It’s really a huge honor to be here amongst all of these really incredible ideas and amazing people, so thank you very much to to PopTech. What I want to talk to you about today are two things, behavioral contagions, and causality.

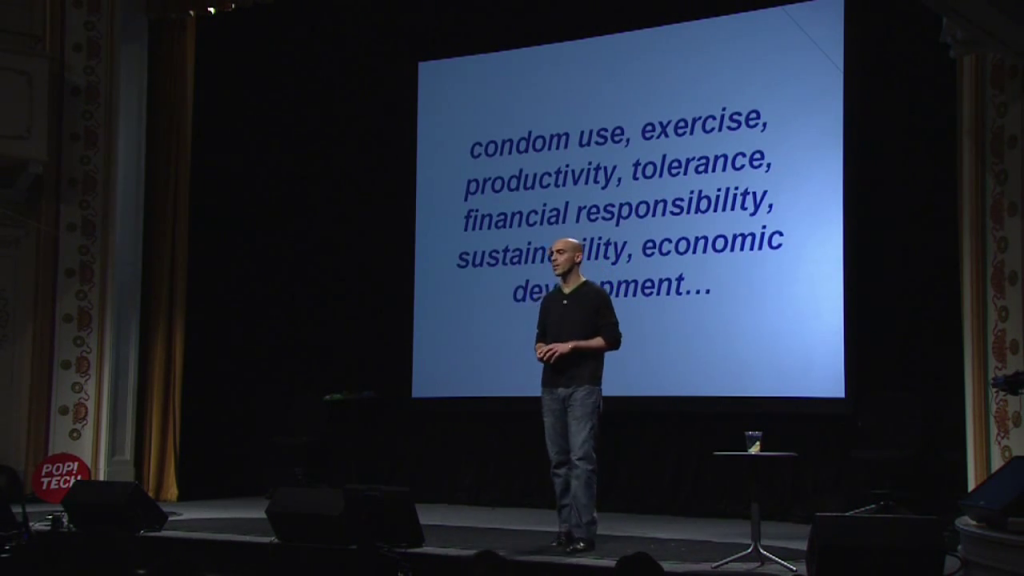

And the reason that I am interested in behavioral contagions is that I firmly believe that if we can understand how behaviors spread in a social network and thus in a population from person to person to person to person, that we could potentially promote behaviors like these, condom use, or tolerance.

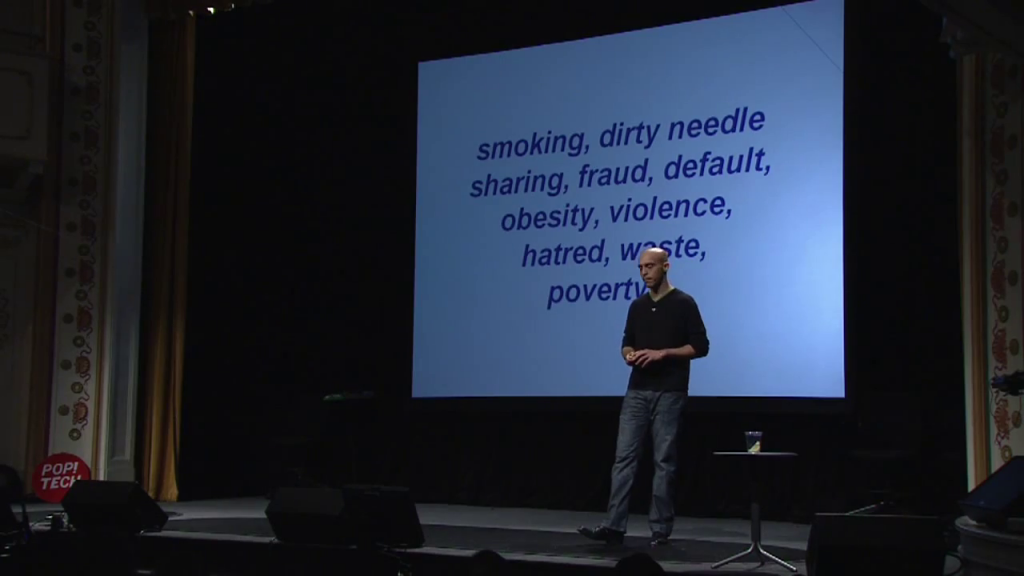

And then we can also potentially contain behaviors like like these, smoking or dirty needle sharing.

So, what I do is I mine massive social network data to understand how behavioral contagions spread in human social networks, how peers influence one another to do things like quit smoking or buy a certain product or vote for a different political candidate. And I focus on strategies, incentive strategies, to create cascades of behavior through a population. And one of the most important keys to all of these endeavors is causal statistical estimation.

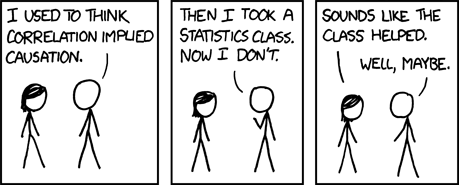

XKCD, “Correlation”

So, I have this cartoon on my door at my office. It’s two friends talking, and one friend says to the other, “I used to think correlation implied causation. Then I took a statistics class and now I don’t.” And the friend says, “It sounds like the class helped.” And the guy goes, “Well, maybe.”

And the idea is that maybe this guy has a proclivity to understand statistics and so selected into the class, and that this correlation between taking the class and understanding this difference isn’t causal. The class isn’t teaching him about statistics at all.

And in network science this is known as the reflection problem. Human behaviors tend to cluster in network space and in time. We have abundant evidence on this now. But is this because of peer influence, or alternative explanations?

Let me give you an example. James Fowler came and gave a talk here last year about his study on obesity being contagious with Nicholas Christakis. This is a great study that shows basically that Body Mass Index increases are correlated over time amongst friends. And this was picked up by the collective unconscious and by the media, and you got news stories like this one that said “are your friends making you fat?” And so, the basic idea here is that there could be alternative explanations for this. Like for example, birds of a feather may flock together. We may choose friends who are more like ourselves and thus create correlations in the behaviors amongst people that are connected in a social network.

And this is a long line of theory. This quote was originally attributed to Robert Burton in the 1500s. But it’s even older than that, because before Robert Burton it was Aristotle that was saying that people love those who are like themselves. And before that it was Plato who said that similarity begets friendship. And just to prove that it was a long line of worthy scholars who said this argument, my mom said to me, “Hanging out with a bad crowd will get you into trouble.” She was none too pleased when I told her that she might might have gotten the causal structure of that argument wrong.

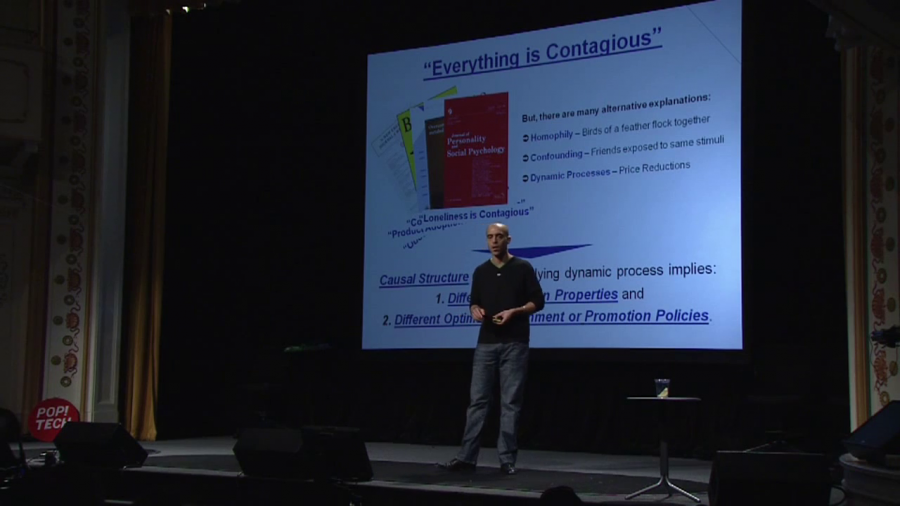

And so Slate ran an article that was titled “Everything Is Contagious” [part 2]. It’s not just about obesity. Apparently happiness is contagious, and product of option is contagious, and cooperation is contagious, and loneliness is contagious.

But it’s also not just about birds of a feather. There are many alternative explanations they can explain these correlations. Like, friends might be exposed to the same external stimuli, or have a greater probability. This is important for two reasons, because the causal structure of the underlying dynamic process of the spread implies different diffusion properties for the behavior. Where’s it going to go next, so who should we target? And different optimal containment and promotion policies. How should we design systems that prevent or promote these behaviors.

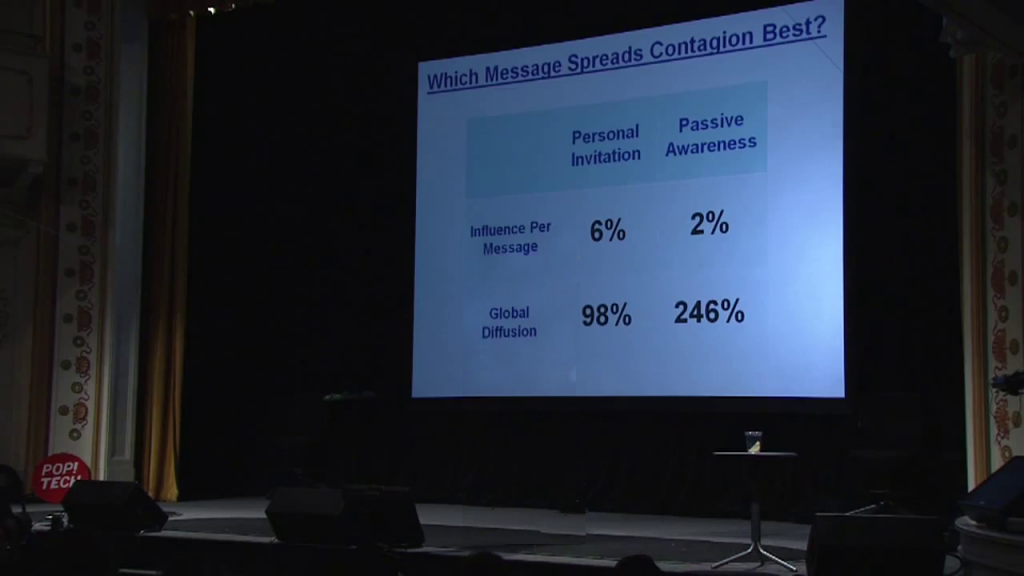

Let me give you two examples. We studied which types of messages spread a contagion best. And we studied the difference between personal invitations and passive awareness. So imagine if I gave some people the opportunity to personally invite their friends to PopTech next year, and then I gave other people in the room the opportunity to wear a shirt that said that they went to PopTech last year.

Which of these would be more effective? Well it turns out that as you would expect, the personal invitation is more persuasive. More of those people came to the behavior as a result of the personal invitation. And in terms of global diffusion, it nearly doubled the behavior in the global network for which this personal invitation was released. But in fact it was the passive awareness that generated much more global diffusion, because more people were exposed to it.

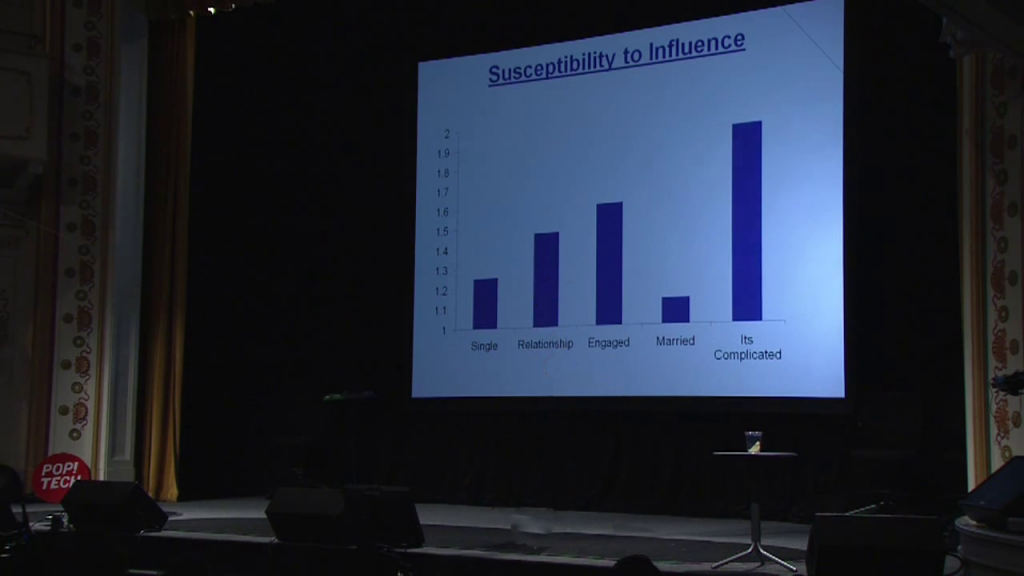

And I’ll leave you with this final result. We did a randomized trial of susceptibility to influence on Facebook amongst two million people. And initial results look like this for what your relationship status is; single, in a relationship, engaged, married, or it’s complicated. And single people are are more susceptible to influence than those that don’t report their relationship status. If you’re in a relationship you’re even more susceptible to peer influence from your peers. If you’re engaged, you’re even more susceptible to peer influence. And if you’re married, you’re not susceptible at all to peer influence, apparently. And if it’s complicated, you’re the most susceptible. So my colleagues and I debate what is going on here. And if you’d like to debate that with me or talk about any of these results, I encourage you to come talk to me. And more importantly, I encourage you to tell your friends to come talk to me.

Thank you.

Further Reference

This presentation at the PopTech site.