Thanks, everyone. It’s a pleasure to be here today. I’m going to set my timer here so that I don’t run over, because that would be a bad thing. Alright. I don’t know if I need to do anything to turn myself on here. That sounded bad. But I actually mean my slides.

I’m going to talk with you tonight about the corporate control of information and why we should care. And I’m going to try to do that as quickly as possible. This is really a talk that deserves more time, and I’m so excited to be on this distinguished panel with these incredible makers and researchers as well.

The thing that is so important to me and why I study corporate control over information, specifically Google, is because in many ways, the public is increasingly reliant upon corporate-provided information. And those contexts for that provision often happen by way of alleged neutrality or objective kinds of truth that might be provided by these kinds of platforms.

Specifically, I study Google because Google really dominates the market. It’s not just a market leader, it holds a monopoly in the search space. And when you think about it, if you’re looking for information on the Web and you don’t know a specific URL, you are required to go through a broker, so to speak, or something to help you find that kind of information that you might be looking for. Those brokers are search engines. And search engines, we relate to them in so many ways. If you look at the latest research, for example, it shows that the majority of the public in the United States believes that search engines are fair and unbiased sources of information. They also think that the kinds of results that they get back (and you can look at peer research) will tell you that people feel that this kind of information that they find in commercial search engines like Google is credible and trustworthy. So this to me means that we have to pay close attention to what’s happening in those spaces.

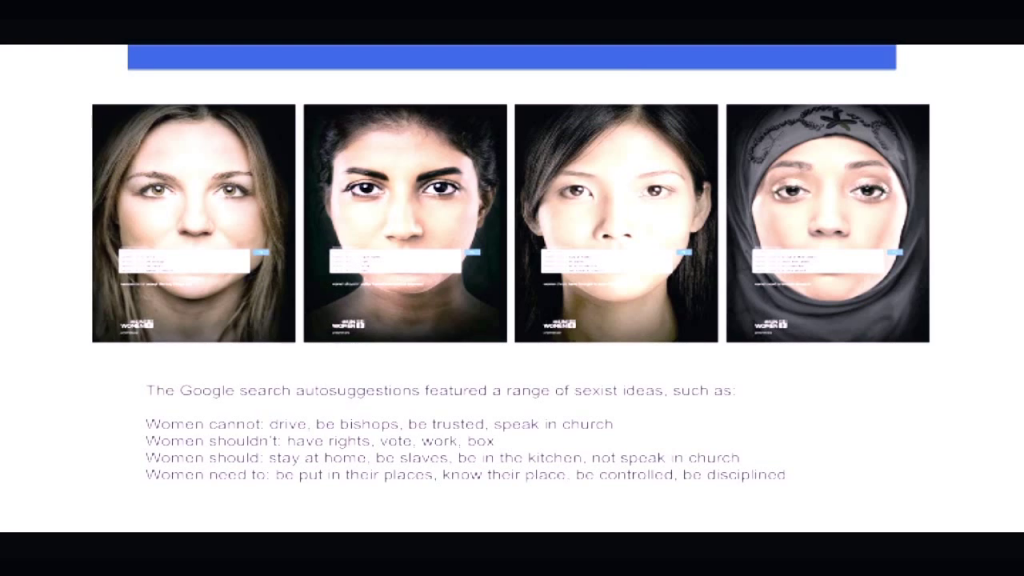

Now, some of you might be familiar with this campaign. This is one of the more popular campaigns that has come about to try to problematize some of the kinds of things that we find in search engines. This is a campaign that was sponsored by the United Nations. Ogilvy & Mather Dubai (that’s a large advertising agency) did a campaign. They did searches on various women of color, in various countries, to see what kinds of things Google would populate as an auto-suggest. What they found, for example, were things like:

- women cannot drive, be bishops, be trusted, speak in church

- Women shouldn’t have rights, vote, work, box

- Women should stay at home, be slaves, be in the kitchen, not speak in church

- Women need to be put in their places, know their place, be controlled, be disciplined

This was an interesting and fairly effective campaign in trying to point out that society holds, still, a whole lot of sexist, patriarchal values around women. But what the campaign failed to do was really to contextualize why these kinds of results come up. It left most readers of the campaign believing that search engines are simply neutral, they’re simply providing the results that are most popular or most searched on.

But I have found in my research, I’ve done quite a bit of research on collecting searches, specifically on women and girls of color. What you find is that when you start to click on these auto-suggestions, they’re linked to sites that are incredibly profitable for Google. For example, they might be linked to sites that are heavily populated by keywords that are used through Google’s AdWords program. So blogs or web sites that heavily use AdWords.

So Google makes money on the kinds of traffic that happens in relationship to some of these searches. And I think this is one of the failings of a campaign to help us understand and make sense of this commercial aspect, what the corporatization or the commercial aspects of information mean to an advertising company like Google. I often try to tell people that Google is not providing information retrieval algorithms, it’s providing advertising algorithms. And that is a very important distinction when we think about what kind of information is available in these corporate-controlled spaces.

Here’s another example. Some of you might have seen this in the summer. A very well-known Black Lives Matter activist, Deray McKesson, tweeted:

If you Google Map “nigga house,” this is what you’ll find. America. pic.twitter.com/YWRO1OiYgc

— deray (@deray) May 19, 2015

What was happening in Google Maps this summer, many people noticed, is that if you were to go into Google Maps and search on “n‑word house” or “n‑word king” Google Maps would take you to the White House. The way that this was reported on by the media, The Washington Post picking it up first and then others following, is that there must be some type of glitch in the system. And when we talk about these kinds of racist experiences and pointers that happen in technical systems, we also hear in the public discourse these things talked about, again, as anomalies, as glitches, rather than helping us to understand and unveil the ways that programmers are people who write, and code is a language. And all languages are value-laden, including binary code languages.

What this also tells us, even though Google gave a kind of non-apology, one of those “we apologize for any offense this may have caused.” I can tell you that when my husband says something like, “I’m sorry if you’re offended,” that is not actually an apology. So the non-apology apology often comes forward from Google in these cases where they might even go so far as to issue a disclaimer about the kinds of problematic search results that come back. But again, the onus is typically placed back on the user. That somehow you searched incorrectly, maybe you should’ve used different words. Never, again, pointing to the host of decisions, algorithmically, that are made to get us to these kinds of pointers. And this is really important.

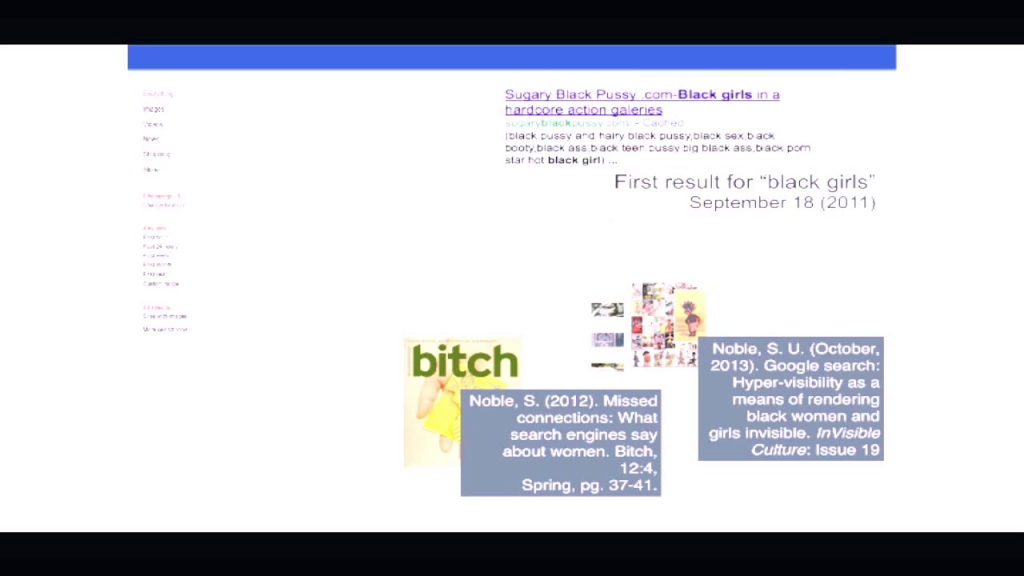

You can’t see this. I don’t know why it’s been blocked out. Sorry the image didn’t come forward, but I’ll tell you what happened here. You can see the main hit. I started collecting searches, for example on the words “black girls,” “Latina girls,” “Asian-American girls”, “South Asian girls,” “indigenous girls,” back in 2009. In 2009 the first hit when you did a search for “black girls,” and of course I was motivated partially because a colleague of mine, Andre Brock had kind of mentioned—we were talking about Google and some of the problematics. And he said, “Oh yeah, you should see what happens when you Google ‘black girls.’ ” And I was like, “What? I’m a black girl. What happens when you search for ‘black girls?’ ” And of course I have six nieces and a daughter. And what you would have seen here would be a list of highly pornographic and sexual results. The first hit in 2009 was hotblackpussy.com, by 2011 that site had gone under and sugaryblackpussy.com really dominated the landscape as the first hit when you looked for “black girls.”

Now let me say again that where the bias is is that you didn’t have to search for black girls and sex, or black girls and porn. Black girls metaphorically meant sex and porn, as did Latinas and Asian girls, and so forth. White girls didn’t fair too much better, [they] also were sexualized. And then the term “girls” really being coopted in a very Sexism 101 way because all of these sites, as you clicked down them, were not girls. They were not children, they were not adolescents, they were women, grown women. And so we have to look at these examples and say, again, what does it mean?

I first tried to write about this for Essence magazine, which is a magazine that focuses on women of color, and they wouldn’t have it because, who are you? I don’t know who you are. You can’t write for a major news outlet when you’re virtually unknown. So I thought I’d write this article for the public and I contacted Bitch magazine. They’re a progressive feminist magazine that critiques society and culture. And I couldn’t convince them to let me write this article. They were like, “Everybody knows when you search for girls you’re going to get porn.” And I was like, “Do they?”

So I said this is problematic, how girls become stand-ins for pornography, and who and how that kind of sexualization. And you can see a mapping, if you look in the porn studies literature, of the racial hierarchy as well. This kind of more violent forms of pornography and sexualization as you go through a racial order in the United States. Eventually, I told Bitch after about ten emails, “Listen, why don’t you do a search for ‘women’s magazines’ and then let me know if you find Bitch in the first five pages.” And then I got the story.

So the thing is that they understood, finally, that the concept of feminism had been divorced from women. And so it’s really important to talk about concepts, how concepts get framed algorithmically. This is a really important part of my work, and I’ve written about this. I’ve actually got a book now that’ll be forthcoming next year called Algorithms of Oppression, and it’s really to kind of elucidate how these processes happen.

It’s not just a matter of representation and misrepresentation, pornification, because that’s incredibly important. But there are other nuanced ways in which algorithmic bias is happening. Here you have an article in Forbes, a negative article that was written against a study by Epstein and Robertson, where they found that voter preferences could be manipulated quite easily based on the kinds of results that showed up on a first page of search.

So if negative stories about a candidate, especially at the local level, circulated on the first page of search, people voted against them. If positive stories circulated on the first page, people voted for them. And those things are highly manipulable. One of the things that Matthew Hindman for example wrote about in his book The Myth of Digital Democracy is this notion that what we find in these online news environments in particular is just a matter of unbiased free flow of information. He found in his research studying elections that people who had the most money were able to influence what showed up in the first pages. So this political-economic critique of what happens.

The first page of search is so incredibly important, because the majority of people don’t go past that. So what happens there is highly contested and something that we must pay close attention to.

This is one of the last things I want to share, that I recently wrote about. Again, to talk about and elucidate the way that concepts get formed and knowledge gets created and knowledge biases happen.

Dylan “Storm” Roof is an avowed white supremacist who opened fire on a church in South Carolina this summer and murdered in cold blood nine African-American worshipers. This is an excerpt from his manifesto that was found online. I wanted to draw attention to a couple of things that are really important. He says,

The event that truly awakened me was the Trayvon Martin case. I kept hearing and seeing his name and eventually I decided to look him up. I read the Wikipedia article and right away I was unable to understand what the big deal was. It was obvious that Zimmerman was in the right. But more importantly this prompted me to type in the words “black on White crime” into Google, and I have never been the same since that day. The first website I came to was the Council of Conservative Citizens. There were pages upon pages of these brutal black on White murders. I was in disbelief.

And then he goes on to talk about how could this be happening. So he talks about researching even more and this affirming his commitment to white supremacy. And he says through all this research, which we can gather much of this happened online through Wikipedia and Google, he says,

From here I found out about the Jewish problem and other issues facing our race, and I can say today that I am completely racially aware.

Now, it’s not far-fetched to know and think that many people are coming into their various forms of consciousness, not just racial consciousness, through the use of these kinds of platforms. What doesn’t happen when you go, and for example, if you look at the Council of Conservative Citizens, the Council of Conservative Citizens is a cloaked web site. Jessie Daniels writes about cloaked web sites, web sites that pretend to be a neutral kind of media, or [an] objective site, but are in fact doing something different. The Council of Conservative Citizens has a web site that just looks like a conservative media aggregator that’s feeding out news. But it’s actually a very well-documented white supremacist organization. It’s like the businessman’s KKK and has been for a long time.

What Dylan Roof didn’t get when you do searches like “black on white crime” is you don’t get a counterpoint, for example, that says “there is no such thing as black on white crime.” You don’t get FBI statistics that disprove the concept of black on white crime. You don’t get information from black studies scholars, for example, that might talk about what a framing of a question like black on white crime even means in the context of contemporary American society. So these are some of the things that I think I’m doing in my research to try to, again, make us aware of the critical importance of what these corporate-controlled information environments are about.

And I would just say that Big Data technology biases, they don’t just end in our first-world, US, Western, Global North context. Much of my work for the past few years has been about Google and misrepresentation, certainly. But if you want to extend the kinds of biases that happen in terms of political and economic policy, you can see the number of companies that are implicated in things like the extraction and mining industries, where you have some of the worst political, sexual violence happening in direct relationship to the extraction of minerals that we need for our electronics, for our technologies. Again, these things are hidden from view.

We also don’t see the incredible e‑waste, the e‑waste cities that are popping up along the West coast of Africa in Ghana. Incredibly toxic situations where people are literally exchanging their lives, in many ways, in the extraction and in the waste industries, hidden from view.

So we have to think again about in what ways are our fetishes around technology implicated in these kinds of more inhumane situations for other people around the world.

I’ll leave it there, and I’ll look forward to talking with you during the Q&A.

Further Reference

Later, there were a panel discussion and Q&A session.

Biased Data: A Panel Discussion on Intersectionality and Internet Ethics at the Processing Foundation web site.