Anne Marggraf-Turley: Croeso i chi gyd. This was Welsh. And a welcome to you in the Welsh language. We’re from Wales, where we both live and work at Aberystwyth University. First of all thanks to you all for coming, here in the hall and of course at the stream as well.

We’ll start, and I promise this will be the only bit of audience participation, just to wake you up a bit. Can anyone who’s actually seen a drone in the flesh, so to say, raise their hands, please? I’m talking about the military kind of thing and not the ones with paintballs and stuff. Actually Reaper, Watchkeeper… Okay, there’s just very few, not even a handful. Thank you.

Wales is quite a long way away from Hamburg, but make no mistake, we’re at the center of some of the most important things that are happening to all of us right now. Our university is situated just a few kilometers north of ParcAberporth, the UK’s only testing center for civilian and military drones. So if you live in the community of Aberporth, you see them flying there all the time. If you haven’t actually seen one yourself, you might be surprised at the sheer physicality of these things. They’re really big, and very loud. So you can’t miss them, and that’s the point.

Of course the ones that fly around West Wales are not armed, as far as we know, but they still manage to disrupt local communities, whether you object to the noise or to the research into remote combat and surveillance. It’s hard not to have an opinion on them. But the fact is drones spread social discord in whatever setting they’re placed. They make people act differently, which is bad news because British defense roadmaps are explicit about normalizing their use in domestic airspace. (Taken from an MOD document; a UK one.)

So we’re talking here about routine social management in the hands of the military. Arguably, the only time the military had this kind of role in the past was 200 years ago in the Romantic period, when Britain was engaged with what was known at the time as total war with revolutionary fronts. In fact, these totalizing perspectives which feed into mass-surveillance were framed ideologically in the Romantic period. Not only that, but strategies for resisting these totalizing narratives also emerged in the Romantic period in forms that exhibit suggestive correspondences with contemporary hacking.

Richard Marggraf-Turley: We’re particularly interested, and we hope to get you interested in some of these Romantic insights into the social impact of the widening state inspection on the imaginative lives of communities. This is the drone above the village effect, projected back 200 years ago.

We’re talking about communities that were traumatically divided, haunted by surveillance and by the phantom of conspiracy, and conspiracy here represents the ultimate expression of pathological, morbid self-referentiality. In fact, as we’ll be discussing, it was the Romantic poets that gave an emotional vocabulary to these issues. Also, this emotional vocabulary retains its relevance as we attempt to calibrate our own responses to widening state surveillance today, arguably at a time when the contract between the state and society is under assault in ways it hasn’t been since the 1790s.

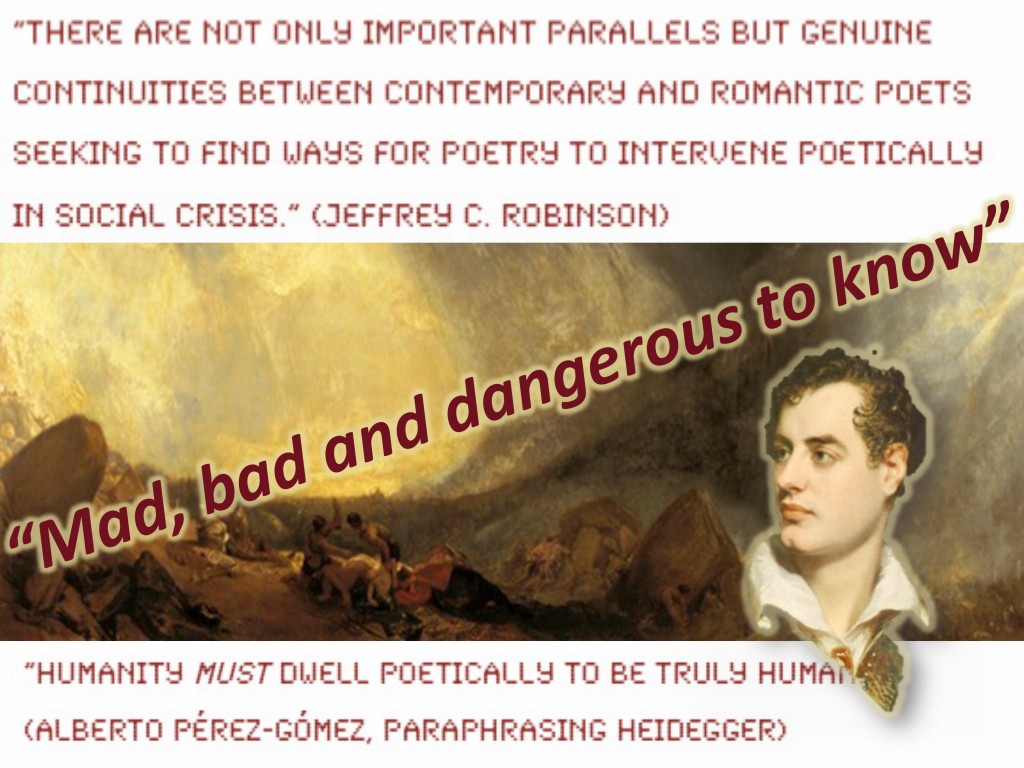

Social theory, in a sense is the intellectual child of the Romantic period, and what’s more as Jeffrey C. Robinson pointed out in a paper earlier this year provocatively entitled “Occupying Romanticism” [PDF], Romantic literature continues to identify ways in which we as 21st century citizens can intervene poetically in social crisis.

So we’ll be looking at three Romantic poets, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and John Keats, with a couple of passing references to Lord Byron. You may have heard of him. As one of his many lovers put it, he was “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” And as far as being dangerous to know goes, he would have felt, I think, quite at home with some of the speakers at this conference.

If it isn’t already obvious, we’re going to be looking at Romantic hackers that aren’t actually computer hackers. The Romantic period’s a bit early for that. Having said that, the first computer programmer, who worked with Charles Babbage on the Analytical Engine, was of course Lord Byron’s daughter, the Empress of Numbers herself, Ada Lovelace. So not computer coding then, but we are going to look at how Romantic poets use textual coding to resist the world’s first mass-surveillance state, and we’re going to suggest that their textual strategies exhibit resonant correspondences with contemporary hacking. So in the spirit of the Congress, you might say, we’re going to be crossing departments in order to trace a Romantic epistemology for practices that we file today under “hacking.”

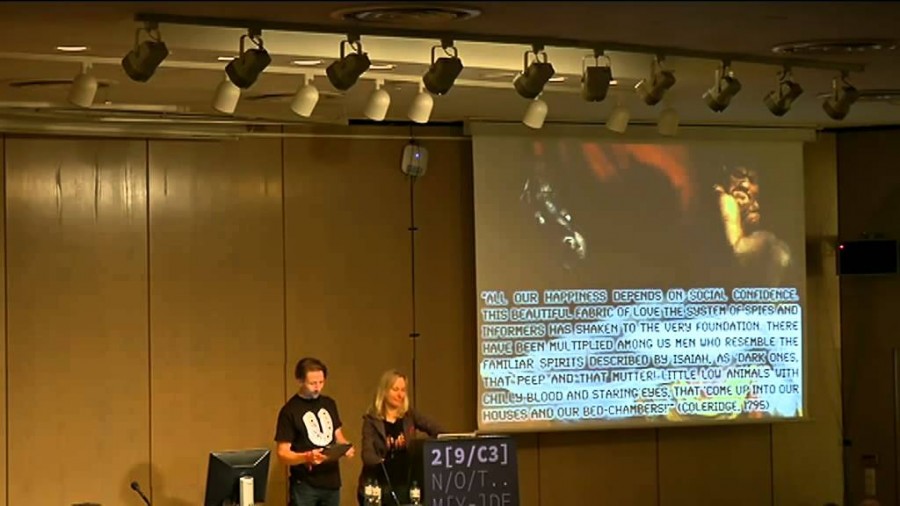

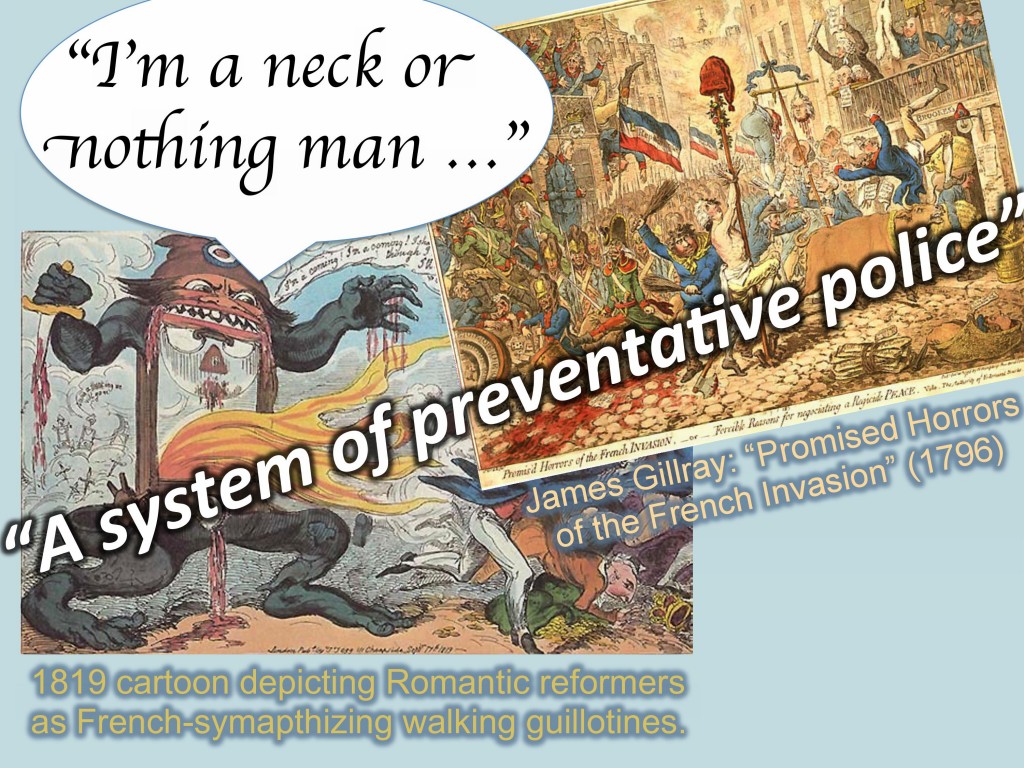

Anne: A quick sprint through political Romanticism, crash-course Romanticism. The Romantic poets were the first to have to think about communities under pressure from widening surveillance. But fear of French invasion and repressive state measures for combating spies means that Romantic poets weren’t able to communicate political sentiments directly in their poetry. We’ll talk about their hacking solutions to this problem a bit later, but first a word about those repressive measures, some of which may seem quite familiar to you from Jake’s talk.

We’re talking here about the first glimpses of the mechanisms of modern surveillance state. These two cartoons from the period frame the climate of paranoia. On the right, this is how they imagined French troops marching through London, and on the left radical reformers as walking guillotines. So open dissent in these conditions was all but impossible.

The Home Secretary’s Aliens Office introduced industrial-scale networks of spies and paid informants, with massive infiltration of political groups and routine letter interception. So the original man-in-the-middle attack, if you want. The Aliens Office even referred to itself as “a system of preventative police.”

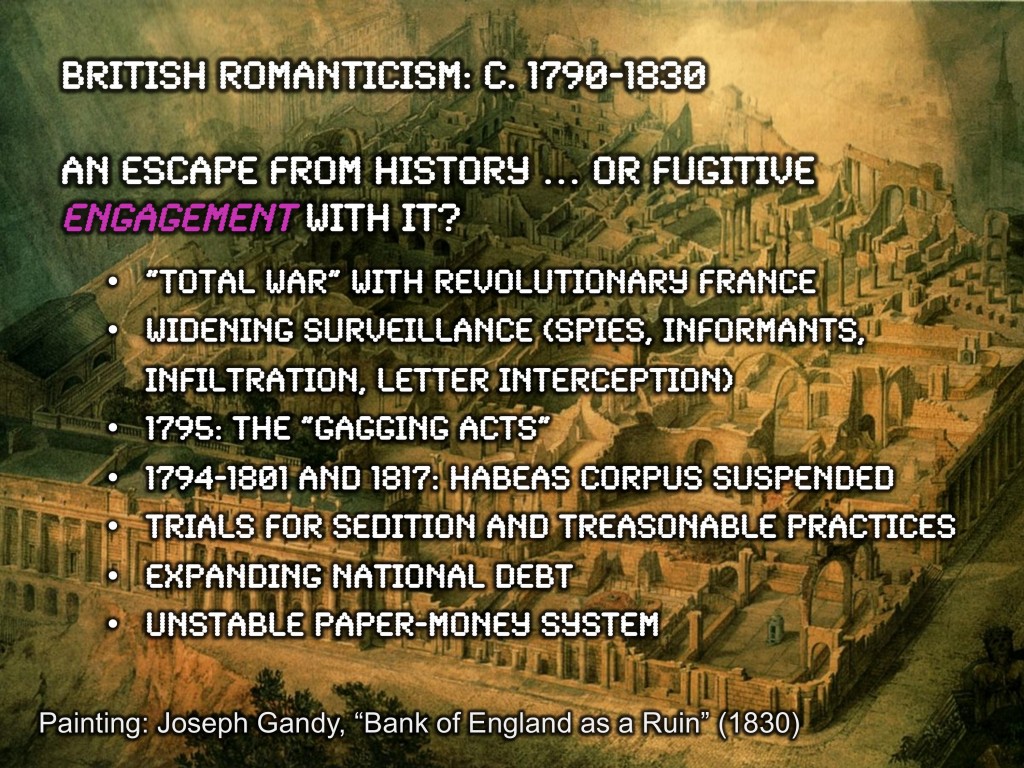

Here we are, The Bank of England in ruins, as imagined by the painter Joseph Gandy. Let’s have a look how long it takes until our bands really lie in ruins. Max Keiser thinks it might be sooner rather than later. So to summarize, in the Romantic era we have: a period of total war with revolutionary France; widening surveillance; then the “Gagging Acts,” which criminalized unlicensed political gatherings; habeas corpus was suspended twice, allowing undesirables to be detained without trial; countless show trials were held for sedition and treasonable practices; then expanding national debt; and an unstable fiat paper money system. And I don’t think we need to point out the modern parallels.

There weren’t enough police to watch everyone, but that didn’t matter. Jeremy Bentham’s great insight in his Panopticon framed a new paradigm of totalizing inspective force. While one inspector couldn’t watch all prisoners at once, the fact that the prisoner knew they might be watched was enough to “normalize” their behavior. So, we act differently if we think someone might be watching us. It’s what Foucault called the internalization of discipline.

Of course, with archived CCTV streams, ISP taps, someone is watching us. And with retroactive data mining, the modern inspector can time travel to any previous data point. So it’s vastly expanding the thirty meter circumference of Bentham’s original structure including—and this is most terrifying—its chronotope or timespace in a Bakhtinian sense, since all time becomes now.

Richard: We’ll move on to some of those Romantic engagements with the social impact of surveillance, so we’re calling this section The Fabric of Love, and it’ll become apparent in a moment why we’re doing that.

Homi Bhabha argues that any increase in the “visibility of the subject as an object of surveillance results and provokes a corresponding increase in social paranoia and fantasy.” Well, that wasn’t news to the Romantics. In 1795, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge reminded his readers that “all our happiness depends on social confidence.” Community, confidence in each other, or as he puts it so strikingly “this beautiful fabric of love” was being shaken to its very foundations by the state system of spies and informers.

Those are Coleridge’s words in 1795, and they haven’t lost any of their resonance. Where modern utilitarian fantasies of social management treat people as what Schelling calls a mechanical system of gears, the Romantic poets placed the emphasis, and insisted on, the importance of human passions and social confidence. You might say that if the logic of the totalizing state is “either/or,” then Romanticism structures itself around “and/and,” around the web-like beautiful structure, the web-like fabric of love. That’s the kind of social networking platform I’d be happy to sign up to. Forget Facebook, if anyone fancies setting up the beautiful fabric of love, I’ll be your first customer.

Anne: Let’s talk about Romantic hacking, shall we?

Richard: I hope you’re not here for the other kind of romantic hacking, by the way. Romanticism with a big R, not a small r.

Anne: Richard Stallman’s definition of hacking as “playful cleverness” informs our usage and provides a bridge between modern hacking broadly defined, and the Romantic variety as a subversion of expected norms. We’ll start with a notorious Romantic political prisoner, Leigh Hunt, poet and journalist, a friend of poet John Keats.

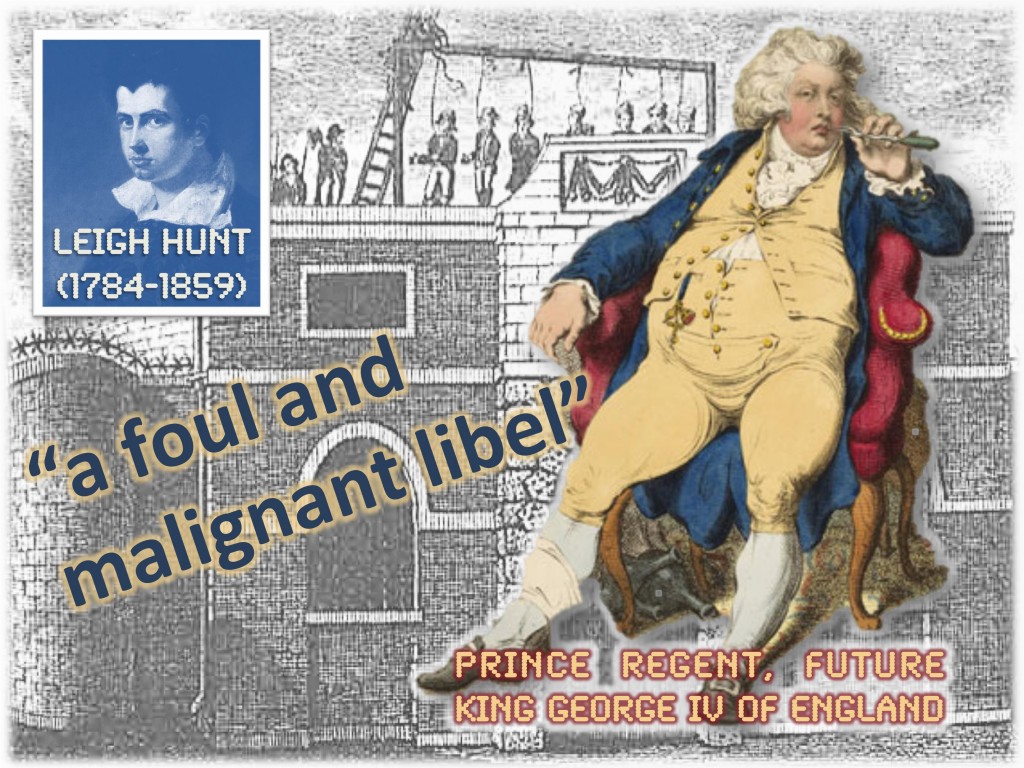

Richard: We’re going to whistle through some of these examples. That’s Leigh Hunt and that’s Horsemonger Lane Gaol. Hunt had been sniping at the government for years. He’d been exposing national debt, criminality and military mismanagement, the kind of things governments then and now like to keep hidden. He finally went too far, though, when he called the Prince Regent, the future George IV of England, “a fat Adonis of 50” in print. And in December 1812, almost exactly 200 years ago to the day, he was sentenced to two years in prison and was given a £5,000 fine aimed at shutting down his newspapers. So we’ll put Hunt in prison for his “foul and malignant libel” on the Prince Regent.

And his story should’ve ended there. He should’ve done the decent thing and caught jail fever and died. But in fact, he continued editing his newspapers and set about hacking his prison cell, an outrageous act of trolling. The first thing he did was to cover the walls in a nice wallpaper, he had a pianoforte brought in, [a] chaise longue. He had the ceiling painted a sky color, and he used to hold soirées there. People used to bring claret and they’d get drunk, and they’d agree to be locked in overnight and they’d be let out the next morning. He had Venetian blinds put over the windows, as well.

One of his visitors was Lord Byron, who dubbed him The Wit in the Dungeon. But another visitor was the man who dreamed the Panopticon, Jeremy Bentham. And Jeremy Bentham also identified him as “a man of wit.”

Anne: Leigh Hunt’s wit points up a humorous, trolling side of Romantic resilience to unrelenting surveillance, which you [can] see survives in Anonymous and LulzSec. In a sense, you could also see Assange’s incarceration in the Ecuadorian embassy along a continuum of hacked prison cells, with Romantic roots.

Hunt’s crazy Romantic prison cell reverses the dynamic of the inspective force, and so reversing the logic of the original Panopticon. Hunt’s confinement represents an anti-Panopticon. Rather than one person changing the behavior of a large number of surveilled subjects, the trolling prisoner is observed by large numbers of outside visitors, visitors who cannot fail either to notice or become actively involved in a direct challenge to inspective force.

Our second example is what you might think of as an analog trojan. Romantic radicals went underground, but we shouldn’t think they simply abandoned political activism just to write poems about flowers and birds. Rather, they hid political poems within nature poems. This is much like steganography works. Andy Tannenbaum’s well-known example shows two JPEGS of three zebras and a tree. However, one image conceals five plays by Shakespeare. Here a layer of color information has been removed and replaced with covert information.

Richard: You could apply this idea of transport and covert layers to poetic analysis. So have a look at the second stanza from John Keats’ ode “To Autumn,” one of the best-loved poems in the English language, and often thought to represent the quintessential picturesque English rural landscape at harvest time. We’ll just read out a couple of lines.

“Who hath not seen thee (thee being autumn) oft amid thy store?” And then a little further down and we’re looking now at some of the workers in the field, who are taking a nap. “Or on a half-reap’d furrow sound asleep, drowsed with the fume of poppies, while thy hook (the reaper’s hook) Spares the next swath (of corn) and all its twined flowers.”

It’s a scene of bucolic bliss and rural idyll, right? And those are hard-working laborers taking a well-deserved rest, aren’t they?

Well, actually hidden beneath this reassuring image, just like Andy Tannenbaum’s zebras, is a much more subversive message about surveillance and unrest among agricultural workers. As recent work with two friends and colleagues from Aberystwyth University, Jayne Archer and Howard Thomas has shown (you can look it up), that oddly-phrased first line “Who hath not seen thee” sounds the alarm, surveillance. Are those workers sound asleep on a half-reaped furrow because they’re taking a well-earned break, or are they rather putting their tools down because they’re poorly paid, disgruntled, disenfranchised laborers who should be working, and are sleeping in the furrows to avoid detection from the foreman? Might we actually be observing them in the act of withdrawing their labor, striking in other words, and joining wider agricultural unrest that swept across southeast England at the very time Keats was writing this poem in the town of Winchester?

Institutional accounts represent this poem, this great ode, as a vision of contented England. But given Keats’ friendship with Leigh Hunt we just saw in prison, that reading seems too simplistic. It’s much more likely that these lines capture a moment where workers are avoiding detection, putting their tools down, and it also alludes to other political poets, and Keats is advising similarly to keep a low profile in difficult times.

Less astute readers just see zebras. They don’t see the subversive message. It’s perfect encryption, and it still is. It’s perfect because really it’s a code. It’s an allegory, a political parable, and yesterday Bill Binney was talking about how he preferred codes to encryption. You can see why.

Anne: We’ll end with visual analysis techniques. Crowd surveillance, like we heard yesterday in Ben’s talk, and multiple object tracking. Again, by objects humans are meant, of course. Observe the distancing language here.

Crowd surveillance and multiple object tracking divide information into foreground and background, or space-time interest points. The algorithm distinguishes between moving and non-moving elements, and then “decides” whether the motion is predictable and explicable, normative or non-normative. This technology can already tell whether someone is drinking coffee or smoking a cigarette. As our colleague Hanna Dee from Aberystwyth’s computer science departments puts it, soon it will be impossible to leave your bag on a train.

Richard: But Romantic poetry is all about leaving bags on trains. So in a sense, which bit of the image moves and which bit remains still is as important in poetic analysis and poetic interpretation as it is in visual analysis. The trick clearly is to reverse the dynamic, and make the bit you want to keep hidden (the important bit) as still as you can.

The Romantics were already exploiting this vulnerability in discourse, in hermeneutics and interpretation. Wordsworth’s poem “The Thorn” was written in 1797 in the midst of the French invasion anxiety. Wordsworth had visited revolutionary France in 1792. No one quite knows what he was doing, but he narrowly escaped the September Massacres, and he lost a friend, the French journalist Gorsas to the guillotine. More than enough to make him an object of interest to the state.

We’re just talking there about moving and non-moving parts of a poem. Wordsworth was all over this in 1797. In fact this is exactly as he puts it in his note to “The Thorn.”

It was necessary that the Poem, to be natural, should in reality move slowly; yet I hoped, that, by the aid of the metre, to those who should at all enter into the spirit of the Poem, it would appear to move quickly.

“Note to ‘The Thorn’ ”, William Wordsworth

Pretty neat. And what’s more, those readers of Wordsworth who were willing to enter into the spirit of the poem found a radical spirit waiting for them. We’ll show you what we mean, and it’s actually quite a funny story. As in funny scary, in what surveillance does to communities. This is the background to the note published with “The Thorn.”

In 1797 Wordsworth left London, which was politically too hot, and he moved to a little coastal village called Nether Stowey in Somerset. He settled down there with Coleridge, who was also a political refugee. They were joined there by the most notorious political figure of the day, a man called John Thelwall. In 1795, he had been interrogated in the Tower of London, and he narrowly survived a trial for high treason.

Thelwall’s arrival in the village of Nether Stowey caused a storm of rumor and suspicion. And when Coleridge rather stupidly asked one of the locals whether any of the small rivers in the area could carry boats down to the sea, one of the locals assumed he was a French spy looking for ways to lead a French invasion fleet inland and wrote to London to Whitehall, to the Aliens Office, and a spy was immediately dispatched. The man was called James Walsh, and he arrived in Nether Stowey. Fortunately, he was able to confirm to his masters that the three outsiders weren’t in fact French spies, they were something much worse. They were “violent democrats” and one of them, Coleridge, was even “suspected of writing a book.” Pretty dangerous stuff.

Walsh also reported that he overheard Wordsworth and Coleridge talking about a spy called “Nozy.” Walsh assumed they were talking about him because he had a big nose but in fact, as Coleridge confirmed later, they were talking about the German philosopher Spinoza.

Long story short, in the midst of all this, Wordsworth writes “The Thorn.” And “The Thorn” is a poem ostensibly about a mad mother who’s exiled from her community for—well she’s under suspicion of having killed her child. Wordsworth’s tale is narrated by a sea mariner, a retired sea captain who comes to this coastal village with a telescope. He’s accosted by a second narrator, a shadowy unnamed figure who starts asking him questions, wants to know everything about the mad mother. Who is she, what did she do?

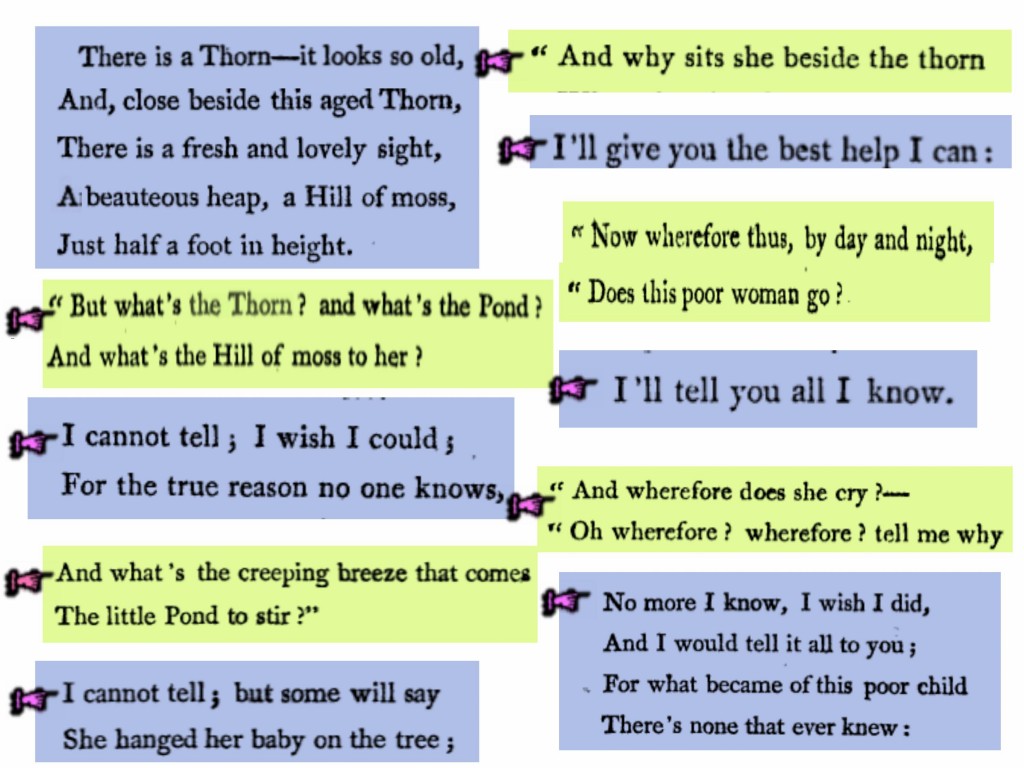

We’ve cut the poem up into its component parts, and you can see its a dialogue. Traditional Romanticism has commented on the fact that the poem seems to be structured around questions; it’s an inquisitive poem. We think it’s more than that. Have a look.

“But what’s the Thorn? and what’s the Pond? […] I cannot tell; I wish I could.” And the next one: “And what’s the creeping breeze?” The answer, “I cannot tell; but some will say [she did this].” “And why sits she beside the thorn?” “I’ll give you the best help I can.” And then down underneath, “I’ll tell you all I know.”

What we’re suggesting here is that Wordsworth is reenacting an interrogation scene of the kind that Thelwall underwent in the Tower of London, and he’s doing it because he feels guilty. After the furore created by the arrival of Thelwall and the arrival of the spy-catcher Walsh, Wordsworth and Coleridge let their friendship with Thelwall cool and Thelwall, feeling betrayed, went to live on a farm in Wales. This is Wordsworth doing penance by coming imaginatively inward with interrogation.

Anne: So “The Thorn” is Wordsworth’s profoundly personal meditation on the breakup of the Nether Stowey political community under the pressure of surveillance. The outcast mother presents the plight of the exiled and persecuted John Thelwall, and you could see her dead child as the corpse of democracy in Britain. Wordsworth makes the Gothic element of the tale the bit that moves, but the bit that he’s really interested in, politically and psychologically, is the area he keeps as static as he can. So, which agonizes over guilt, betrayal, gossip, and suspicion within the British reform movement.

Richard: So to conclude, the poem is perfectly illustrating Coleridge’s insight that surveillance destroys the beautiful fabric of love, physical communities, and communities of the mind. And Romantic poetry invites us—it challenges us, actually—to reject assurances that widening inspective force has no consequences for the innocent, however defined. Or that it is inevitable, or that it is irresistible, or that it is irreversible.

Thank you all for listening.

Further Reference

Complete slides for this presentation are available at SlideShare.

Richard has published several posts at his site related to and expanding on the topics in this presentation:

- A follow-up, Romantic Hackers — the talk.

- A second follow-up, Melting the wax … Romantic surveillance, in response to further revelations around the PRISM surveillance program.

- Melting the wax … Romantic surveillance, in some ways an early, shorter version of this presentation, though again with additional information.

- Fairy Tale Prisons… focuses on Leigh Hunt.

There’s also a short video in which he goes into more detail on Keats’ “To Autumn”