Maurice Cherry: Where are the black designers? This is a presentation which was originally given at South by Southwest Interactive on March 15, 2015. Let’s go ahead and get started. As you are listening to this presentation, please use the hashtags #WATBD and #AIGATogether to continue this conversation online.

Now a brief intro. My name is Maurice Cherry. I’m from Selma, Alabama—yes, that Selma. This is my old high school. Doesn’t look like this anymore, they tore it down, now it looks like this:

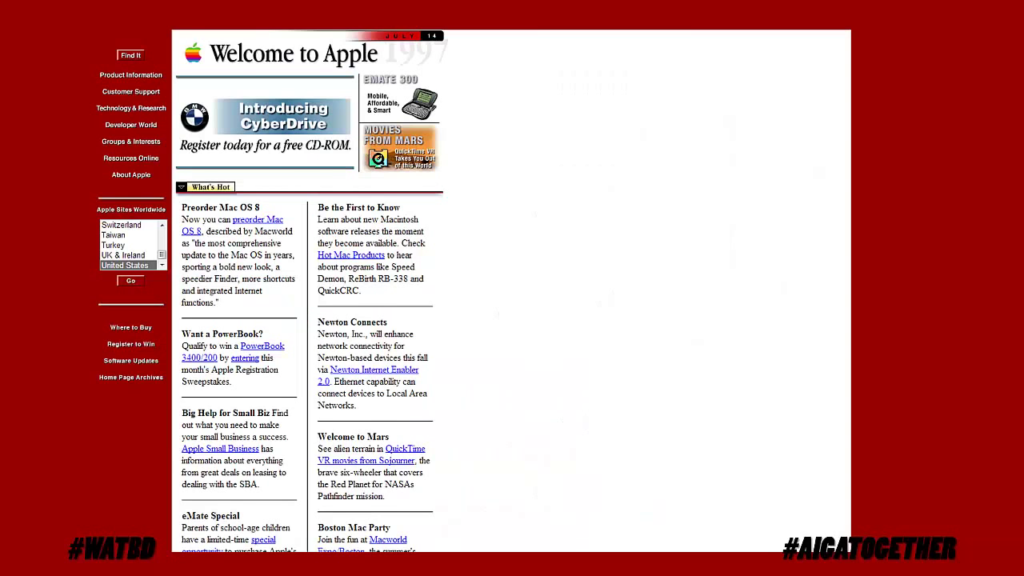

In 1996 I decided I really wanted to learn more about the Web. I had computers at home as a kid. I was really interested in learning about programming and design and wanted to know more about it. Because the Web as we knew it back then was just…bad. I mean, it was bad. It looked like this:

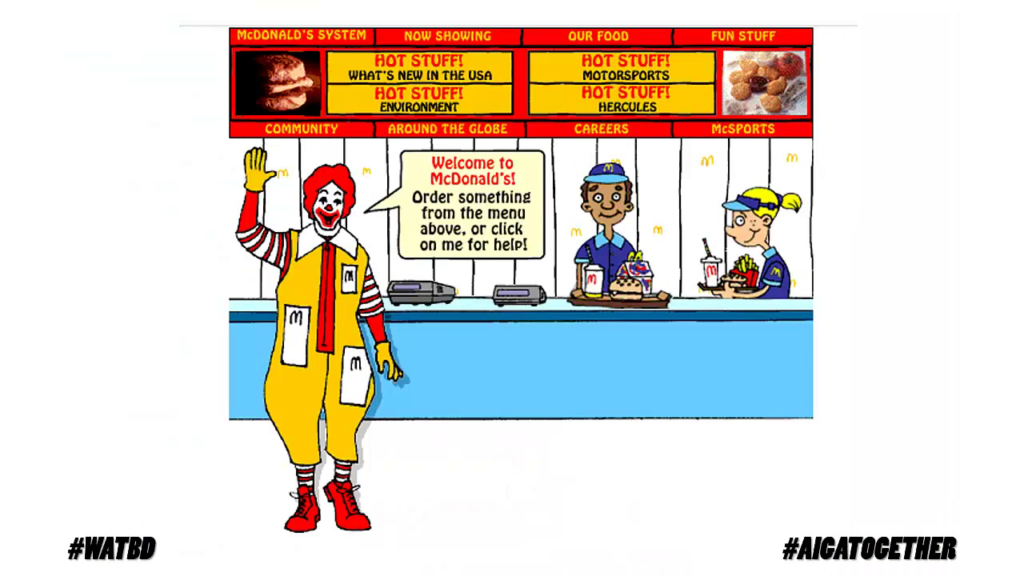

And it looked like this:

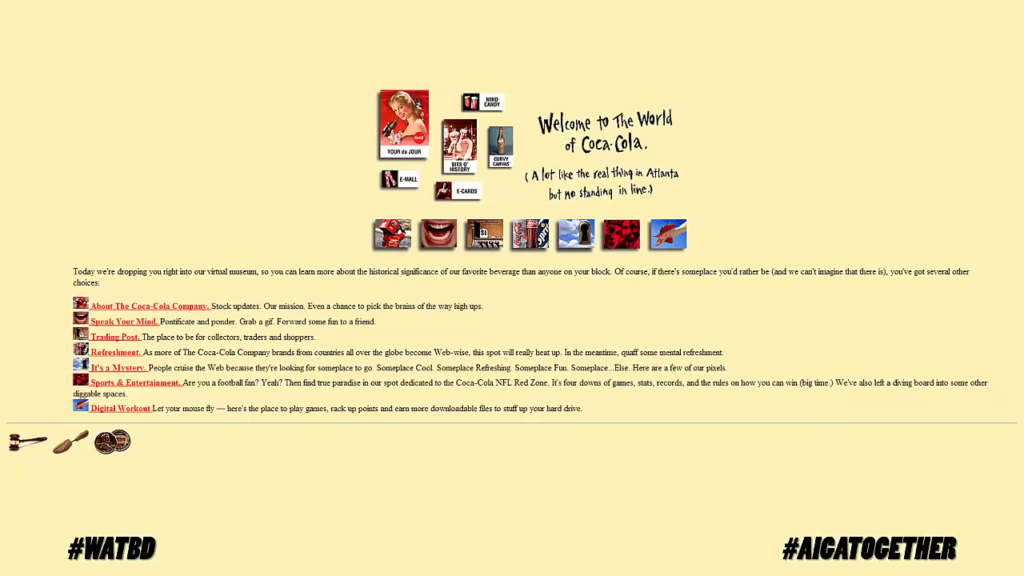

And it looked like this:

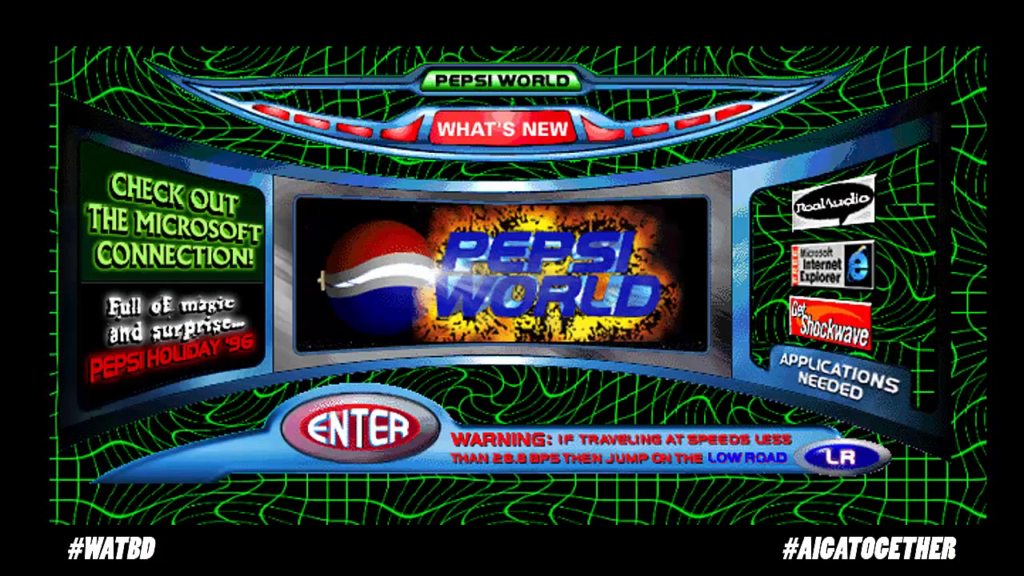

And it also looked like this with these cool little green Matrix swirls before The Matrix was here:

I graduated high school in 1999, decided I would go to Morehouse College. Because I wanted to major in computer science and computer engineering because I wanted to be like this guy:

This guy is Dwayne Wayne who was a character on a popular NBC sitcom at the time called A Different World. But as I started going through my coursework and everything, I found that I still wanted to learn about HTML. I still wanted to be a Web designer. And so when I went to my mentor and I told him about this he sort of hit me with one of these:

Told me that I should probably change my major because if you’re looking to do that now, we don’t offer that. So I changed my major to math, ended up getting my degree. Since then I have worked for some of these places and organizations in Atlanta.

In 2008 I started my own company called 318 Media, where I do WordPress design, MailChimp templates, things of that nature. I also teach. Here are some of the places where I teach, have taught, and will be teaching in the future.

Here are some of the big projects that I’ve done so far, The Black Weblog Awards, The Year of Tea, Revision Path, 28 Days of the Web. I’ll talk about those last two in a little bit.

Here’s some of the places that my work has been featured as well.

So let’s get to the meat of the presentation, where are the black designers?

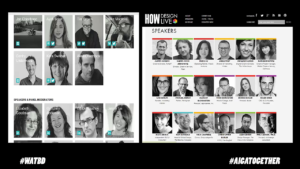

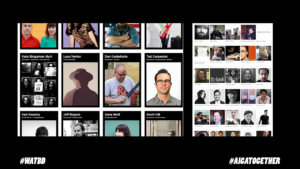

How many black designers do you know? Just think about that for a minute. How many black designers do you know? If you find that there’s not many or you don’t know any at all, that’s actually perfectly okay. That’s fine. And part of the reasoning I think behind this is that you know, we don’t really know where they are. We don’t see them because they’re not reflected in our design media.

They’re not reflected as we look at speaker panels that have majority white speakers. We don’t see them in podcasts, or hear from them—we don’t hear their voices.

We definitely don’t see them on blogs. We don’t read about them in magazines. And unfortunately that’s just what the design industry looks like. It’s a big monoculture and black designers are not part of that.

And now you might be thinking well, hold on a minute now. The reason that there’s not that many black designs out there is because we don’t know how the design industry breaks down by race. And you’d be correct in saying that. A List Apart started a survey in 2007 called Survey for People Who Make Websites. They did the survey from 2007 to 2011. And they got some pretty good insights about the industry. I wouldn’t say as a whole but they did get some good insights about it.

I managed to talk to Sarah Wachter-Boettcher, who is the current Editor in Chief of A List Apart. And one thing that she told me was that the survey was started to build a collective of the industry. You have to you know keep in mind now, 2007 the industry is still fairly new. Things are still really changing at a very rapid pace in terms of education, in terms of job titles. The industry is still growing and changing. And so the survey was a way to try to measure that and see where we were going or what the industry looks like at a particular time.

So while the survey does give that information, there are two important things that we have to realize. The first thing is that the survey was more of a reflection of A List Apart readers and An Event Apart attendees rather than the industry as a whole. This was something that Sarah told me, that the survey results really don’t tell the whole story. They reflect mostly those attendees and those readers, but you can’t really use this information and then make the claim that this is what the entire industry looks like.

A List Apart stopped doing the survey in 2011. And I asked her well what kind of challenges did you have with the survey in terms of putting it together, in terms of keeping it going. And there were you know, two things. The first thing was that it is super complicated. Finding out questions, adding new questions, removing questions unfortunately does not really lend any sort of historical relevancy to some of the results if you do that. Because if you ask a different question in 2011, you don’t really have a benchmark for years before that. It got super complicated to compile all the results and put them together into something that really gave a good snapshot.

And the second thing is outreach, you know. Reaching out to other groups. Again, one thing that she told me was that the results really kind of reflected AEA attendees and ALA readers. And so doing outreach to other groups that might be outside of that was something that they didn’t really have a whole lot of time for and so they stopped doing it.

Once A List Apart stopped doing it, unfortunately there’s no other organization that is really kind of compiling those hard numbers on the demographics of the industry as it relates to these sorts of things. Unfortunately that’s just what it is. So therefore what we look at the design industry, what we have to go off of, is what we see reflected in our media, in our conferences, our podcasts, our blogs, our magazines. This is what the design industry looks like.

So you might think, “Okay, Maurice. So black designers aren’t reflected in our media. What about top design and art schools?” I went to an art school. There was a black guy in my class. I’m pretty sure that that means that there are black designers in the industry.

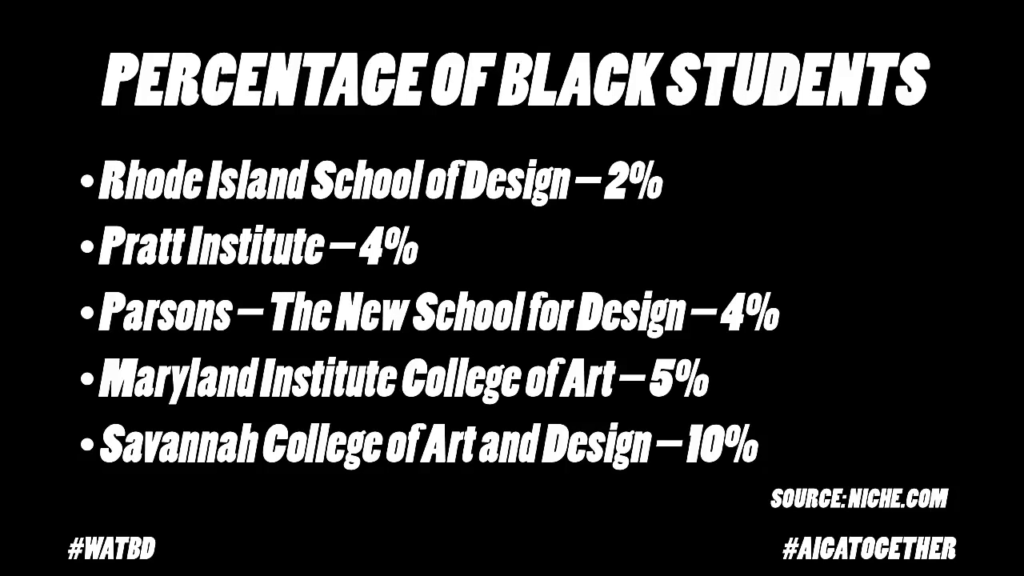

Well, yes and no. So, I looked at a couple of the top design schools here in the United States and looked at their percentages of black students. Rhode Island School of Design, 2%. Pratt Institute, 4%. Parsons-The New School of Design, 4%. Maryland Institute College of Art, 5%.

Savannah College of Art Design is 10%. I feel like this is higher for two reasons. The first reason is that the campuses are here in the South. According to 2010 US Census reports, a large majority of black people in general live in the Southeastern United States. It would make sense then that that would trickle into higher education in terms of attendee numbers or students. So that I can understand.

But if there’s one thing that I saw as kind of a nice, interesting parallel, is that these single-digit or low-digit percentages kinda mirror what we saw tech companies doing last year when they talked about the diversity numbers for their US workforces. So we see that even if we look at these big art schools to try to find black students, it’s going to be hard to find them there.

Now, why aren’t they in those arts schools? There’s a number of reasons for that. That could really be a whole presentation in and of itself. What I want to do is introduce someone to you.

This is Cheryl D. Miller. Cheryl D. Miller was a very prominent designer in the 70s and the 80s. And in 1985 she wrote this searing eighty-nine page thesis when she was a graduate student at Pratt Institute titled “Transcending the Problems of the Black Graphic Designer to Success in the Marketplace.” And this thesis lays out several reasons for why black designers are sort of starting behind in terms of their viability in the industry. There’s a lack of family support. The cost of art school and tuition and fees is way too expensive. There’s not enough financial aid. There’s a lack of mentorship. There are lots and lots of these points, enough really for an entirely separate presentation. I would love to discuss those in depth. We don’t have that much time to really do that here. But, there are a myriad of reasons.

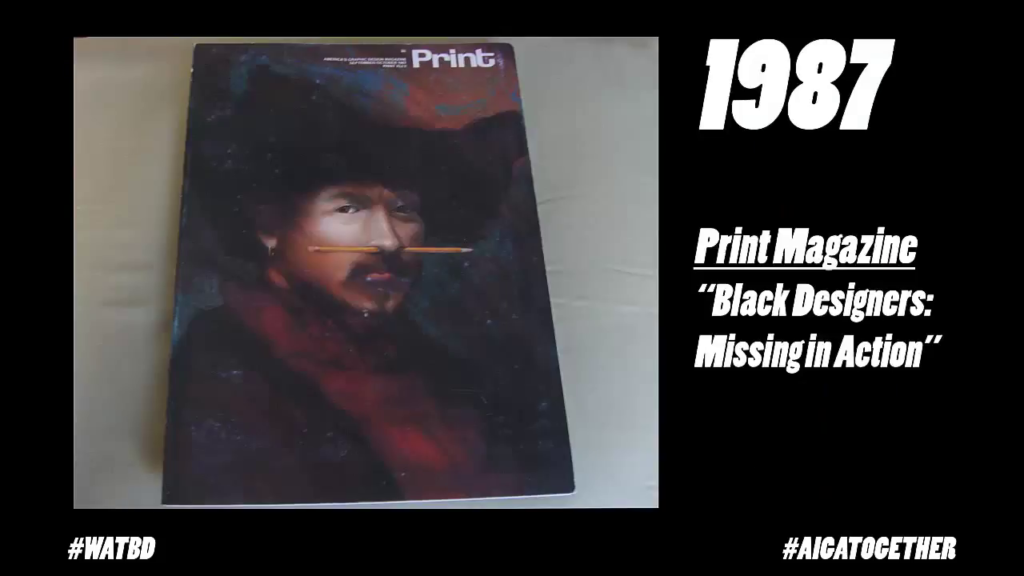

Cheryl’s piece inspired an article in the September/October 1997 issue of Print magazine. And this article was titled “Black Designers: Missing in Action.”

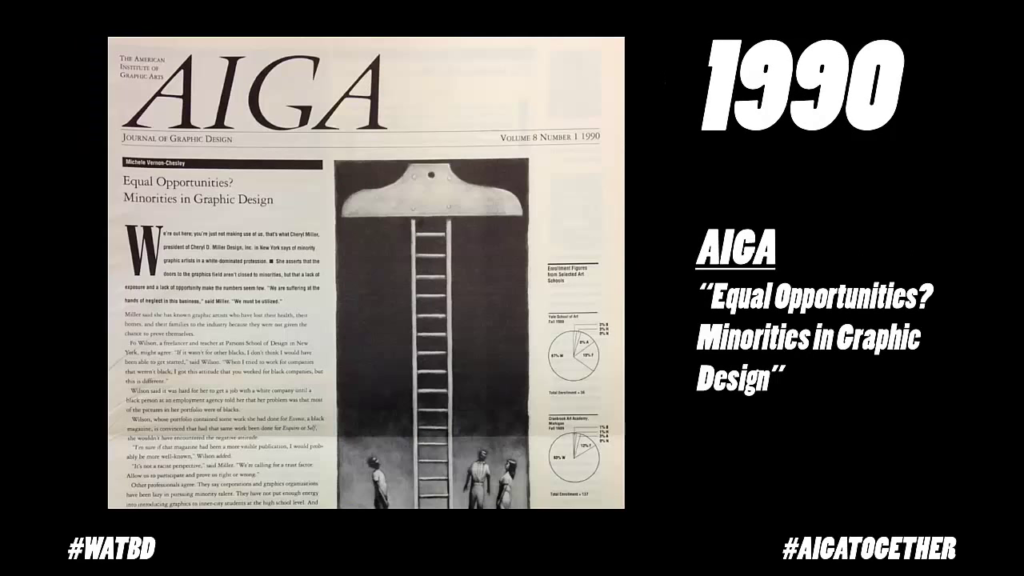

This article caught the eye of AIGA and Michelle Vernon Chesley, who wrote an AIGA Journal article in 1990 that was titled “Equal Opportunities? Minorities in Graphic Design.”

Now, this particular journal article asserts a few arguments. The first is that the graphic design field did not open up to minorities in terms of formal education until desegregation from the Civil Rights Act. So we’re starting in maybe say like the 60s, late 50s, early 60s, right. The other thing it asserts is that companies are lazy in pursuing minority talent. Third thing is that the pipeline, or what we know I think today as the pipeline, starts in high school or it needs to start in high school. Because then high school pushes them further to college, which will push them out into the industry. Starting earlier than that they didn’t really talk about, but they really sort of asserted that the pipeline starts in high school. And lastly, educators need to play a more active role as it relates to talking to minority students about design and things of that nature.

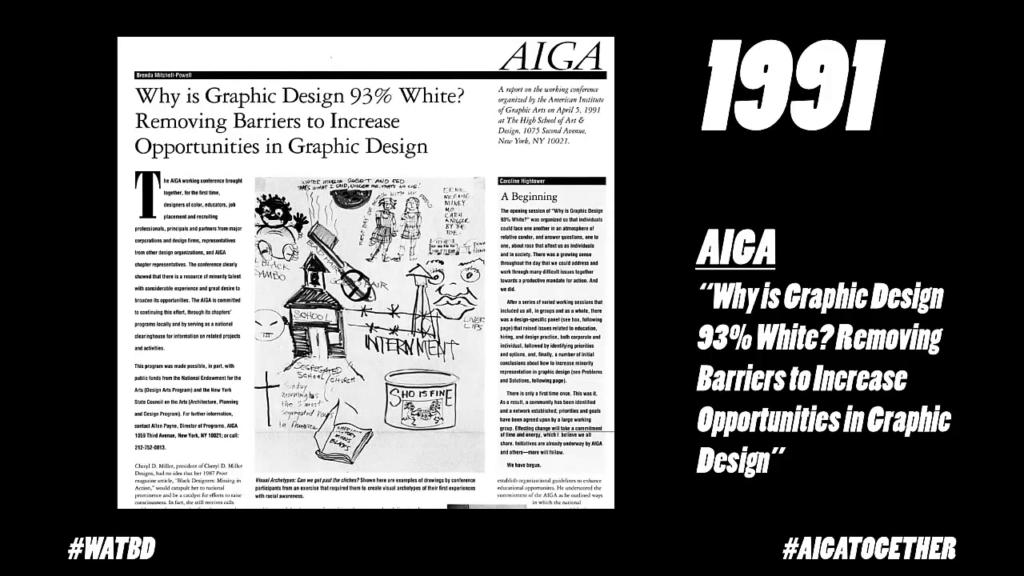

From this article there was a symposium that was titled Increasing Minority Representation in Graphic Design. This happened in September or so of 1990. And this was summed up in a 1991 report for AIGA that’s titled “Why is Graphic design 93% White? Removing Barriers to Increase Opportunities in Graphic Design.” This was done by Brenda Mitchell-Powell.

So from this, there was a survey. This survey was directed to 350 design firms, 235 design schools, and over 500 multicultural designers. And the survey results showed a number of concerns that I think that we’re still seeing to this day.

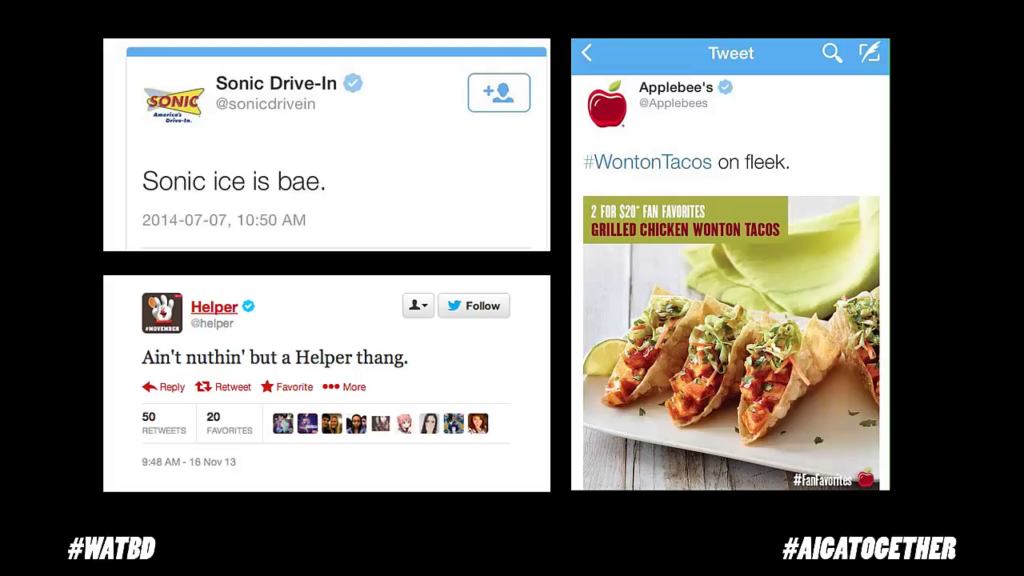

The first big concern is cultural exploitation. That’s something which I think we’re all seeing as brand say “bae” and try to be on fleek.

There’s stereotyping. One of those things you can see sort of reflected here, and this is an ad from Nivea Men that shows a black man hurling another black man’s head with an afro and a beard, with the phrase “look like you give a damn and recivilize yourself.”

And there are also corporate and societal assumptions of inferiority. A host of other issues. If you have a chance to really check out this 1991 report for AIGA, I highly recommend that you do that.

Also from this came a three-point initiative. This initiative was establishment of a mentor program for minority students or minority designers. The establishment of a job bank or program system. And the implementation of educational opportunities.

Now, this three-point initiative is something that AIGA has continued in part throughout the years, up until now which is what we see as as AIGA’s Diversity & Inclusion Task Force. For AIGA, diversity means facilitating chapter participation in multiculturalism. And this is happening at the chapter level, this is happening at the national level as well.

But here is the gotcha. AIGA does not and should not be the only organization that is having this conversation. As a trade organization that does have a lot of designers as their members that’s sort of what their purpose is. It makes sense that they would be in front of the conversation. However, they can’t be the only voice. They cannot be the only voice.

The standard that you walk past is the standard that you accept. Think about it this way. Do you own a business? Do you staff employees? Do you have a design blog or a design podcast that has an active community of readers or listeners? Do you host a meetup? Do you organize a conference? Do you attend meetups regularly and talk with other designers?

If you answered yes to any of these questions then you have a responsibility as a working practitioner in this glorious industry that we know and love as design to help improve diversity. And granted we are talking about black designers and diversity is a large spectrum. It doesn’t have to do just with race. It’s ethnicity, it’s gender, it’s sexual orientation, it’s nationality, it’s accessibility. It’s a lot of things. But as someone who is a designer in this industry, you have an obligation and a responsibility to help improve diversity.

Once again, the standard you walk past is the standard you accept. Because guess what? This 1990 symposium, this ’91 journal article? These same problems are persistent in the industry to this day, right? Twenty-five years is far too long for this industry to keep ignoring the lack of diversity present, whether it’s black designers…whatever. From schools to educators to working practitioners, we all have to do our part if this is something that we are serious about in terms of continuing the livelihood of our industry.

So remember this question I asked earlier, how many black designers do you know? That’s why I said it’s okay if you don’t know any. That’s fine. The current design media is reflected where you don’t see black designers. But here’s the thing, though. You have the power. We’re going to talk about solutions, because you really have the power. And you may not think that you have the power. But again, if you answered yes to any of the questions that I talked about before, you have more power and more privilege than you think you do in order to really start to make change. So we’re going to talk about some solutions.

First off how do we fix the lack of black designers present in the industry? Now, earlier we talked about outreach. So I want to talk a little bit more about that, delve into it a little bit more.

First off there’s mentorship. This is something from when I’ve interviewed people with Revision Path to even just talking with black designers here and there. Mentorship is something that is still sorely needed in this industry as it relates to black designers. It is crucial in order to bring them up to let them know about the tools they need to use and the knowledge that they need to have. It is very very important that they have mentorship.

The Inneract Project, which operates out of the Bay Area is an organization by Maurice Woods, who I’ve talked with. And what they do is they provide free design classes for inner city students, to help them learn about design to get them kind of on the track if they want to become a designer. It’s a great organization. I highly recommend you check it out.

If you don’t want to support the Inneract Project because maybe they’re too far away from where you live, look at your local AIGA chapter. As a member, you can talk about these things, you can influence change, you can talk to board members, you can talk to other members. Look at your local AIGA chapter. Get involved in the Diversity & Inclusion Task Force. We would love to have you. You know, the more voices the merrier.

If you’re not a member of AIGA (and that’s fine) look at local high schools. Look at local middle schools. There are talented students there that love to draw, love to design, but they may not know how do I really turn this from a hobby into a profession. Or moreso, how do I make this into a career. This is something that you can do. You can speak to schools, you can speak to students. Or you can even start your own group. If you don’t like kids and you just want to talk other adults or something like that, start your own group, you know.

The thing that you have to understand is that black designers—and this is not for all black designers. This is some black designers. We’re operating from a deficit in a number of areas. Exposure, education, inclusion. You don’t want to pigeonhole these people. Don’t just give them black or African things to do, right. Talk to them. Give them your knowledge. The gift of your knowledge and your input is crucial in terms of really supporting this industry and making it something that you can be proud of.

Outside of mentorship there’s also events. Again, if you put on a conference or put on a meetup, there are things that you can do to help make sure that you have more diverse attendees, more diverse speakers. Ashe Dryden has a wonderful post called Increasing Diversity at Your Conferences, which again this goes across the spectrum of diversity that I talked about earlier. You should check that out. There are things there that can be distilled down not just the conferences but to meetups, to other events, things of that nature. Coupled with outreach, those are things that you can do.

If you happen to own a design firm or a design agency or you’re in a position of management at a design firm or agency, you know, you can do things from a management perspective to try to bring in more black designers.

First thing you would want to do is to find a clear value proposition. From there you want to establish the facts, look at the root causes. Why do we not have more black designers? What are the reasons for that? I talked about some of these root causes earlier in terms of staffing, or where you’re looking if you’re looking at art schools or things of that nature.

From there create targeted initiatives. If you have something in your annual plan that talks about “we want to staff X number of black designers,” make a target initiative to make that happen.

From there you would want to define governance. Who in your company is going to own this task? Who in your company is going to be the one to see this through to make sure that it gets done?

And finally, once that’s done you want to build inclusion. It’s not enough to just bring in black designers or to hire black designers, but does your corporate culture, does your department really make sure that you’re including them, or are they just there as a token? Because if they’re just there as a token guess what, you’re probably going to end up losing them sooner rather than later. So make sure that inclusion is built in to bring them in, make them a part of your company culture, make them a part of your company’s family. What you don’t want to do is exploit them for profit, right. You don’t want to just bring in your black employee and then exploit them to make them do the work for you. That’s not what they’re supposed to do.

Now, granted this is not easy. It is not easy at all. This is going to be hard. It shouldn’t be easy. But you should be transparent and be truthful and I think that you will get the point across. Here’s the thing, remember how I said the AIGA should not be the only organization that has this conversation? It’s true. It’s very true. It’s going to take a sustained effort from a coalition of organizations, agencies, design firms, conferences, design media, etc. to really make this happen. It can’t just be the work of one organization. And like I said before it’s also not the responsibility from black designers or from designers of color to fix this alone, right. We got our own shit to deal with. But that’s a whole other presentation. But it should be up to us to fix a problem that we didn’t create.

So what are the benefits of diversity for the design industry? Like what are the the real-world benefits of doing this? Well there’s a couple of things. First thing is that you are creating design solutions that benefit a wider range of people from different backgrounds. What you don’t want to do is fall into the trap of homogeneity, where you only have people of a certain type in your company that are making decisions, because their viewpoints may only be to that certain type. Having more people at the table, having black design, having a diverse group at the table, ensures that you have a wider array of input so you can then make solutions that can really benefit a wider range of people.

Secondly, it solves the infamous talent shortage problem. Because guess what, you’re looking now in more places than you were before to find qualified people.

Thirdly, it prevents you from making stupid cultural gaffes that are born from homogeneity. What you’re seeing here on screen right now is an example of an ad campaign for Jeep in Argentina where it looks like this man is wearing blackface. Now, I’m not saying that they don’t have any black designers or they didn’t run this by any black people. But you know, this is bad. You don’t want this, right?

And also it’s good for business. I know that we’ve talked about this before in terms of the benefits of this for tech companies. But from the design perspective there’s a 2009 study that was published in the American Sociological Review that showed a positive correlation between racial and gender diversity, with increased sales revenue, profits, more customers, higher market share, and greater profitability. So how much money are you leaving on the table by not trying to bring in a more diverse workforce?

Now, to be clear, these solutions that I talked about, this is not a cookie cutter one-size-fits-all solution, right. You know your organization or your conference or your meetup best. So you will need to tailor your own program. But you have to make the concerted effort. As you can see, the benefits are there. It’s up to you on whether or not you’re going to do the work in order to reap the reward.

Now, where do you find black designers. That sort of is the question of this entire presentation? Where are the black designers, how do I find them? So, there’s a couple of places.

First, I’d be remiss if I didn’t do a quick plug for Revision Path and 28 Days of the Web. Revision Path, there are new interviews with black designers, developers, etc. every Monday 10:00 AM Eastern. We just celebrated our two-year anniversary. That’s a good place where you can start. Next is 28 Days of the Web, where for every day in the month of February a different designer or developer is featured. These are places where you can look. On 28 Days of the Web right now…this is 2015 so there are fifty-six designers there. Revision Path, right now there are sixty-nine, I think. Actually no we’ve done a hundred interviews. So there are podcast interviews as well as long-form interviews with people. So this is a good place to start. This is a great place to start.

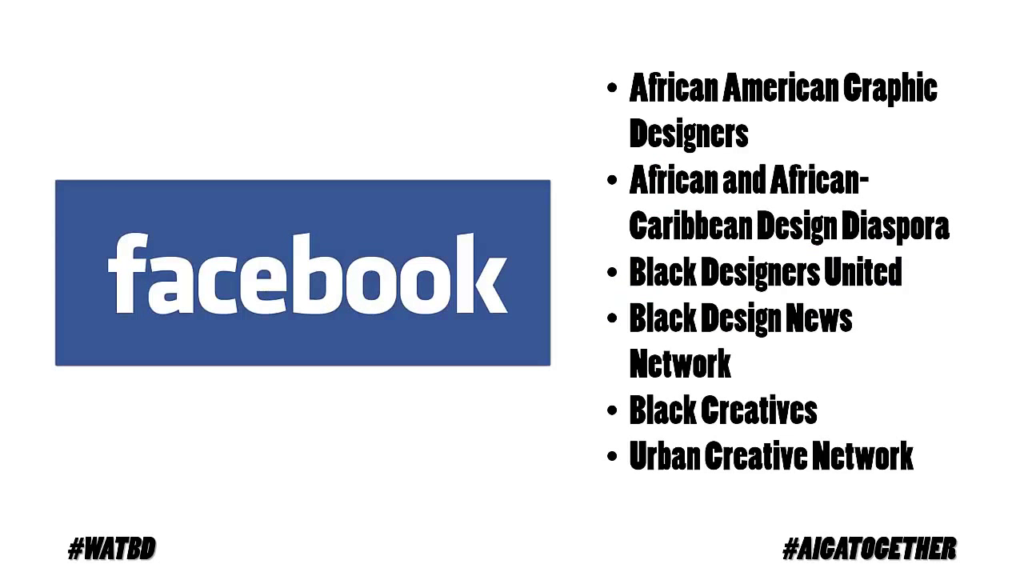

You might also want to look at Facebook. Facebook has several groups. Here is a list of them. These groups range from 400 members, which is Black Designers United, to over 12,000 members. So there are lots of members in these groups here.

You can also look at LinkedIn groups like ADCOLOR, Black Creatives, Urban Creative Network. Interesting thing about black creatives, they also have these regional subgroups. So if you’re in the Southeast there’s a Southeast Black Creatives or something like that which can help you drill down even further to try to find people.

Now, many of these groups are private, closed-off, invite-only. But that’s sort of par for the course when it comes with these types of things in the design community. Just like any types of these groups, once you gain access ask yourself, “Am I adding value or am I just an interloper? Am I just lurking?” In order to get value, you need to add value. So maybe you share information about calls for proposals. Maybe you share information about job openings, things of that nature. These are things you can do to add value and then get value back in return.

Also, one huge source that should not be overlooked are HBCUs. HBCU is an acronym for Historically Black Colleges and Universities. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention my own alma mater Morehouse College here at the top. But Spelman College, Howard University, Hampton University, Florida A&M, Jackson State University. These are just a handful of HBCUs that you can start to look at.

Now, there are some HBCUs that don’t even have a dedicated arts department at all. But don’t let that deter you in your search. Just because there’s not a dedicated our department does not mean there are not people there that are interested in design, right. So look there at HBCUs, that’s a great place to look.

You can also look at your own network. Because you know, everyone’s got a black friend, right. You see her right there in the beanie. Ask your network. You’ll probably get one of two scenarios. One, they may not know anyone either. That’s okay. But, they may know someone who knows someone that would be perfect. That’s the other scenario. But you won’t know unless you ask. Unless you put the question out there, that’s how you’re going to know.

And lastly, you have to look at yourself. Look at your organization, your meetup, your firm, your agency, your corporate culture, and ask yourself this: What are we doing that might be turning black designers away? What are your core beliefs? What are you not being clear about as it relates to your corporate culture? Are your perks that are listed on your career page filtering people out on purpose? You know, these are things you have to be brutally honest about. If diversity is one of your core values, you have to look within and say, “Well what do I need to do in terms of changing the culture and making this something that designers that do not fall into the mainstream would be interested in?”

Now, to be honest this makes you feel bad. This will make you feel guilty. But that’s fine, that’s good. Guilt encourages you to have more empathy for other people, to make corrective actions, and to improve. And I think we all know that there’s nothing that designers like more than solving problems. It’s what we’re good at.

So in conclusion I just want to say that change is a process, not an event. People like Cheryl D. Miller have done the research and laid out the groundwork for this issue nearly thirty years ago. AIGA has done their part to kind of keep it going, with their symposiums, with these journal articles, and even now with the work that’s done with the Diversity & Inclusion Task Force. But it can’t just be up to one person. It can’t just be up to one organization. Change is a process, not an event. This is something that if we as an industry are serious about diversity, it’s going to take a concerted effort from media, to conferences, to educators, everyone, to really make sure this happens. In 2015 it’s time to stop making excuses and start making change.

So I want to give special thanks. Of course I have to thank AIGA for these articles, for the work that they’ve done, for the national Diversity & Inclusion Task Force. I have to give a huge thanks to AIGA.

Also have to thank all Cheryl D. Holmes-Miller. Cheryl right now is a clergywoman. She lives in Connecticut. And because of this work that she’s been doing for so long now, she’s now interested in getting back into talking about this and teaching and really getting back out there. So huge props to her for the information and the conversations that we’ve had.

Big thanks to Husani Oakley, who’s a good friend as well as my mentor. Thanks to my GoFundMe supporters, Erica Mauter, Alexandria Eddings, Chanelle Henry, Brian Douglas, Jessica Ivins, Jacinda Walker. Thank you to Sarah Wachter-Boettcher from A List Apart for talking with me and give me insight about the survey that they did from 2007 to 2011.

Thanks to all the guests that I’ve had on the Revision Path podcast. All of you, all the people that I’ve profiled with 28 Days of the Web. And of course thanks to you. Thanks to you for being open and receptive. To listening to this. Hopefully you really got some great information out of this that you can use to then go forward into the industry and start to make the change. So that way when someone asks you the question of where are the black designers, you can give an answer. Thank you so much for listening to this presentation.