Jay Springett: So I work professionally in and around the blockchain space. I have been involved in the solarpunk movement since 2013. I’m the editor of solarpunks.net. And I’m also responsible for coining the term stacktivism many years ago, for my sins. So, I will begin.

So I’m @thejaymo on Twitter, and you can find me professionally theruderal.com. This talk is in four sections. I’m gonna be talking about the present, going to be talking about visions of the future, narrative strategies, and strategic narratives. And I’d like to say thank you to all of the speakers that you’ve heard so far tonight. And I’m hoping my talk might be able to hit everything that everyone’s spoken about. With luck.

So, in part one, In Context. Terra0 are utilizing blockchain technologies to build automated systems to allow a forest to own and utilize itself. In New Zealand, rivers are finally becoming people. Mountains too have been granted legal personality.

Corporations are already people, my friend. States are running initial coin offerings. And China needs more water, so it’s building a rainmaking network three times the size of Spain.

More than 500 burners have been deployed on alpine slopes in Tibet; the age of climate megaengineering is already upon us. And most atolls will be uninhabitable by the mid 21st century.

So we are starved for visions of the future that will sustain us. The science fiction author Cory Doctorow said, Science fiction isn’t predictive of the future. It tends to be about diagnosing our current aspirations and anxieties.

So then, this is a picture of Netflix’s Altered Carbon. Cyberpunk is about the politics of the 1980s. It is about urban decay, and corporate power, and globalization. Cyberpunk explores the way that technology shoves human life into ever greater levels of extraction like cyberspace

, the rise of zero-tolerance policing, anxieties around healthcare and the psychological toll of the cold forever war, and the possibility of nuclear annihilation. By the way, the Robocop headquarters is like, a vastly underappreciated by cyberpunk icon, in my opinion.

Many of the concerns of the cyberpunk genre have come true. The rise of corporate power, ubiquitous computation, and the like. Robot limbs and cool VR goggles. But in many ways, it’s far far worse. The existential threat of climatic change leans over all of our futures, and our institutions seem to be unable or unwilling to do anything. But in the dark future that cyberpunk produced, the 80s as a decade were bookended by the eradication of smallpox in 1980 and the global ban of CFCs in 1989.

Our current popular culture sees no such hope. It is full of narratives of individual superheroes, or saviors, in increasingly desperate attempts to band together to defeat existential crisis of ever-increasing magnitude. The science fiction author and futurist Madeline Ashby on her blog gave us one piece of advice at the end of last year. And that is to talk loudly, and frequently, and in detail about the future that you want. Because you can’t manifest what you don’t share.

So, then. I am a solarpunk because the only other options are denial or despair.

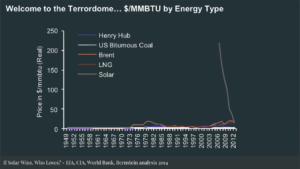

Solarpunk as Narrative Strategy. In 2014, the EIA, CIA, and World Bank published a graph charting the falling cost of solar and titled it “Welcome to the Terrordome.” But we don’t see terror in this future. Solarpunk envisions a world with a drastic technological shift towards renewables, and decentralization empowers movements for social justice and economic liberation. It sees infrastructure as a site of potential resistance.

Solarpunk is a movement in speculative fiction, art, fashion, and activism that seeks to answer and embody the question, what does a sustainable civilization look like, and how can we get there? It is concerned with the struggles en route to a better world, and solutions to live comfortably without fossil fuels, to equitably manage scarcity and share abundance, to be kinder to each other and to the planet that we share.

Whilst the term has some antecedents online, solarpunk truly began in Brazil in 2012, with the publication of an anthology subtitled “ecological and fantastic stories in a sustainable world.” And today, the English translation has just gone up for preorder on Amazon, if you wanna go check it out. Since then in 2012, the idea has been picked up as a flag, or as a banner, by a diverse community of activists, writers, artists, and technologists. There are now multiple anthologies of short and not-so-short fiction you can find online.

Rejecting both the low-life and high-tech dystopias of cyberpunk and the low-life and low-tech survival slogs of post-capitalist science fiction like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road or Mad Max, solarpunk aims to cancel the apocalypse. It attempts to foster a sociocultural environment which emphasizes individual autonomy, consent, unity and diversity, with free egalitarian distribution of power. Of course, with these principles comes polyphony. One cannot speak for other solarpunks, only be in dialogue and occasional chorus with them.

Diane Cardwell, Solar Power Battle Puts Hawaii at Forefront of Worldwide Changes

The upcoming 21st century shift towards clean energy opens the future to an age of innovative dissent. Solarpunk seeks to leverage the narrative logic of a decentralized infrastructure and its technologies to change the kind of politics and futures that we can imagine. A solarpunk plot unfolding in real time right now is Spain’s attempt to make it illegal to use solar panels to go off the grid, which has since developed into the sun tax on photovoltaic installations. Power has already seen the possible points of narrative entry and is already circling wagons around the kind of future that we want.

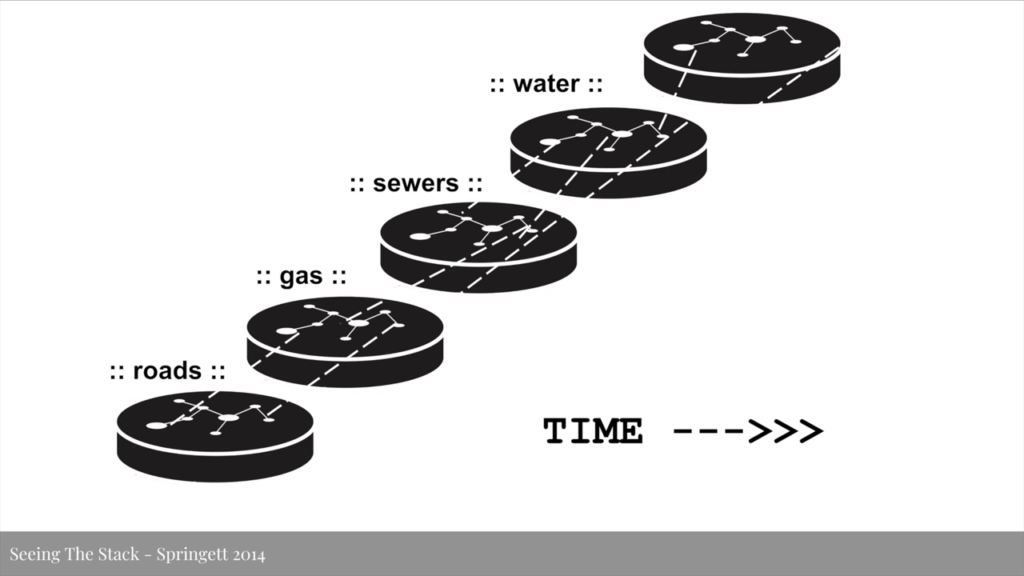

Solarpunk is not unaware of science and technology studies and infrastructure theory, and that has quite rightly found that certain technologies internalize certain ideologies. The effects of these internalized ideologies are all around us, in some sense. The vertically-integrated but interdependent stack of technologies that keep us alive has grown over time, but the historical and the internal biases of the people that made them, and the technologies themselves, somehow lean through time and still touch us today.

Olivia Rosane, Anthem of the Sun: Solarpunk aims to cancel the apocalypse

Solarpunk is also not unaware of the fact that new technologies don’t inherently alter the power dynamics that govern the division of domestic labor, or even call them into question. Solarpunk attempts to play with the power dynamics by imagining new ways of being in the world, with the new technologies as props.

Solarpunk creates a multitude of spaces for indigenous sovereignties, reproductive justice, and radical queer politics. It contrasts the grim futures of cyberpunk with a bright viridian green optimism. Solarpunk is a response to Szeman and Boyer’s call that we need to map out other ways of being, behaving, and belonging in relation to energy in order to reimagine modernity in the face of global warming. Rhys Williams on solarpunk in the LARB wrote,

It’s possible that a shift to renewables will spell the end of capitalism; that alternative forms of energy are not compatible with capital’s grail of profit and growth. [But] where there’s a capitalist will there’s usually a capitalist way. The necessity of energy transition provides us with a historical moment of crisis in which opposing ideologies are wrestling over the future not only of energy, but of society. The point is less whether renewable energy automatically equals a fairer society, and more that the massive infrastructural changes ahead provide leverage to institute something better.

Rhys Williams, Solarpunk: Against a Shitty Future

In solarpunk, energy is explicitly political, and the unfolding processes that renewables provide—the transmutation of wind, water, and solar—projected forward result in new human lifeways. It is a humanity in communion with the environment.

Its “futurism is not nihilistic like cyberpunk, and not quasi-reactionary like steampunk. It is a great tragedy that steampunk as a genre was not decolonial to its core from its inception. Optimism and pessimism, utopia and dystopia are not really mutually exclusive. They are coexisting concepts, like two sides of the same coin. And a coin is always possible to flip. Progress/development is not the same as growth, and an integral thesis of solarpunk should be about decoupling the first from the second. More is not better.” Solarpunk is punk because optimism and the practical route forward are very much not in vogue culturally, or are they the status quo.

Elvia Wilk, Is Ornamenting Solar Panels a Crime?

Solarpunk treats sustainable innovations as a problem of politics as much as engineering. It is not a genre that relies on huge technological leaps into the future, nor by taking wistful glances at the past, but by looking laterally at what’s already in the world and projecting it forward. And the world right now around us provides a rich soil of ideas and action from which our struggles to an on-route to a better world can grow.

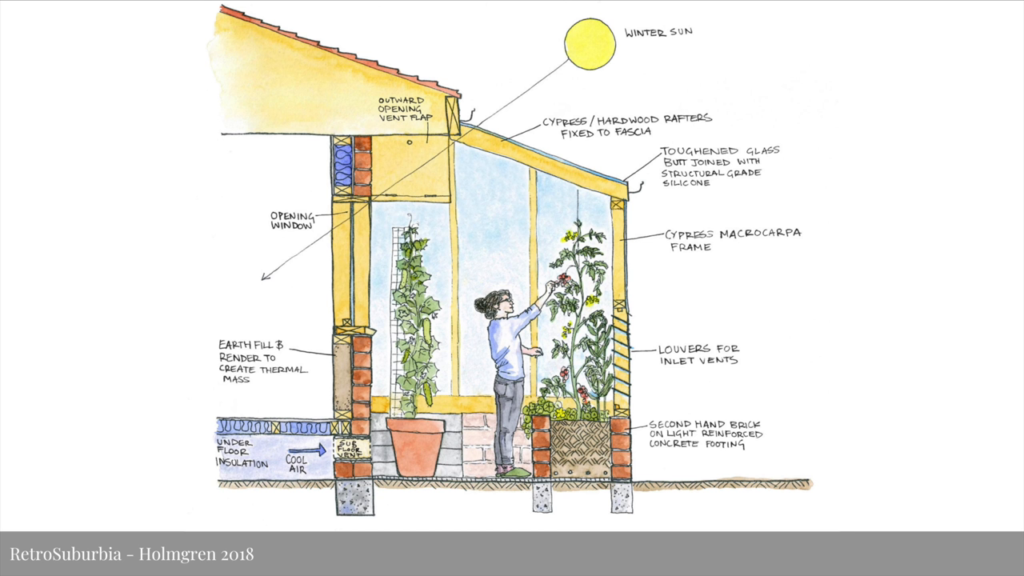

One such example is David Holmgren, the co-originator of permaculture’s newest design manual Retrosurburbia, The Downshifter’s Guide to a Resilient Future. It is a weighty tome of design patterns and mental models that can be adopted by anyone living in a city, with ideas for planting in window boxes and scaling up to retrofitting whole streets in coherent ways. It focuses on and recognizes topics such as the provision of basic needs rather than expensive wants that will dominate future policy and action; simple and robust systems that are capable of being maintained without expensive and specialized technology; progressive ruralization of our settlement patterns and processes in which biological needs and functions of food supply, water, and nutrient recycling will be fundamental to the redesigns; and relocation of our economies and decisionmaking structures.

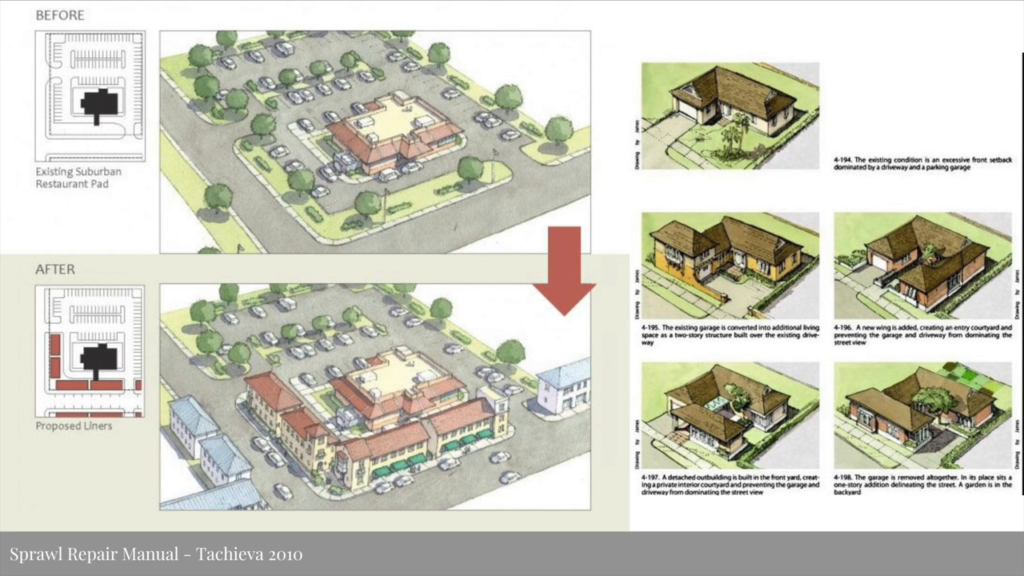

Other books such as Sprawl Repair by Galina Tachieva (I’m sorry if I said that wrong) point to design patterns that can be used in concert with Hologram’s Retrosuburbia to redesign our cities and bring about a solarpunk-type future.

Solarpunk then, should be considered a grand dress rehearsal for the future that we would like to live in, told through story, dreams, and song, aligned with the practical developments and interventions in the world that exist today as its stage.

Strategic Narrative. Unfortunately for us, to arrive at this future there is a laundry list of things that need to be reunderstood. I work professionally in and around the blockchain space, as I said earlier, and align myself completely with Jaya’s critique. So with the remaining time that I have I’d like to introduce you to my current research project, Land As Platform. It’s gonna be a book as well, and it’s gonna be a long slog to finish it.

So Land As Platform. What can we learn from the logic of platforms like Google, Facebook, and Amazon that have arisen alongside our culture of ubiquitous computation? And how could these logics be applied to our landscapes around us? Platforms are more than entities for critique, as in platform capitalism. Stafford Beer’s hugely influential book is called Platform for Change. What then in the 21st century are the kind of changes that land as platform needs to contend with?

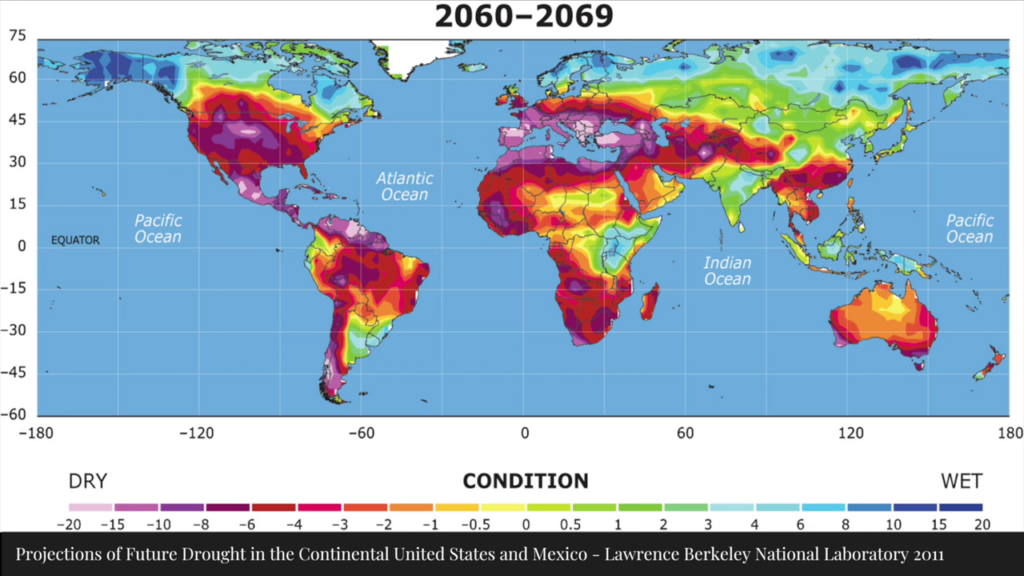

University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, Climate change: Drought may threaten much of globe within decades

Given the projected changes to our climate in the next century, and depending on which models you look at, what does it mean to imagine the Netherlands as a Mediterranean climate, or as a permanent, frozen icy tundra? Both outcomes are possibilities that require long-term thinking and preparation combined with detailed scenario planning.

So then, given the dispassionate eye that they require us to think about the Netherlands as icy tundra or as Mediterranean climate, whole climatic zones moving thousands, possibly tens of thousands of kilometers, we need to reconsider what Western ecology really means when it talks about native, non-native, and invasive species. Plants and trees will have to be moved and assisted in their relocation, just as humanity will need to be replanted and resited.

Natural personhood and non-Western lifeways will need to be reincorporated back into our culture after 500 years of intermission. Decolonizing our culture in narrative, science, and law should be considered one of the primary tasks for interested persons in the 21st century. These new landscapes will need to be designed. Ecologists and preservationists may squirm at the idea, but truly there is no such thing as nature. Not without humans present inside it. The term “rewilding” should be considered code for allowing a community of entities to unfold in place and time.

I spoke last week in Berlin at Trust, which is a new institution for platform design and utopian conspiracy. I considered the implications of deep sensing devices embedded within our environment, and the implications for these types of devices given the end of general-purpose computing and the acceleration of ASICs, or application-specific integrated circuit chip development. You can find that talk at peer2peerweb.com. It’ll be online soon.

The possibilities and questions that arise from deep sensing are question of LoNo computing, low- or no-power devices embedded within our environments, surfacing data. These devices don’t surface the data with the logic of state-like legibility and control, but as the creation of new data landscapes that a platform can contain. These data landscapes are new niches that humanity can move towards, exist in, and reacts to.

Deep sensing and embedded computing produces a further implication for how we exist with things in the world. Coexisting alongside trees, plants, rivers, mountains, deep sensing devices out in the landscape should be approached and thought about like minute bits of mountain tricked into thinking with captured lightning.

The platform, then, exists in a kind of developing present, rather than fixed to a specific idea of the future. Platforms like Facebook or Amazon, when dissected can be decomposed into modular elements that can be reconfigured and redeployed to prospect new potential lines of development. The model of a platform is to continuously flower, not control.

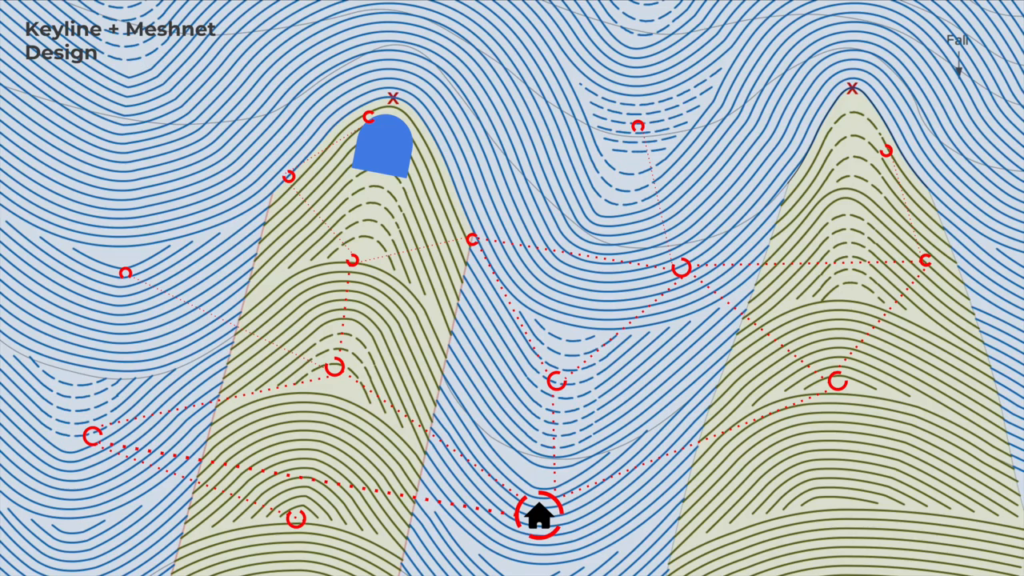

Large-scale land design projects can transform landscapes. The heavy lifting lifting is contained mainly within the planning phase. Working with local residents and planning detailed, fractal watercourses takes far longer and more effort than regenerating the landscape and planting trees itself. Does anyone know where the Loess Plateau is?

[Unidentified speaker: China?]

Yes. So, on the left is where the terracotta warriors were discovered, and on the left is what 10,000 years of agriculture will do to a landscape essentially.

So I want to consider the application of land use planning schemes such as keyline design algorithmically generated from the landscape topology, in an urgent call for holistic thinking in mesh network protocols and radio design in order to best complement the new geospatial logics of land as platform. This is a wholesale reassessment of land in the light of climate change.

Leif Weatherby, Delete Your Account: On the Theory of Platform Capitalism

Meatspace and cyberspace have fused. But platforms are still raised areas that facilitate. What does it mean for deep sensing and new landscape logics being applied at the same level of detail as we would apply building codes and zoning in cities will only further this new reality. We should be mindful of what it means for forests to own and utilize themselves, rivers and mountains to be personed, thinking machines and distributed autonomous organizations with or without others to coexist alongside one another amidst the upcoming turmoil of the 21st century. I’m not sure what it will look like, but I hope you will follow along with my work as I attempt to puzzle it out. Thanks.

![[So far,] more than 500 burners have been deployed on alpine slopes in Tibet, Xinjiang and other areas for experimental use. The data we have collected show very promising results.](http://opentranscripts.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/jay-springett-solarpunk-grand-rehearsal-00_01_51-300x169.png)