Phillip Atiba Goff: I don’t like talking to people about what I do for a living. It’s not that I don’t like my job—I love my job. It’s just it’s not always the most comfortable cocktail party reveal? Right? It’s like, “Hey, Steve. Nice to meet you. What is it you do?”

“Oh, I’m in acquisitions. Remind me what you do again, Phil?”

“Oh yeah, I’m in the ending racism and state-sanctioned lynchings business.”

“Right, right. Right. Cool cool cool. Cool. I hear that’s like a growth industry. Oh hey look, alcohol.”

Cuz the idea is it’s…it’s awkward, right. And it makes sense that it’s awkward. It’s a heavy topic, right. Because partially, the worst things that human beings do to other human beings, they often have the specter of racism on top of them. But it’s also awkward because frankly, a lot of people don’t have a lot of hope that we’re fixing racism anytime soon, particularly in the contemporary sort of political environment that we live in.

So, today I want to talk to you just a little bit about how the science of racism, how racism actually functions, can bring a little bit of hope to these difficult issues, without even needing to be especially political. And better than that, how the science of racism can lead to some actionable solutions to these seemingly impossible problems.

Alright, so what kind of problems exactly am I talking about? Well for sure, I mean…racism in education, and housing and policing—that’s the work that I do every day. But I also mean recruiting. And HR practices. And marketing, right. How we come to understand how vulnerable communities, those very communities that are the drivers of culture in every country across the world, how vulnerable communities are gonna respond to products. And to brand identities.

See, we’re not just talking about the tenth sustainable development goal. If we do racial equity right, we’ve got implications for all seventeen. In other words this isn’t just a moral issue, this is a P&L issue, right. And as markets diversify, ignoring racial equity is going to leave the competition behind in the same way that lagging on green energy and gender equity has.

So, in my everyday, I deal with racism in policing. But my hope is a little bit today you all will help me to translate from the world I live in to the worlds that are closest to you so we can transform these awkward conversations about racism, make them just a little bit less painful, and a little bit more comfortable. Okay, so can I ask you to do that with me a little bit? Yeah? So it’s okay to speak back, right. Cameras are on me. Thank you.

Alright. So, to get how the science of racism leaves me optimistic, it’s important we define that term “racism.” The most common definition of racism is that racist behaviors stem from defective hearts and minds. And if you think about the ways that we talk about trying to solve this problem, you’ll hear it. To fight racism we need to combat ignorance. To fight racism we need to stamp out hatred. Hearts and minds, right.

Now, a lot of my optimism comes from not using this definition because, and this is important, it’s totally wrong. Okay. Wrong in every way. But before we talk about the definition I do use, I actually think it’s useful to talk about how this hearts and minds definition of racism, the wrong definition, how it gets to be so sticky. How it’s so hard to get rid of. So I want to use an illustrative examples.

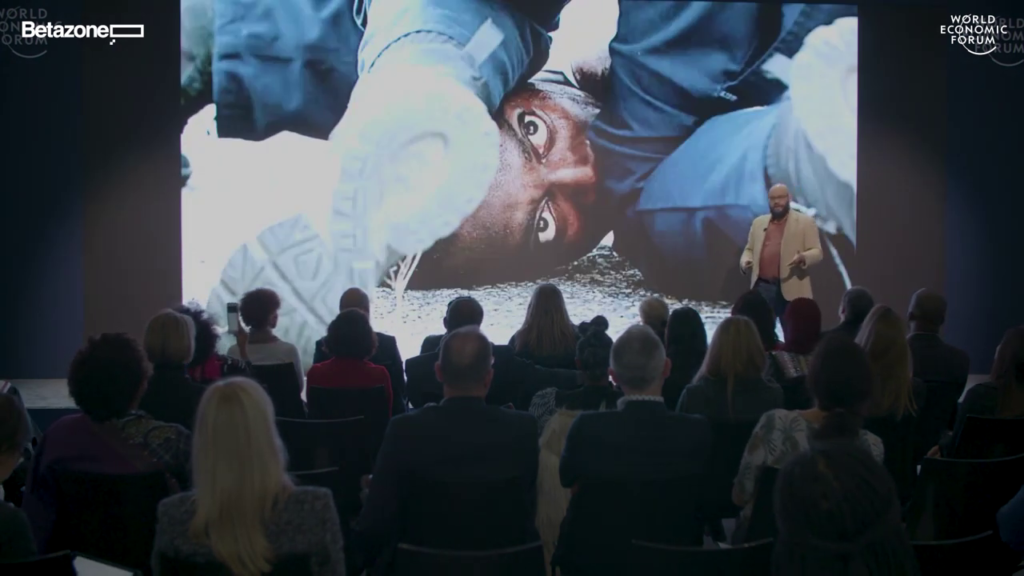

This is a picture of Emmett Till. And for those of you who don’t know where this is going, Emmett Till was a 14-year-old black boy born in Chicago, Illinois to working class parents. And as he grew up, he developed a speech impediment that made it sound like he was whistling when he spoke.

So his mother, Mamie Till, decided it’d be a good idea to send young Emmett away to live with his relatives in Mississippi during the summer of 1955. So he wouldn’t get bullied. What she wasn’t expecting is that a white woman would lie about her child.

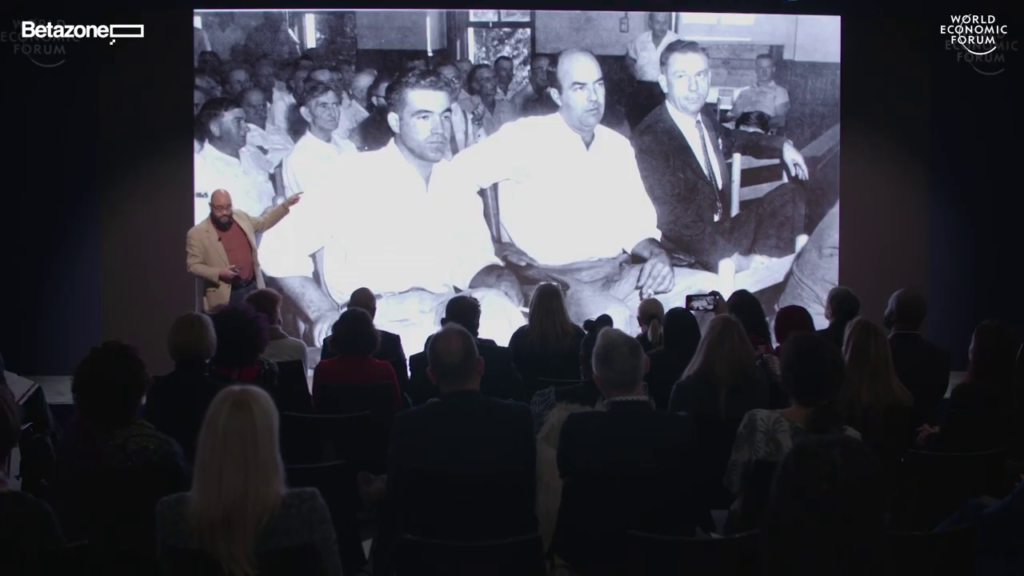

See, in August of that year, a white woman told her husband that the 14-year-old Till had sexually propositioned her. Which he hadn’t. But the result was worse than any bullying she could’ve imagined. Because on the evening of August 28th, 1955, Roy Bryant and JW Milam—these two gentleman in the white—they showed up armed to Emmett Till’s great uncle’s house. They abducted him at gunpoint, tied him up, savagely beat and mutilated his face and his torso, and when when they realized that they’d killed him they tied a cotton gin fan to his body to sink it to the bottom of the Tallahatchie River.

Pictures of Till’s open casket—and for the squeamish you might want to look away for a couple of slides. Pictures like this, they sparked not just local but international outrage. Because they shone a light on the racist, vicious violence in the United States. But more than that, by this time in 1955 there’d been over 4,000 of these kind of extralegal murders of black people, including children, since the US had abolished slavery. Four thousand.

And seeing just one image like that, one image like the lynching in Marion, Indiana, like this, where people brought their children to see this, it’s easy to imagine how you can just reduce this all to evil. This is what evil looks like. What decent person could do this to a 14-year-old boy? Our eyes convince us that something sick in the hearts and minds of people is what’s required for this to happen.

But history teaches us what our eyes can’t. Genocide, lynchings—the worst things that human beings can do to other human beings, those things happen at scale. They’re not individual—you cannot reduce them to individual hearts and minds or even a group of people’s feelings. This is not a “those people over there” problem, this is an us problem. And historians, social scientists of racism and group conflict, they’ve known that for some time. For generations we’ve referred to this as the banality of evil—it’s easy for this to happen in large groups.

So if the world has known this for some time, why is it that internationally the language for racism still reduces to individual feelings? Well as a psychological scientist, I can tell you there’s a great deal to be gained from trying to take something that is incredibly uncomfortable and make it comfortable. And our conversations about racism? They’re pretty uncomfortable, right.

So, racism is an uncomfortable topic but, if I tell you that racism is really just about what’s in your character, all of a sudden you have the capacity to be in control of that. Things you’re in control of are way more comfortable, right. Cuz if the problem really is just my feelings, then all I have to do, all any of us can do, is get our feelings right—be of good character. Because if I’m of good character I can’t be racist, when I see racism in the world, I’m not implicated. That is way more comfortable. And like I said, also wrong.

So there are two elements of that hearts and minds definition that are absolutely wrong, right. The first is that it’s scientifically garbage, and the second, it makes it harder to solve the problem. And here’s what I mean.

So for the past century or so, social psychologists have known that attitudes like prejudice are really weak predictors of behaviors like discrimination. In fact attitudes predict about 10% of behaviors, at best, through meta-analysis. But even more importantly than that, even if attitudes were great predictors of behavior, a hearts and minds definition of racism says the solution to racism is what? Salvation? I don’t know about you but salvation for me is really difficult just one on one. And it doesn’t really scale. And that’s the reason why this hearts and minds definition is a bad diagnosis. It’s not just that it’s wrong. It’s that it makes it harder to solve the problem. And worse, when we fixate on trying to change behaviors, we end up distracted by trying to rehabilitate potentially racist actors and ignoring the accumulation of harms that are happening to vulnerable communities right in front of us. By defining the problem as hearts and minds, we end up being distracted trying to fix racist people instead of fixing racist outcomes.

And I was encouraged to make all of this very difficult material accessible, so I have a meme that I think explains all of this, very simply.

Nobody wants to be this guy. Aspiring anti-racist…not changing behavior…this guy’s not a role model.

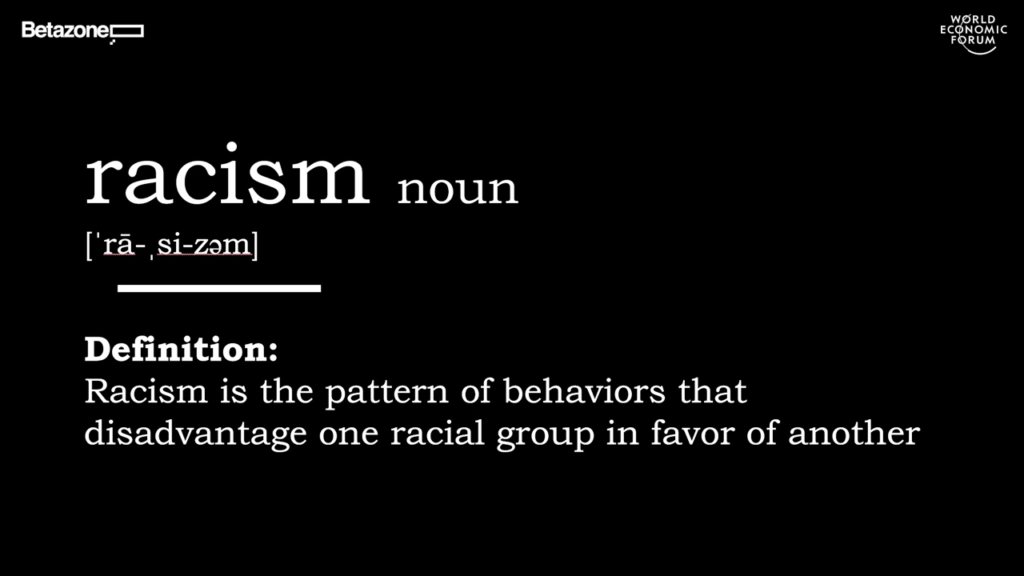

But I do have some good news. Which is that in my field, we have a different definition which is both more accurate and more actionable. As a psychological scientist we actually define racism as the accumulated pattern of behaviors that disadvantage one racial group and advantage another racial group, as well as the systems to facilitate that.

And this wonderful thing happens when you define the problem this way. You can start making it solvable, right. And when you can do that, this hopeless thing can become inspiring. And we have this great example…but mostly with sexism and corporate compensation, that comes to us from our friends at Salesforce.

See in 2015, the folks at Salesforce had a concern…right, some of you are nodding your heads—you know this story. They had a concern that they weren’t paying men and women the same amount for doing the same job. So what did they do? Well they measured whether not they were paying men and women the same amount for the same job.

What did they find? They weren’t paying men and women the same amount for the same job. So what did they do? They started paying men and women the same amount for the same job, right.

Now the surprising thing for most people is, the year later when they audited again, they found the same gender gap. Because they had acquired during that year a number of additional companies that came in with the gender gap they’d had before. So the miraculous thing that should be a surprise for exactly nobody in the entire town of Davos, the take-home message is you have to measure the things you care about, analyze them, and then optimize for them regularly. It’s called running a business with goals. It’s how every business has ever worked throughout history. We just don’t think about all of our values the same way.

So in my day job, I do that kind of thing, but for racism in policing. My center, the Center for Policing Equity, hosts the largest-known collection of police behavioral data in the world. It’s a super humblebrag but we can talk about that later, right. And we use that data to diagnose and analyze racial disparities and racial bias in police behavior, and give that back to communities and law enforcement so they can hold themselves accountable to those goals.

Now, one of the first things that people will ask me when they hear about what I do is, “Alright be honest with me, do police really want to be held accountable to data?”

The surprising answer for lots of people, is that they already do. Not just in North America, but in Latin America, Europe, Oceania, Africa, South and Southeast Asia, all over the globe increasingly law enforcement is using a tool called CompStat. Now CompStat when used properly, used appropriately, is a tool that allows you to track crime data, identify patterns, and then hold yourself accountable to public safety goals. And it usually works either by directing resources or changing behavior once folks show up. So if I’m using CompStat and I see muggings in this neighborhood, I deploy more patrols in this neighborhood. If I’m using CompStat and I find out that this community is not giving me tips anymore, they’re not talking to us, I want to change how I’m talking to that community. And when you define racism in terms of measurable behaviors, you can do the same thing. You can create a CompStat for justice.

Now, to be fair justice is kind of tricky to measure. I can’t just count the number of Asian folks who get pulled over and then compare that to the number of Asian folks who live in a neighborhood. That’s called a correlation and I’m a scientist so…I’m kind of allergic to that.

But what we can do, we can collect let’s say police use of force data. And then I can integrate that with local data on poverty, and crime, and housing inequality, and employment inequality, and health outcomes, and educational outcomes. And then when we analyze those data, we can calculate roughly the portion of racial disparities that might be able to be attributed to things that police can’t be accountable for, they can’t control. Like crime and poverty. And the portion of the racial disparities that police might be accountable for. Like their policies and behaviors. So if you wanted to do better, at least you’d have a place to start.

Let me give you an example of how this might work. In fact how it did work. In Las Vegas, we were able to look at their data and help them to see that a disproportionate number of their use of force incidents, they actually followed from foot pursuits. Now why would that be? Why would a foot pursuit lead to a disproportionate number of use of force incidents?

Well if I’m an officer, if I’m chasing after somebody, I am convinced that they are a bad guy, right. Nobody runs from the law but the bad guys; at least that’s what officers think. But I’m also running in heavy gear and polyester (not a breathable fabric). That means my heart rate is up. And I’m sweatin’ and my adrenaline’s high. That means even if the suspect surrenders at the end and say, “Please don’t hurt me,” they’re getting a shot to the kidneys for the price of making me run.

And as soon as we gave that information, just those analyses, back to the department and to the community they said, “We can train officers better than this.” Like any marriage counselor, we can teach you to count to ten. Or don’t touch them until your backup has shown up.

So the following year, across the board—not just in foot pursuit, across the board, Las Vegas Metro reduced their use of force by 23%. And in the dozens of departments where we’ve worked and we’ve employed these similar sorts of strategies, we’ve had similarly positive outcomes. So whether it’s foot pursuit in Las Vegas, or it’s immigration enforcement in Salt Lake City and Houston, or it’s the homeless problem in Minneapolis, or just low-level enforcement of low-level rules violations in Baltimore, across our dozens of partners we’ve seen an average of 25% fewer arrests, 26% fewer use of force incidents, and 13% fewer officer-related injuries. This is healthy for them as well.

Another way to put this is, if you give people a solvable problem, they’ll get busy trying to solve it. I mean, these are literally detectives, right. They’re gonna try and solve a problem you put in front of them, like anybody in any organization ever.

Just think about how this works on the flip side. How many industries talk a good game about equity, diversity and inclusion, and measure nothing. I can’t tell you the number of universities that’ve asked me to show up and look at their strategic diversity policy—which model is usually sitting right next to their capital campaign, with all of its leading metrics, right, on fundraising and success. But there’s their strategic diversity policy, and it says “We at Blank University are committed to diversity!” And that is the end of the strategic policy. No metrics, no sentiment survey, nothing, right. And I gotta say, if that is how you think about doing diversity…you’re not helping.

And I gotta say another way to think about this, I’ll let you in on a little secret. I have been black my entire life. I took like a week off in college, but other than that straight through. And I have never felt the sweet relief of justice because someone told me they were committed to feeling better about me.

Let me flip that around a little bit. That white woman whose lie cost Emmett Till his life, she’s still alive. And she recently admitted to the lie, and talked about the change of heart she’d had. How awful she felt. How terrible that was. No one could’ve deserved that.

And I ask you, does that change of heart make it better? Or is Emmett Till still dead? Because that’s the starkness of thinking about racism as hearts and minds versus behaviors. So if we’re thinking about remedies, we have to keep that in mind.

So I don’t know what remedies the people in this room, or the people who’re watching this elsewhere care most about. Maybe it’s the stuff I do every day. Great. We’ll have a great conversation going forward. Or maybe it’s the new hiring policy that has fantastic principles but no metrics attached to it. Or it’s the community engagement initiative that gives you fantastic stories, but has no clear way of measuring the benefit to the community, or to the company for that matter. Or it’s the marketing strategy for the opportunity zone with really thin KPIs. But the point that I think you’re picking up on, if an organization, if any business, hasn’t figured out how to measure the ways it facilitates racially-disparate impacts on the communities of touches, it is at both moral and financial peril, at risk. We already know this from environmental impact. We know this for economic impact. But how many environmental and economic impact plans actually have metrics built in looking at racial disparities? How much of what businesses are doing right now are designed to measure what happens to the most marginalized?

Now if the folks in this room know, fantastic. Please share. And if you don’t, the good news is that means there’s some concrete things you can do as soon as you leave the room. And believe it or not, that’s why I actually love my job. Why I think lots of people can love doing this work. Because every day, I get to wake up and try and solve a problem that most of the world thinks is impossible.

It is also why I hate talking about my job when other people think that my job is about their character. When they imagine that the racism I’m working to eradicate every day reduces to what’s in their hearts and their minds and it’s my job to tell them whether or not they’re racists.

Another little secret: I don’t care. I don’t care about whether or not somebody’s racist. I don’t want to have that conversation. That conversation is awkward, but worse it’s frustrating. And it is useless. I would much rather live in a world where our conversations about racism, are conversations about what we can do. How we can best measure the problems and deliver solutions to the communities that need them. Because solving impossible problems, for real is a growth industry. And it doesn’t need to be uncomfortable to talk about at all. Thank you guys for listening. And let’s have a conversation.