Rachel Kalmar: It is my great pleasure today to introduce our speaker An Xiao Mina, who will be talking not about the Internet of Things but rather the things that emerge from the Internet. An is a technologist and researcher and fellow fellow at the Berkman Klein Center. She leads the product team at Meedan, which builds tools for global journalism. An is also working on a book about the topics that she’s going to be discussing today, on Internet memes and social movements, which is going be published by Beacon Press.

Now, I’ve had the opportunity to get to know An over the last year at the Berkman Klein Center through the Hardware Working Group, which An and I together with Jason Griffey started. We also have the distinction of spanning fifteen timezones, which is a challenge that is known by all people who produce things in Shenzhen. So that’s our own little taste of it.

My own research is about the Internet of Things, and so it’s been really interesting hearing and learning about An’s perspective, which is not about just the technology but more about how ideas on the Internet can turn into physical objects and how this process is shaped by people and by social movements. I’m excited to hear more about this today. Please join me in welcoming An.

An Xiao Mina: Thank you so much Rachel for the kind introduction. Thank you everyone for coming to this talk. I’m excited to speak here because I became acquainted with the Berkman Klein community about four years ago when I spoke at ROFLCon 3—Rolling On the Floor Laughing Con—on a panel that Ethan Zuckerman hosted about Internet meme culture globally. And this talk today is kind of an extension and evolution of some of the research that I presented there, and is looking at some new trends around object culture and its intersection with Internet culture.

So, I’m going to be talking about hats, if that’s not obvious from this photo. But I also want to clarify the hats I’m wearing today—the metaphorical hats. I’m a product manager so I think about products and how products enter the world and how they influence the world and reach new audiences and users. And I also look at Internet culture and how that intersects with social movements. I’m interested in kind of the social power of the Internet and some of its drawbacks as well. And I’m also a little bit of a photographer, so many of the photos here are photos that I’ve taken in different contexts around the United States and in China. And as I speak I encourage you to ask questions. We’ll have time afterward for Q&A, but also feel free to just raise your hand and jump in if you have questions.

I’ll talking about two seemingly very different contexts, one of which is political culture in the United States in the past few months, as evidenced by this photo. And then I’m going to jump to Shenzhen in China, Southern China, to talk a little bit about commercial production culture over there. And I’m going to try to weave together some threads and themes, and talk a little bit about the mechanics of object production as it meets networked culture.

So I want to start with the Women’s March from just a few months back, and subsequent marches and protests that’ve happened since then. From afar it’s always a very visually striking movement. You can always see a lot of signs, you can see a plethora of pink hats. And I think what’s interesting here is when you start to zoom in and you see how those signs are structured and how they’re often intersecting with the Internet. It’s very much a networked sort of protest in terms of its aesthetics and media.

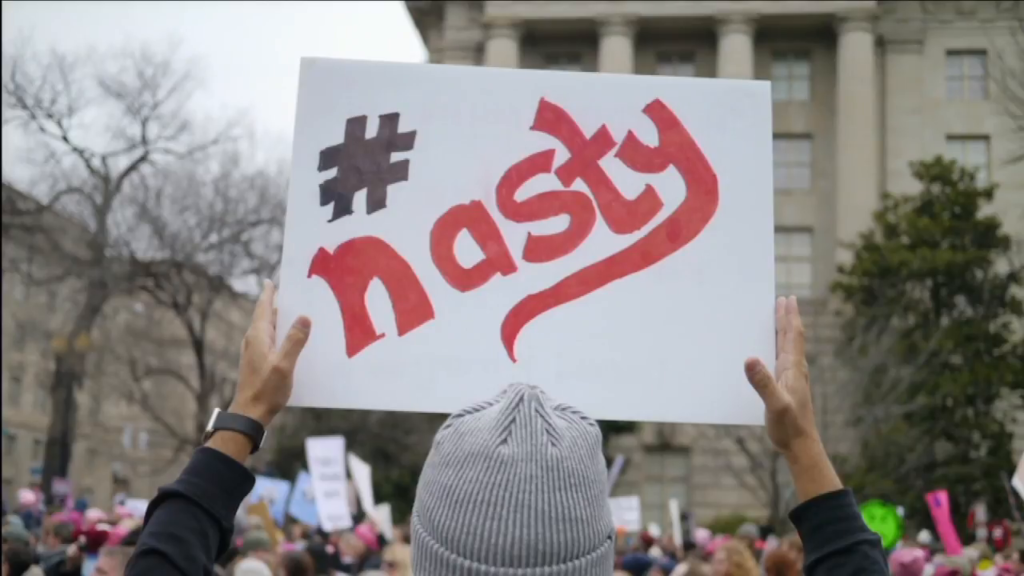

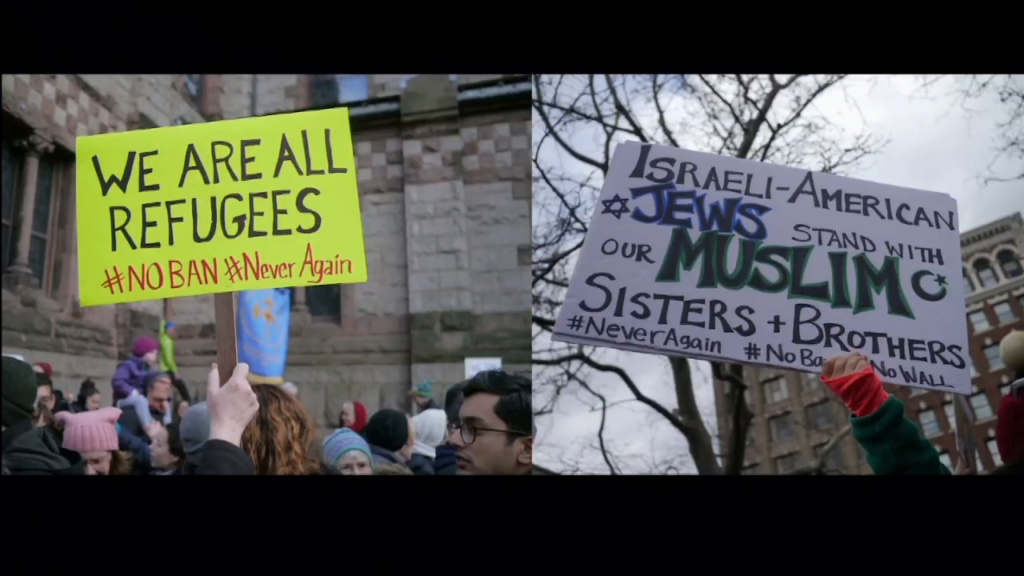

Over the past few years we’ve seen the emergence of hashtags, these kind of digital artifacts popping up on protest signs, from #BlackLivesMatter to #nasty, referencing the hashtag #nastywoman that popped up after the third Presidential debate. These hashtags are very interesting to me because it’s a digital artifact that then gets expressed into the physical sign. And why people do that is an open question and something I’m interested in talking about.

That hashtag is kind of central to the sign, and these hashtags are starting to behave very similar to how we see hashtags on Twitter and Instagram posts, where they’re kind of tying together different signs where the main theme is semantically very different, but then you have these hashtags that tie together those signs in the same way that digital hashtags might connect Instagram posts and tweets. But here it’s happening in the physical world.

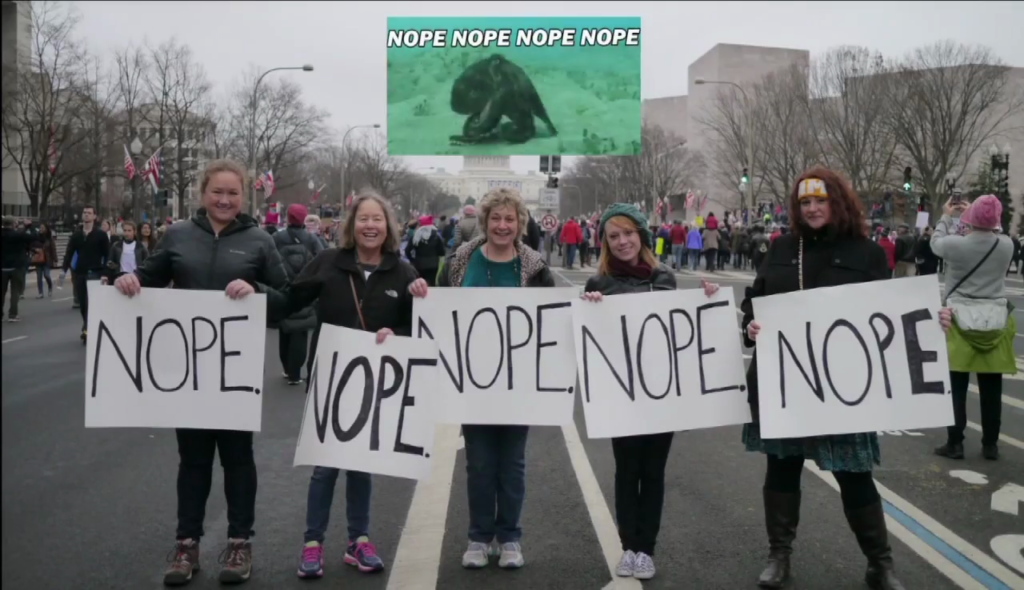

And then you have other sorts of digital artifacts popping up, specifically Internet memes. The “nope nope nope” octopus has popped up in a number of signs, with these “nope nope nope” signs, which are very common in different protests.

You have the honey badger doesn’t care; this time the honey badger does care, and this a printout of that same honey badger meme.

And then the “This is fine” dog, which became very popular in 2016 also popping up on signs. And so you’re starting to see the emergence of kind of Internet meme culture inside the physical signs, which are then photographed—they’re they’re designed to be photographed—and then pushed back online, where they enter the Internet meme vernacular.

The hashtag #WhyIMarch was a popular hashtag during the March, and there are a number of people like this woman who was encouraging people to actually write on the sign why they march. And she was really riffing off the social media support kit of the Women’s March, which had encouraged people to use the hashtag to indicate why they want to march. And so here again you have a digital practice placed onto the physical sign, and then people were taking pictures of that sign, putting it back online, back on the hashtag. So it became part of the Internet vernacular, even though it was happening in physical space.

April Daniels on Twitter, 11/15/2016

Let’s dive into one of these kind of viral media. This is one of the more popular tweets that emerged after the elections, that came from progressive circles. And so this tweet from April Daniels as you can see got 14,000 retweets, really resonated with a lot of people.

Desusnice on Instagram, 1/29/2017

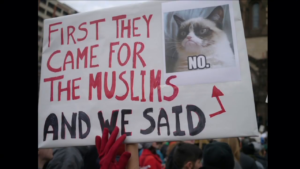

And then during the Muslim ban protests a few months ago, that same tweet started showing up on signs. Because it had gone so viral, it started to show up on different signs. And this is one that was in Los Angeles I believe, and then it was then posted on Instagram and then once again entered the kind of circulation on the Internet.

These are photographs that I took of variations of that. People were remixing that with—this is obviously Grumpy Cat. The reason she had included Grumpy Cat was so she could have a conversation with her children without using the punch line for the original tweet.

And then of course also variations where people have modified that, and this is in Copley square in Boston.

And so what we’re seeing today is protest signs have as their audience and source of inspiration both the physical crowd around them, which is what traditionally protest signs have done; the wider Internet—the Internet where people are looking at pictures of these signs; and then all the other protests as well. And what we’re seeing is an emergence of kind of a shared visual and verbal vocabulary of protest signs and other objects that pop up around national protests and increasingly in international protests in many Western contexts.

And I included this one because this is kind of an indicator of that new relationship with the network, because many signs now have words on the back as well. Because there’s no longer this relationship or assumption that the photographer will be in front of you but also might be part of the crowd and therefore taking pictures and therefore maybe might be posting things online.

Anyone who’s been to these marches knows that there are also a number of hats that’ve been popping up. And this is a picture I took at the Women’s March, because it was right after inauguration day, of two types of hats. And it was very apparent to me when I entered Union Station to see pink hats and red hats, and very much the association with these two hats is one of people coming for the coming for the Women’s March, and one of people coming for the inauguration day.

And so I want to zoom in on the ones on the left first. These are the pink pussyhats. This is the Pussyhat Project, started really [as] the brainchild of Krista Suh in Los Angeles and became part of a project with the Little Knittery in Los Angeles.

And I’m going to ask if we could start passing out— I actually brought some of the pink pussyhats. And start looking at them, because from afar they all look very similar. You see the sea of pink heads. But in detail they’re actually quite different. And the way the project worked was the Pussyhat Project distributed patterns online that encouraged people to to make these kind of pussyhat designs, these pink yarn designs. And then they prefigured that with an illustration of what that might look like at the March, to really inspire people. And this happened about two months before the March, and people start getting together in knitting circles.

And instead of following the pattern word for word or kind of script by script, instead by people made variations of that. And what I want to argue today is that part of these hats—these physical hats are actually following Internet meme culture and the norms of Internet memes. And as you look at them, I’ll start tying that together.

But take a look at some of the these hats and these variations. These are all variations from DC. Here’s a black one with the rainbow flag. These are from Maryland. And you can see on the sign different colors beyond pink. And then this is one from Boston. This is pussyhat screenprints in Oakland.

So people are taking the basic idea, the basic kernel of it, but often remixing it. And as you’re looking at these you can see in detail that there’s actually quite a bit of variation.

And there’s a loom passed around from Berkman’s own Carey Andersen, because she also made some as well and used a loom instead of the handmade instructions. So people often reinterpreted the hat to their own skills and interests.

Images (left, right) p_ssyhatproject on Instagram

Using Your Feminist Superpower: An Interview with the Pussyhat Project

And that was kind of the point. The point of the project was that it was networked. These are pictures from the Instagram account for the Pussyhat Project. And the whole goal here was that the hats were designed so that people who could not attend physically would make the hat. They would send it to someone who was able to attend. That person who attended would then take a picture of themselves with the hat, and send that back to the maker. And so the whole point of this was that it was digital, it was networked, and it was participatory in a way that combined both the physical and the digital.

I suggest defining an internet meme as

(a) a group of digital items sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance;

(b) that were created with awareness of each other; and

(c) were circulated, imitated, and transformed via the internet by multiple users.

Limor Shifman, A Meme is a Terrible Thing to Waste: An Interview with Limor Shifman (Part One) [presentation slide]

So what I’m talking about today is that I think these these hats, these signs, and these other objects that I’ll be talking about today are part of Internet meme culture in a different way than we traditionally think about objects. So when I talk about Internet meme, I want to make a distinction between the kind of Dawkins sense of meme, which is the notion of the cultural unit, and the kind of notion of the Internet meme.

Limor Shifman has written about this, and it helps us make a distinction between between—you know, the word “Internet meme” has kind of emerged in the culture of the Internet as this kind of unique practice, so this thing on the Internet that happens that’s kind of diverged—like a meme—from the original Dawkins sense of meme. So when I’m talking about meme today, when I’m talking about memetics, I’m typically talking about Internet memes specifically.

And so Shifman’s definition of memes is a useful one that I tend to agree with, that helps us think a little bit about what’s going on with these hats and these signs. So, an Internet meme is a group of digital objects that share a common stance, form, and content. And so you have these kind of shared characteristics, where there’s a Platonic form but no one is alike. They’re created with awareness of each other, so there’s this kind of social component to it. And then they’re circulated, imitated, and transformed via the Internet by multiple users.

This last part is really important because this notion of transformation and multiplicity is what makes an Internet meme different from a viral object, at least within the definition that I’m talking about today. Because a viral object might be like the Old Spice video that is shared frequently and is looked at and viewed, but doesn’t have this notion of transformation. Whereas as a video like the “Gangnam Style” video, where people are dancing along creating their own videos is closer to what an Internet meme is, at least in this definition.

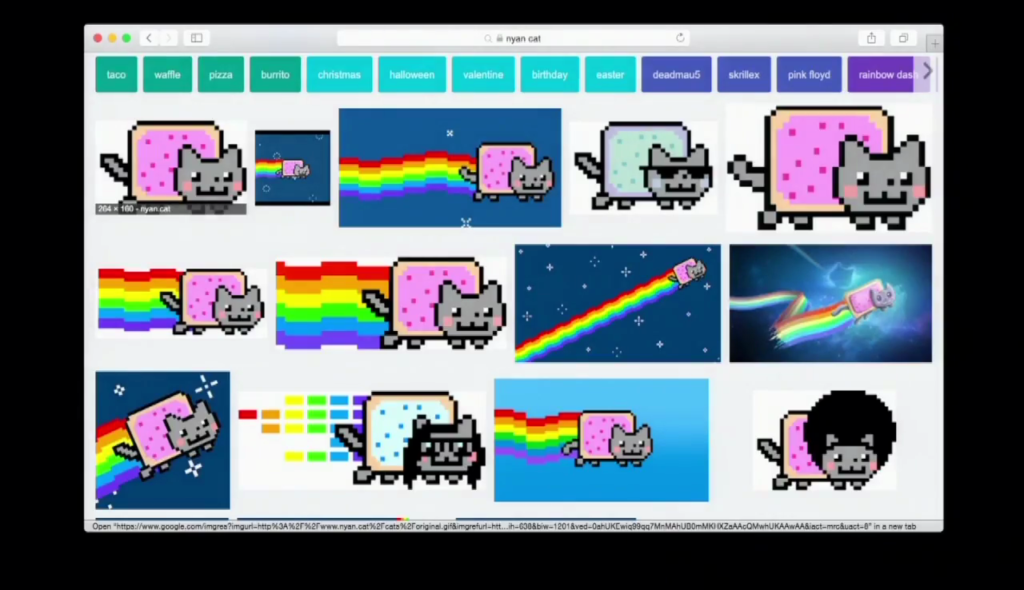

So the classic example of course is the Nyan Cat. And you’re looking at the Nyan Cat, it has common characteristics of form, there are multiple people creating versions of this, they’re following the 8‑bit format and this idea of a cat with a Pop Tart, but often remixing and reshaping it based on their perspectives, their interests, or contributions.

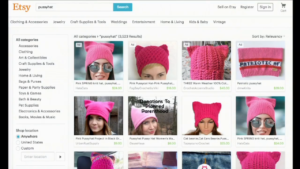

And in many ways, the pussyhats follow the same formats, right. And in many ways it’s as much digital when you look Etsy, look on Google Shopping… Look on any web site and just Google “pussyhat,” you will see that wide variety of variation, just like you do with digital memes.

And I think this is intentional. I think this is people aware of the fact that they’ll be photographed, the fact that these images will be circulated online, and that their contribution will be part of the shared a visual language around protest in the United

States.

Now, there’s often a contrast drawn between—and especially on the weekend of the Women’s March—between the hand-knit pink hats and then the red Make America Great Again merchandise that was perceived to be mass-produced.

And again, from afar it looked like that, right. You see pink hats, you see red hats. But as you dig deeper you see that these kind of mass-produced objects also have this notion of remix and multiplicity that we associate with Internet meme culture, and as I argue here with object meme culture as well.

These are other photos that I took during the Women’s March. This is a man who’s wearing a red hat that he had remixed because he was campaigning for transgender equality in North Carolina. And so remixed the red hat to reclaim the notion of the red hat for his political cause.

Other hats included “WTF America.” This woman had the Unitarian Universalist principles on her hat. Our own Ethan Zuckerman made a remix; this is “Make America Kind Again”

And if we could start passing around the red hats—I think those are circulating now—some of the red hats circulating include this one from Jeronima Saldaña who’s an activists/artist who who created all these remixes in response to key phrases and things that had been circulating online. And you can see those hats, and you see how they’re made. They all take the form but then they remix it, they modify it.

It’s a very different process of course from the knitted hats, which rely on hand production, and I’ll walk through how those are made. But the spirit of this is the same, is that with digital objects we’re used to the idea that they never stay still. And now we’re starting to see this with certain a class of physical objects as well.

And I would argue also part of the effectiveness of the hat, if you look at Jeronimo’s profile picture, is that this becomes a political indicator, a declaration of political allegiance through selfie culture. So once again the hat is physical but it’s also digital. In the same way that screen overlays for marriage equality had been a way to indicate political allegiance, now you have hats as well. And that’s part of the effectiveness of the red hats.

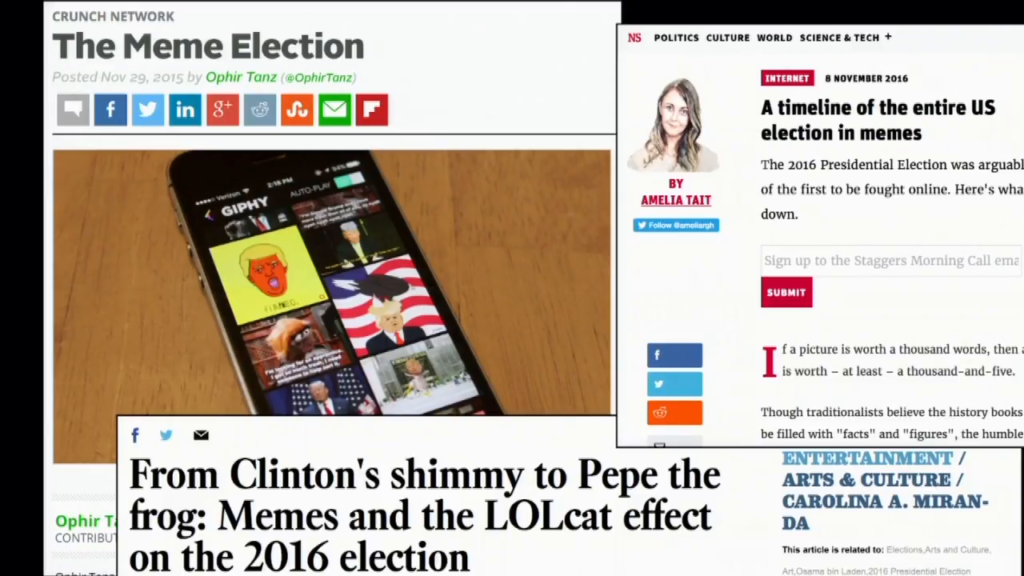

The Meme Election, TechCrunch; From Clinton’s shimmy to Pepe the frog: Memes and the LOLcat effect on the 2016 election, LA Times; A timeline of the entire US election in memes, New Statesman

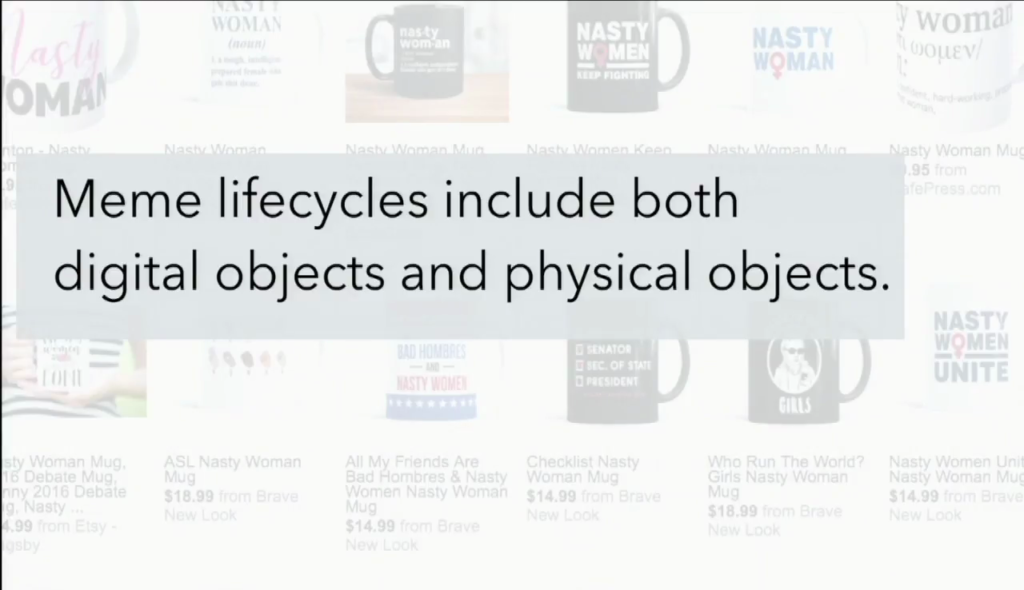

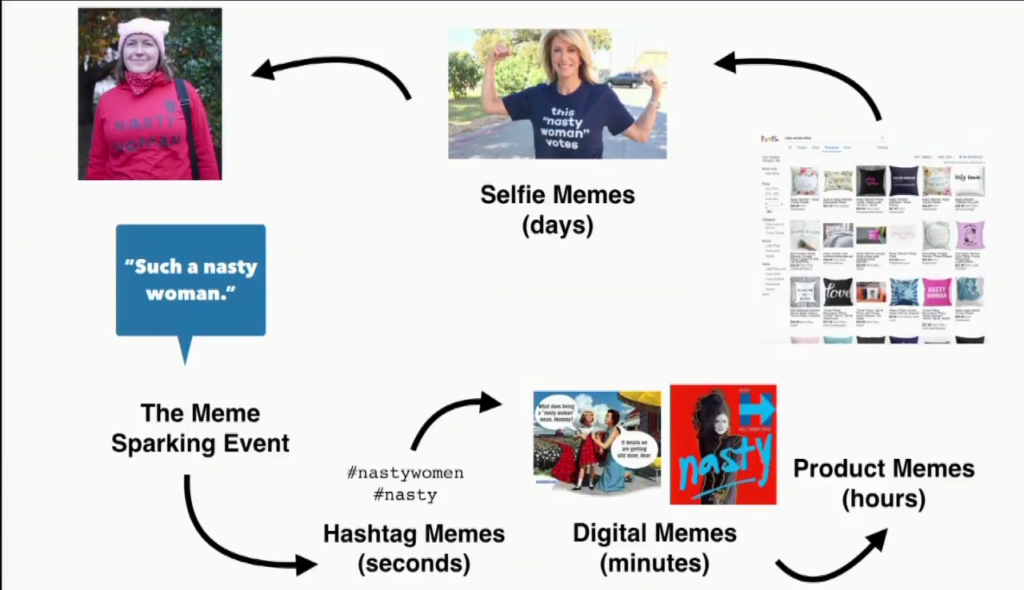

So, 2016 was known as the meme election. I think a lot of people were observing this. I’m sure many of us were observing the number of memes that were popping up. But I think what was missing from this conversation was this notion that meme lifecycles now include both digital objects, and increasingly, physical objects.

And let’s take a look at what I mean by that. You can see in the background some of the “nasty woman” mugs.

So remember during the third presidential debate when the Republican candidate called the Democratic candidate “such a nasty woman.” I’m sure many of us remember this moment. Within seconds, people responded. They created a hashtag, #nastywoman, #nasty, as a way of reclaiming that phrase as a source of power rather than an insult.

Within minutes of that, there were digital ones. People remixed the Janet Jackson album Nasty to include Hillary Clinton’s face. There were comics of these. We’re used to this kind of thing happening now. This is the meme election.

But what was interesting to me was the product meme that popped up after that. If you search on Google Shopping for nasty woman pillow, nasty woman cloth bag, nasty woman hat, nasty woman mug, nasty woman pin, nasty woman sticker… Think about any product and put “nasty woman,” you’ll probably find that product. And you’ll probably find endless variations of that product, in much the same way that the digital memes were circulating.

Those memes then, as they shift, they became part of selfie memes. This is a photo from a fundraiser for the Texas Democrats. And then they circulate, they circulate, they go back online, and again this kind of intersection between the digital and the physical with objects are just as memetic as the digital objects. The physical objects are just as memetic as the digital objects.

And so I argue we should extend our understanding of Internet memes to include physical objects as well. A certain class of physical objects, not yet nasty woman, computers, or cars—or maybe there are, I’m not sure. But for a certain class physical objects, you have this notion of remixing almost as quickly as digital objects.

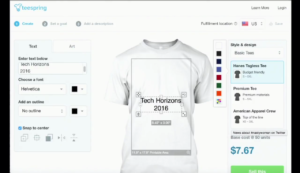

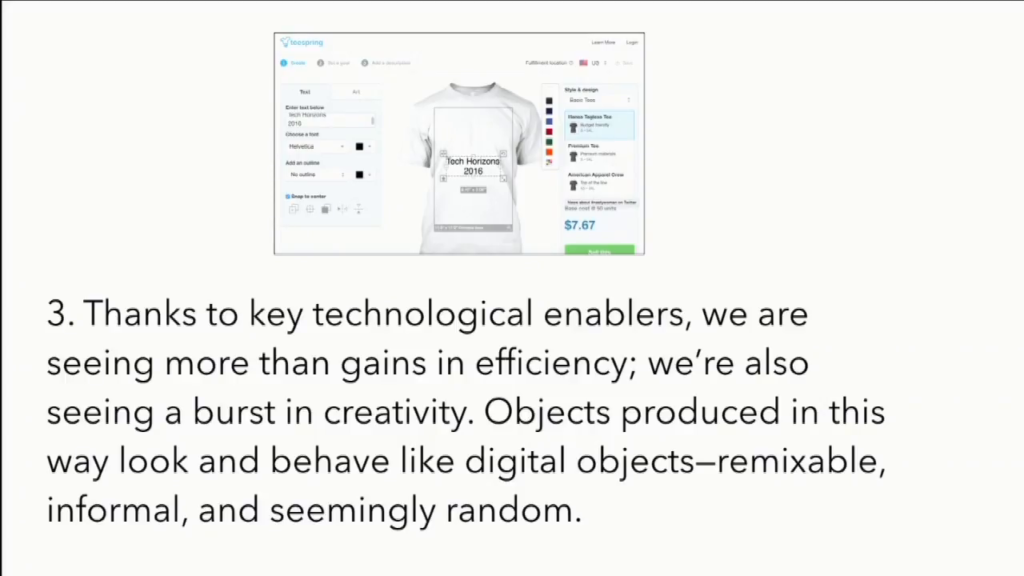

None of this is a surprise or an accident. Since 2008—the Facebook election—the meme election has seen a wellspring of technological developments that have made it easy for us to quickly adapt a t‑shirt for any idea that we have on the Internet. So it’s easy for us to slap on on text, a logo, a digital meme, and put that on t‑shirt, indicate a price, and then do some fundraising around that. And then you can get the matching mug as well.

Sites like Teespring, Vistaprint, let you order just one hat of a kind. So if you really feel passionate about that hashtag you could just get one for yourself.

CustomInk, there’s a hat floating around from CustomInk. Allows you to do this for all kinds of products. They really streamline that process so that it’s much simpler to take your idea into a physical object in the same way that Photoshop has done for images.

April Daniels on Twitter, 2/1/2017

And if we follow the path of April Daniels’ tweets, she got so much response from November out for her tweet that she then went on to Teespring, created a shirt using that tweet, and then created a fundraiser for the ACLU.

It should be as easy to bring a product to market as it is to have a great idea. The best ideas should win, not just the ones with access to capital.

Walker Williams, “These Guys Made a T‑Shirt. Now Silicon Valley Is Giving Them Millions” [presentation slide]

This is all deliberate. Walker Williams, the founder of Teespring, in an interview noted that the goal here, the goal of the site, is to bring a product to market as quickly as possible. To take care of the production, the logistics of shipping, the logistics of printing, so that all you have to do is have the idea and so you can get your audience as quickly as possible. So it streamlines this process. This is why it’s just as easy—almost as easy—to type a hashtag as it is to make a t‑shirt with that hashtag. Because you have tools and processes that make that simple.

So I’m going to transition now to China. And I want you to hold this thought about this idea of outsourcing a project, and outsourcing sort of the tools and the ability to create formerly complex products, and start thinking about this in other contexts—in the commercial context.

So I want to take you to Shenzhen. Shenzhen is a small city of twelve million people in the Pearl River Delta. If something is made in China, it’s probably made in the Pearl River Delta. And if that something is hardware, it’s probably made in Shenzhen. This is a region of the world typically known as the world’s factory, where the stereotypes of “Made in China,” cheap products, copycat goods, things like, are popping up and being shipped around the world.

This infrastructure has also given birth to a new type of object production, known as shanzhai. And I’ll talk about shanzhai, and I apologize to the non-Chinese speakers, but Shenzhen and shanzhai have nothing to do—they’re not related etymologically, although they sound very similar. But shanzhai production is endemic to Shenzhen.

Shenzhen, China, a Silicon Valley of hardware, Financial Times; The Changing Face of Shenzhen, the World’s Gadget Factory, Motherboard; Shenzhen: The Silicon Valley of hardware, Wired UK

What we’re seeing right now is a shift in narrative about Shenzhen from made in China to created in China. And in the Western world, the narrative is shifting [to] Shenzhen as the Silicon Valley of hardware. How many of you have heard that phrase, Shenzhen is the Silicon Valley of hardware? It’s starting to emerge, yeah. It’s starting to become more familiar as the narratives around what is made in China, how things are made in China, is starting to shift.

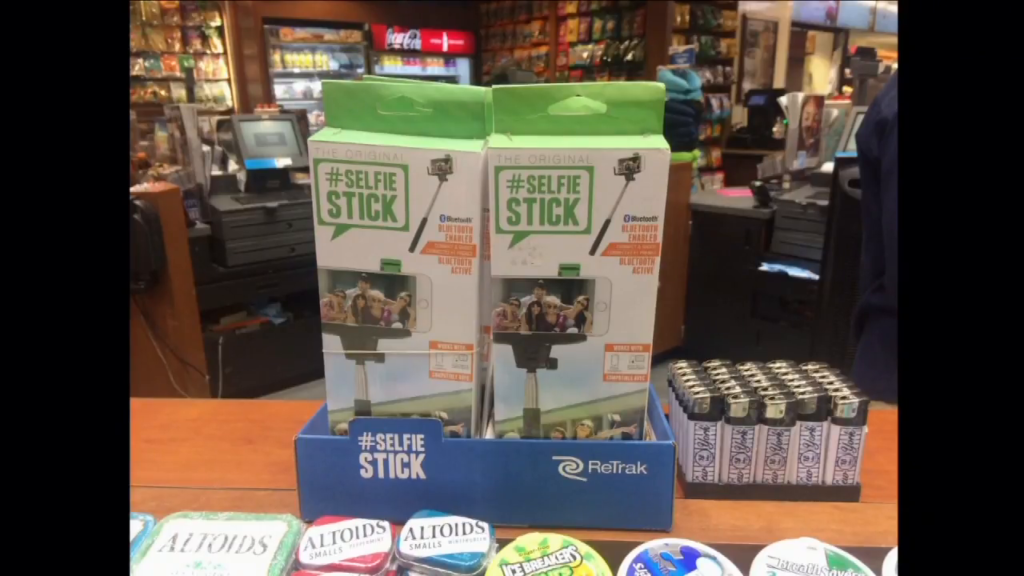

But what interested me was— At one point I was interested in kind of Silicon Valley practices entering Shenzhen. But I was also interested in selfie sticks. And I’ll talk a little bit about why that is. But let me define shanzhai for you really quickly. Shanzhai means “mountain bandit,” and it’s typically translated as “bootleg” but in many cases it’s actually a form of open production that very much looks very similar to the hat production, to the yarn production, where many people are producing objects using raw materials.

And so if I can ask if we can start passing around the selfie sticks. I brought a bunch of selfie sticks from Shenzhen. And again, from afar they all look the same, but as you look closer you start to see these characteristics, these common characters of form, style, stance. And I’ll talk a little bit about how this open community of production is now intersecting with the Internet.

So for those of who don’t have selfie sticks in your hands, here’s some photos I’ve taken from around the world. This is from New York. This is from Paris; sorry it’s a little dark. This is from Spain.

These are from China. And the selfie sick is itself an iteration, it’s itself a remix of the culture of producing tripods. And so you remove the tripod base, and then you get a selfie stick. And so this is really the evolution of the selfie stick, in the form of iteration. There is no one selfie stick. There is no one producer of selfie sticks. There’s no one factory of selfie sticks. There’s no one shipper of selfie sticks. It’s a highly multiply-produced and distributed product. And yet somehow it went global and became a global product very quickly.

And there are a ton of variations. There’s ones with mirrors— [To audience:] Yes.

Audience 1: [Question inaudible]

Mina: There is, actually, and we can talk about that, actually. So let’s hold on to that note.

There are selfie sticks with Bluetooth triggers. This is a selfie stick that has no trigger because it comes with an app that detects when you are doing the peace sign, which is a common sign that Asians use when getting a picture taken, and it automatically takes your picture.

There’s a tiny selfie stick. Their are mid-size self sticks. All of these selfie sticks are in this wide variety of variation. And so when we’re talking about patents, for instance, the question of course is then which selfie stick is patented and to what extent are variations covered by that patent or not? And so it’s an open question.

By working together, the at first small but quickly expanding network of producers, designers, entrepreneurs, engineers, vendors, and traders was able to compete with the large contract manufacturers and their international clients, reaching emergent global markets previously untapped by Western IT giants.

Seyram Avle and Silvia Lindtner, Design(ing) ‘Here’ and ‘There’: Tech Entrepreneurs, Global Markets, and Reflexivity in Design Processes [presentation slide]

The way that shanzhai works, this is a great description from Silvia Lindtner and Seyram Avle, who wrote about shanzhai, is that it’s a networked process. It’s very much bottom-up production rather than top-down supply chain management. What that means is that a small but quickly-expanding network of producers, designers, entrepreneurs, engineers, vendors, and traders are working in a networked way to compete in the global markets, and typically in Global South markets, to create products that people people want but typically don’t have access to from kind of top-down supply chain management companies. And so shanzhai is very much a networked process within Shenzhen—Shenzhen the city not shanzhai the production process.

Shenzhen the city, you have stores where you can buy the raw parts to make electronics. You can also buy the electronics themselves. The shanzhai ecosystem has created miniature phones, it’s created Bluetooth karaoke mics for your smartphone. And these are phones that were exhibited at the V&A Museum exhibition in the Shenzhen Biennale. And these phones were again a remix of existing phones but with larger buttons, so that elderly people or people with visual impairments could actually read the buttons.

And so our narratives about products that come out of Shenzhen as copycats really need to shift to start thinking about this notion of remix. That there’s a base product that people are often riffing off of, and then making variations that didn’t exist before. [To audience:] Yes.

Audience 2: You put your own brand on that, and sell it.

Mina: Yeah, that’s right. That’s a great point. So what we’re seeing here is an example of white-label production. So in that notion of brand it’s very similar to the hats, actually, where you can order these phones online and then place a brand or brand identity or logo, similar to the hats and how the hats work. And so these adaptations are very much designed for people to come from the Internet to say, “Okay, I want these sort of phones. I’m going to slap a logo on it and then create that.” And so it’s a good example of white-label production as well.

Products are market-tested directly by throwing small batches of several thousand pieces into the market. If there is demand and they sell quickly, more will be produced. If the market demands something else, alterations to the functionality and design will be made. Here, prototyping and consumer testing occur rapidly and alongside the manufacturing iteration process, rather than occurring beforehand (where it is commonly placed in Western-centric, primarily Silicon Valley type design models).

Silvia Lindtner, Hacking in Shenzhen interview [presentation slide]

So the way shanzhai works is very similar to how digital content works. And if anyone’s ever tested headlines for journalism articles, in journalism people will often test ten different headlines, throw them all out, see which ones get resonance, and then pick the one that gets the most likes and clicks and then amplify that one.

Shanzhai works in a very similar way to digital content in that regard. Products are market-tested directly by throwing small batches of several thousand pieces into the market. You can imagine the first selfie sticks, people weren’t sure if those would actually reach market saturation or market interest. And so they would just throw out a few hundred and see what happened, and then see if people responded and wanted to buy some.

And then here, it’s actually a very different process from how Silicon Valley typically works. Here prototyping and consumer testing occur rapidly and alongside the manufacturing iteration process. So as you’re throwing things out, as with those headlines, as with digital content, you’re also getting feedback immediately from buyers. And so that’s how shanzhai works. It’s very much an open system.

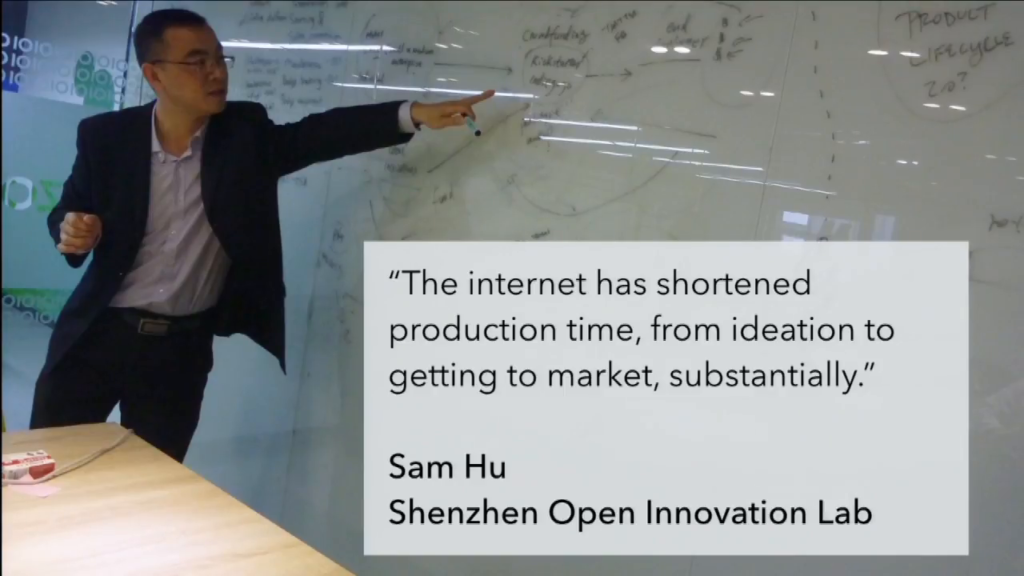

And this was really before the Internet started to take hold in China. And so as the Internet is connecting with this kind of open network system, we’re starting to see that the Internet is in many different ways shortening production time. I did a workshop with Sam Hu at the Shenzhen Open Innovation Lab, which was founded by David Li, who’s a friend of Berkman and an adviser at the Digital Asia Hub. And there they’re really studying different styles of open innovation. They look different from our typical definitions in the West about what innovation looks like.

And so what Sam was really arguing as we did this workshop is that the Internet is shortening production time. Typically in Shenzhen with the shanzhai ecosystem, a phone can be built in twenty-six days. A new phone can be built in twenty-six days. And Sam was arguing that that can be dramatically shortened to sometimes as short as two weeks, but probably a little bit longer than that. But in any case, we’re seeing increases in efficiency.

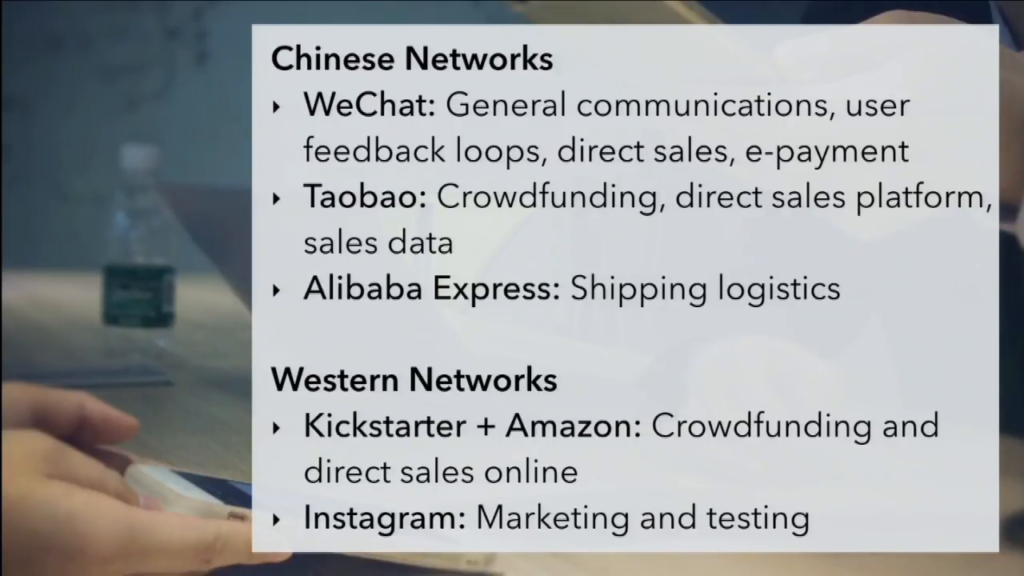

And to break that down a little bit, these are few examples of what that might look like. So WeChat—how many of you are familiar with WeChat? Chinese language social network, kind of resembles WhatsApp or Facebook. It’s allowed for people to directly communicate with their factory, regardless of where they are. Importantly, it’s allowed for user feedback loops, so that users of selfie sticks or other products can have direct interaction and contributions with the designers and makers. So you have a tighter feedback loop so people can make those quick integrations that I was just talking about. You have direct sales and epayment. And epayment is really important because it means you don’t even have to leave your house to buy a new product.

Taobao about is another site. How many of you are familiar with Taobao? It’s kind of an eBay-like platform, yeah. So Taobao has crowdfunding as well. So, similar to those Teespring hats that I was showing, where you can test an idea, see how many people buy it, before you make a production line. This allows for crowd funding of different products. It’s also direct sales, and Taobao really taps into the shanzhai ecosystem because it provides data for the things that you’re selling so that you can respond, just like headlines, to the ones that are trending and quickly spin up new production lines.

Alibaba Express handles shipping logistics. So the difficulty of moving atoms across countries becomes streamlined.

And then there are also Western networks, and this is probably—I’m not sure—probably how the selfie stick, the hoverboard, e‑cigarettes, first started emerging in Western contexts. And through Kickstarter, through Amazon, it allowed for crowdfunding and direct sales online.

And then also through Instagram. Instagram is a key way that a lot of the shanzhai ecosystem is tested in global markets, based on likes and shares. So people can again, just like with digital content, test an idea before committing to the full thing.

Wired Companies

- A burst of digitally driven productivity.

- Greater access to financing and lower risk.

- Growing base of consumers and richer interactions.

- Lower barriers to innovation.

- New competition as the Internet empowers entrepreneurs and small businesses.

McKinsey Quarterly, China’s rising Internet wave: Wired companies [presentation slide]

McKinsey’s done a report on this on wired companies. And so there’s a number of benefits that a company gets when they connect with the Internet. And obviously there’s this kind of boost in productivity. But as we saw with the t‑shirts, as you get an increase in productivity you also get a flowering of creativity. So points four and five are really relevant to this conversation, where you have these lower barriers to innovation. It’s lower barriers to production, to creation. So that once you have an idea online, it’s easy to realize that and actualize that in physical space.

And then also new competition, because it empowers entrepreneurs and small business. We can debate that point, but the point here is that it’s easier for an individual with a random idea to make a product and then test it in the global market.

And selfie sticks again are a good example of that, because selfie sticks are kind of a spectacle. This is a selfie stick with a light. And it’s a spectacle when it’s being used, and people are compelled to take a picture of it. And when they take a picture of it, they post it back online and then people are wondering, “Oh, where did you get that selfie stick?” So just like those digital memes, the selfie stick becomes part of digital meme culture and Internet meme culture. And then those sales on Instagram are circulating on the same networks on which selfie stick memes are circulating.

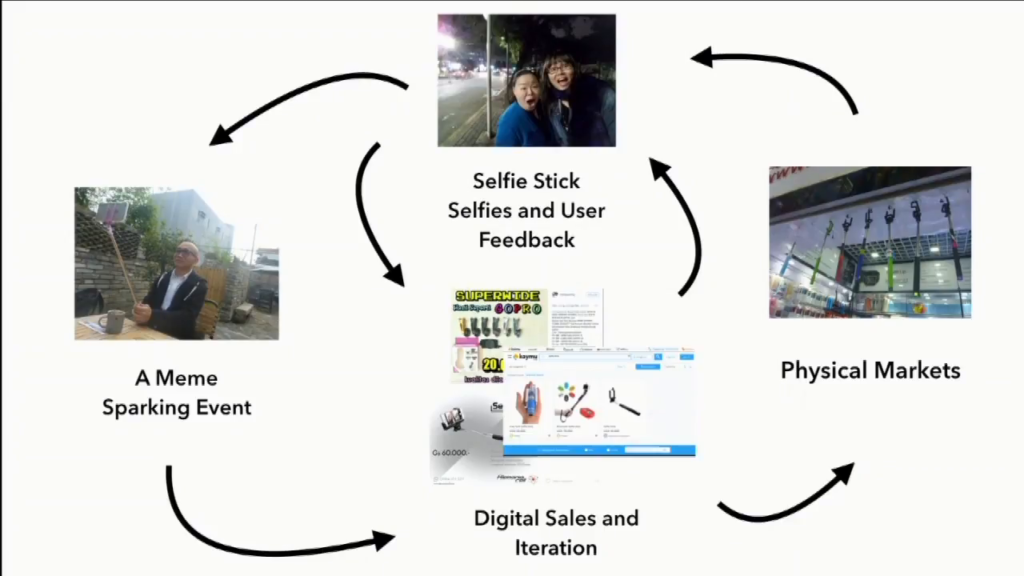

So if we can imagine— This is a very rough diagram; this is much rougher than the other one. But if we can imagine the kind of meme-sparking event— I’m sure we all remember the first time we saw someone using a selfie stick and how odd that looked. And the kind of compulsion to take the picture. That picture as it circulates online, it’s being watched, and people are looking at the trends of selfie sticks. Which ones are circulating, which ones are popular, where are they coming from. And then in the shanzhai ecosystem, people can create a variation, post it online, test that on Instagram, test it on Taobao, test it on other sites. And then get feedback from their users.

And oftentimes they often bypass the physical markets. They just rely on the Internet as a means of distribution. And so the object distribution is looking just as memetic as kind of the way that the digital representation of those objects are spreading. And then finally, if it goes into physical markets it’s often reached a certain scale. And so at that point it becomes like the selfie stick, a global product that you can now find in pretty much every major tourist site around the world.

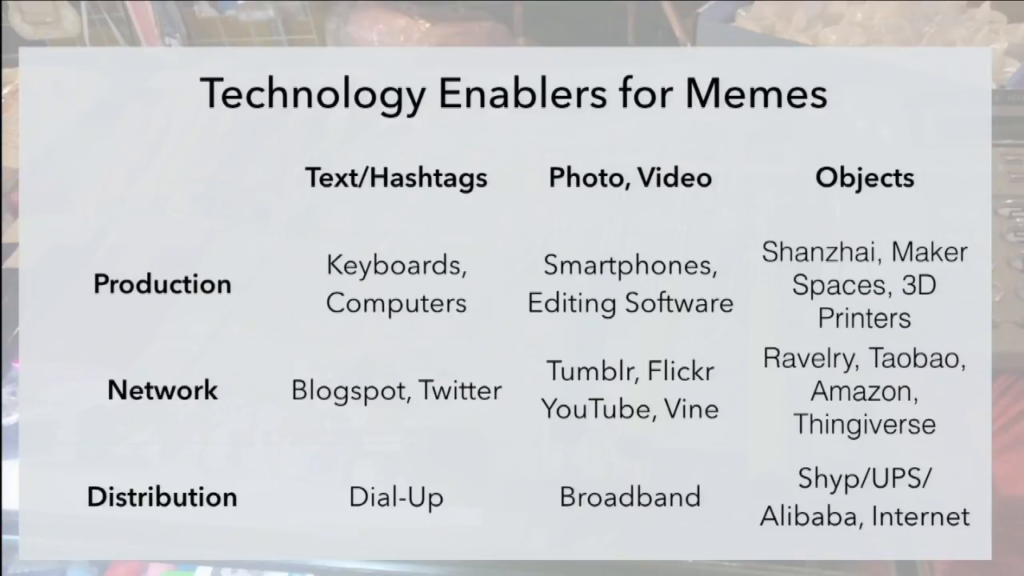

So Internet memes are interesting just as a cultural practice, and then they kind of feed into the kind of human interest in remixing and riffing. And when I think about memes I often think about technological enablers, and looking at memes in a variety of global contexts like China, Uganda, Kenya, United States. And the meme culture often depends on the technological culture and the technological capacity of the context in which memes operate.

And so early hashtag memes often sprung up in the dialup context, or in low-bandwidth contexts. So the technological ability to distribute memes limited people to text and hashtags and ASCII art. And so they used networks like Blogspot or Twitter, and then you have the production capacity for keyboards and computers.

Photos and videos. As broadband comes around in different contexts, that’s when photo and video memes start to emerge. You start to see the remixes of YouTube videos, Vine videos, etc. enabled by broadband and mobile broadband, and then also the emergence of networks that allow people to have that kind of shared space that’s so important to Internet meme culture. And then also the production of this. You need smartphones, you need cameras, you need editing software, to really effectively make a visual meme.

And I argue that we’re at that stage now with objects. And what I mean by that is that we have a means of distribution. We have simple ways to simplify that: UPS, Shyp, Alibaba. And then you have networks that allow for sharing: Ravelry for knitting networks; Taobao for hardware; Amazon for other types of products; Thingiverse for 3D printing. And then you have a means of production as well. You have the shanzhai ecosystem in China, you have maker spaces and knitting spaces in the United States, you have 3D printers as well.

And to some extent, distribution can also happen on the Internet. This is most true with knitting patterns and with scripts for 3D printing, where the raw materials are locally available, but the distribution of the code to make those raw materials into objects can be done through the Internet.

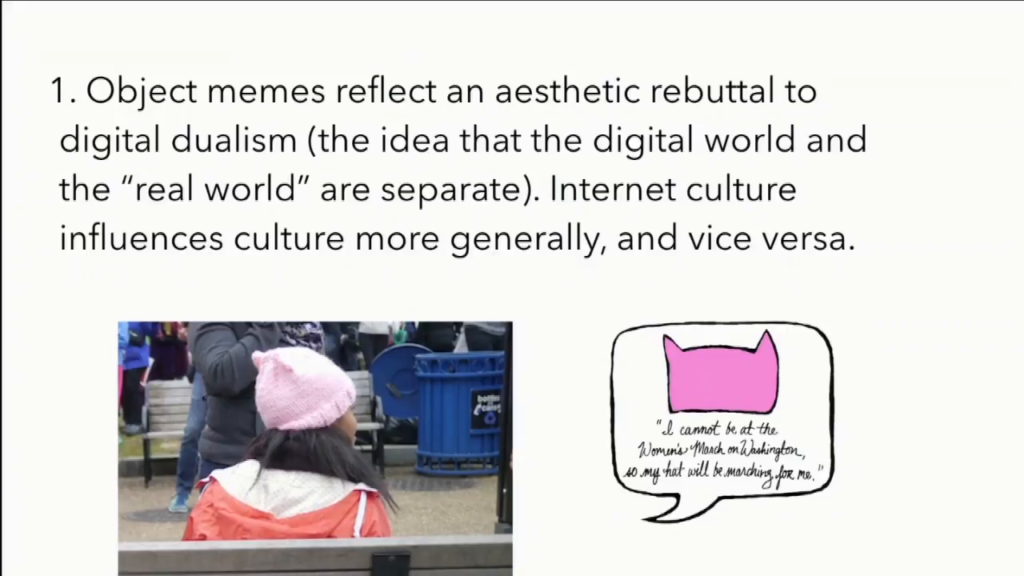

So to conclude, I want to just kind of share three points. One is that object memes reflect an aesthetic rebuttal to this notion of digital dualism. Digital dualism is the idea that the digital world and the real world are separate. We often talk about the real world and the virtual world, but as we see the intersection of Internet memes and object memes, we’re seeing that Internet culture is influencing culture more generally. And vice versa. And so I don’t think it’s useful to think of Internet culture as entirely separate from the culture at large, and we’re starting to see that literally manifesting itself in protest culture in United States.

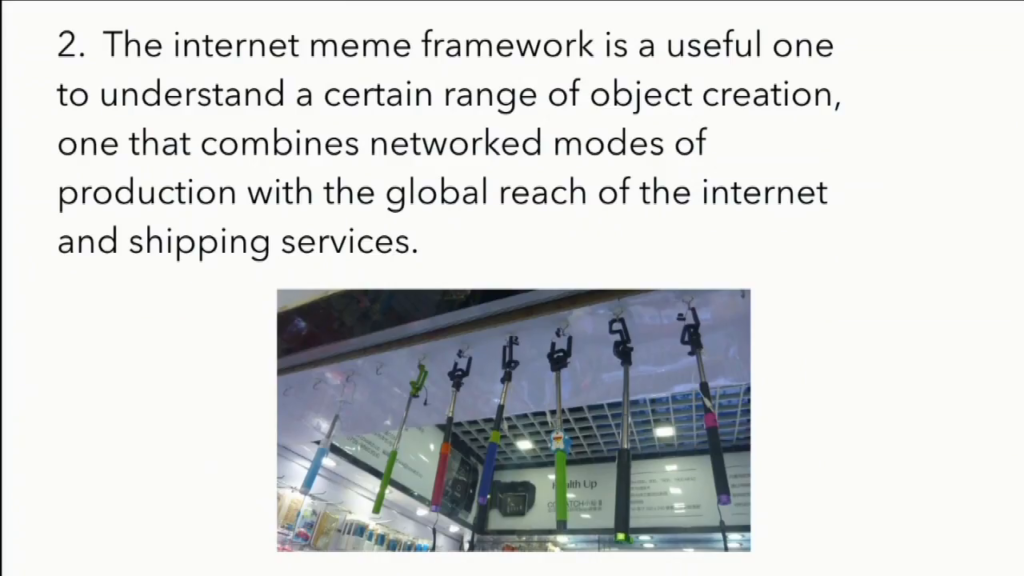

The Internet meme framework is also a useful way to understand a certain range of object production, a certain sort of informal production that combines networked modes of production similar to shanzhai or the hat printing, with the global reach of the Internet and global shipping services as well. The ability to move bits and atoms with just as much ease and efficiency.

And then thirdly, thanks to key technological enabelers like white-label sites that allow for us to interface with the makers and producers, we’re seeing more than gains in efficiency; we’re also seeing a burst in creativity from a multiplicity of people. And so as you get that kind of ease of production you also get an increase in creativity. And so objects produce in this way start to behave like digital objects. They’re remixable, they never quite stay still. They’re informal, they’re produced by individuals, and they’re not produced with kind of top-down supervision. And they appear to be random, much to many people’s consternation but also to many people’s delight. And that randomness is a key part of this. As you look at the objects, a year ago they would have seemed completely random.

So that’s the conversation. Those are the notes I wanted to share. And in true shanzhai fashion, I just wanted to throw those out there and then get feedback and let other people guide the conversation from here. So thank you very much.

Rachel Kalmar: Thank you, An. That was super interesting. I was wondering, are there different characteristics of an online meme that make it more likely to cross over into the physical? You gave a few examples of political meme. Are there things that have to do with identity, or what kinds of demographics would be more likely to engage in this?

An Xiao Mina: Yeah that’s a very interesting question. I do think that—because especially when we’re talking about hats and t‑shirts, those are identity signals. In protest culture before the Internet, we had buttons and pins and stickers and bumper stickers as a means connecting our political identity with kind of a physical object that either we wore on our person or that we drove around with.

And so I do think that at least in the political context, often the digital memes that have to do with a strong sense of self or a strong sense of the emotion tend to do very well. A recent one is “She Persisted,” the meme that popped up in response to the phrase— Something like, “She spoke up. We told her to be quiet. And nevertheless, she persisted,” for Elizabeth Warren. And so things that evoke strong emotion tend to pop up more frequently in these physical objects.

Audience 3: There’s something very attractive about the production model that you showed in China. But I recall hearing about one of its disadvantages about a year ago, which is remember the exploding hoverboards?

Mina: Yes, absolutely.

Audience 3: And it sounds like they came from a system like this, where there were many different manufacturers, they were weakly branded or unbranded, and it was really impossible for anybody whether whether you were an airline, or a store that wanted to sell them, or a consumer, or Consumer Reports magazine—nobody could really tell what were the safe models and which weren’t, because the branding was so weak and the production was so distributed. What are your thoughts on that?

Mina: Sure. Absolutely. I think that’s absolutely right. I think I completely agree. And I think this is why I often reference digital meme culture, because digital meme culture, as we know now, is not always rosy. There’s a lot of fake digital memes floating around. There’s a lot of unregulated memes, so we don’t know what’s real or fake.

Audience 3: [comments inaudible]

Mina: Multiple sources. Yeah, that part I’m less sure of. Definitely hoverboards, because of this weak regulation and because multiple people can produce this, right, and there’s this competition for lower price with maximum sales, right. It’s the same dynamics that we see with digital memes. As we think about content that circulates online, it’s often not necessarily reliable? We don’t know. And we often need an extra layer of verification and checking. And so absolutely, these I informal modes of production with physical objects tend to inherit the same problems digital memes—already we see in the digital context. So I think the hoverboard’s a very good example of that.

Fortunately, selfie sticks don’t explode. This one might, because it does have a battery. And what you do have is e‑cigarettes made in the ecosystem that do explode in your face. And so on the lack of regulation is a risk, just as it is in digital contexts.

Audience 4: I think the problem with the phone was the design of the battery casing somehow had been rounded and it was smaller than spec, so any batter would’ve been bad.

Mina: Okay. Do you know the process by which those batteries are made?

Audience 4: I saw some reports.

Mina You saw tech reports.

Audience 4: It was the case size, the design of the battery itself. [inaudible]

Audience 5: Did you say the 2016 election was the “meme election?”

Mina: A lot of people said that, yes.

Audience 5: Yeah. I’m wondering what the memes were among evangelicals or conservatives, because I think it was used there as well.

Mina: Yeah, absolutely.

Audience 5: What are some examples on that side.

Mina: Absolutely. Deplorables. If you look at the hashtag #deplorables— So, when Hillary Clinton referred to many of Trump’s supporters as a “basket of deplorables,” it was that same practice of reclamation of what was intended as an insult into a form of empowerment. And so you have—

Audience 5: I’m a deplorable. Right.

Mina: Excuse me?

Audience 5: Like, “I’m a deplorable.” Yeah yeah.

Mina: Exactly. And so if you search for t‑shirts, hats, mugs, cloth bags, pillows, you get the same phenomenon. And so you have the deplorables hashtag, the deplorables memes, you had DeploraBall, which was a physical gathering on inauguration day, and then you also have the physical objects. So this kind of meme ecosystem exists just as much time on other right as it does on the left, and with other circles as well.

Audience 5: I wonder if it won the election for him.

Mina: It’s debatable. There’s a conversation around that. Meme practitioners on the right refer often to meme magic that helped elect Trump. And so…yeah. But when we think about memes and influencing elections, I would argue that we really need to think about the larger media ecosystem and how the memes relate to that. And so I think it’s a more complex question simply looking at the memes, if that makes sense.

Audience 6: Thank you for this really thought-provoking talk. I take weird factory process tours. So I’ve got a comment on that last question and another question for you.

Mina: Sure, please.

Audience 6: Swizzle sticks. I’ve actually toured the factory that’s the major swizzle stick manufacturer in the United States. And their secret sauce is they figured out how to combine inkjet printing with injectable plastic mold so that they can do custom swizzle sticks. So that’s another sort of example that you probably wouldn’t come at through these normal means of seeing that.

Another factor I’ve toured—and this was a number of years ago—was a lightbulb factory in Ohio. And like a lot of factories you might tour, the first question you end up asking is “Why are you still here?” You know, why are you still in the United States and not being produced in China? And their answer was “Walmart.” It turns out that Walmart’s product cycle time for light bulbs—like seasonal lightbulbs for Christmas—is too short for the slow boat from China, as it were.

So my question is what’s the shipping network for these products that make them sort of memeable at, you know, Internet speed? Is there something about them that lends them to air shipment, etc. rather than being stuffed on a freighter that’s going to take weeks and weeks, thus completely changing the iteration time.

Mina: Right, right. Yeah, I think with many, because of the particularities of the Pearl River Delta, because it’s been the factor of the world for so long, shipping networks have to go through there. And so what you often see with informal production and kind of informal makers who are not you necessarily part of those shipping networks, they’re able to piggyback on to existing shipping networks to get the products out there. It’s not particularly fast, but it’s much faster than before, because of those efficiencies.

And then what sometimes happens, and this is more on the speculative side, but what I’ve been talking about with people who do the kind of global distribution of some of these informal objects is that one, they’ll test it on Instagram. And then they’ll actually fly someone over, someone who might be flying back to whatever context it is, to then start showing them around and put them in a shop, see if people buy that. And that’s one way that people skim over.

But there is still of course the limitation around the shipping. Something that’s important here is also the logistics of shipping, which is customs, packaging, things like that. And that’s part of what makes things faster, is that you have infrastructure that makes it much simpler to do that. And I think an American analog is a product called Shyp. Are people familiar with Shyp? Shyp allows you to just take a picture of an object and then someone will just show up, pick it up, package it and ship it for you. Very easy, right. So the ability to move the object is still bound by geography and laws of physics. But all the other logistics are streamlined substantially by services.

Rachel Kalmar: I’m going to go off script for a second. I’m just curious, who in this room has engaged in making a physical version of an Internet meme in whatever way you see that? So, I was also curious about demographics of who’s most engaged in this, and also is this mobilizing communities or demographics that wouldn’t ordinarily be engagement Internet memes.

Mina: Yeah, yeah. So, the the demographics that I’m noticing tend to be people in their twenties. So people with a little bit more access, beyond the kind of digital memes. Because these are people who are organizing events. And so Jeronimo Saldaña is a good example of someone who is an organizer and activist who wanted to use hats as a way of galvanizing people to come out.

And I think there’s something important there about the kind of physical manifestation in terms of social movements. Because by putting on these hats, by putting on these shirts, people indicate once they’re in a crowd that they’re part of that crowd. So when you have photographs—and that’s why these pink hats are really important—there’s no ambiguity about who’s there. It’s kind of a direct address to misinformation networks around what crowds are gathering. So often, we see pictures of crowds that are misused. You know, the photos of the LA protests are actually from Venezuela a few years ago. But with the pink hats it was a very clear code that this was happening, particular to this event.

So in terms of demographics, I do notice that it’s more common with activists and the people that activists are trying to organize and rally.

Audience 7: Rachel’s question sparked this question in my mind. Have you looked into culture surrounding turning memes into Halloween costumes, or the cosplay community?

Mina: Yes. Yeah, I haven’t looked formally. But there’s an annual gathering in New York called HallowMEME for Halloween, where people dress up as memes. And so I think looking at creative communities like cosplay, even street art, these kind of creative communities, long before these object cultures that I just referenced, used the Internet as part of their sharing and their kind of inspiration. And so you have networks where people can post their ideas, post their tips, and then other people in other contexts can then do the same.

And so what’s interesting about looking at this in protest culture is seeing how that again establishes a kind of visual and verbal vocabulary that makes a protest in Chicago, in Seattle, in San Francisco, in New York, all kind of feel the same in terms of the media objects. But I think you have the same phenomenon with other creative communities. Knitting, certainly long before the pussyhats, it was very important that it was also a networked community as much as it is physical.

Audience 8: I don’t know how relevant this is to what you’re talking about, but my favorite cap was from Norway. And it was mostly red, and it had a white and blue stripe. But people kept stopping me on the street and wanting to know if I was a Trump supporter. Finally my wife said, “You know, wearing that cap is just not a good idea.”

Mina: Yeah. So, I think that’s an interesting example of how symbologies can be transformed, the kind of hegemonic meaning of the symbol (like a baseball cap and a red baseball cap), that before it might not have meant anything in particular. It might’ve signaled allegiance to a sports team. But that can then have its meaning overtaken by a larger collective of people who agreed to a certain meaning of that symbol.

And I think that’s why it’s so important to also understand the kind of remix cultures that emerge out of that. Because what people are doing is responding to that hegemonic symbolic symbology of the red hat and trying to transform it into another sort of meaning. So you have “Make America Mexico Again” hats, you have Jose Antonio Vargas who’s an immigrant rights activist, created an “Immigrants Make America Great” red hat, and that’s on his Twitter handle. And so the these attempts to reshape the symbology should be seen as activist actions that try to change the meaning of these things. And whether or not that’s successful is a different debate.

Audience 9: From a non-advocacy stance, I kept thinking about films, like blockbuster films, even. Or perhaps larger indie films that could… Like a hybrid. So you have this marketing of products, that go along with Disney or something like that. And I’m wondering if there could be, or if that would work for them, to connect with the bottom-up approach to get their products connected to the film more widespreadly—widespreaded marketed.

Mina: Absolutely. There’s a different talk I could give for marketers that would be basically the same slides but with different talking points. I think when we’re talking about marketing and film distribution, when when people listen in on hashtags or on trending memes about any given movie, they’re also listening for how the audience is responding to that. And I can think of one example that’s not quite a film but is kind of related, Lego.

Lego had for the longest time distributed instructions for how to use Lego. And they noticed that people were sharing tips on how to make other kinds of bigger products, other kind of Lego combinations. And for a while there was a little resistance. But pretty soon they embraced that kind of bottom-up production and then created Lego communities so that people could share that.

So absolutely, I think there’s a lot of value for marketers or people who are trying to promote a brand to think about this beyond the social movement context. And I’m pretty sure I can find an example of a branded selfie stick or a branded hat that kind of dips into this. But no specific examples come to mind right now.

Audience 10: I just want to reintroduce a question that got asked earlier and you put off, which was about the patents and selfie sticks.

Mina: Yeah, yeah. Absolutely. So the his of patents and selfie sticks is actually very interesting. The first patent that I’m aware of was by a Japanese man… I’m going to misquote this, so I’m going to spread misinformation but it’s…I think in the 70s? [speaker’s correction: 80s] who’d created a kind of selfie stick-like device that wasn’t quite ready for the market because you didn’t have smartphones.

And then you see selfie sticks in chindogu, which is a Japanese art of creating useless inventions. And I think that was in the 80s. [speaker’s correction: 90s] And so back then it was deemed as a useless invention but again, because the cameras hadn’t caught up, the networks hadn’t caught up.

And then there is a—I believe he’s Canadian, created another patent for a selfie stick. And thinking about patent law’s a little outside my—

Audience 10: [comments partially inaudible] …if the patents are that old they would all have expired.

Mina: Many of them yeah, I believe so. But also there’s this question—and a patent lawyer would have to comment on this. Given the variation of selfie sticks that you’ve seen, does the patent cover all those variations. Because again, when we look from afar it always looks like there’s one selfie stick. But when you actually go into depth into what’s happening in Shenzhen, there’s actually a wide variety of variation. And the original patents probably look very different from this one with the light, for instance.

Kalmar: I have a follow-on question, which is, in your research or in research of other people, do you know of anybody that’s mapping out the evolution of some of these memes, especially with the physical part. Again I’m curious about the selfie stick. Like, how it spread. Do you know of anybody doing that kind of work?

Mina: No. I’m not, actually. If there’s other people familiar with this I’d be great— I’m actually interested in starting to map one of these. I suspect—I have two hunches right now and I’ll just say them on record—is that the karaoke mic for smartphones, and also certain types of Bluetooth headphones might be the next thing that kind of percolates in global markets. And so I’d be really interested in working with someone to track that.

The logistics of that are very difficult because you need people who can go to factories, visit them, see how those are made and then track that online. And then start tracking the global distribution. Much of the production out of Shenzhen is designed not for US or Western markets but for global markets in Africa, parts of Asia, and Latin America. And so you need a pretty broad research network to really follow that. But I’d be thrilled to work with people on that if there’s any interest.

Audience 11: A [inaudible] question about language. In the 1800s, studies of the demographic transition showed that patterns of changing fertility went by language, very fine language group divisions. And I wondered if anyone’s looked at the role of language, especially in non—in Africa, or in places where there’s a wide variety of languages and pretty low bandwidth.

Mina: Yeah, that’s another core interests of mine, is actually language barriers on the Internet and how how language pairs exacerbate existing inequalities. And so there’s actually a big challenge with shanzhai makers. Most of them only speak Chinese, obviously. And if they do speak English, it’s not necessarily vernacular, fluent English. And so there’s a strong interest from shanzhai communities— They can make things, but it’s very hard for them to kind of market it and get it out there to the broader world. Just in English, English alone. And so a lot of shanzhai makers will just make something but it won’t necessarily see the light of day because you kind of have a gap from production to distribution and marketing.

And so certainly in the contexts we can extrapolate. I don’t have specific examples, but everything I’ve looked at have been typically majority languages of a given country. So it might be English, Spanish, Indonesian. But not the indigenous languages or local languages. On the other hand, because these are physical objects, because digital meme culture is often language-agnostic, these things tend to spread regardless. But yeah, that’s largely speculation. I haven’t dived into that specifically.

Audience 12: During your talk you spoke briefly about how companies use Instagram to market their products. Can you speak a little bit more about that?

Mina: So the way that an Instagram marketing might work is a company—and typically they’re small shops who have a physical stall. So this is an extension of the idea of physical stalls which are common in China, where an individual will have a small shop with their products. But to extend their network, they’ll often use a place like Instagram or WeChat to market (so specific products they have), and then test that with likes and see if people are interested in principle to the idea.

So this becomes a low-cost way to test it, very similar again— I use this analogy of headline testing for online newspapers, because it’s a very similar process to that, where newspapers will test ten different headlines. And they’ll see which one really percolate. And it’s very similar to that with Instagram.

And the Instagram strategy is very common in the Global South. And part of the reason it is that common is because people are already there, on Instagram, on their mobile phones, and it’s much less of a hassle for someone to just scroll through Instagram than it is to go to a dedicated web site that might not be mobile-ready.

Kalmar: Great. Let’s have another round of applause for An. Thank you.

Mina: Thank you.

Further Reference

Pepe, Nasty Women, and the Memeing of American Politics, by An Xiao Mina, at Beacon Broadside