Hi, everyone, and thanks to the organizers for the opportunity to speak.

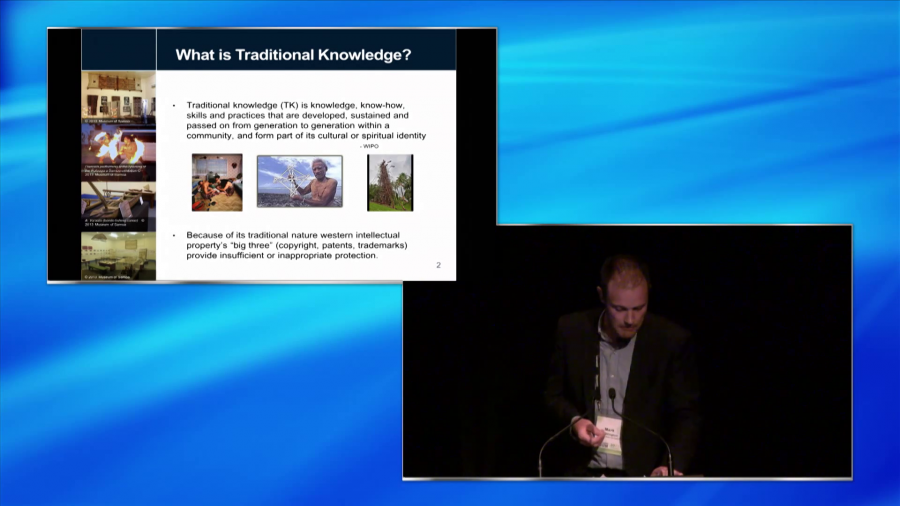

Today I’m going to talk about traditional knowledge, which is a broad concept that includes medicine, traditional know-how, rituals, dance, and art. In the Pacific, well-known examples include the Pentecost land diving of Vanuatu, the tatau of Samoa, and Marshallese sailing charts.

However, the Pacific is full of traditional cultural expressions which provide the communities that practice them with a sense of identity and continuity. In order to protect their culture from misappropriation, Pacific states have developed proposals for traditional knowledge legislation as part of national and regional initiatives.

This move to grant traditional knowledge its own category of legal protection is due to the limits of Western intellectual property law. The purpose of IP and TK protection is different, and this means applying copyright or patent protection to traditional knowledge frequently doesn’t confer the level or type of protection sought by custodians. Recognition of this has lead to the development of alternatives such as the Pacific Model Law for the Protection of Knowledge and Expressions of Culture. The Model Law means that despite differences between Pacific countries, there’s a degree of uniformity to national approaches. On this basis, I’m going to use one recent proposal to illustrate issues of access and digitization.

Samoa’s draft proposal to adopt traditional knowledge legislation recommends establishing a new legal framework which grants automatic protection for Samoa’s traditional knowledge in perpetuity, provided that the expression is maintained by the traditional community. Unless prior informed consent is given by custodians, traditional knowledge use in non-customary contexts is prohibited, and this includes any reproduction or recording of traditional knowledge, or facilitating access to cultural expressions online.

Management of traditional holder’s rights will be overseen by a body made up of representatives of public authorities, community, and experts in relevant fields. This authority will function as a contact point for potential users of Samoa’s traditional knowledge, it will maintain a knowledge database, and will also promote public awareness of traditional knowledge issues.

So what would this mean for those with an interest in digitization? Despite being a new legal framework, the proposal may lead to some familiar problems for cultural heritage institutions. Many of you are aware of the problem of orphan works in copyright. This is where the owner of a protected work is unidentifiable or uncontactable, and because they can’t be found it follows that they can’t grant permission to others to copy their work. The proposed legislation will create similar frustration. I thought I’d illustrate this with an example.

Suppose you find in Samoa’s national archive an example of traditional knowledge documented by the German-Samoa administration circa 1909. This letter details medicinal qualities of specific indigenous plants, but it doesn’t reference the traditional custodians and the traditional knowledge in question doesn’t feature in the authority’s database. You want to digitize the letter for purposes of access, but you don’t want to break Samoa’s law in the process. How do you determine whether this traditional knowledge is still protected if protection is tied to practice by a non-custodian? Moreover, what if there is the suggestion that this information is of a secretive and highly-prized nature? How do you go about finding the custodian without disclosing the traditional knowledge?

To reiterate, the draft proposal automatically protects all of Samoa’s traditional knowledge, and while registration is encouraged it is irrelevant to the issue of legal protection. This puts the prospective digitizer in a difficult position. They’re reliant on the authority’s records to gain consent and establish what appropriate use is, but they cannot assume that traditional knowledge is free to use just because it doesn’t feature in the database. By digitizing unreferenced material, they may be acting contrary to law. Meanwhile of course, documentary heritage risks being lost before it can be preserved.

So what can be done to overcome this problem? Museums and archives could encourage the registration of traditional knowledge. However, custodians may be reluctant to disclose closely-guarded traditional knowledge to a state authority. Tensions do exist between traditional custodians and the Samoan government on preservation issues, and mistrust may hamper the goals of the legislation. It’s also important to bear in mind that there’s little incentive to register traditional knowledge if the protection already exists.

A second option is to encourage the inclusion of digitization exceptions to the proposed legislation. The report does recommend establishing exceptions to promote the development of culture in the public interest. But exceptions are likely to be interpreted extremely narrowly and be subject to the acknowledgement of origins, which of course is problematic in the forementioned example.

That aside, this law is very necessary, and I want to conclude on a more positive note by discussing what the proposed traditional knowledge legislation means for cultural institutions in the region.

Although the law will only apply in Samoa, the establishment of the traditional knowledge authority, and the guidance it can impart, will benefit responsible digitization of Samoan content internationally. To date, museums and archives have relied on advice to best practice from experts in the field. Guidance from the traditional knowledge authority, acting on behalf of the villages and families who are custodians will further ensure online access that is respectful and in accordance with traditional communities’ wishes.

Cheers.

Further Reference

Copyright Law and the Digitisation of Cultural Heritage, with Susan Corbett