Michael Hanemann: Hello. I’m Michael Hannemann. I’m a professor of economics here at ASU in the business school and in the School of Sustainability.

Water is full of paradoxes. Water is essential for life, cable TV as far as I know is not essential for life. Yet many Americans spend more money each month for their cable TV than for water in their homes. A gallon of gas costs a bit over two dollars. A gallon of milk costs about three dollars. A gallon of orange juice, maybe four dollars. And you have to make a trip from your home to get these items. The water comes directly into your home and you pay only two or three cents a gallon. In Phoenix we live in a desert city. We rely on the Colorado River for a significant part of our water. For the last sixteen years there’s been a major drought in the Colorado River. Yet, water bills in Phoenix are among the lowest bills in any city nationwide.

Now other commodities—food, clothing, shelter—are also essential for life. Yet water arouses passions that are not found with other essential commodities. Around the world, water is seen as something that should not be treated as a commodity. People see water as a human right, as something you shouldn’t have to pay for. The pricing of water has been a political flashpoint.

In Tucson forty years ago, the city council learned this the hard way. Water revenues were not keeping up with costs, and the water system was running out of capacity to meet peak summer demand. Water rates were raised to finance the improvements. Overnight, water bills skyrocketed. A recall election was promptly held, and the city council majority that had voted for the rate increase was booted out.

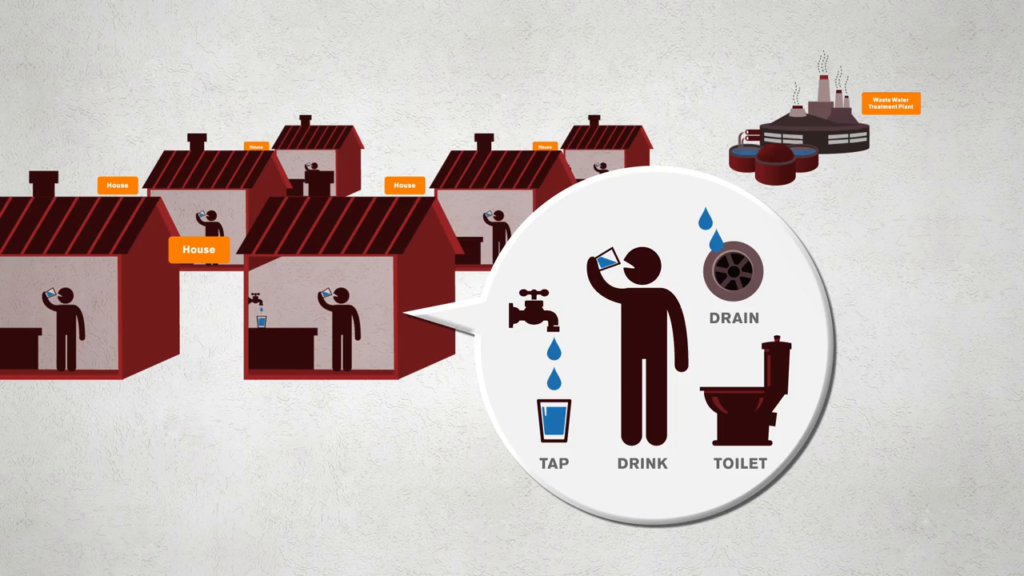

The economics ought to be simple. Water is not a man-made commodity—it falls from the sky. And in fact the economics is surprisingly complex. Water is a difficult commodity. It is free, and yet costly. It is simultaneously a private good, and a public good. It helps cities flourish financially, but now it is their financial burden. Almost nobody pays for the water per se. The cost of water is the cost of making it available at the right time, in the right place, and with the right quality. It is the cost of collecting, storing, transporting, and treating the water.

That’s why the cost of water in Phoenix is so low. The water is cheap, the infrastructure is new and doesn’t yet need much repair. In Boston, or Chicago, or Detroit, the water is abundant but the water infrastructure is old and expensive to maintain, and therefore the water is expensive.

The cost of water is overwhelmingly a capital cost. The entire supply chain, from source to tap, has to be in place before a single drop can be delivered. It’s not modular, and there are powerful economies of scale. You would not set out to build a dam or an aqueduct now and then expand it ten years from now when demand grows, the way you might do with a factory. That would turn out to be way too expensive. So you must overbuild, often decades ahead of demand.

In 1800, water supply was highly decentralized. People took water from a nearby well, or a pond, or a stream, or from a water pump in town. There may have been a vendor going around selling water. But as urban populations mushroomed in the 19th century, the need for a network-scale water supply became very pressing. With the growth in urban population, local streams became polluted. So more distant sources of water were needed to keep up with the growth of cities.

As methods of water treatment became available, drinking water had to be financed. This network was massively expensive. Today, the situation is different. The water and wastewater networks are aging and crumbling. And the cities are short of money. In many cities, there is intense political pressure to keep water rates low. The result is that while water rates cover operating costs, they don’t fully cover the cost of maintaining and replacing the water infrastructure. This cannot continue. Many of the current pipes were put in soon after World War II, and they are reaching the end of their working lives.

Over the next twenty years, the cost to replace urban pipe networks may reach a trillion dollars nationwide. It does not include the cost to meet new drinking water standards that will be required for the ever more exotic contaminants that show up in our water.

Then there’s climate change. With climate change, droughts will be more likely in many areas, including the Southwest. If there’s a drought and the utility delivers less water, the cost per gallon goes up. For water supply, there’s a schizoid aspect to climate change. The warmer air puts more moisture into the atmosphere, which translates into more intense precipitation. But that can be combined with greater dryness at other times of the year. The result is a less-reliable water supply. A solution is to have more storage. But storage is extremely expensive. We will end up having to spend more money to get the same reliability that we used to have in the past.

And this is the larger reality that we will all face. Maintaining the water supply that we have now and that we take for granted is going to become far more expensive. So viewing water as a commodity that one pays hardly anything for is just not going to work for the future. Thank you.