, anyone who’s ever run a business knows this, right. You could have a coder who’s a 100X coder, who produces 100 times more lines of code than everybody else in the business. But if that coder can’t maintain the product on their own, and if they’re colossal asshole that no one else can work with? Then that coder is a liability not an asset, right. Because you need to be able to work with more than one person in order to attain superhuman objectives. Which is to say more than one person can do. And everything interesting is superhuman, right. The limits on what an individual can do are pretty strong.

And so yeah, I think that that’s true. I think that the kind of policy bent toward selfishness kind of self-evidently produces more selfish outcomes. But not better ones, right. Not ones that reflect kind of a shared prosperity and growth. Thank you.

Hi.

Audience 2: Hi. I have had the pleasure of seeing you keynote both Decentralized Web Summits, and the ideas you bring to these talks always really stay with me longer than anything else.

Doctorow: Thank you.

Audience 2: With what you’ve talked about here, this is honestly one of the most intimidating and terrifying topics, and I’m wondering what are some ways besides staying informed and trying not to get burned out by it all, what are some ways that people can make a difference?

Doctorow: So, I recently moved back from London to California, as I mentioned. And one of the things that that means is I have to drive now, and I’m a really shitty driver. And in particular I’m a really shitty parker. So when I have to park, [miming wild steering motions:] I do a lot of this, and then lot of this, and then a lot of this, and a lot of this. And what I’m doing is I’m like…moving as far as I can to gain one inch of available space. And then—or centimeter. And then moving into that centimeter of available space, because that opens up a new space that I can move into. And then I move as far as I can and I open up a new space.

We do this in computing all the time, right. We call it hill-climbing. We don’t know how to get from A to Zed. But we do know how to get from A to B, right. We know where the higher point of whatever it is we’re seeking is—stability or density or interestingness or whatever. And so we move one step towards our objective. And from there we get a new vantage point. And it exposes new avenues of freedom that we can take. I don’t know how we get from A to Zed. I don’t know how we get to a better world. And I actually believe that because the first casualty of every battle is the plan of attack, that by the time we’ve figured out the terrain, that it would have been obliterated by the adversaries who don’t want us to go there.

And so, instead, I think we need heuristics. And that heuristic is to see where your freedom of motion is at any moment and take it. Now, Larry Lessig he’s got this framework, the four forces: code, law, norms, and markets. My guess is that most of the people in this room are doing a lot with norms and and markets, right. That’s kind of where this conference sits in that little two-by-two. And as a result you may be blind to some of the law and norm issues that are available to you. That it might be that jumping on EFF’s mailing list, or if you’re a European getting on the EDRi mailing list. Or the mailing list for the individual digital rights groups in your own countries like Netzpolitik in Germany, or the Quadrature du Net in France, or Open Rights Group in the UK, or Bits of Freedom in the Netherlands and so on.

Getting on those lists and at the right moment calling your MEP, calling your MP, or even better yet like, actually going down when they’re holding surgeries, when they’re holding constituency meetings. They don’t hear from a lot of people who are technologically clued-in. Like, they only get the other side of this. And you know, I’ve been in a lot of these policy forums, and oftentimes the way that the other side prevails is just by making it up, right. Like one of the things we saw in this filter debate like, we had computer scientists who were telling MEPs… You know, the seventy most eminent computer scientists in the world, right, a bunch of Turing Prize winners. Vint Cerf and Tim Berners-Lee said like, “These filters don’t exist and we don’t know how to make ’em.” And they were like, “Oh, we’ve got these other experts who say ‘we know how to do it.’ ” And they had been told for years that the only reason nerds hadn’t built those filters is they weren’t nerding hard enough, right.

And if they actually hear from their own constituents, people who run small business that are part of this big frothy industry that everybody wants, their national economies to participate in. Who show up at their lawmakers’ offices and say, “This really is catastrophic. It’s catastrophic to my business. It’s catastrophic to the Internet,” they listen to that. It moves the needle.

And you know, you heard earlier someone say are we at pitch now? Well, I should pitch, right? I work for Electronic Frontier Foundation. We’re a nonprofit. The majority of our money comes from individual donors. It’s why we can pursue issues that are not necessarily on the radar of the big foundations or big corporate donors. We’re not beholden to anyone. And it’s people like you, right, who keep us in business. And I don’t draw money from EFF. I’m an MIT Media Lab research affiliate and they give EFF a grant that pays for my work. So the money you give to EFF doesn’t land in my pocket. But I’ve been involved with them now for fifteen years and I’ve never seen an organization squeeze a dollar more. So, really think it’s worth your while; eff.org. Thank you.

Oh. Someone over here. Yes, hi.

Audience 3: Thank you very much. Really appreciate the speech. It was very inspiring.

Doctorow: Thank you.

Audience 3: Um, I think…maybe not sure how many other people feel this way, but one thing that’s been hard to me about politics in general, especially in the age of social media is, you know…there’s a lot of it that spreads messages of fear and anger and hatred. And sometimes it feels like when you want to say something and you want to spread a certain voice or just spread a certain message, that there’s this fear of getting swept up in all these messages and ideas and things that aren’t necessarily… You’re not necessarily aware of your own biases and things like that. How does one stay sane, and fight for you know, the right fight?

Doctorow: God. I you know, I wish I knew. I like— I’ll freely admit to you I’ve had more sleepless nights in the last two years than in all the years before it. I mean, even during the movement to end nuclear proliferation that I was a big part of in the 80s when I thought we were all going to die in a mushroom cloud, I wasn’t as worried as I am now. It’s tough.

I mean, for me like just in terms of like, personal…psychological opsec? I’ve turned off everything that non-consensually shoves Donald Trump headlines into my eyeballs? You know, that we talk a lot about how like, engagement metrics distort the way applications are designed. But you know, I really came to understand that that was happening about a year and a half ago. So for example they changed the default Android search bar? so that when you tapped in it it showed you trending…searches. Well, like, nobody has ever gone to a search engine to find out what other people are searching for, right? And the trending searches were inevitably “Trump threatens nuclear armageddon.” So the last thing I would do before walking my daughter to school every morning is I would go to the weather app. And I would tap in it to see the weather. And it’s weather and headlines. And the only headlines you can’t turn off are top headlines, and they’re trend—you know, they’re all “Trump Threatens Nuclear Armageddon,” right?

So I realized after a month of this that what had been really the most calming, grounding fifteen minutes of my day where I would walk with my daughter to school, and we’d talked about stuff and it was really quiet—we live on a leafy street… I’d just spend that whole time worrying about dying, right?

And so, I had to figure out how to like go through and turn all that stuff off. Now what I do is I block out times to think about headlines. So I go and I look at the news for a couple hours every day…and I write about it. I write Boing Boing, right. I write a blog about it. Not necessarily because my opinions are such great opinions. But because being synthetic and thoughtful about it means that it’s not just…buffeting me, right? It becomes a reflective rather than a reflexive exercise.

But I don’t know, right? I mean, I think that— And I don’t think it’s just the tech. I think we are living in a moment of great psychic trauma. We are living in a— You know. The reason the IPCC report was terrifying was not because of the shrill headlines. The IPCC report was terrifying because it is objectively terrifying, right.

And so, how do you make things that’re… I don’t know how you make things that’re objectively terrifying not terrifying. I think the best we can hope for is to operate, while we are terrified, with as much calm and aplomb and thoughtfulness as is possible.

How are we for time, do you want me off? I know my clock’s run out. Or can I take one more question? Stage manager? One more or… One more. Alright. And then we’ll ring us off.

Audience 4: Yeahhh!. Hi.

Doctorow: Better be good, though.

Audience 4: Okay, I’m ready. I work for the Media Lab, too. So, my question Cory—thank you for your talk. I think a lot of people in the cryptocurrency world think about the current systems that we exist in. And we’re trying to exit those systems to some extent and create parallel…financial, you know, political institutions, what have you, versus expressing voice within the current system. How do you balance exit versus voice in the current system?

Doctorow: Well… You know, in a technol— And I said before that like, a Constitutional argument is just an Internet flame war by another means, right? So, when you’re arguing about a commit and a pull request, one of the things you do is you do proof of concept, right? You show that the thing that you’re patching is real and can be exploited. Or you show that you you’ve unit tests to show that your patch performs well.

Those parallel exercises are useful as proof of concepts and as unit tests, right? They’re prototypes that we can fold back into a wider world. And I think that… The thing I worry about is not that technologists will build technology. I want technologists to build technology. It’s that they will think that the job stops when you’ve built the proof of concept. That’s where the job starts, right? When you can prove that you’ve written a better algorithm, you then have to convince the other stakeholders in the project that it’s worth the actual like non-zero cost of patching to make that work, right? Of going through the whole source tree and finding all the dependencies on the things that you’re pulling out and gracefully replacing them. Because you know, when you run a big data center you can’t just start patching stuff…you’ve got a toolchain that you have to preserve, right?

And so that’s where the job starts, right? Build your proof of concept, build us a parallel financial system, build us a whatever…so that we can figure out how to integrate it into a much wider, more pluralistic world. Not so that we can separate and seastead on our little…you know, world over there. Like, it doesn’t matter how great your— [applause] Thank you. Doesn’t matter how great your bunker is, right? Like you can’t shoot germs, right? Like if your solution allows the rest of the world to fall into chaos, and no one’s taking care of the sanitation system, you will still shit yourself to death of cholera, in your bunker, because like, you can’t shoot germs, right? So we need pluralistic solutions that work for all of us.

Audience 4: Thank you.

Doctorow: Thank you.

Alright. Thanks everyone.