I’m Sara Hendren. It’s great to be here. I am an artist. I teach at an engineering school called Olin College, and I just pulled together these slides partly in response to what I’ve heard just now, because I want people to learn about Olin. It’s a tiny little engineering school. All the students get engineering degrees, mechanical, electrical, computer, software, hardware, etc. And we are by policy pretty much 50/50 men and women. We have a long way to go in terms of race or class, but Olin was started twelve years ago in part to fix [inaudible] a broken discipline of engineering, because of the vast imbalance between men and women. Nationwide the major of engineering is 80% men and 20% women, so we’re trying to reinvent the way it’s done and a lot of that, so I’d love to talk some more about that sometime.

But I’m here because my research area is in technology and ability and disability. So I’ll talk not about software in particular, because I’m not a coder or programmer, I’m not an engineer. Again I’m an artist and designer, but I want to talk about a general disposition toward ability and disability that I try to embody in my own work and the work that I do with students. That disposition is a kind of productive uncertainty in engineering and design. So whether we’re talking bout hardware or software, a kind of productive uncertainty around ability and technologies (I’ll say more about what that is.) and why would that be important throughout ability.

Well, contemporary media in US culture, and in lots of places in the world, [inaudible] pretty populated with images of prosthetic technologies and assistive devices that restore functionality to the human body by use of replacement parts and so on, and many of these technologies are fantastic. They’re very well [inaudible], right? And as a result, not a week goes by that someone doesn’t email or tweet at me something about the amazing new high-end prosthetic runner’s legs, for example, or apps for people who are blind. And again these things are great, but the problem is that these stories have an overwhelmingly monolithic narrative, and it’s the one you’re looking at right now, this kind of breathless headline about technology. So it’s like “Ooh, DARPA’s Crazy Mind-Controlled Prosthetics Have Gotten Even Better.”

My experience as a person who’s a relative of, and family member of, and friend to and ally of people with atypical bodies and minds of all kinds, I understood that this media story is really actually in sharp contrast to the wildly variable experience of people in their bodies and in their heads. So I want to encourage young engineers and designers to think about these complexities. I’ll give you a kind of example.

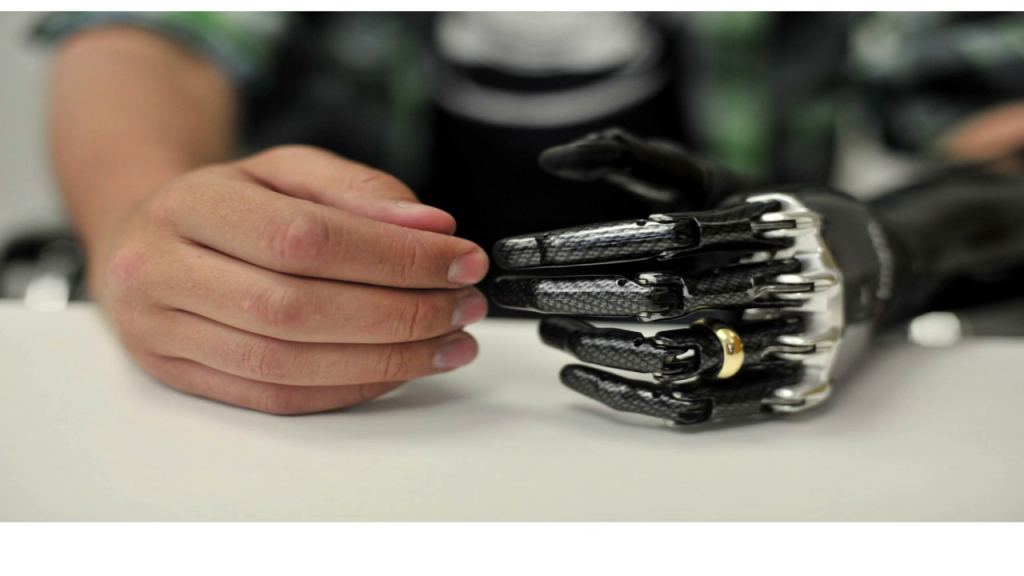

There are these really interesting technologies that you think of, that are the myoelectric hand that has fourteen grip patterns and is $90,000 and really quite impressive. Again, I think this is great. There’s a story here about returning this person’s normativity in the form of his wedding ring and so on. But things get a lot more complicated. [inaudible] not a thing you’ll see all over the newspapers, but take for instance deafness.

This is an image of a cochlear implant. Probably some of you are familiar. A tremendous amount of R&D funds have gone to creating cochlear implants which grant back some hearing to people who are born deaf. This is an entire line of engineering that’s geared toward therapeutically treating deafness as a non-normative state, but the fact is that if you go to Gallaudet University, which is an all-deaf campus, you’ll find design attention to things like this, which is called DeafSpace.

It’s an architecture precisely geared around accommodating deafness as a form of communication. The sightlines are really long (because the language is visual, after all) and these kinds of things are forking paths. There is a kind of therapeutic logic to this kind of technology, and there’s a kind of accommodating and honoring difference that goes into this kind of architectural scale systems design. It’s possible, of course, to affirm both of those things, but at some level they are in confrontation with one another, what counts as normal, what’s acceptable in the human body.

Autism is another example. [It’s] very highly contested and hotly debated, whether autism is a true disorder, as it’s often called, or whether it’s a form of neurodiversity in the way that nature honors biodiversity. Here for instance you’ll see lots of R&D and engineering research dollars going toward the development of social robots for use with children in therapeutic context. The robots are thought to be a kind of non-threatening, low threshold and remediative way to teach young people about things like facial recognition and expression and emotion and so on. Again you’ll see lots of university-based use of social robots in this way.

But there’s also been in the last ten years a really interesting development out of Denmark. A father who has a son who identifies as autistic started an IT firm that’s staffed entirely with consultants who also identify on the autism spectrum. Rather than thinking of this as a charity or a sort of special case, he built with a kind of bottom line logic a staff of IT consultants based on their cognitive strengths, not on their differences. They alert their clients to the fact that their relationship to their consultant may be slightly different than the one that they’re used to, but they promise to deliver because it turns out that in the cognitive profile of people who identify as autistic, there’s quite a lot of really strong gifts in terms of the detail and linear focus that IT requires.

So here again it’s a kind of really big distinction between turning our attention to and developing devices and products that therapeutically treat what have come to be medicalized as differences, versus systems design and institutional engineering that honors difference and in fact promotes it.

These are just two of many many examples, and the complexities are at the heart of research and advocacy that’s in what’s called disability studies. Disability studies isn’t really a field so much as it is a point of view across disciplines. But there’s a conviction in general shared politically by people in the field that sometimes people with atypical bodies and minds are asking for technologies and devices that help them gain a kind of culturally-defined normativity back. Sometimes that is the case, and so, great.

But sometimes people with atypicalities are asking for a more accommodating world, and that is I think the more ambitious challenge to the crowd who’s there today. That means systems and tools and buildings and economies, even, that honor difference. And technologies to help us ask those questions, to be provocative in the product space and in the systems space, precisely about what counts as normal, what counts as able, who’s independent and dependent, and so on.

So very practically speaking, what can young programmers and engineers do in the face of these kinds of forking paths and I think the biggest thing is to ask people themselves what it is that they want. Even in the human-centered design era, it’s still pretty rare that you’ll have people with atypical bodies and minds involved way up in the stream of research and development for technologies that are intended for them. There’s far to little of that. And honestly I think there’s too little involvement of people with disabilities in their own technologies because well-meaning able-bodies folks are nervous about doing it wrong. Using the wrong words, or general awkwardness around what to do or say, and I’ve seen this a bunch as someone who is able-bodied but a family member of people with atypical bodies and minds. I’ve seen a lot of that awkwardness, and I can tell you that that fear is often unfounded. There really are rich partnerships to be created if you seek out self-advocates and listen well and ask questions and spend time doing the research.

I think what animates me in this kind of broad notion of access and accessibility, with disability it tends to be a kind of bleeding heart issue with a lot of soft piano music in the background, and I think that’s not necessary. I think it hurts atypical people being part of the conversation. I encourage young designers and engineers to just be interested in human bodies and capacities, full stop, without a lot of preconceived notions about brokenness and wholeness, and good things [will?] result.

I do want to give one shout out to a shining beacon of an example, and that’s DIYAbility in New York. They’re a partnership between an occupational therapist named Holly Cohen and a programmer named John Schimmel, and they work one-on-one with young people with disabilities of all kinds to figure out what it is that they want to build, and they also help those young people build for themselves. So they also scaffold precisely the kind of design and engineering people can be building for themselves. It’s pretty radical and pretty rare, still. So I hope you’ll look them up.

Again, I just want to say that the need for better tools and software and design is very real, but we also need productive uncertainty about who’s asking for which kind of assistance, who’s not, and who the designer or programmer is in that process.

Thanks for including me.

Further Reference

Overview page at the Studio for Creative Inquiry’s web site.