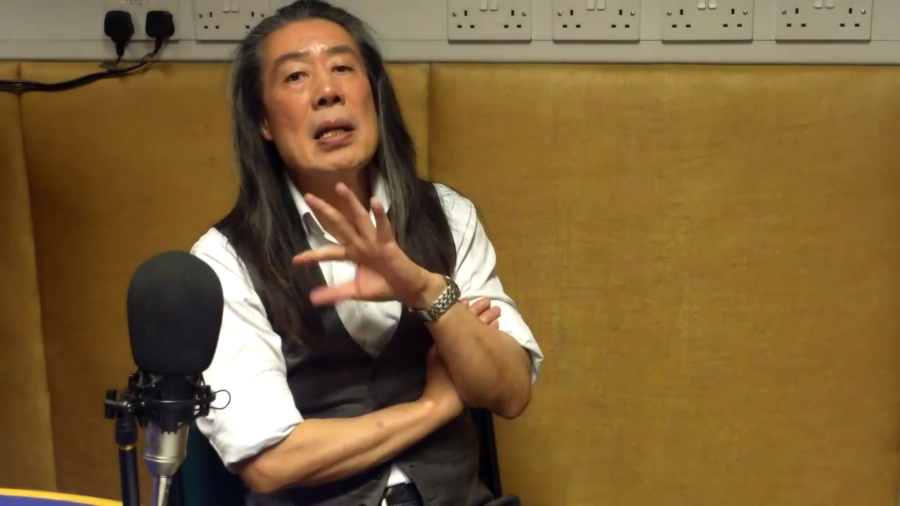

Stephen Chan: Political thought on the just rebellion, part 8. In an earlier televised rendition of these lectures, I talked about liberation theology, something which had both a religious and a genuinely spiritual element to the idea of rising up. But this idea of rising up, even when applied to the same audience does not necessarily have to have spiritual and religious elements put up front.

So today we’re going to have a discussion about what I call liberation pedagogy. And by this I mean a secular version of liberation theology which takes forward the same values. The same values of independence, the same values of creativity, the same values of the integrity of the individual person, even if that person is a peasant, even if that person is illiterate, even if that person is not fully formed in the modern sense.

In other words, talking about particularly in the Latin American circumstance about rural people who all the same have a wish to reclaim their authenticity and to create for themselves an autonomy that will withstand the pressures of modern life and the pressures of modern government that happen often to be oppressive and denying them the privilege of education. Systems of life in which schooling, in which other social provision is not available to them.

The work of people like Ivan Illich, the work of people like Paolo Freire is very very important here. The whole idea that you can gain an education, you can become an autonomous creature, an intellectually autonomous creature, even though you do not have the kind of formal education that you might wish to aspire to, even though—particularly if—you’re within a condition where society has deschooled you. If you are a deschooled person, can you be schooled in a way which is sympathetic all the same to your own experience?

Now, people like Illich, people like Freire, went to great extents to try to demonstrate that there were sympathetic pedagogies that could reach out to a peasant, to a rural population, embrace their experience, and use that very experience as a means of educating them not only towards literacy but towards self-understanding, towards being able to understand the wider world, and to be able to understand how to liberate themselves from that wider world. In other words, how to declare themselves as being within an autonomous realm not only intellectually but with the capacity to organize themselves autonomously in political terms. The “pedagogy of the oppressed,” as Freire called it, was a revolutionary statement, something which could not be made in a metropolitan country. But something which certainly had a profound influence when it was refracted back to the metropol from the experience particularly of Latin America.

There has been in more recent years, particularly as we enter the 2000s, a curious phenomenon in Latin America—in this case in Mexico—involving very key elements of what Illich and what Freire were talking about, what they tried to practice. But allied to a form of rebellion that also involved a certain military uprising. And here we’re talking about the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas Province in Mexico.

This was a very very curious combination of factors and a very curious combination of personnel. It was led, at least symbolically, at least in terms of public relations, by someone who was clearly a metropolitan intellectual. He had as it were a battle name, Comandante Marcos. He has never been formally identified, although many suspect who he might actually be. And if these suspicions are true, then he was a metropolitan academic from Mexico City.

But on camera, on the so-called battlefield, he always wore a balaclava. He also had other little tropes that he carried around with him, almost as quasi reference points to but he might be. The idea of carrying with him a little mascot, a stone tortoise which he used to stroke—a reference to the ancient Greek story that the tortoise might not be very fast but in the end it always beats the hare. The idea of smoking cigars. The languid nature of lying back in his hammock while all around shells from government forces were falling. This kind of calm amidst chaos, this kind of referencing a carelessness, built an aura—a very romantic aura—around him and around the Zapatistas who were those who were involved in helping the peasants of Chiapas to rise up against a government—a centralized government in Mexico and a provincial government in that part of Mexico, which had not provided for the rural population.

But a lot of this was highly symbolic. It was symbolic in the sense that although the Zapatistas were militarized—they were able to present themselves as a guerrilla group—there were in fact never any sustained, full-scale military clashes with the Mexican army. Everything was a polite engagement, almost as if it were scripted or choreographed beforehand. The shells would always land just short of the Zapatista encampment. The Zapatistas would never actually ambush the Mexican government. It was as were if not choreographed then a game of chess, in which one side moved to one position in such a way that the other side was able to move to another position.

This kind of symbolic military action, this kind of militarized posturing, brought the Zapatistas a certain amount of space in which they could participate in, direct, and encourage particularly a pedagogy that would benefit those who were oppressed. So that the key social services underneath the guise of launching a military uprising that was facilitated by the Zapatistas, was one of education, it was one of community organization, it was one in which the community was able to bring forward its own spokesman and spokeswoman. It was able to reference modern aspects of modernity such as gender equality, for instance. It was able to learn a voice by which the people of Chiapas could speak to the metropolitan government in Mexico City.

In a way it was a very strange development of the kinds of doctrines put forward by people like Paolo Freire. What it did was to take the pedagogy of the oppressed away from a romanticized and isolated, very very much self-contained and almost introspective view of what the world could be for those who were marginalized—in other words away from the view that you could have autonomy within your marginalization. And took it to the point where those who were marginalized could consider themselves capable of having an autonomy within the modern state.