Matthew Kirschenbaum: Good afternoon everyone. Thanks for coming out for another Digital Dialogue. It’s my pleasure to introduce you to Dr. Lori Emerson, assistant professor of English at the University of Colorado, Boulder. Lori is heavily associated, as many of you know, with the emerging media archaeology movement but she was in fact trained in the Poetics program at SUNY Buffalo, and this is not the disconnect it might at first seem.

Working very much in the tradition of figures such as Johanna Drucker and Marjorie Perloff, Lori understands poetry as media and indeed media, through its capacity to offer resistive and frankly difficult experiences, as poetry. All of us who follow her in this work are eagerly awaiting the publication of her first monograph Reading Writing Interfaces, which is coming out in June [2014] from Minnesota. The book, however, is only a partial index of the extent of Lori’s intellectual leadership. Its counterpart exists in her innovative, demanding, and already highly-influential work with the University of Colorado’s Media Archaeology Lab, an entity which she conceived, established, and now directs.

Lori has amassed dozens of vintage computers. Her collection absolutely dwarfs MITH’s outside. They range from a rare and precious Apple I to such mainstays of the personal computer revolution as Commodores, Kaypros, and Macs, and she also collects software, documentation, and ephemera. If you’ve been there to see it, it takes the breath away. And this work has been recognized by entities including both the Library of Congress and the Internet Archive.

Lori thus comes to us at the end of the beginning of a career that has very quickly established her as one of the central figures in the conversation around media materiality, texts, and technologies. In addition to Reading Writing Interfaces, 2014 has also already seen the publication of The Johns Hopkins Guide to Digital Media, which she co-edited, and thus the fliers we’ve circulated.

So today we have the privilege of hearing some of her newest work, and I think I can do no better than the epithet that Bruce Sterling and William Gibson bestowed on Ada Lovelace in their portrayal in The Difference Engine. Please welcome Lori Emerson, The Queen of Engines.

Lori Emerson: Thank you so much everyone for being here. It is a genuine honor for me to be here. I’ve followed MITH from afar and admired it very much for quite a number of years now. So it is great to be here.

What I’d like to do for probably the next 40 to 45 minutes is just first of all talk about how Reading Writing Interfaces as well as the Media Archaeology Lab underlie my next/current project that I’m calling “Other Networks,” which will lead me into an explanation of my kind of mysterious title “There Is No Internet.” And I’ll finish with talking about specific examples of other networks. When I say “other networks” I’m talking primarily about networks that were outside or before what we now call The Internet. So if you don’t mind I’m going to start first by talking about Reading Writing Interfaces and just sort of connecting the dots between that and what I’m doing now.

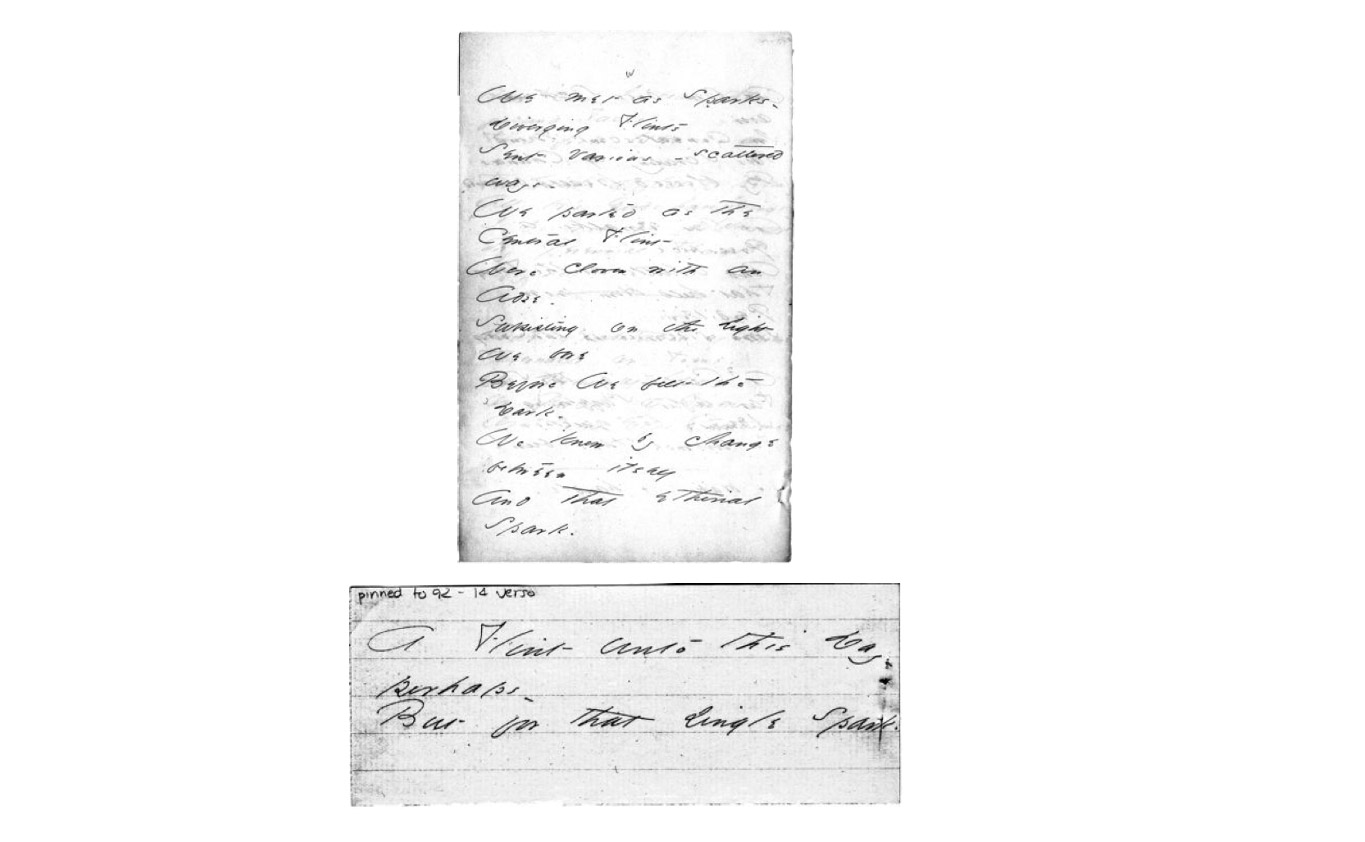

Facsimile reproduction of Emily Dickinson’s pinned poem A91-14a, “We met as Sparks — Diverging Flints”

For the last three years or so I’ve been immersed in working through a Russian doll-like complex of nested ideas that I’m actually still working through. A lot of the basic ideas for my current project actually emerged in an essay I wrote in 2008—which is kind of hard to believe—called My Digital Dickinson. This was my first attempt to read older media and newer media against each other. In this case it was reading Emily Dickinson’s fascicles, or her little hand-made, hand-sewn, hand-written booklets against digital media, drawing on a range of digital poems that I thought were self-conscious about their interface. The point was not to say that if Emily Dickinson could she would’ve produced hypertext poems, and the point was not to say there’s this nice neat linear arc running from her work in the late 19th century to the present, but rather I wanted to sort of refamiliarize contemporary digital interfaces and the way they’re rapidly moving toward reducing readers and writers into consumers whose access to the machine is limited to the surface gloss of a nearly invisible, supposedly intuitive, interface. So I was trying to unsettle this well-trodden linear narrative of technological progress by swinging back and forth between the 19th century and the present moment. I tried to position Dickinson not only as a poet working through the limits and the possibilities of pen, pencil, and paper as interface but also one through which we can read 21st century digital literary texts. This is one example of a digital literary text that I talk about:

My [inaudible] is that this back and forth between past and present had the potential to be disruptive, as I already mentioned. Disrupting this narrative of technological improvement that seems to be driving the disappearance of the digital computer interface under the guise of the user-friendly. So over and over again we’re told that computers are only getting easier, more intuitive, and more natural to use, or at least so the story goes, until you either try to exactly understand how your digital device works or until you try to create outside a corporation’s rigid developer guidelines, or until you come up against the impossibility of working with a closed device whose “seamless,” “natural,” and intuitive user interface doesn’t in any way conform to your own sense of nature or intuition. And it can’t be rebuilt, remade, or reassembled in your own image because in computing, words like “seamless” and “natural” are code for “closed.”

So the essay on Dickinson became the seed for most of the work I’ve done since then. In Reading Writing Interfaces I argue that Dickinson’s fascicles, as much as writers use of mid-20th century typewriters and late 20th and 21st century digital computers, are now slowly but surely revealing themselves as media whose functioning depends on an interface that defines the nature of reading as much as writing.

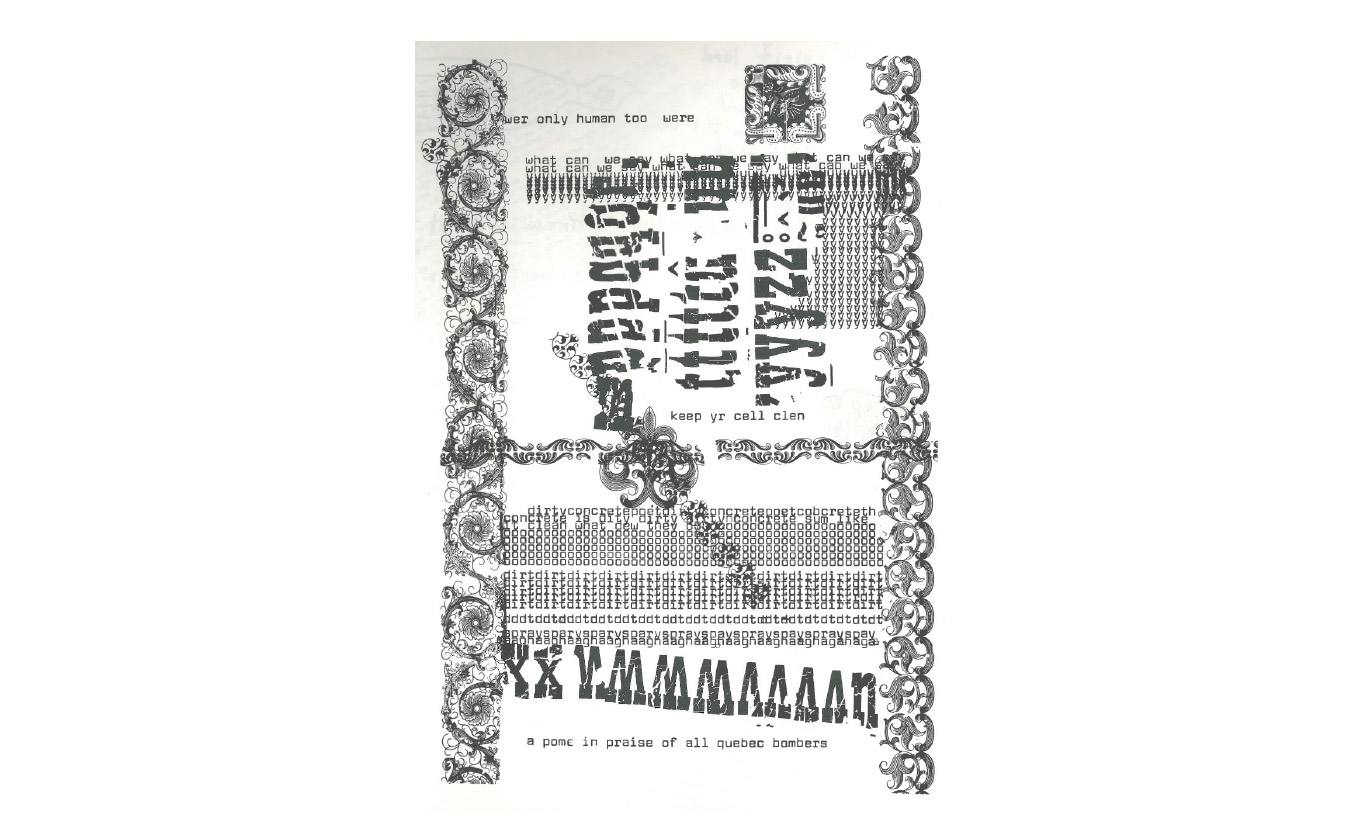

Here’s a dirty concrete typewritten poem from 1973 by a Canadian poet named Bill Bissett.

This is something that I talk about in the third chapter. I talk about typewritten dirty concrete poems as instances of media poetics. These poets are working with and against the affordances of the typewriter, very much the same was as Internet artists might be working against and with the Internet.

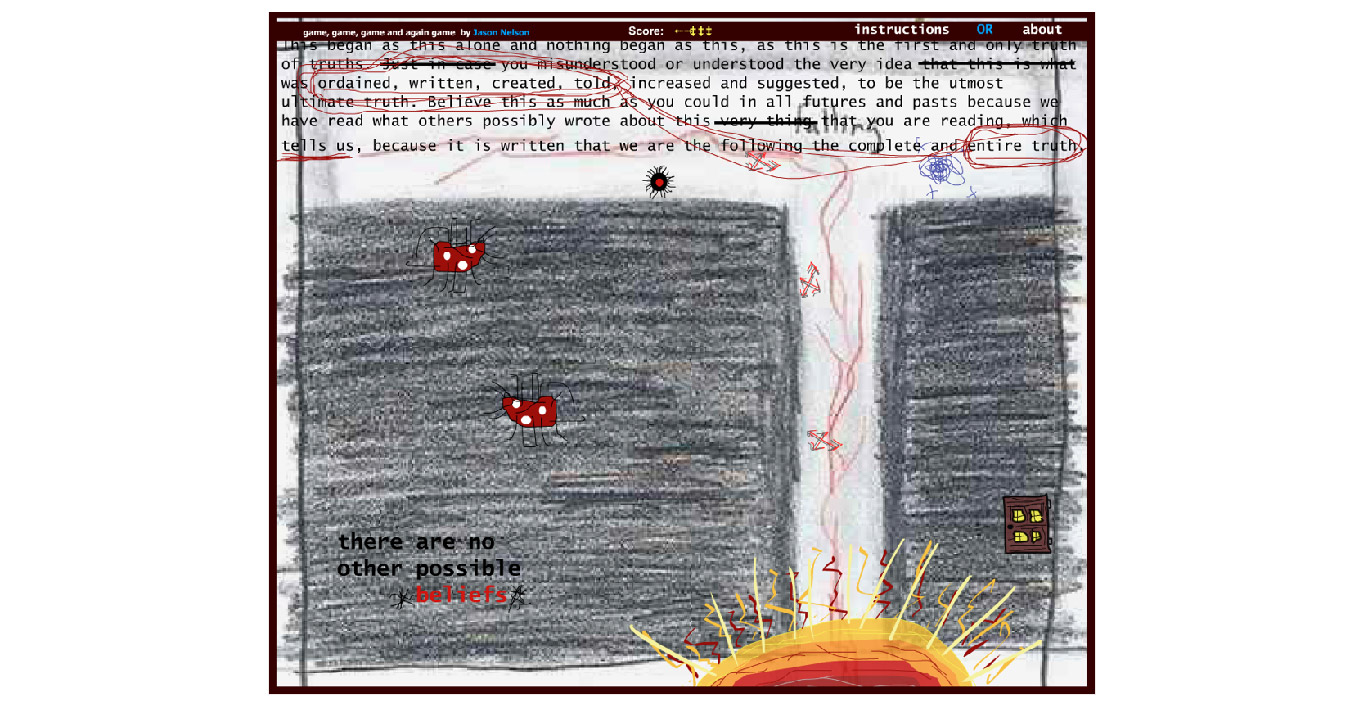

And this is another example, Jason Nelson’s very messy aesthetic where he’s working against the clean aesthetic of the web.

Screenshot from Jason Nelson’s digital game-poem “Game, Game, Game and Again Game” (2007)

So nowadays, interface actually acts as a kind of magician’s cape continually revealing through concealing, and concealing as it reveals, and with the advent of so-called interface-free devices such as Google Glass and the iPad, and when I say “interface-free” I mean it in the sense that they brag that there’s no instruction manual, and in the sense of Apple’s and Google’s favorite marketing slogan of the moment, “It just works.” Largely what’s at issue in Reading Writing Interfaces is revealing what these digital devices are concealing. I show how “invisible” and “user-friendly” are used quite deliberately to distort reality by convincing users that these interfaces are the only viable option for users who aren’t already programmers. Interfaces that depend on and then celebrate the devices entirely closed-off both to the user and to any understanding of it through this glossy interface. So the message is consistently this: Either you let us make it easy for you, or trust us you’ll be swimming in a sea of non-standard competing technologies that depend on your being a “hacker.”

One of the key chapters of my book, which is chapter two, returns to manuals, popular magazines, journal articles, and technical reports by companies like Xerox and Apple, and also advertisements from the early 70s through the mid-80s, to look at other versions of user-friendly that were being proposed in the context of interface design. In other words, what I look at is the philosophies driving debates in the tech industry about the need for user-friendly, standardized interfaces, and the consequences of the move from the command-line interface in the early 80s to the first mainstream windows-based interface introduced by Apple in the mid-80s. My argument for this chapter, which becomes a kind of touchstone for the whole book, is that this move from a philosophy of computing based on belief in the importance of open and extensible hardware (In other words you could lift up the lid of the computer, you can swap boards in and out, you can do all kinds of things.) The movement from that to the broad adoption of the supposedly user-friendly graphical user interface, which is really exemplified by the Apple Macintosh that came out in 1984, that was not exactly hermetically sealed, but users were warned that they might get an electrical shock if they tried to open it up. This was apparently actually a technical glitch, but I think it was a convenient way to really discourage people from opening up their computers. This shift from one to the other fundamentally shaped the computing landscape and inaugurated the era we’re living through right now in which users and writers and artists in particular have little or no access to how our devices actually work.

That book project as well as what I’m working on right now have emerged from thinking through media archaeology as Matt already mentioned, as well as building, curating, and tinkering in the Media Archaeology Lab. Media archaeology has continued to really resonate with me, partly because of the way that certain theorists use it to undertake, as Geert Lovink puts it[PDF], “A hermeneutic reading of the new against the grain of the past, rather than telling histories of technology from past to present.” So on the whole, media archaeology doesn’t try to reveal the present as an inevitable consequence of the past but instead it tries to describe the present as one possibility generated out of a heterogeneous range of possibilities.

The other aspect of media archaeology that I draw from a lot is its interest in keeping alive what Siegried Zielinski calls variantology, or the discovery of individual variations in the use or abuse of media. He is especially interested in variations that defy this move that I’ve already sort of touched on toward standardization and uniformity in our digital computing devices. Following Zielinsky, I continued to be interested in uncovering media phenomena as a way to avoid reinstating this model of media history that supports narratives of progress and that almost totally neglects dead ends in media, neglected media, failed media, dead media of all kinds.

This can take the shape of discovering alternative hardware or software but it can also take the shape of, as I’ll talk about in a minute, looking at telecommunications networks that never came to be. I can see this notion of variantology regularly come to life as donations come into the Media Archaeology Lab. They’re (I find them to be often beautiful and clunky) oddities that come into the Lab, usually by owners who have some sort of prescient sense of the value of their beloved machine that was almost certainly a commercial failure. One of my favorite examples to demonstrate this is this Vectrex Gaming Console. I think it was actually only produced for a year, maybe a year and half, and it uses vector graphics and you can see there on the left that it has a light pen. This is a great example of something from the past that in many ways works better than what we have now. It’s much easier to use. I’ve used this Vectrex to create animations in a couple of minutes. It’s true that it doesn’t have the speed of contemporary devices, but I don’t think speed needs to be the only criteria for better.

With a bit of funding and the help of a small army of volunteers and a couple intrepid grad students, the Lab has really built up its collection in the last couple of years. I think we house up to 1500 individual items right now. That includes games, manuals, printed matter of all kinds, hardware and software. I’m trying to focus the Lab on the history of personal computing so we do have an Altair computer from 1975 or 76, through to the late 90s. But I’ve also had a hard time saying no to other analog oddities that find their way to the lab. The Fisk planetarium on campus donated some magic lanterns and projectors to us. We have a magic lantern from 1907 that still works perfectly fine. So that is one of the many compelling arguments that could be made from the lab, is how…the notion of planned obsolescence, right? We have computers in the lab that are thirty years old that work perfectly and in their own way they do provide elegant solutions to present problems.

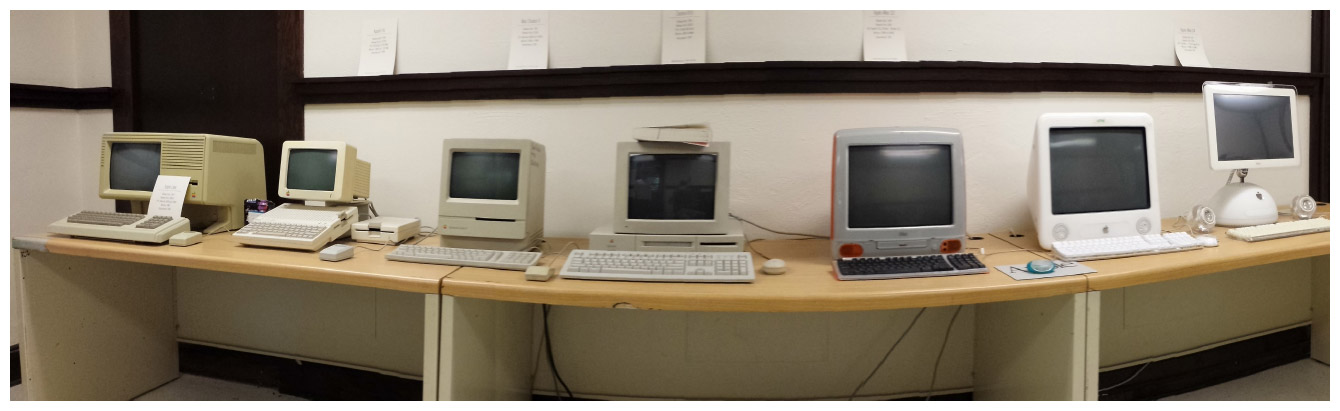

MAL early Apple Computer Collection

This is our early Apple computer collection. The computer on the left, you can see there’s a little something poking up here, that’s the Apple I. It’s not an original Apple I, I’m sorry to say. We have a network administrator on campus who loves the lab and so he built us that Apple I replica.

So far I’ve touched on three lines of thought in Reading Writing Interfaces and now that I’ve arrived at my next project I have the opportunity to work through some of these lines of thought in a different context. As of this past September I’ve been working on a two-part book project that again I’m calling Other Networks. It’s a kind of network archaeology of the history of telecommunications networks that pre-date the Internet or exist outside of the Internet. Networks that were imagined, planned, and created right alongside this tumultous history of the user-friendly interfaces and personal computing.

So first from the standardization and then disappearance of the digital computer interface under the guise of the user-friendly, we get the standardization of network protocols in the 1980s and now the de facto disappearance of the Internet through its ubiquity and its hidden, mysterious underpinnings. From the ideology of the user-friendly, we get the corporate-driven celebration of the so-called freedom we’re granted by ubiquitous computing; wearables like Google Glass, and cloud computing which all just works, we’re told over and over again, so we never have to know how it works, where our data goes, how our online interactions are watched and leveraged. I had the opportunity to use Google Glass for three weeks, and I got a real good taste of how exactly that works as I just accidentally randomly sent things to Twitter and Facebook and all kinds of things. And third, from the use of narratives of progress to promote this ideology of freedom through the user-friendly, we get a misleading, extremely US-centric narrative about how “the” Internet came into being based on an often false binary that’s put forward from the 1960s that pits the square bureaucrats at ARPANET against countercultural non-conformists creating open networks around Berkeley, and that celebrates decentralized control in the Internet by calling it open and free.

MAL Apple Desktop Computer Collection

More Apples. That’s the Apple Lisa on the left, which came out in 1983 for ten thousand dollars. And that was the first “affordable” mainstream graphical user interface. So ten thousand in 1983 dollars is about twenty-one thousand in 2014.

Audience: Where is the cube?

Lori Emerson: The NeXT cube?

Audience: The Mac Cube. We’re seeing up to the lamp-like iMac, but they also made that wonderfully beautiful cube.

Lori: I remember. I just display what people give me. If you have one…

Audience: I actually do.

Lori: Fascinating.

Audience: How big is your carry-on?

Lori: Limitless, for today.

So just to explain my skepticism toward free and open, I recently came across a great example of the way the celebration of and advocacy for freedom online nowadays is used in the service of this late capitalist, decentralized control. And in this case ubiquitous surveillance in a growing number of cities around the world is now actually used to subsidize free wifi, and the latest addition is small city in Israel called Ramat HaSharon in which a free wifi program was created not as a decision by city officials to support or empower its citizens, but actually as a byproduct of its apparently benign-sounding project called Safe City. This was designed to allow city officials to quickly respond to catastrophes and emergencies as well as, as one reporter put it, “ensure civic safety and increase real estate values through a surveillance network of cameras and sophisticated communications.” This of course sounds very similar to NSA officials’ attempts to protect their ability to continue mass surveillance because the logic is that they’re protecting the US from terrorist attacks.

When I was researching Reading Writing Interfaces, I was continually and maybe naïvely floored by how late capitalism makes possible these perfect reversals in the computing industry. But now I see how any dig through pre-internet history inevitably turns up yet more reversals, so that when we look at these free wifi programs what we’re really seeing is the end result of an almost total hollowing-out of free and open as a way to describe early networks, and then their makeovers so that while nowadays free and open Internet can occasionally be used to coordinate mass action, more often than not this free and open Internet is the enabling technology for communicative capitalism.

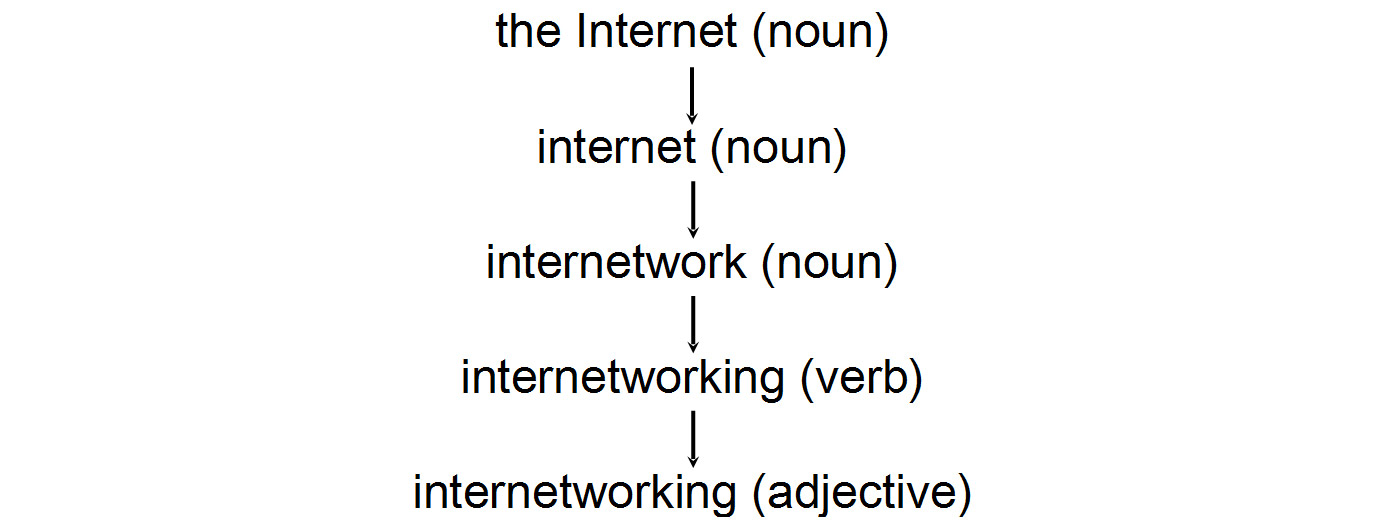

So now finally we arrive at the title of my talk, “There Is No Internet,” because I found that tracing both the turning, twisting etymology of “The Internet” to when it was just referred to as “Internet” and then “Internetwork” while also using writers’ and artists’ experiments on and through networks as case studies, this actually provides a throughline to the messy, contradictory roots of the Internet. The Internet as a singular homogenous entity that people constantly intone came after or out of ARPANET, this Internet actually never really existed. It was instead until fairly recently, and possibly maybe not even now, a lot of different networks with very divergent affordances.

One of the first books I read after I finished writing Reading Writing Interfaces was Howard Rheingold’s The Virtual Community and this was published in 1993 and was where I first noticed his strange use of “Internet.” He kept referring to “Internet” without the “the.” Over the coming months as I worked through manuals on Internet protocols, especially TCP/IP which was created in 1983 as the standard language for networks to communicate to each other, I could see how despite all the shoulder shrugs in the literature about where exactly the term “the Internet” came from, that this term had actually emerged from decades of heterogeneity. So from “the Internet,” introduced to widespread usage as far as I’ve been able to tell in the so-called Bible for TCP/IP called Internetworking with TCP/IP, this was from 1988, to just “Internet” to “Internetwork” with the emphasis on being a go-between between networks, to “Internetworking” as a verb, to “Internetworking” as an adjective to describe the process of transferring packets of information to and from any kind of telecommunication network.

So then the question became this: What were all these different networks that directly or indirectly caused the creation of TCP/IP and later the Internet? What are the affordances of these networks? What sort of communication spaces did they make possible or impossible? In other words, how do these networks work and for whom do they work for? And more difficult to pin down, why do histories of the Internet almost always move directly from the ARPANET of the late 60s to the creation of the personal computer in the late 70s, to the creation and widespread adoption of TCP/IP in the 80s, and then right to Tim Berners-Lee’s invention of the Web in the early 90s, and what’s gained and what’s lost from this astonishingly inaccurate, lop-sided narrative?

Other Networks is going to be comprised of two complimentary parts, or at least so I hope. The first part that I’ve been focusing most on is called Fifty Years of Other Networks 2015–1965 so I’m going to continue with this reverse chronology that I really enjoy. It’s in the lineage of a few critical creative hypermedia studies books that I know of. One is Avital Ronell’s The Telephone Book, and another is, I think it’s just called The Book of Dead Media and it’s very very rare and extremely expensive, not that I’m hoping mine will be expensive. As far as I know there’s only a small handful of these critical creative media studies books.

Fifty Years of Other Networks will be a catalog of networks existing outside of or predating the Internet, and I’m imagining that it’s a stack of unbound loose sheets of paper packaged in a box. Each sheet beginning with the present and moving back into the past will provide metadata of a sort, a description, and a short analysis of an “other network” so that the material form of the project allows readers to actually actively dig through this network archaeology.

The analytical aspect of the project will be driven by a three-fold approach in that I look at the material and technological affordances of each network; the way they were conceived, marketed, and sold; and I think a crucial component of this has to be the way artists and writers in particular were working with and against the foregoing, because I just think that the way artists and writers use these other networks really provides a great test case for how they were pushing up against the limits of what was possible.

What I’d like to do next is just give you five short descriptions of different networks that are going to be in this collection.

Since the project moves from present to past, one of the first networks to appear in the catalog is called occupy.here, and this was created in 2012 in parallel with the Occupy movement. Occupy.here claims that it exists entirely outside of the Internet. I think what they do is they use the Internet as a portal to go off of the Internet, and so it describes itself as inherently resistant to surveillance. It consists of a wifi router near Zucotti Park in New York City and anyone with a smartphone or a laptop within range of it can access it through a portal website that then opens up onto what its creators calls a kind of bulletin board system on which users can share messages and files. Occupy.here is an example of what’s called a “darknet,” a network that uses non-standard protocols, anonymizes its users, and it creates connections only between trusted users. Not surprisingly, darknets have been viewed with great suspicion since the 1970s, when the US Military’s Advanced Research Projects Agency coined the term “darknet” to refer to networks that were unavailable over ARPANET. And then there was a fresh wave of concern about darknets in 2002 that maybe not so surprisingly came out of a group of Microsoft researchers. They published a paper called “The Darknet and the Future of Content Distribution” arguing that the darknet was the greatest stumbling block to their ability to control the use of digital content and devices after they’d been sold to consumers.

As readers dig through these layers of networks in the catalog, I think that they’ll probably start to notice the way the reverse chronology actually turns out distinctly non-linear and maybe more a recursive history of networks, where networks emerge, disappear, and reappear slightly calibrated. I just mentioned that Occupy.here is a kind of bulletin board system, but a BBS is a network that emerged in the late 70s, and nearly all histories of the Internet agree that BBSs died out with the introduction of the World Wide Web in the early 1990s. But there were thousands, I think, thousands of BBSs that existed and so I’m going to have to talk about them. Incredibly, despite the fact that there were thousands of them and they were profoundly influential, there’s only been a lot of self-published first-person accounts of BBSs and there’s a lot of enthusiasts online who like to reminisce about their years running or participating in BBSs, but so far there’s been no media studies book written on BBSs, which is probably the most important telecommunications network of the 80s and 90s. Since the Lab is fortunate enough to have that network administrator that I mentioned to you, we actually now have a telephone line installed in the lab and we’re in the process of setting up our own BBS so that people can call in if they want. I really think that nothing else is going to help me explore the difficulties, and hopefully some joys, of running a BBS than actually trying to do it myself.

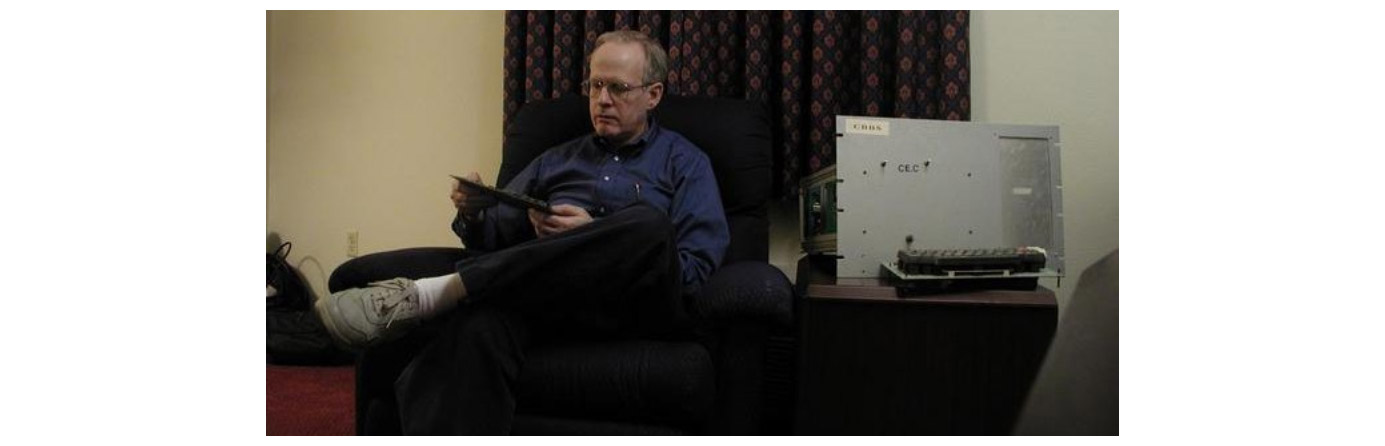

Computerized Bulletin Board System (1978)

The first BBS system was called the Computerized Bulletin Board System that came online in 1978. This is the best picture I could find of it. It’s just the co-founder sitting beside his CBBS. It was originally conceived as a computerized version of an analog bulletin board for exchanging information. Each BBS had a dedicated phone number, which generally meant that only one person could dial in at a time. Also, most BBSs were communities of local users because of how prohibitively expensive it was to make long-distance phone calls, and so these local users could use the BBS to create communities that actually began on the BBS and then extended outwards geographically. They shared files, read news, exchanged messages, played games, and even created art.

ANSI art, for example, was a popular art form on BBSs. It’s similar to ASCII art, which is what you’re looking at right here. I see it as a kind of computer-based visual poetry or form of writing that can only use the 95 printable characters defined by ASCII. ANSI art, however, is constructed from a larger set of 256 letters, numbers, and symbols. I know there’s better examples of ANSI art than the one I’m showing here.

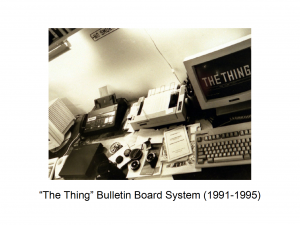

- “The Thing” Bulletin Board System (1991−1995)

- Flier for “The Thing” BBS

One BBS that I’m particularly interested in is called The Thing, and it’s a BBS that New York artist Wolfgang Staehle started in 1991, and it was actually just one month after Tim Berners-Lee launched the World Wide Web. It was used as a kind of online community center for artists and writers, a virtual exhibition space, and later a node in a network of international The Thing BBSs. But what really interests me about The Thing is the way in which the network itself was conceived of as an artwork, rather than any individual pieces of content that were uploaded to it. I also want to mention that the MAL is fortunate now to house a good portion of The Thing hardware, which Staehle donated to us a month ago. Unfortunately he doesn’t remember the username and the password, and we haven’t been able to break in, but hopefully we’ll get around to that soon.

While we’ve not been successful in breaking into any of the machines, I do think that the material traces of one of the most important digital art networks are still meaningful, from the filth of the keyboard on the SGI Indi from heavy use by its system administrators, to the BBS numbers affixed to the front of the machine, to the oddity of The Thing’s eSoft IPAD machine, which bears no resemblance to the Apple iPad, but instead stands for “Internet Protocol ADaptor.”

Here’s some odd facts about the eSoft IPAD. eSoft, I was stunned to find out, is actually a Colorado-based company and it existed just down the road from me in Boulder until December [2014] and I unfortunately didn’t find this out until January. One of their accomplishments was the creation of the IPAD, which is a wonderful kind of liminal technological object, in that it tried to straddle pre-Internet networks and the Internet itself. So eSoft started out making a BBS system called the TBBS, for the Radio Shack TRS-80 computer and later for IBM PCs, and in fact before the Internet Microsoft used TBBS to provide technical support to their customers. In 1993 eSoft created this IPAD as a means to provide access to the TBBS using Internet protocols. So the IPAD soon turned into what eSoft called an “Internet in a box appliance” that gave companies a way to have a presence on the Internet with just one piece of equipment. That was their selling point.

Since my work has always been North American-based rather than just American or Canadian, it’s been a thrill to discover not only that a majority of pre-Internet writer and artists networks were Canadian but also that these networks were some of the most vibrant and influential. I believe that one of the reasons for this inordinate number of Canadian networks is that in 1983 Tom Sherman, who at that time was a video officer for the Canada Council for the Arts, founded the Media Arts section and then launched what he called the Integrated Media Program, which was Canada’s first funding program for digital media arts. I think that really put Canada almost at the top of funding and creation for artists and users of networks. The program explicitly supported work that used new or unusual combinations of media and which had failed in the past to find support. As Sherman put it in an interview a few months after the launch of the program, sounding very much to me like he was under the spell of Marshall McLuhan, “It is always important for public money to be used in a way which either opposes or misuses utilities to a certain degree…” It sort of makes me laugh, it’s so un-American, isn’t it? “…just to show that there is some potential use for different types of use for those systems.”

One of those systems supported by the Canada Council was ARTEX, originally called Artbox. This was founded in 1980 by Robert Adrian and Gottfried Bach in Vienna, and Bill Bartlett in Victoria and it lasted until 1991, which is quite a long time. ARTEX, which stood for the Electronic Art Exchange Program was a simple and cheap electronic mail program designed to be used by artists and writers interested in what they called “alternative uses of advanced technology.” The program and the network were provided by a company named I.P.Sharp Associates timesharing network, which was based first in Toronto and then in Victoria, and which may not so surprisingly had some ties to the Canadian Navy. One example of a writerly use of the network is Norman White’s piece called “Hearsay” from November 1985, which was a tribute to Canadian poet Robert Zend, who had died a few months earlier. Robert Zend was known for being incredibly prolific but also creating really beautiful works of typewriter art or typestracts or whatever term you want to use. One of his most famous works is called “ARBORMUNDI.” “Hearsay” builds on this text that Robert Zend wrote in 1975:

THE MESSENGER ARRIVED OUT OF BREATH. THE DANCERS STOPPED THEIR PIROUETTES, THE TORCHES LIGHTING UP THE PALACE WALLS FLICKERED FOR A MOMENT, THE HUBBUB AT THE BANQUET TABLE DIED DOWN, A ROASTED PIG’S KNUCKLE FROZE IN MID-AIR IN A NOBLEMAN’S FINGERS, A GENERAL BEHIND THE PILLAR STOPPED FINGERING THE BOSOM OF THE MAID OF HONOUR. “WELL, WHAT IS IT, MAN?” ASKED THE KING, RISING REGALLY FROM HIS CHAIR. “WHERE DID YOU COME FROM? WHO SENT YOU? WHAT IS THE NEWS?” THEN AFTER A MOMENT, “ARE YOU WAITING FOR A REPLY? SPEAK UP MAN!” STILL SHORT OF BREATH, THE MESSENGER PULLED HIMSELF TOGETHER. HE LOOKED THE KING IN THE EYE AND GASPED: “YOUR MAJESTY, I AM NOT WAITING FOR A REPLY BECAUSE THERE IS NO MESSAGE BECAUSE NO ONE SENT ME. I JUST LIKE RUNNING.”

Robert Zend, “THE MESSAGE (FOR MARSHALL MCLUHAN)”

Norman White’s “Hearsay” on the other hand was an event based on the children’s game of Telephone where a message is whispered from one person to another and arrives back at its origin, usually hilariously garbled. Zend’s text was sent around the world in twenty-four hours, roughly following the sun via the IP.Sharp Associates global computer network and each of the eight participating centers was charged with translating the message into a different language before sending it on. This is the final version that arrived in Toronto.

THE DANCERS HAVE BEEN ORDERED TO DANCE, AND BURNING TORCHES WERE PLACED ON THE WALLS.

THE NOISY PARTY BECAME QUIET.

A ROASTING PIG TURNED OVER ON AN OPEN FLAME.

THE KING SAT CALMLY ON HIS FESTIVE CHAIR, HIS HAND ON A WOMAN’S BREAST.

IT APPEARED THAT HE WAS SITTING THROUGH A MARRIAGE CEREMONY.

THE KING ROSE FROM HIS SEAT AND ASKED THE MESSENGER WHAT IS TAKING PLACE AND WHY IS HE THERE? AND HE WANTED AN ANSWER.

THE MESSENGER, STILL PANTING, LOOKED AT THE KING AND REPLIED:

YOUR MAJESTY, THERE IS NO NEED FOR AN ANSWER. AFTER ALL,

NOTHING HAS HAPPENED. NO ONE SENT ME. I RISE ABOVE EVERYTHING.

Norman White, “Hearsay” (1985)

I think it’s a great example of media and semantic noise.

I found that the closer to the 1960s I get in Other Networks, the stranger things get, and I could happily talk about this next network called Community Memory for a very long time, but here’s a short summary.

Research One Incorporated was a non-profit corporation founded by four computer science students from Berkeley and they were responding to the 1970 invasion of Cambodia and the resulting shutdown of a number of universities. So their response was to drop out of Berkeley and work instead on setting up computer access for members of the counter-culture. Pam Hart was Resource One President, and she managed to persuade no less than the President of the Bank of America to donate a giant timesharing computer along with money to purchase a 50 megabyte hard drive as a way for the Bank of America to tap into the counter-culture and kind of conveniently align themselves with it. With the addition of a handful of teletype terminals, this timesharing machine turned into Community Memory, which is a prototype of a bulletin board system before such a thing existed, and it lasted from about early 1973 until late 1975. I’ve heard that there were a couple other Community Memory nodes that popped up right after, maybe ’76 or ’77, one of which was in Vancouver, probably funded by the government. Terminals were set up by Leopold’s Records in Berkeley right next to a conventional bulletin board, the Whole Earth Access store also in Berkeley, and at the Mission Street Library in San Francisco.

Community Memory is one of those projects that’s hardly ever mentioned in any pre-Internet history, and if it is mentioned the details on the why and the how are frequently missing or even inaccurate. Maybe a couple of months ago, as one example, commentator Evgeny Morozov published an article titled “Hackers, Makers, and the Next Industrial Revolution” in The New Yorker harshly criticizing (as he’s made his career doing) the way so many people unthinkingly accept the way startup companies and corporations align making and hacking with revolution and freedom. He traces part of this maker culture to the Homebrew Computer Club, which was a computer hobbyist group in Silicon Valley that Woz was part of, and also he traces it to Community Memory. Morozov attributes the creation of Community Memory to Austrian philosopher Ivan Illich’s Tools for Conviviality, and in this book Illich writes, “Convivial tools rules out certain levels of power, compulsion and programming, which are precisely those features that now tend to make all governments look more or less alike.”

While this quote does describe the why of Community Memory, in fact that book came out a year after Community Memory was conceived—and this is one of the great things about this project is that a lot of the people who originally founded these networks are still around and available, and I discovered that one of the founders of Community Memory is living in Halifax and is on Twitter and has a very low profile and is very happy to talk about Community Memory. So one of these co-founders, his name is Mark Szpakowski informed me that the original inspiration for Community Memory was actually Project Cybersyn.

Project Cybersyn dates from the early 1970s in Chile, which under Socialist President Salvador Allende, created a network of 500 telex machines for factory workers across the country to support the newly-inaugurated democratic system and to support the autonomy of workers. The system was most famously used to coordinate a strike of 50,000 truck drivers in 1972 and I think it’s another really great example of how inaccurate and US-centric pre-Internet histories tend to be, and maybe not so surprising in this case considering its Socialist roots. Project Cybersyn also clearly demonstrates how facile it is to claim that a government-supported network must necessarily mean the creation of a closed and bureaucratic hierarchy and the rejection of a free and open network. Free and open in early 1970s Chile actually meant that those participating in building the system wanted to see it used to encourage worker participation in factory management. Like ARPANET, however, Project Cybersyn is often read as a tool not for a more even distribution of power, but actually as a mechanism for centralized control.

Finally I’d just like to briefly outline the second part of the Other Networks project, which will just be called Other Networks and will be the academic monograph part of the project. In my imaginary scenario, both parts of this project will come out roughly at the same time. I don’t know how that’s actually going to happen, but that’s what I’d like. I’ll draw on the catalog to argue more explicitly some of the points that I’ve already touched on today. Moving from the present back through the 1960s and undertaking a kind of network archaeology of the many different and even conflicting networks that existed before the Internet consolidated all the different networks under one protocol, TCP/IP, one finds that the history of how we arrived at the Internet, how it came to be, is much more muddied, contradictory, and stranger than has ever been accounted for. And as I’ve tried to emphasize today, nearly all histories of the Internet are not only misleading and US-centric, but they also tend to create a false binary between the squares from the government, military and large corporations on one side with the desires for networks that embody centralized, hierarchical power structures, and then on the other side the hip homebrew hobbyists and counter-culturalists with their desires for networks that embody free, open, communitarian, and distributed power structures.

While Thomas Frank has already brilliantly shown in The Conquest of Cool how American business, starting from the mid-1950s, tried to align itself with the ideals of non-conformity, hip, creativity, and decentralization, so that again this binary between hip and square actually never really existed, for some reason no one has applied this piece to networking history.

There’s been a few writers like Roy Rosenzweig who have shown bits and pieces from the other side of things. He has pointed out how ARPANET was ironically one of the first to embrace the open technical standards embodied in TCP/IP, and so the ARPANET actually inadvertently sparked the creation of the network that connected previously-disparate networks, now known as the Internet. However after looking at some of the original documents written by J.C.R. Licklider, who’s a computer scientist who ran ARPA in the early 60s and who first came up with the idea of a computer network like ARPANET that he and his colleagues called an “intergalactic computer network” I’ve discovered that the blueprint for a network that’s free, open, distributed, and communitarian is actually all there. So for example, Licklider has written a piece called “The Computer as a Communication Device” [PDF] from 1968, and one of the most frequently-used words in this piece by this bureaucrat and supposedly square, are “community” number one, “cooperative,” and “creative.”

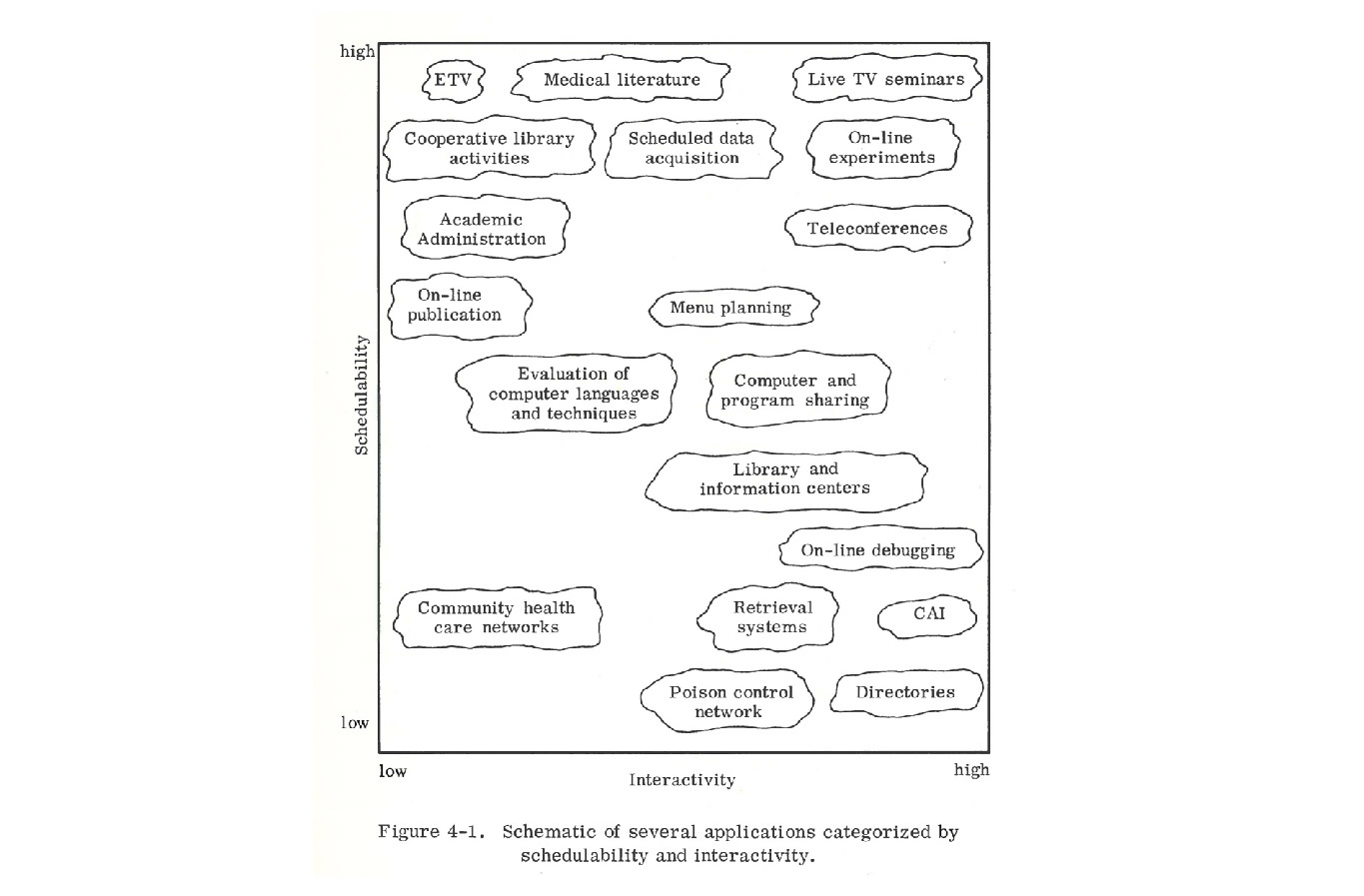

And in the same year (this is another fascinating tidbit) Licklider was playing a central role in trying to create an educational network that he called EDUNET. It’s a network which has almost entirely disappeared from our cultural memory. I just happened to discover it because I have a colleague who was in humanities computing from the late 60s and 70s who donated his books to the Lab, and one of these books is a report on a big EDUNET meeting that took place in Boulder, Colorado in 1967. A fascinating little fact about EDUNET is that Licklider’s plan for this network also contained the seeds for some version of MOOCS, which in ’67 Licklider believed would “increase teaching efficiency,” in his words, allowing teachers to teach more students with what he called “programmed packages of remedial units.”

So this then returns me to my earlier articulation of what I’m trying to argue. By drawing on a catalog of fifty years of other networks, also moving from present through the 1960s through these technical and user-based accounts of other networks, asking both how does it work and whom does it work for, Other Networks will explore the strange mix of both liberationism and libertarianism that’s at the roots of our present-day Internet, an Internet that just in the last couple of months many have declared as dead as the Libertarian dream of a totally unregulated free market online can now be realized as corporations like Verizon have been given permission to determine our access to information.

But my sense is that if the Internet is dead, if it’s no longer the free and open web we thought it was, that it’s actually not newly dead. Its roots in the 1960s actually contained the seeds of its own demise.

Thank you so much for your attention.

Further Reference

“From typewriters to telematics, media noise in Robert Zend” at Lori’s blog, on Norman White’s “Hearsay” and Robert Zend’s “ARBORMUNDI.”