Dan Klyn: It’s so good to see all of you here and to think about the thousands of other people all over the world today who decided that instead of being outdoors in the sunshine and spending time with our families that we would spend the day to talk about information architecture together. And let’s have a big round of applause, and it’s the end of the day. Why don’t we stand up and applaud the organizers of today. You’ve done such a spectacular job. Thank you! Thank you. Thank you.

So let’s see if my computer will behave. I’m sure you don’t want to look at Pink Floyd. Okay. So, before we begin I would like to make a shameless tiny bit of self-promotion. My company is called The Understanding Group, and we’ve been a sponsor of World IA Day since the beginning. And three of you have received a copy of Richard Saul Wurman’s book Understanding Understanding compliments of Mr. Wurman and The Understanding Group, so thank you for playing along and looking under your seats. And if you have any questions about how to redeem your book, just ask me a question.

Okay. So, I’m from a state in the United States called Michigan. Has anybody here been to the state of Michigan? A couple of you. And that’s my son Garrett, so he’s been there too. The state of Michigan looks like a mitten, and so when we tell people where we’re from, we point on the hand and say where are we from. So I’m from here, Hudsonville, Michigan. And I get to teach here, in Ann Arbor, Michigan at the University of Michigan School of Information.

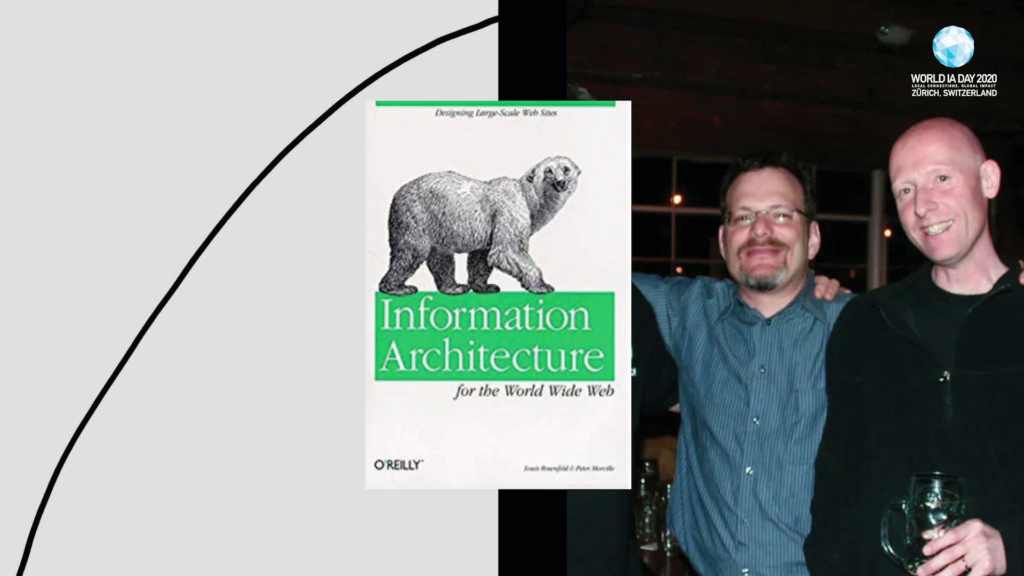

And this School of Information is part of the history of our field. I’m curious if any of you have seen or used a book with a polar bear on the cover. Some of you have, yes. So Peter Morville and Lou Rosenfeld—and I think it’s true that Peter Morville was a speaker at your very first World IA Day here in Switzerland—these two gentlemen were studying Library and Information Science at a school that had just changed its name from the School of Library Science to the School of Information and Library Science. And at the time that they were studying, the World Wide Web became important. And it became so important that the otherwise lowly profession of librarian suddenly was aggrandized as the important profession of information architecture. So it’s a strange trip from the library to the World Wide Web, and the idea was that if librarians know how to organize information in a library, perhaps those are the people who should organize information on the Internet. In retrospect I’m not sure that was the best idea but that’s what happened. And so the arc of the history of this field is connected to the place that I get to teach and to people that I know and love and that’s pretty fun.

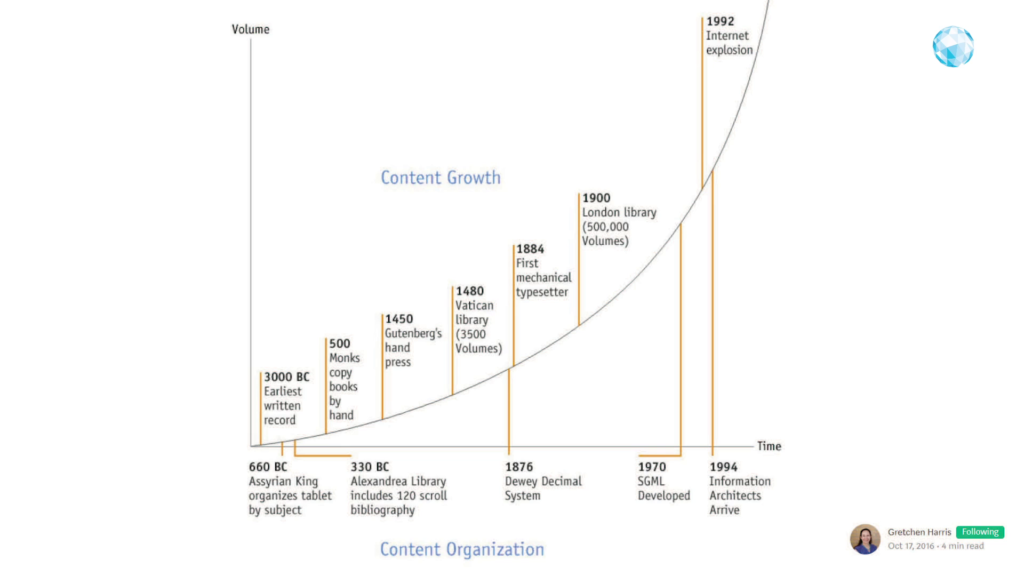

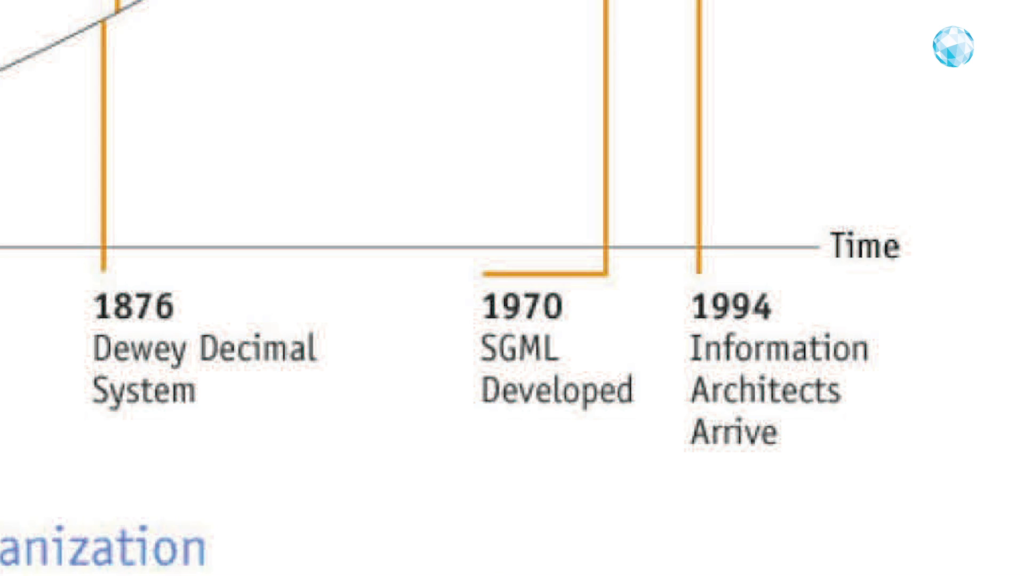

And some people trace the need for information architects and the existence of information architects to the growth of complexity in information, in data. And here are all kinds of—from Gretchen Harris’ lovely Medium post about the history of information architecture. I think this graph is from the Polar Bear Book. I’m not quite sure; I should’ve looked that up. And interestingly to me, my dad is a history teacher and I’m very interested in history…

There it is. 1994, “Information Architects Arrive.”

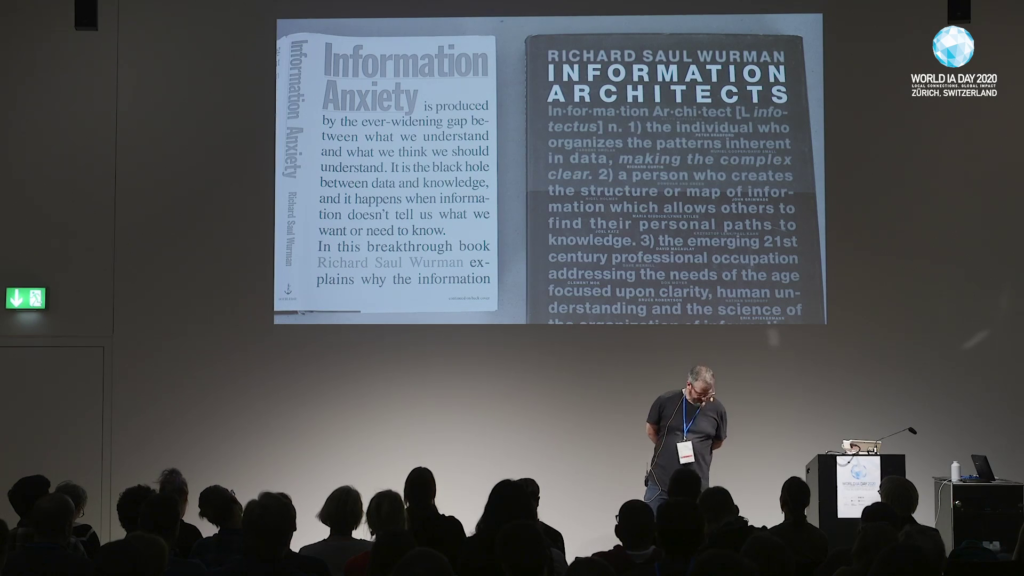

That’s not true. In 1976 Richard Saul Wurman invented information architecture at a conference for architects. And Richard Saul Wurman’s sensibility around information architecture is that it’s…architecture. It’s part of how we understand and shape the built environment.

So that was in 1976 that he was talking to architects about information architecture. They did not find it interesting or compelling. Nobody really did anything with it. Until, per the previous slide, in 1994 or so librarians took this word “information architecture” and ran with it.

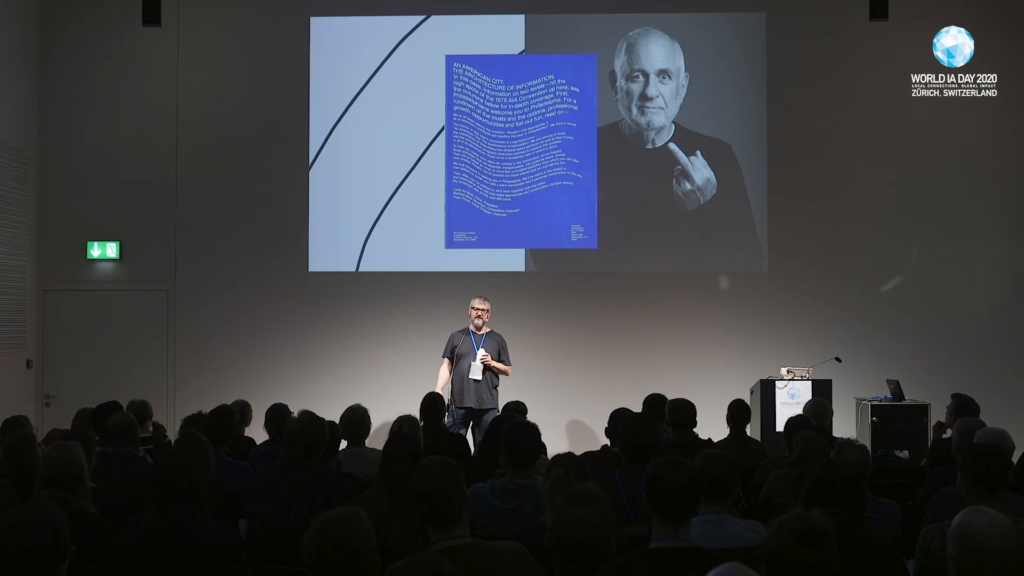

So in about the same time as the Polar Bear Book came out, Richard brought this book out, Information Architects. And this was an anthology showing many different designers’ implementations of the idea of information architecture. Which for Richard at the time that this book came out, the shorthand for information architecture would be “making the complex clear.” Yes. Andrea kindly brought a copy of some of the books that I’ll be referring to today.

So the arc of the history of this field… There’s the arc of librarianship, and the growth of the complexity of information that librarians can respond to. There’s the arc of architecture, at least in the United States in the built environment in the 70s. And in the Bay Area of the United States, where one of Richard’s businesses was located. In the 1980s and 90s, talking about information architecture more like we talk about it today. But as some of you know, at the time that this book came out, just before the Polar Bear Book came out, almost no conversation between these two different ways of talking about, thinking about, and practicing information architecture. So, the arcs don’t touch. They are a little bit separate.

If we keep going, if we keep asking the question of the emergence of information architecture, how did this happen, why is it a thing? And inspired by Richard’s creation of information architecture inside of the field of architecture, I’ve been looking for other sources, other provocations and culture that made information architecture have to be a thing. And one of the more interesting critics of architecture, Kenneth Frampton, talked about how really some of where all of this begins is with the Industrial Revolution. And in particular a World’s Fair in London in 1851 that was called the Crystal Palace. And that’s a picture of the Crystal Palace. It was an amazing phenomenon. This was the beginning of World’s Fairs as an event, as something that people do.

And you were there. The World’s fair was presented in 1851 as The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of the Nations of the World. And so in the Swiss Pavilion there were all sorts of products that were examples of industry and progress.

And what Frampton says that I’m interested in is the idea that one with this explosion of industrialization, with the explosion of the means of production…and as we know, these means of production word mostly held closely by wealth and power, that there’s something about the Crystal Palace and the phenomenon of a World’s Fair that is meant to engage the public. And the basis of this engagement with the public was a celebration, a festival of how you would do things. And for Frampton he thinks that this is an important time in human history. Because for the first time there was a surplus of means over ends. And the question of all of the things we know how to do now became more important and was pushed into the public sphere over top of the question of what. What have we done? What is this thing? That question was pushed down as the celebration of how and the surplus of means was presented to the public.

And again, the ownership of these means was primarily the people who already had power and wealth. And so, the public was engaged in order to protect power and wealth through the beguiling of the public with this display of the awesome works of the industries of the nations of the world. And they needed us to be beguiled by all of the surplus of means so that we wouldn’t seize the means of the ends, perhaps.

So, engaging the public on the question of what we care about, what are we focused on? We’re focused on how over a focus on what. And so with this surplus of means over ends, with this new partnership between art and architecture joining forces to bring the public into a new time, a time when what things are and what things seem like can be split apart.

This is an illustration that Google created to help sell the idea of a connected city in Toronto. And I think what’s going on in this picture is that a couple who had a small apartment are now more successful and wealthy because they have embraced this new world. And they have been able to knock a wall out of their apartment and move into the adjacent space. And because they liked the wood grain of the beams on the ceiling in their old space, they can just hire somebody to paint the door frame, just paint on that wood surface to make it seem like it’s part of everything else. Nothing has to be or remain as it is or as it appears to be.

So this fascination with how over what, part of it is to be freed from the constraints of what things are. With the surplus of means, with the surplus of how, we can change what things seem to be to more suit our liking. And we’re perhaps more attracted to that.

When Richard Saul Wurman, the inventor of information architecture, was a 5‑year-old boy…or 4, I’m not sure, the first memory that he has as a child was holding his father’s hand and going up an escalator at the 1939 World’s Fair.

And the organizers of this World’s Fair in 1939 were interested in helping the country recover from what we call in the United States the Great Depression. And so staging this amazing yet another instance of a World’s Fair, in some ways a continuation of what happened with that first World’s Fair in 1851, the agenda of the people who were promoting the fair became even more explicit. And so the quote here is from one of the organizers of the World’s Fair in New York talking about we can exhibit all of these wonders that technology brings in such a way that it will establish a pattern that the people can then follow. That they won’t have to think for themselves. That we can think on their behalf because we know better. There’s a better way to live, and we know how that way is.

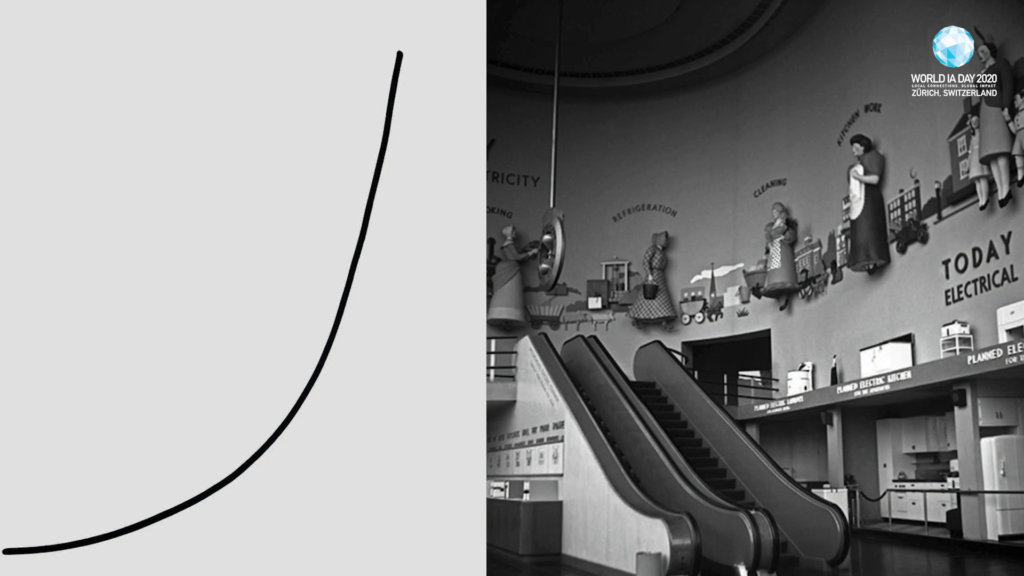

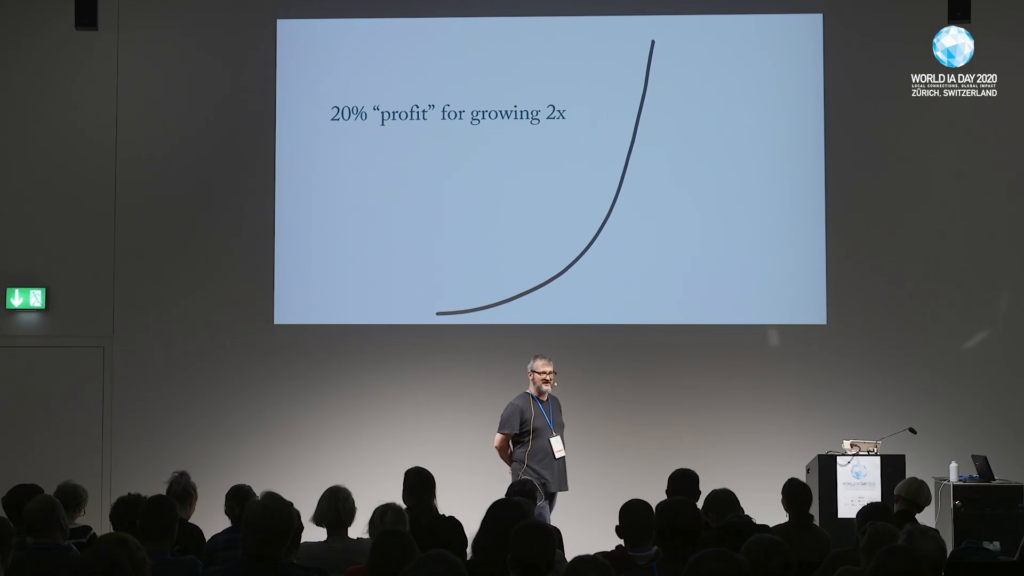

And that’s the pattern that has prevailed ever since. And maybe all the way back to 1851 to that first World’s Fair. A superlinear growth curve that just keeps going up steeper and steeper, faster and faster. This is the growth pattern that I am expected to deliver for my clients, and I think that most of you all are expected to make this pattern work for your clients.

And I don’t know for sure but I think this could have been the little escalator that little Ricky went up with his dad to go see…it’s a little unclear in the picture. This is Westinghouse, the electronic consumer goods manufacturer, showing a progression from gadgets that help you with cooking back when we wore bonnets, to the invention of refrigeration, and now our clothing style’s a little bit more modern. Now we’ve got all sorts of devices and machines for cleaning, and kitchen work. And it leads to a liberated woman wearing a suit coat now, not a cleaning smock. And her children are her accomplices, not her shackles. All through the wonder of this technology, all as we ride this growth curve up and up to a better world.

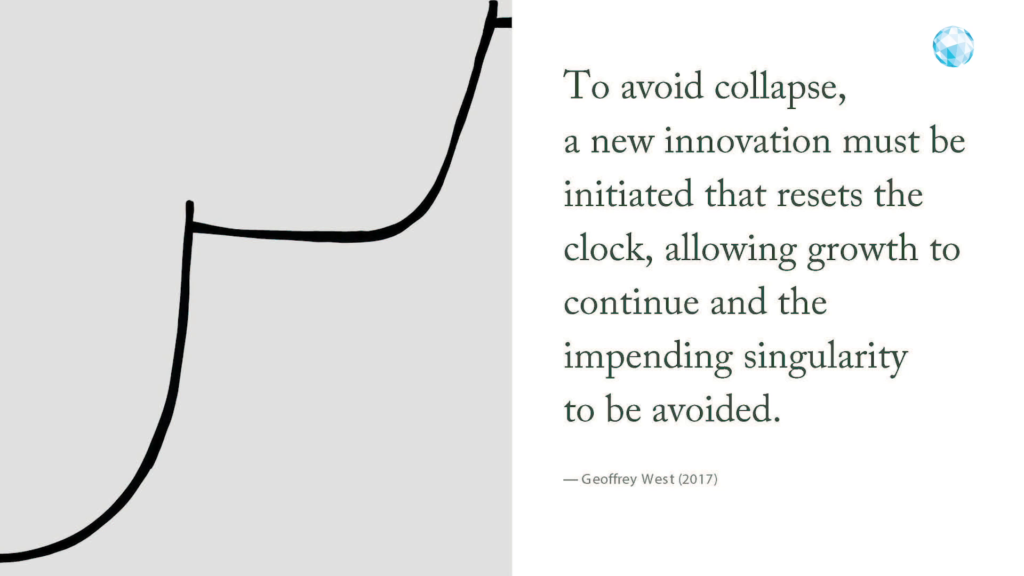

There’s an American physicist named Geoffrey West. This is one of two Mr. Wests that I will invoke today, both Americans. Geoffrey West, as a physicist working at the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico in the United States, started using his mathematical knowledge as a physicist to look at what are people doing in the world, what are the patterns of human activity. And he also used those patterns to study the natural world. And what he found out, or what his work seems to prove is that the works of men, the works of mankind, following that superlinear unbounded growth pattern have built into them, fundamentally, unavoidably, always, a total system collapse. That this pattern is not of nature. This pattern of superlinear growth is nothing that our universe…does. This is something that people do. And this is one of the reasons why we can’t have nice things.

And it gets worse. So, to forestall the collapse, we have to innovate. And the purpose of an innovation—and I think information architecture is one such innovation, and I think we are co-responsible, we are…this is us, we’re part of this. What is information architecture? Why is it a thing? Why are thousands of people spending a Saturday talking about it instead of doing something else? This innovation pushes the collapse further forward in time. The use of information architecture to help manage complexity which is a product of that inappropriate, insane growth pattern, what that does is it pushes the disaster farther into the future.

And that’s good. And thank you information architecture and information architects for doing that. But there’s a nasty secret here. Which is that the interval for the next innovation…because it’s still gonna collapse because we’re still following that pattern. Each time that you apply an innovation to push the event horizon of doom further into the future, the interval within which your next innovation must surface becomes shorter. So, we don’t have an unlimited number of innovations to keep pushing the hockey stick shape of growth forward. Each time we innovate and we push the end further ahead in time, it shortens the amount of time in total that we have to address complexity and problems. So this is…this is not good. I’m just gonna say it, this is not good.

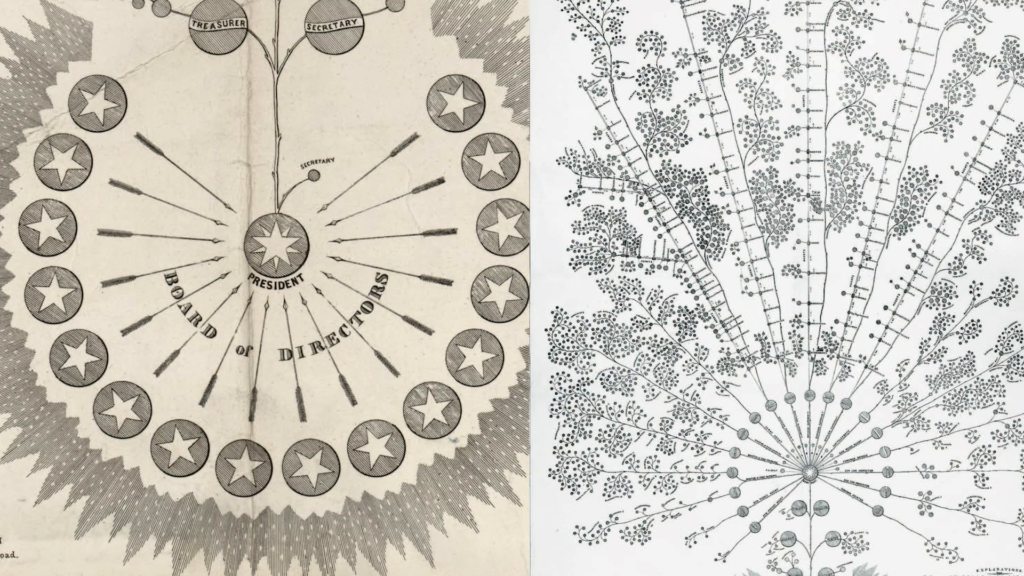

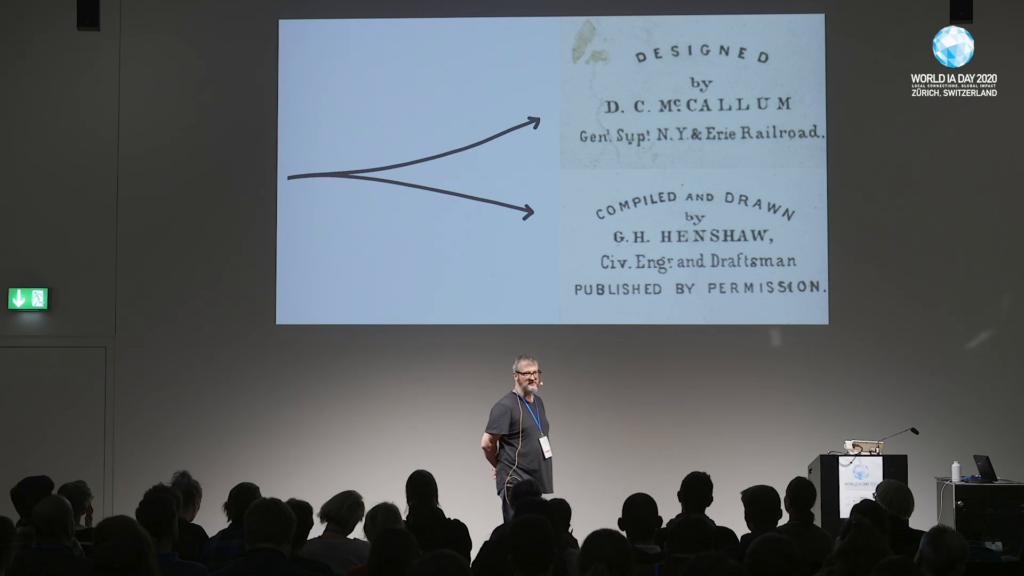

An example of this superlinear growth and the collapse, and back to the question of what is the arc of the history of information architecture. David [Weinberger] in his book…Everything is Miscellaneous I believe is the name of the book, he talks about how an American manager named Daniel McCallum invented the org chart in response to a disaster. The New York and Erie railroads had merged, and neither of those railroads had had disasters at a large scale prior to the merger. And shortly after they merge these organizations, two different trains collided head on. And I don’t know if you have this expression in your language, “trainwreck,” as a way of talking about a big problem? This was perhaps the origin of that. A literal trainwreck caused by a hyper linear growth pattern of a private company. And then the development of the innovation of information architecture to manage that new complexity, to help make there be no more trainwrecks.

The diagram is pretty famous. And those of us who do a lot of work with stakeholders, I think this diagram has got a fascinating… How about spearholders? How about pointy-thing-with-power holders? And what this diagram shows is that all of the power of the stakeholders can be managed and flow up through the organization. Because it got so big that nobody knew what all of the parts of it were anymore. And what information architecture did here was make it possible for that to continue to be the case.

So rather than using an innovation to help the organization understand its growth, or to disseminate more information across the organization, this was a mechanism to make sure that the information still didn’t have to be known by everybody. Because again, these are the people who have the power. The information architectural innovation here is simply to support the splitting off of the knowledge of the whole system into isolated bits of knowledge about parts of the system, in a way that would allow the thing to keep growing, keep growing, on a continent that was being conquered incrementally through railroads.

And as this is the age of industrialization, what’s really happening here is not only the splitting off of the knowledge of the whole from each of the parts. We’ve also started to do things like splitting off the job of rendering a diagram from the job of knowing what the diagram should be. As Hannah Arendt might say, the separation of work and labor. Which again I don’t think is working in our favor.

But it is working to support this pattern. And I believe that the fundamental innovation of this kind of information architecture was to help this phenomenon to continue to be the mode. To split off what our human nature, our human understanding, clearly knows is wrong from what business says is right. So we need to split perception from the human body. We need to numb the participants in this pattern. Because we all know it’s wrong. And we’ve colluded in this project to allow ourselves to be numbed from the effects of this terrible pattern.

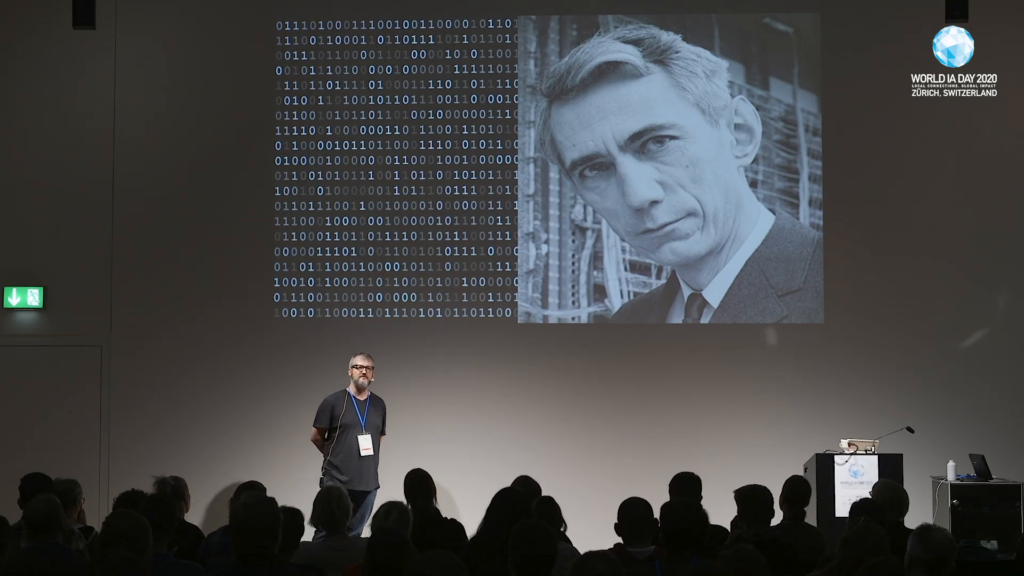

The University of Michigan is responsible for this in some ways. Claude Shannon, the father of information science, is a Michigan man. And you might know the famous saying of Claude Shannon in inventing binary as the means for moving information around in the world, Claude Shannon said that context is irrelevant to the problem that he was solving, which was making information be digitized and easy to transmit. So forking off…just like we fork off human perception from human bodies, we’re also forking information away from its context, separating it—again, to my interpretation. Because if information were in context, we might understand that we’re doing it wrong.

I feel like what Claude Shannon did is the supreme realization of the avant garde philosophy of the 17th century, the perfect implementation of Cartesian thinking, that you can split up the world into little boxes and then study each box separately, and then once you understand what each little box is, you can somehow then know what the whole is. And of the problem with this—there’s lots of problems with this. What’s being observed here by Kent Bloomer and Charles Moore, two American architects, is that with Cartesianism, the relationship can seem more precise because we’ve got them captured in the diagram. But what we lose is quality of location. Because the location doesn’t matter anymore. Claude Shannon freed us from the need of information traveling with its context. And the information architecture innovation freed organizations from having to know everything about themselves.

The practice in philosophy…Edmund Husserl called this bracketing. And a dirty joke is what do you call a collective of UX designers? An “it depends.” So we don’t have to really know what’s in the brackets. We can just bracket it, and whatever goes in the brackets is whatever goes in the brackets. This is lorem ipsum, this is a lot of the things that you and I do every day.

And this is how the places made of information that we all live and work in every day are primarily constituted. A Cartesian grid, with lots of rectangles, that can be populated by…it depends.

And it’s only going to get worse. And back to the question of what is reality… Is reality here? [points at the palm of his hand] Or is reality here? [moves his arms to indicate the space around himself] The answer…in about a minute. Here’s a squished graphic showing the growth curve of the sale of consumer-grade virtual reality technologies like headsets and gloves and such. It’s about to be the world. We’re almost there.

And if Cartesianism is our only way of doing this, we’re in trouble. We’re already in trouble, we know this, but we’re in for more. There’s an American farmer/philosopher named Wendell Berry who said it very powerfully, “Field = forest = parking lot.” It depends. Any one thing that can be serviceability swapped out for any other thing is equally fine.

What Geoffrey West found out, or at least his work claims that this is true, and one of the explanations for why are the works of mankind is so obsessed with delivering on this pattern, is that every time that you double an organization that is following this pattern, every time that you can get it to double in size, you get 20% profit, automatically. All you have to do…if something is growing at this rate, in this way, your job as the manager is to make it double. And once you make it double, you will have profit.

Ted Nelson, one of the innovators of computing, started one of his books on computing by saying, “Any nitwit can understand computing, and many do”. What this pattern says is that any nitwit can be a successful businessperson, and many are.

All you have to do is keep making something grow more, and keep the people involved numb enough to keep doing it for you, and you can be a successful operator.

This is a screenshot that I took several years ago. I teach at a university and so naturally I reuse pictures all the time. And I think it’s about time to retire this one because this is now. I used to use this a couple years ago to shake up the class, to get us thinking about oh my god what kind of a world are we living in. This is now. And I think the reason why what is it, 57,000 new things being added to…and these things have IP addresses. Think of all the other things. 57,000 new things with IP addresses being added to the Internet every second is because somebody needs to double their business. So they can keep growing, and they can look successful.

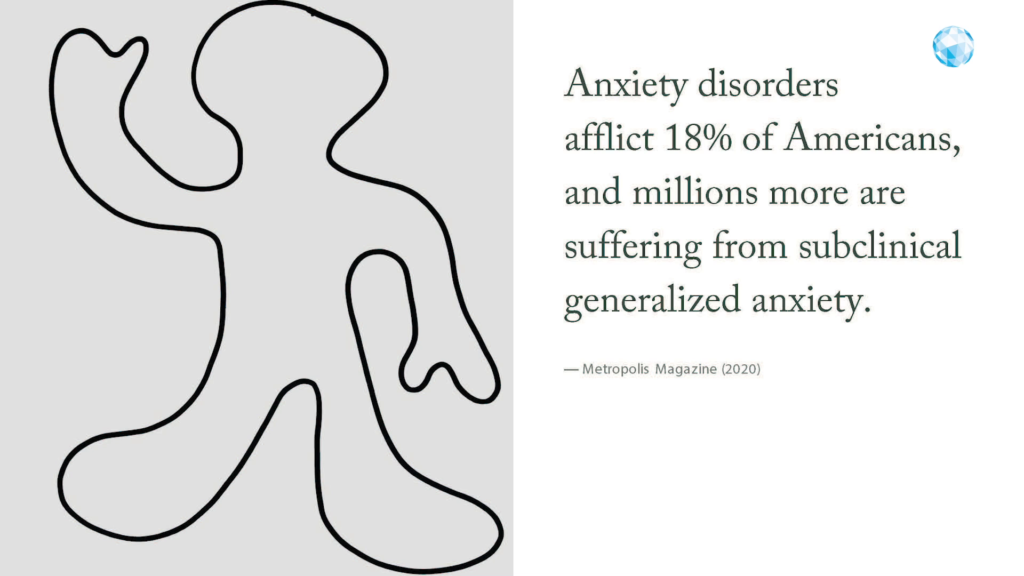

Which takes me back to Richard Saul Wurman. The book that came before the Information Architects book, but it came after he invented the idea of information architecture is Information Anxiety. And I’m curious if you have had the same experience that I have had, which is that anxiety isn’t something up in my head. Anxiety is something that’s in my whole body. It’s something I feel. And it might even be a gift to feel anxiety.

But it’s a gift that too many of us Americans have. I don’t know about you all, but we are feeling anxiety or we are experiencing disordered life because of anxiety at a rate that is alarming.

And as the philosopher Martin Heidegger observed, when we are depressed, when we’re feeling anxiety, we start to lose our proper connection with the world, of things. So 57,000 new things being added to the Internet every second, the onset of information anxiety, too much information, too much complexity to take in because of this growth pattern, consequently we are losing our ability to relate to things in the world in a fruitful, proper way.

And so what we do? We have to shut down the anxiety. We have to stop feeling this in order to keep going. The American poet Cowper said it this way,

Tis pleasant, through the

loopholes of retreat,

To Peep at such a world,

to see the stir of

the great Babel;

and not feel the crowd.

And I love this illustration. This is from an issue of the magazine Progressive Architecture in 1961. The first time that Richard Saul Wurman’s work as an architect was published. This is a little cartoon. It wasn’t attached to anything he was doing in there. Just a little artifact.

So through the peepholes. Managing so we don’t have to actually feel, or hear, or be in the crowd. Governing it through the little rectangle. That…is only gonna last for so long. And so what do we do? Back to that pairing of…I’ll use the props. What do we do about information anxiety? [holds up a copy of Information Anxiety] And back to what happened to the United States with the trainwreck. An architecture. [holds up a copy of Information Architectures That an architecture can be one response to anxiety.

And another American chap named West I think is a terrific architect, innovator. And what he does has a lot to do with what I think Richard is talking about. So I’m going to show you a little video here and then I’ll talk about what I think is going on.

[recording omits clip]

Kanye West very publicly struggles with mental health issues and anxiety. He ended up canceling this tour about halfway through. But I think what he was doing was an amazing act of architecture in response to the anxiety of how do I relate to things in my world now that this world has become the way that it is? And Kanye’s answer here is to not reuse the how of every other concert I’ve ever been to. We had crappy seats for this concert. I was expecting the stage to be at the front of the room the way that the stage is always at the front of the room.

And what I see Kanye West doing here—I haven’t been able to talk with him about this yet. But he changed the situatedness of the things in the space to change his relationship with the audience, to change his relationship with his music. It transformed what were going to be pretty crappy seats on one side of the auditorium— This completely amazing innovation that he came up with, a new way to perform for people in an auditorium. Every fifteen minutes or so we had terrific seats. And all those people down on the floor, he was right there. It was amazing to watch the stage move back and forth, to watch the people moving back and forth. And at the end of the show, it tilted down and he just walked out of the auditorium. It’s completely amazing. It blew my mind. I was so glad that my family and I were able to experience this.

And so what is…what’s going on here? This architects from the United States Michael Speaks talks about architecture and contemporary architects working in disposable media. Architectures that are virtual. Architectures that are temporary. And the problem that some people have with “well that’s not architecture, architecture is solid things that last.” And what this chap is saying is maybe what architecture does—and back to the pairing of information anxiety and information architecture…architecture is changing the relationships of things in space to create certain kinds of affects in how we feel. And I think Kanye changing the relationship between the performer and the audience is one of those acts of architecture that is creating emotions, creating affect. Changing his affect perhaps as a performer, and changing the experience of the audience.

So, I’m going to say that the purpose of any architecture is to ensure that the worldness of the world is systematically reinforced in the relationships which govern the thingness of things. This is a really bad translation of Heidegger. But this is what I think.

There was a different world than the typical world of audience and performer that Mr West didn’t want to live in anymore. So he invoked a new kind of world in that auditorium through changing the relationships of the things in the room. It manifested the kind of world that—a kind of world I would love to go back to. If there was a button right here, I would go— Sorry I would go right now. It was electrifying. So the situatedness of things in space as a means of concretizing the kind of world that we want to live in.

Those of you who know the proper way to set the table may become uncomfortable right now on the basis of this picture but it’s another way of illustrating the point I hope to make. This is a picture of proper protocol and etiquette in the period between World Wars I and II. So at a state dinner where French and German people were dining together, the official etiquette was changed because it was too soon for Germans and French people to have knives in their right hands. For real. The situatedness of things in space concretizes a world. And the world that French and German people wanted to live in was not a world of war. They stopped for a minute there. It was a better world.

And Mr. Heidegger explains this for us quite well. “In as much as any entity within-the-world is likewise in space its spatiality will have ontological connection with the world.” Here’s the ontology part. Richard Saul Wurman said the creative organization of information changes the meaning of information. Situating the things on the table changes the meaning of the meeting.

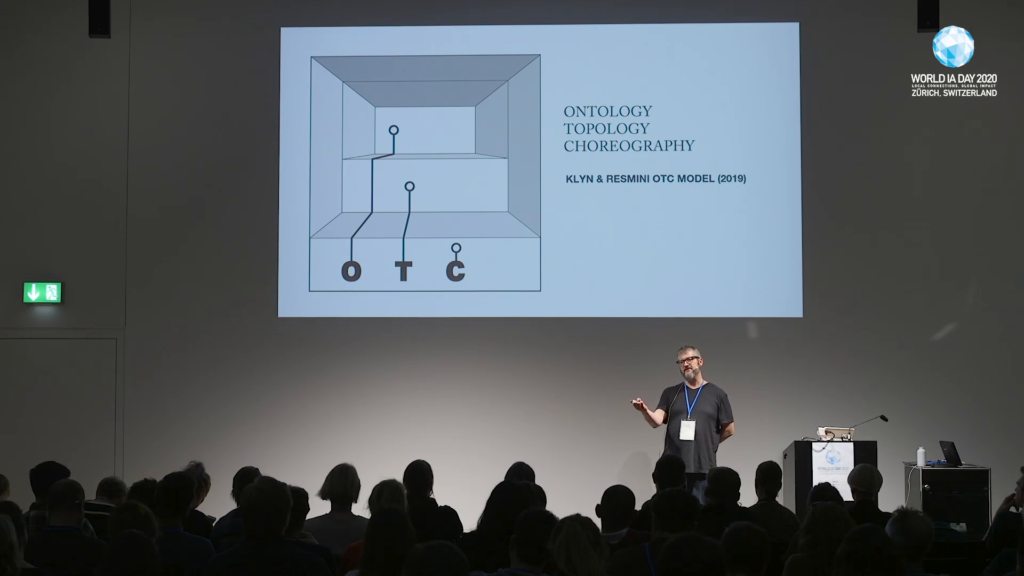

Andrea Resmini and I have developed these ideas into a theory about information architecture where ontology, what things are— The definition that we like is the science of being. So on what basis are things? There is the ontological basis. Maybe the another word for that would be “suchness.” If we were talking about bananas, the ontological reality of bananas is long yellow fruits, perhaps. The topology is the situatedness of those long yellow fruits. And if the long yellow fruits appear in the produce part of the store, then the combination of the ontology and the topology, meaning on the basis of location in space, meaning on the basis of attributes, both of those things are combining to make meaning. And then the human element is the choreography. How we interact, how we engage with the properties of things. How we intuit or understand the situatedness of things. That this all comes together into…this is what the information architecture is being generated by, ultimately, is our theory, is the interplay of what things are, how things are situated in space, and what people do.

Richard Saul Wurman is not well-liked by a lot of people. He says things like this, and that’s maybe one of the reasons why some people don’t like him all that much. That the classic pervasive seduction to designers—and he chose very specifically to not call what he does “information design.” And this is one of the reasons why. That designers, and this was observed earlier today, the obsession with problem-solving sometimes gets in the way of asking what’s true.

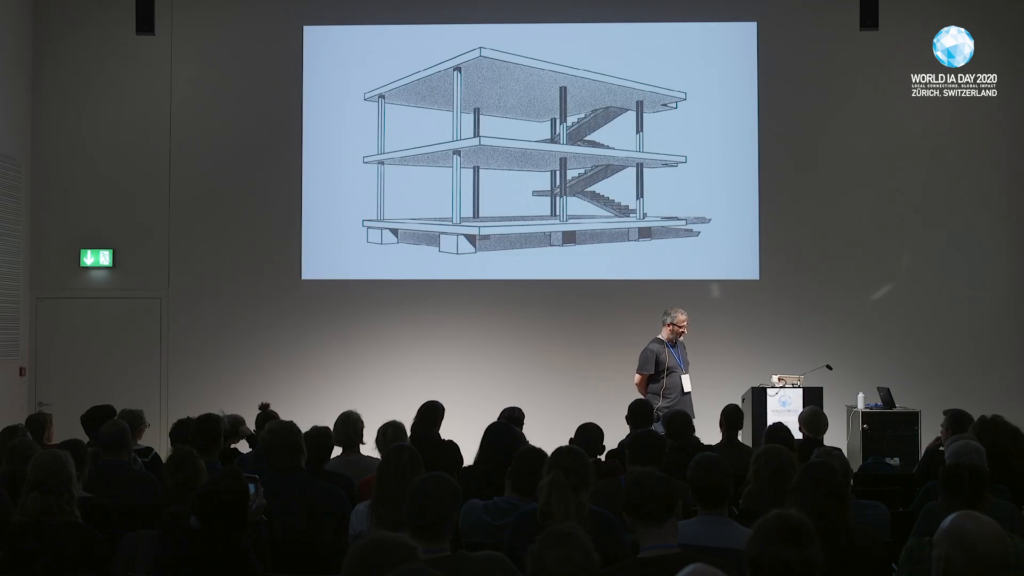

The local favorite architect, Le Corbusier, early in his career worked in a mode that is not dissimilar to this. He posited this as a generic structure that you could do anything with anywhere. And solving the problem—this is a solution looking for a problem. This is basically what started to happen generally for all of us with the Industrial Revolution, with the Crystal Palace of 1851, that surplus of means over ends. Solution before the problem.

And the different posture that Mr. Wurman prefers to take is to go backwards from the problem. And raise your hand if your clients or bosses are interested in you going backward from the problem, ever. Some of you might work in a good place. Andrea, I’m pleased for you. Anyone else feel like they have permission to go backward? Thank you. thank you.

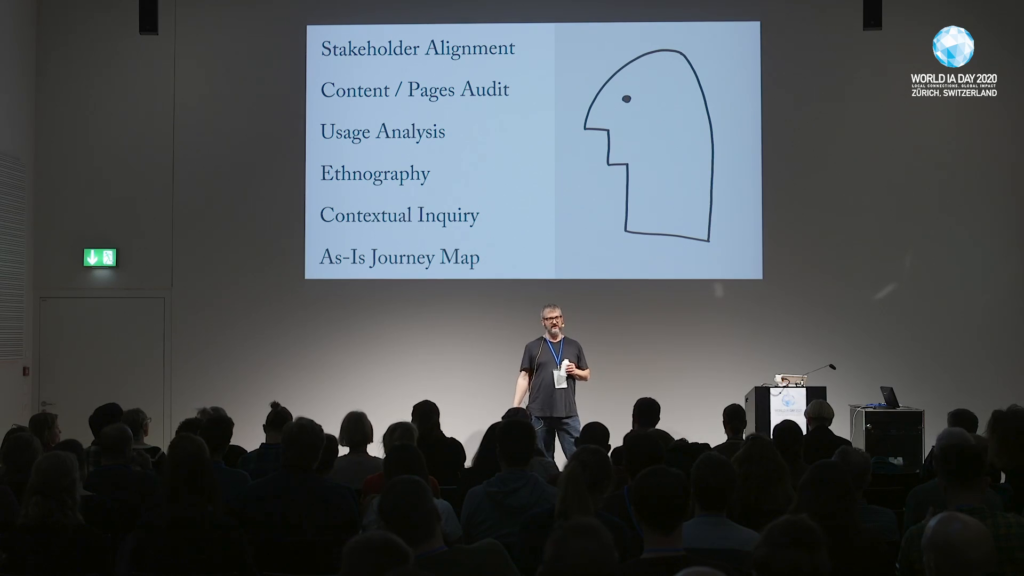

But going backward from the problem I’ve loved watching all of your presentations today. And the information architecture tools and methods that we’ve seen today, many of them are backward-facing. And the boring part. The part that many people don’t want to do. The auditing of all of the things that we’ve already done. The “what have we done” question that is certainly going to make it harder for us to deliver on that growth pattern that we’re expected to deliver on if we are looking backward and first making sure that our stakeholders are aligned. That we do an audit of all of the things. Nobody wants to— None of the clients I’ve worked with have ever had a comprehensive understanding let alone map or model of the as-is environment. In the organization, typically the attitude is “What we’ve got, it sucks. We need to do something different. What we need is in the future, and here we are in the present with all this garbage so why are you going to spend all this time and money figuring out what have we done? Can’t we just fast-forward to a better future of the sort that we would all prefer?”

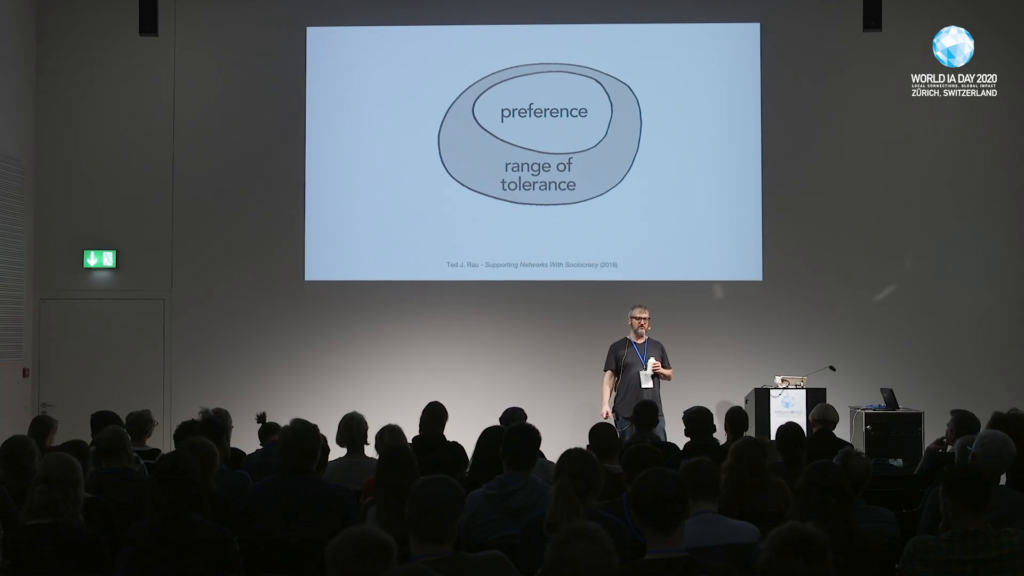

And the problem of working in terms of preference is that it’s always a smaller set of objectives than would be good. I think. So in our work with stakeholders, in our struggle as a little information architecture consultancy to win the permission from clients to go backward from the problem, we do a lot of work with stakeholders in order to get them to hold their specific preferences a little more loosely and instead to focus on their aims. And can’t we expand the zone of what is permissible, of what we will tolerate. That is one mechanism that we have found very useful to shift the focus of the stakeholder work from “What is your preference for a future that isn’t here yet?” to “Given your many often seemingly-contradictory aims, how can we expand the range of tolerance for when we do get to the solution someday where all of those aims can be balanced—they’re not all going to win—but that we can serve many aims through a broadened zone of tolerance.”

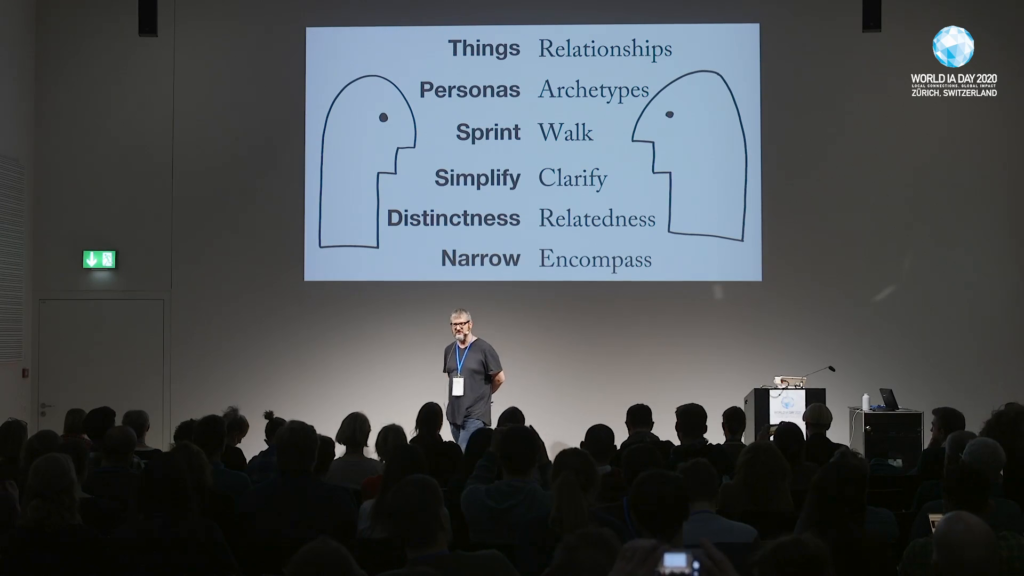

So what I’ve been guilty of in the past and that I want to leave behind is the taking of sides around this. So there are things that are helpful in the looking back, and there are necessary counterparts on the side of the looking forward. And I think we prefer Helvetica as designers, generally. And I think if we had to pick sides, who’s going to win? Well if we’re pushing that growth pattern, if that’s what we have to do, then only one side of this picture really needs to happen.

But I don’t think that that’s what we should do. I think what we need is friction. I love this quote, and this where I got the title for this talk. And it’s occurrence right now in the sequence of my remarks should be an indicator to you that I’m almost done. Perhaps it would be better to look for once in awe at what’s already here. Not with great learnedness, but with warm understanding. And I think the warmth would be generated by the friction that we create when architects and designers work together. When we resist the modality of the hand-off. Because then we wouldn’t touch, we wouldn’t get warm. I think in order to do it right…because we don’t have very many of those innovation intervals left. With climate change, with the rise of fascism. We’re almost done as a species. And so why don’t we look with awe at what we’ve got. Let’s optimize for balance.

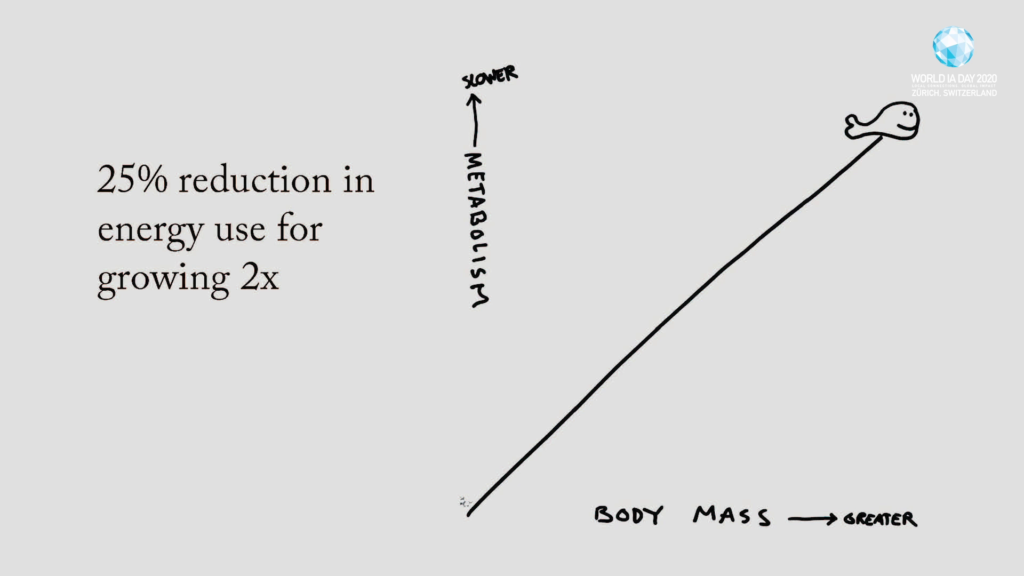

And the good news, if there is a little bit of good news—there is—is there is a different pattern. I don’t think the balanced pattern will deliver the growth of the superlinear pattern. But in his work, again using the mathematics of physics to understand the world of biology, what Geoffrey West found is that when nature builds…

You can’t see it there because it’s so small—that a mouse. And at the top end of that range is a whale. And nature can make mammals at every point along this growth curve. Because every time that nature makes something twice as big, it uses 25% less. Geoffrey West found that a mouse has the same number of heartbeats in its lifetime as a whale. And the way that nature does this is through limited growth. Sublinear growth. And as a pattern to posit instead of superlinear growth, this is a provocative and well-proven phenomenon in nature. That there is a way to keep growing. That there is a way to make a whale, to be whale. But unlike all of the whales of the works of mankind so far, these whales would be more efficient than the elephants, which are in turn more efficient than the horses, which are in turn more efficient than the cats, which are in turn more efficient— Every time you make something bigger in this pattern, you can have a reserve.

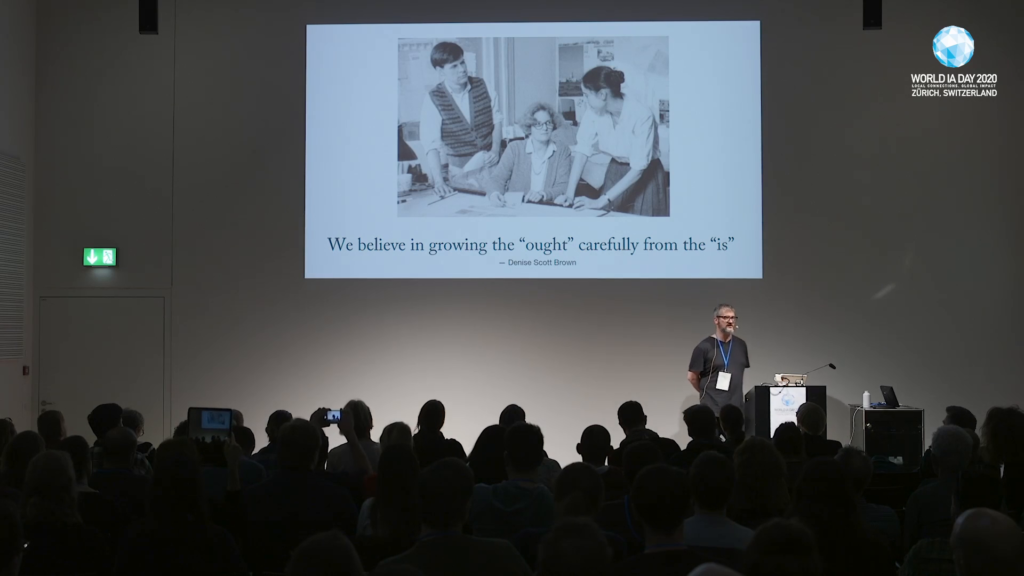

One of my favorite architects is Denise Scott Brown. She’s an AIA gold medalist in my country. And what she says—and she says “we” because she works with her husband Robert Venturi, who passed away a year or two ago. But when she says “we” that’s what she’s saying, is she and her husband, and their practice. “We believe in growing the ‘ought’ carefully from the ‘is.’ ”

So I think this is what we need to do, is to rub up against each other. The friction between what designers want, a better future, and what architects want, which is to understand the past. That together, we can have a right now that won’t kill us. Thank you.

And I think I have time for a question or two. The first person who asks me a question will get a shrink-wrapped, never-been-used paperback copy of Information Anxiety. But it’s not the hand that goes up first, it’s the person with the microphone who will ultimately decide who wins. Okay so it is the person with the hand up first.

Audience 1: Thank you for your talk. You talked about the sublinear growth. As information architects or UX designers, aren’t we involved too late in projects where actually we sort of just help materialize this growth? Because actually we would have to help them understand the concept of sublinear growth. What is your take on that?

Dan Klyn: Thank you for the question. I think… I don’t think it’s too late. And I think when we’re asked—when we… If the train has already left the station…that’s a turn of phrase in English, I don’t know if that works here. So if the train has already left the station, and if it’s on the superlinear growth track, then are we left without options. Is that a fair way of restating your question?

Audience 1: Inaudible.

Klyn: Well one thing that I will invite you to think about the next time you’re in one of those predicaments is this. [rubs the knuckles of his fists together to suggest friction] So, I am pretty conflict-averse by my personality. And when the train is already on its way, if we don’t do this it can just keep going. And so there are lots of small ways as designers that we can introduce some friction that will slow the thing down, at a minimum, if not cause it to change tracks. And one very simple way of boosting that friction to slow down the train that is headed for the trainwreck is to ask that question of what. What have we done? Look backward, bring the past into the right now. Because my sense is that our encouragement is to discard the right now and to help the organization realize something that isn’t here yet. So I think it’s like what Mr. Schwarz said. Helping the organization to look in awe, to appreciate what it is doing right now. And maybe that would have some effect.

Thanks for the question.

I usually ask my students for objections. Is anybody made uncomfortable by the things that I’ve said? Any objections? If you develop them, I’m easy to find on the Internet, so please let me know. And thank you for coming.