Richard Rogers: Okay so the second presentation this morning I’m going to do. And it is entitled Platforming, Deplatforming & Replatforming. And what I want to show you is a project that I did with—some people are actually here today in this room. We did this project at the University of Bologna at the Institute for Advanced Studies. And what it is about concerns the idea of deplatforming. Extremists around the world are increasingly being thrown off of social media. And so I want to talk about—the big question that I’m going to try to answer is, is this effective? Is it good? Is it good for the platforms? For—who does it benefit? Is it good for the platforms, is it good for the extremists, is it good for the Internet, is it good for society at large? So these are very large questions, and I’m going to try to address them and give some sort of partial answers.

So this talk has three parts to it. One concerns the turn to the right online more generally. This is what I call platforming, and it’s the idea of how extremist Internet celebrities are made. Then subsequently once they have become extremist Internet celebrities, a lot of them recently were deplatformed, and I want to talk a little bit about that. And then I want to talk about their migration paths. Where they went to, and then how to map an alternative social media ecology. And I’ll talk a little bit about that as well in terms of replatforming.

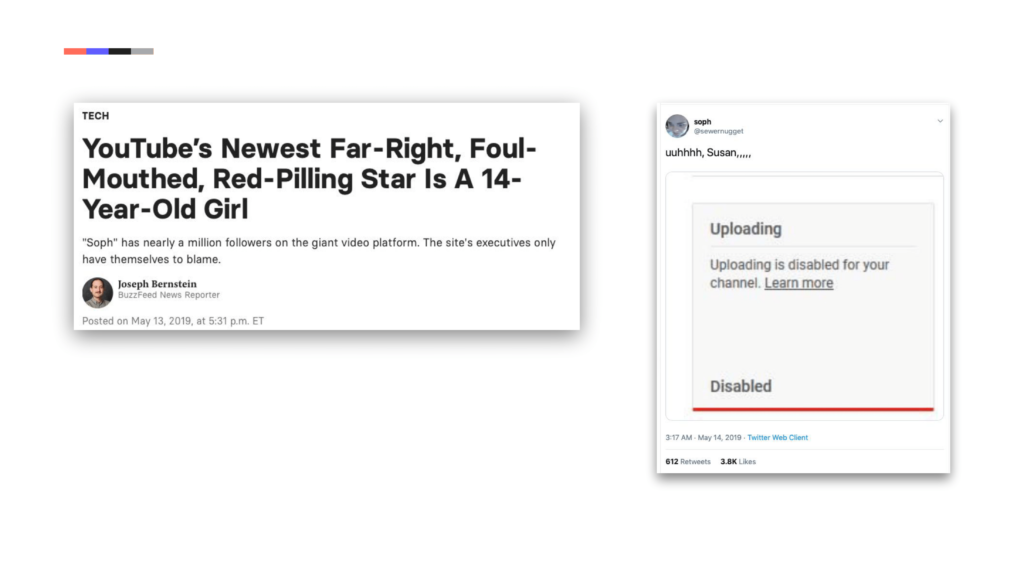

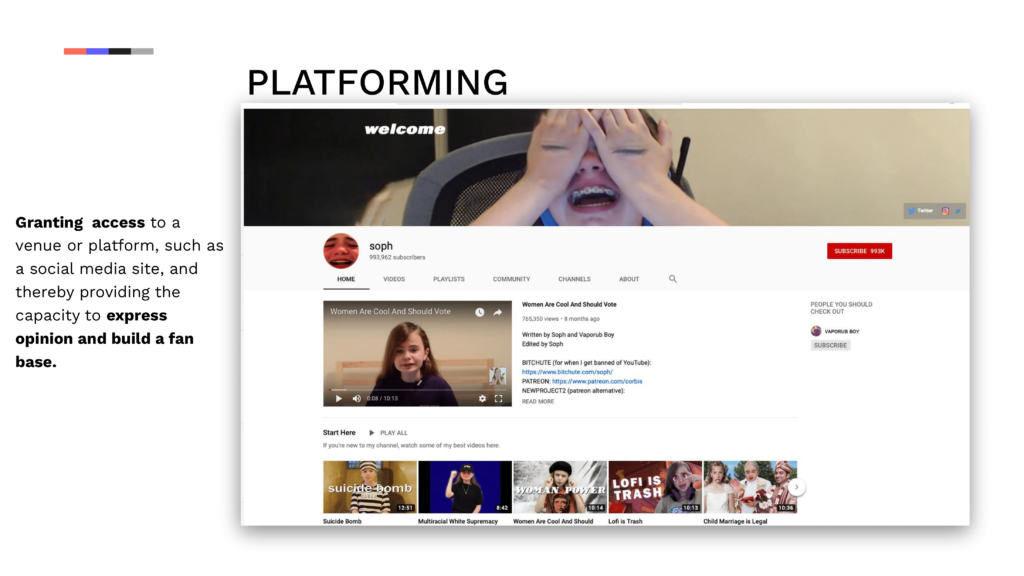

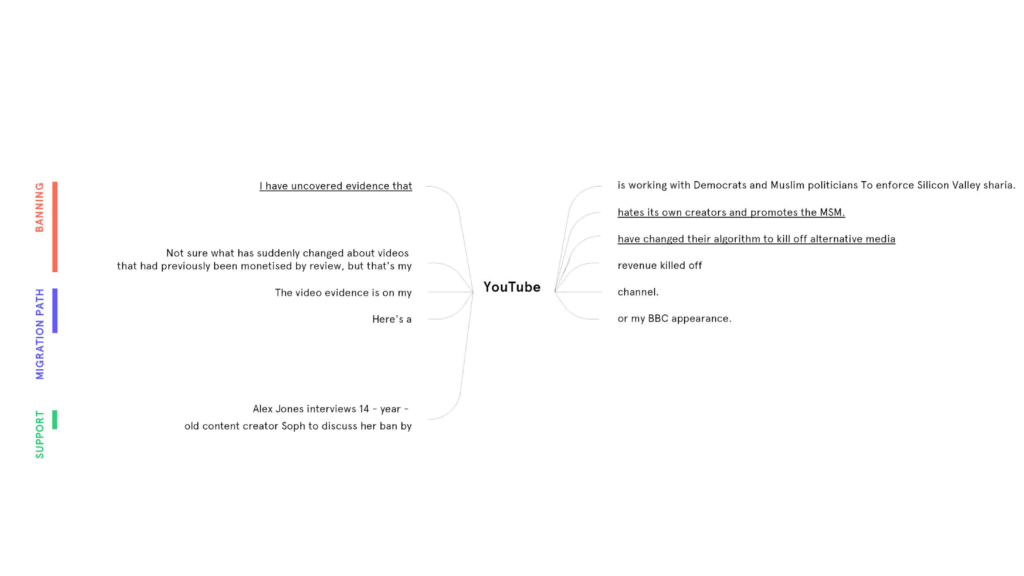

But first I want to introduce you to Soph. Soph is a 15 year-old extremist Internet celebrity. She had a YouTube channel which had nearly a million subscribers, so she was really popular. And she also had Twitter account as well that she didn’t use as much. She was basically a YouTuber. And I want to show you a video, I hope I can play it, that actually got her deplatformed. I should warn you that Soph uses quite disconcerting language. This is her merchandise to start off with.

[Rogers plays the first approximately two minutes of Soph’s video “Pride and Prejudice”]

Okay. That’s enough. Oops. Let’s make sure we close that window.

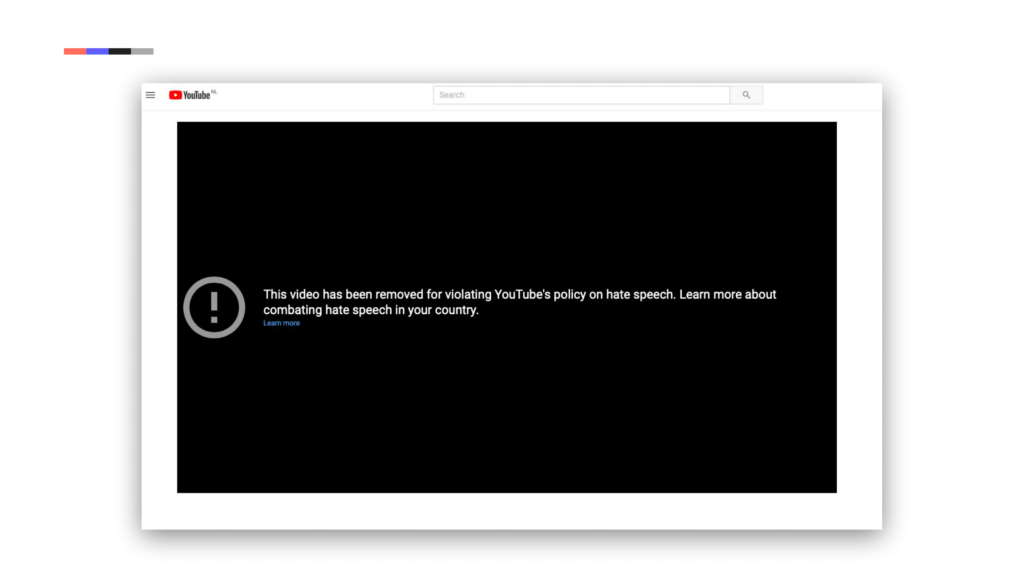

So, she was thrown off of YouTube. And this is the post on the right-hand side when she announced that. And when you go to YouTube now and click on the Pride and Prejudice link for the video this is what you get.

And this is what you’re increasingly getting on YouTube for this kind of content.

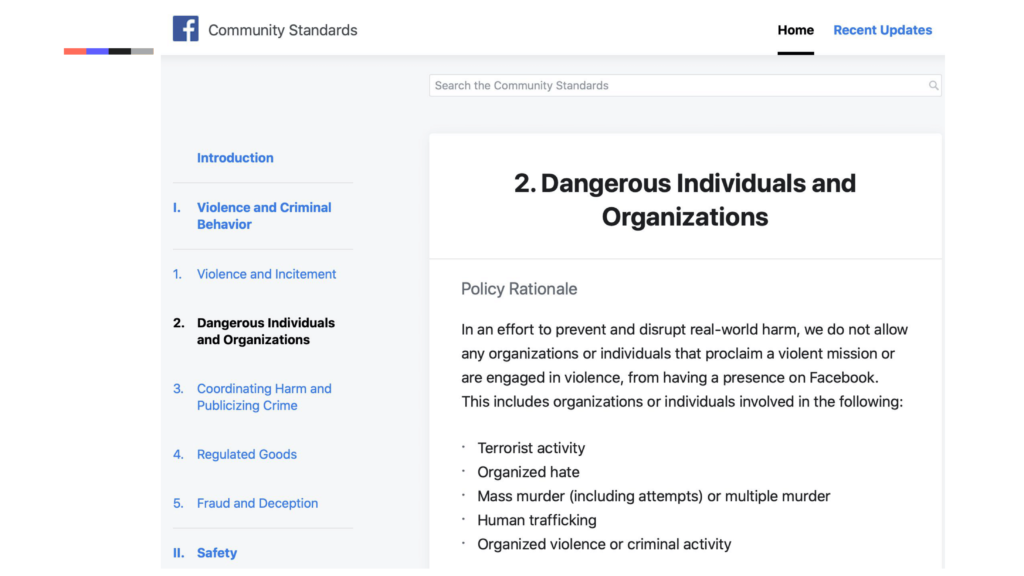

So that was a case— I mean, this is Facebook’s terms. YouTube has different ones. But these extremists are being deplatformed because they are this sort of new category that Facebook put forward, and this is the notion of the “dangerous individual.” And the dangerous individual is one who has a bunch of things, but one is that they are leading campaigns of sort of organized hate. So this is largely the rationale that’s given by the platforms.

So when in May 2019 there were a sort of series of deplatformings on Facebook in particular but also on other social media platforms, what one read both on the extremists’ pages on Facebook—which, the announcement came about a half an hour before they were actually actually thrown off. So they all sort of announced where they were going to.

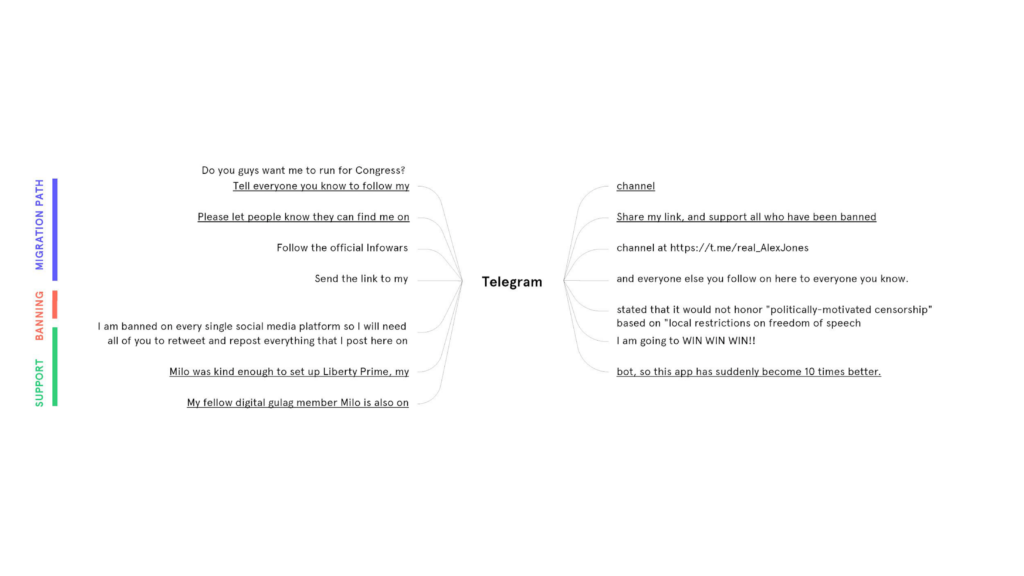

And so they announced that they were moving—a lot of them in particular were moving to Telegram. And it’s an interesting piece of software, Telegram. It was founded by the same developers who created Vkontakte, the Russian social media platform. And they were threatened by the Russian state and went into into hiding and so they were also using this particular software messaging as a means by which to show that they can do secure messaging. So they got an interesting reputation.

Telegram is a very interesting object of study. It is for what some of my colleagues here have called both for masked as well as public-facing users. So it’s sort of the opposite of Facebook. Facebook is a sort of social media platform first, and a sort of messaging with messenger second. This is the other way around. It’s a messaging platform first and a sort of social network secondly.

On Telegram you can build a following. So you can have public channels and these public channels can have very large numbers of subscribers. So this is how the extremist Internet celebrities were sort of in some ways planning on using Telegram.

It also enables what I like to call “private sociality.” So you can be social in private. So this is a little bit different from the idea that was put forward by some scholars about how people use Facebook and how public-facing users use it, this idea of social privacy. So you can have private sociality there.

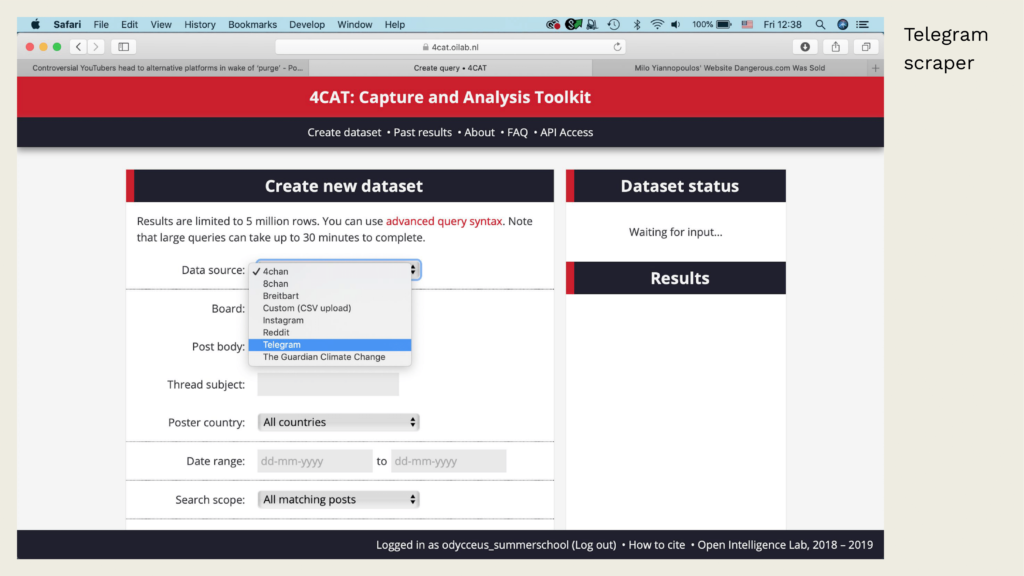

So what we did in this particular case, we considered whether we wanted to do a kind of datafied digital ethnography, or a kind of digital methods project. We decided that we could scrape Telegram. It’s interesting, when beginning to study the alternative social media platforms, these platforms are quite open for researchers. And so when we follow the extremists there, we move into a space which is not as “locked down.” So that was sort of interesting.

So we so we built the Telegram scraper into a piece of software, which will also be part of one of the tutorials today, into 4CAT in order to study deplatforming. So what is it? So once once these extremists Internet celebrities have moved over into Telegram, they were deplatformed in one and they were replatformed in Telegram, so to speak. But I first want to talk about deplatforming before going into replatforming.

So deplatforming is this idea of denying access to particular users, especially extremist Internet celebrities these days but also others, in order to hold these dangerous individuals accountable. It’s also oftentimes met with this idea that you’re also denying their capacity to express opinion. So this is a part of the debate about deplatforming. And the question is the extent to which people consider it to work, or not work.

And these are the points that are oftentimes made of why deplatforming doesn’t work. So, it supposedly draws attention to materials that are suppressed. So it makes them more interesting, because it strengthens the conviction of the followers. It creates an aura around forbidden people and ideas. And most famously I think is that we are concerned that social media companies will become sort of arbiters of speech. That they will be the ones who decide.

Whereas on the other side of the debate, which is very interesting, it is oftentimes argued and there’s some research on this, that deplatforming actually detoxes a particular space, whether it’s a subreddit—which I’ll get to the second. Other people argue that it detoxes the platform because the users do not migrate internally—they’re gone. It also thins audiences. So the audiences for these extremist Internet celebrities become drastically reduced. And then it drives these folks to spaces with less oxygen-giving capacity. So, fewer followers, fewer activity, etc.

So we decided to actually look into these arguments quite quite specifically and try to operationalize them, and turn them into actual questions. And so what we did is a number of things to try to answer these questions.

So does deplatforming actually thin audiences? Are extremists actually driven to spaces with less oxygen-giving capacity, or is there oxygen-giving capacity in these spaces like Gab, etc.? Do they become more offensive? So, in their own echo chambers, do they become even more extremist or do they mellow? Do the deplatforming platforms—so Facebook, etc.—do they become less relevant to extremists? Or are they still important? And then, are the alternative ones benefiting from deplatforming? So does Gab grow and become more important, or Telegram, etc. And then finally this sort of interesting question that we came to is, when these celebrities are leaving social media, where do they go to? I mean they go to Telegram but they also go to the Web. They go back to the Web. And the question is, is the Web being revived by this deplatforming?

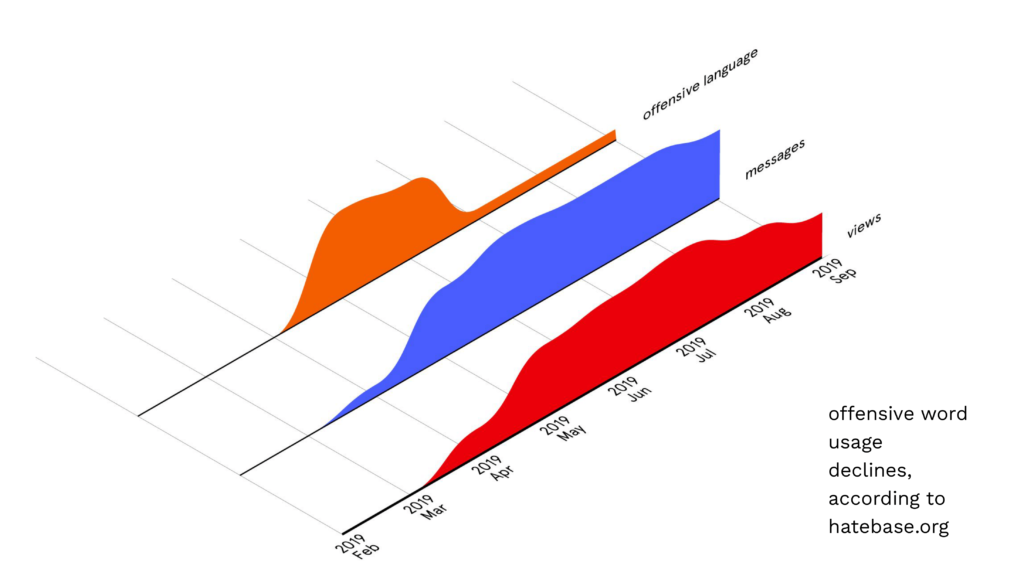

So what we did is a project where we looked at the audience counts. So, how are these extremist Internet celebrities doing in terms of their audience before and after the deplatforming? We looked at the oxygen-giving capacity through activity measures on Telegram. So how frequently were they posting, etc., were they getting a lot of views? We looked at whether their language was becoming more extremist. We did this by using sort of a hate database, a language database or a lexicon, called hatebase.org. And finally, we looked into how they discuss the platforms that threw them off, as well as the alternate platforms discursively, and we did that through using word trees and keyword in context, etc., and I’ll show you that briefly.

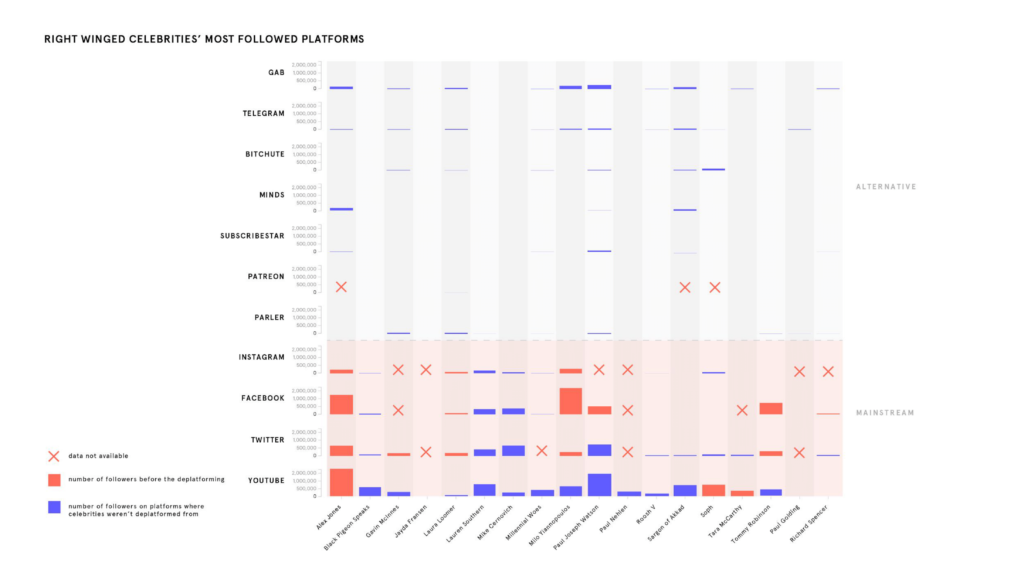

So does deplatforming thin audiences? The answer to this is yes, and quite massively. So we saw a steep reduction in audience numbers overall for about fifteen extremist Internet celebrities. So before, they had quite large audiences, especially on YouTube but also on Twitter and Instagram, when they moved to the alternative—Gab, Telegram, BitChute, Minds, etc.—their audience counts really dropped off.

But even though they may have dropped off, did these new audiences provide them with oxygen? In other words, did the extremists still continue to post with great frequency, and were they viewed also with high counts. What’s interesting is that the extremist celebrities continued to post, very very frequently. So they were acting as if they still had a lot—not only a lot to say, but a lot of view counts. And what’s interesting is that it seemed as if they were getting…well at least they weren’t decreasing in their activity. And so perhaps you could say that they still had quite a lot of oxygen in these new spaces.

What we found, however, when looking into whether they became more extremist in their language use was we found that they became a bit more mellow. So whilst they continued to message quite a lot, or post quite a lot, and their view counts were increasing—although they did decrease a little bit towards the end of this period that we looked into from May to October 2019, the use of their language was quite interesting. So it became more mellow. And this is also something that is of interest to us.

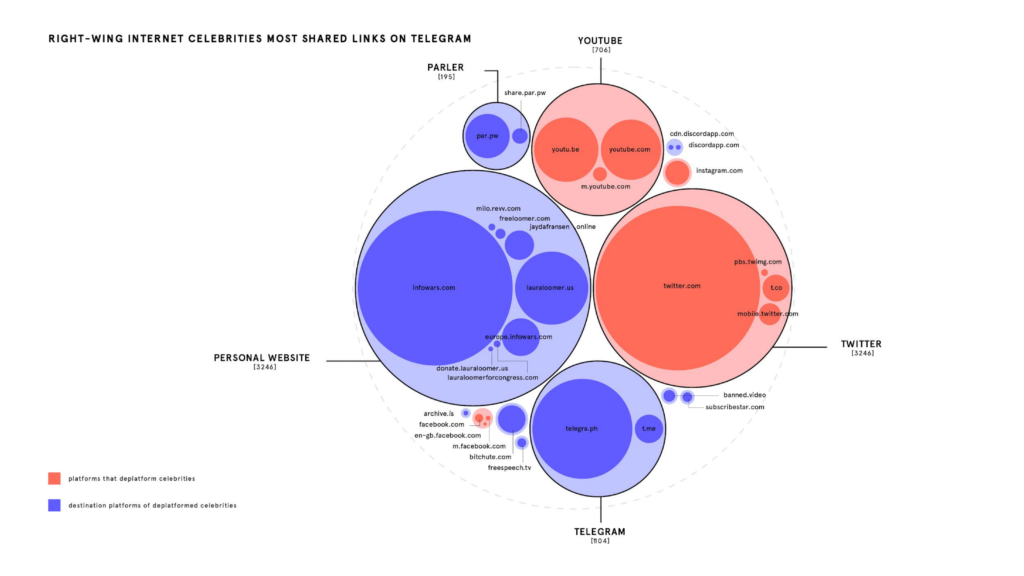

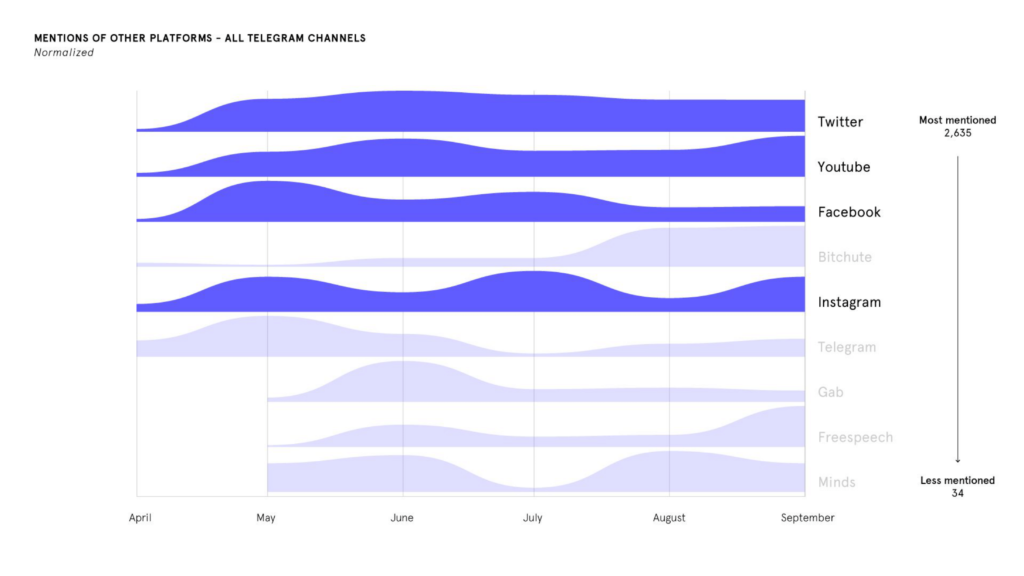

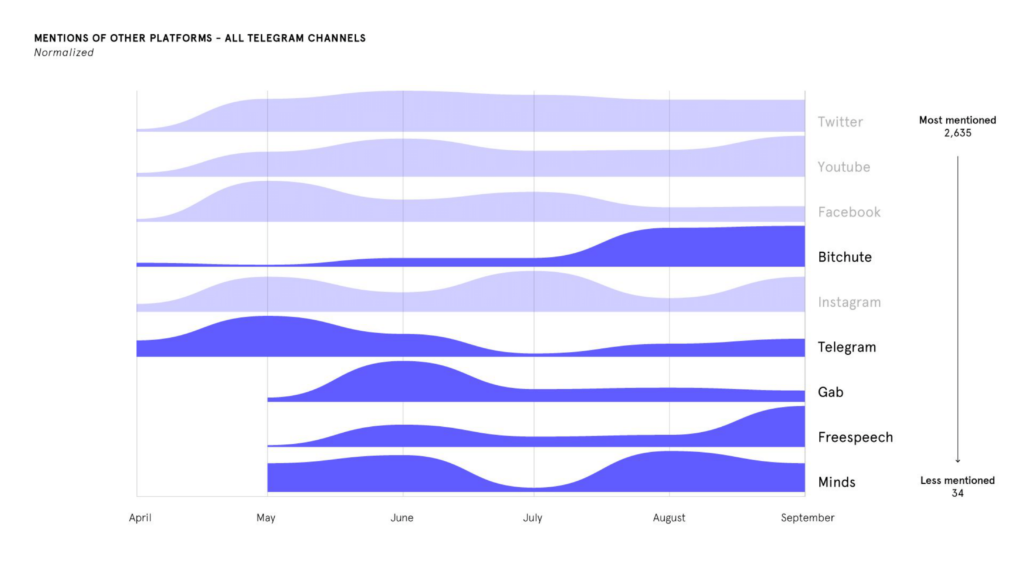

And then what about the platforms that they were deplatformed from? So Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter, etc. Do they become less relevant to the extremists? And therefore is deplatforming good for the platforms that throw them off? What we found that was very interesting to us was that Facebook and Instagram suddenly were not linked to very often, or they weren’t mentioned. So it seems as if Facebook and Instagram became far less relevant to these celebrities than they were before. However, Twitter and YouTube remained extremely relevant even though they were thrown off from there. So deplatforming might be good for Instagram and Facebook, but not necessarily so much for for Twitter and YouTube. They still are highly relevant.

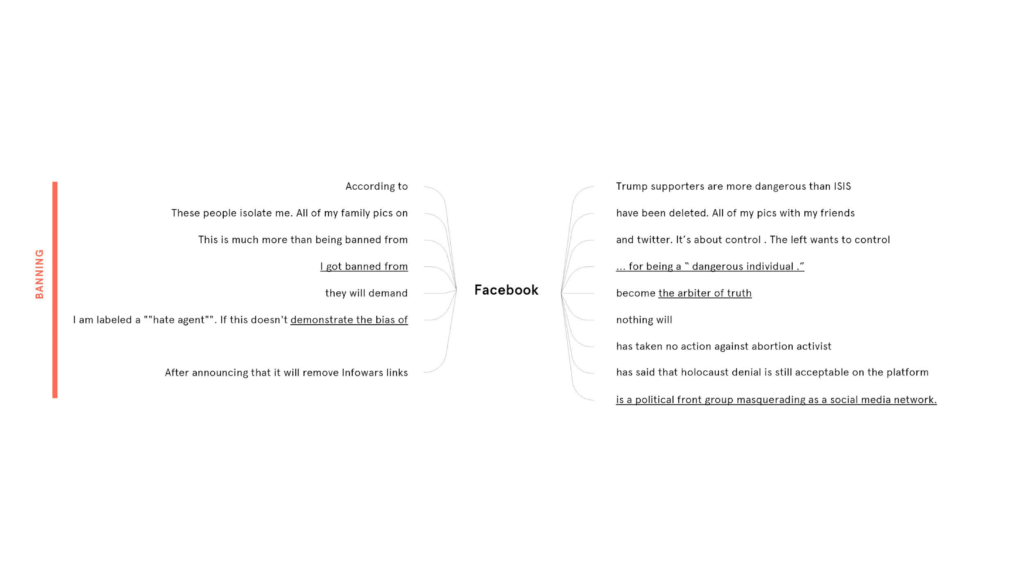

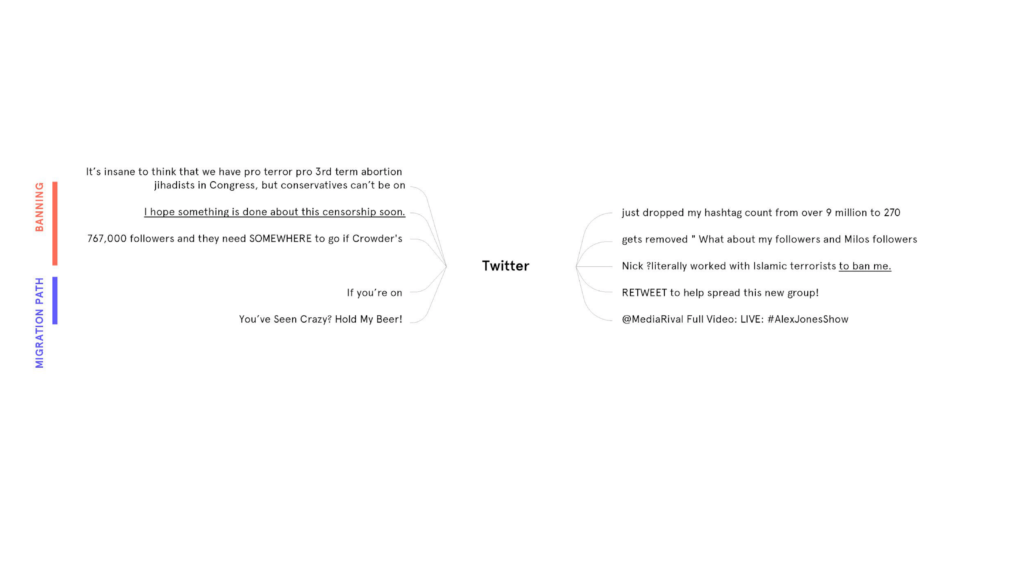

So why is it that extremists still are very interested in YouTube and Twitter, and not in Facebook and Instagram any longer, we looked into that as well, discursively. So, we downloaded all of the posts by the extremist Internet celebrities on Telegram, and then we queried these for the names of the platforms, both mainstream platforms as well as alternative platforms.

And when we looked at how they discuss Facebook, it’s all about disgust. So it’s all about how Facebook is no longer relevant to the extremists.

And when we looked at Twitter, however, whilst they’re unhappy that they were deplatformed from Twitter they still urge their other users to tweet about them on Twitter and to continue to use Twitter. So Twitter remains relevant whereas Facebook does not.

YouTube also remains relevant to them. And it also continues to be a space where they want to appear. They want to be cohosted or they want to appear on there. Or otherwise they’re still sending traffic to YouTube by discussing others who are still on YouTube.

And the question of the alternatives. So which of the alternatives, or are the alternatives benefiting? Are they growing? Are they becoming more significant because the celebrities have moved there and been deplatformed? And how are these extremist celebrities talking about these platforms?

Well what’s interesting is most all of them—so BitChute, Gab, Minds, Parler, all of them—are being used instrumentally. So they’re just trying to point their users to them.

Whereas Telegram… So this is an example. So “just go to BitChute because because YouTube is censoring our material.” And that’s also where Soph’s video that I just showed you is located now. It’s on BitChute. But all of the mentions of these alternative platforms are are basically instrumental. Same with Gab. So it’s just, “I’m on there. You can go and follow me there,” etc.

Whereas Telegram is kind of different. They feel as if Telegram provides them with a kind of soft landing spot. A place where they also communicate with one another, etc. So Telegram has a special place for these extremists.

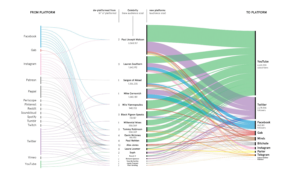

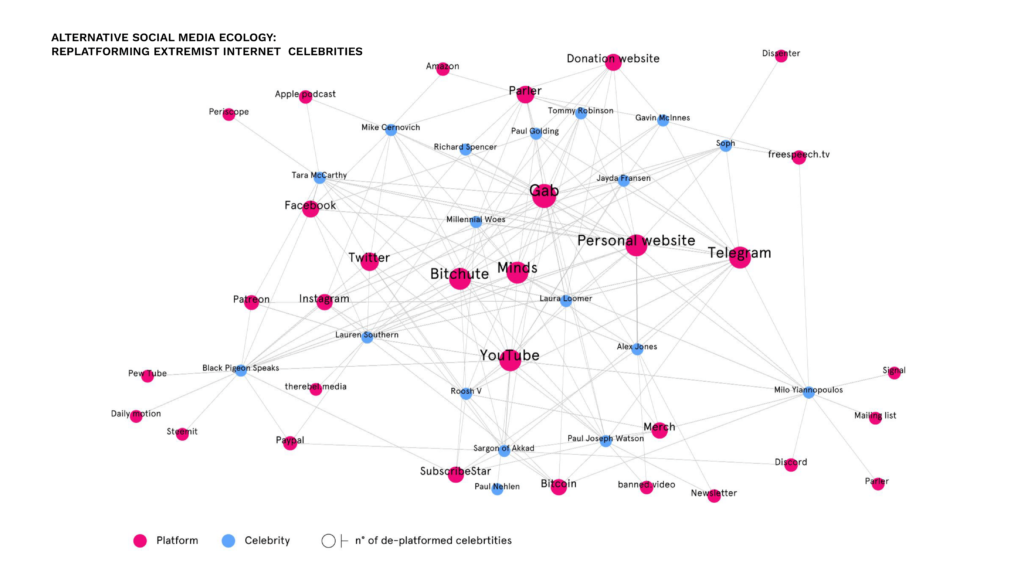

So we then endeavored to try to make the kind of “first” map of the alternative social media ecology after deplatforming. And so we did this basically manually. So we took about twenty extremist Internet celebrities and looked for which platforms—mainstream platforms—they’re still on, and which ones that they’ve migrated to and then created— So this is the alternative social media ecology at least according to the sort of fifteen or twenty extremists Internet celebrities that were deplatformed in May 2019. And what’s interesting about it is— And other extremists that weren’t deplatformed, that’s why you see some of these mainstream ones there. So, you may have been deplatformed from Twitter but not from YouTube, etc. So this is why the mainstream ones are there.

So YouTube is still quite central. So is Twitter. But you see like Facebook and Instagram are quite marginal. You also see that Telegram, BitChute, Minds, Gab, they’re quite central. But also you see personal web sites as also being quite central. So this led us to the sort of strange thought of ironically… So if social media killed the Web, when they deplatformed extremist Internet celebrities and these celebrities sort of go elsewhere, they’re now going back to the Web, in some sense reviving it.

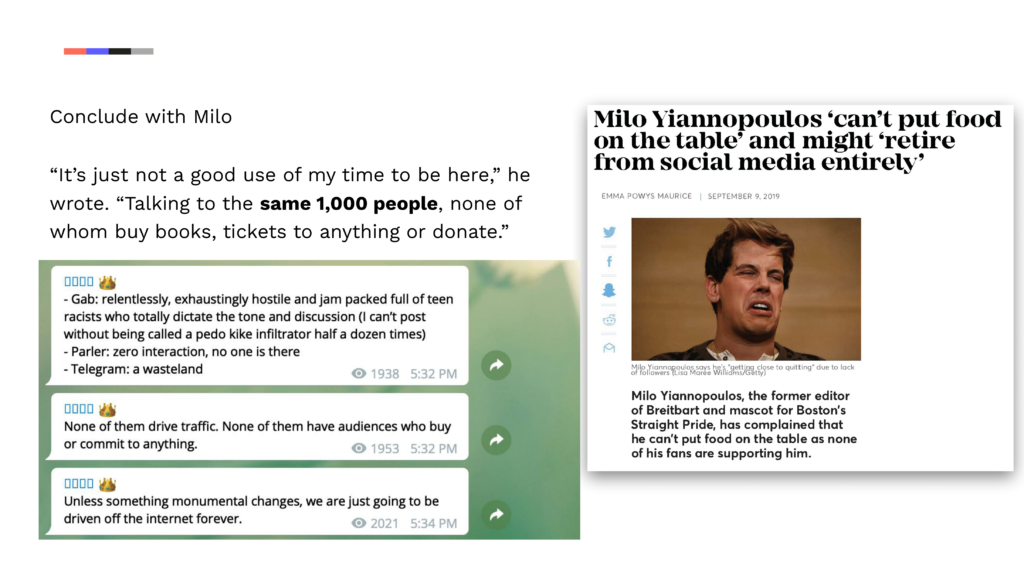

I just want to conclude with Milo. He’s quite a famous sort of alt-right character. And he has a lot to say about various platforms after he’s been deplatformed from from Twitter and Facebook and Instagram. So he is not happy in this new space, in this new alternative social media ecology. He “can’t put food on the table.” He talks about Gab as “relentlessly, exhaustingly hostile and jam packed full of teen racists.” He talks about Parler as “zero interaction, no one is there.” He talks about Telegram as “a wasteland.” He says that he might have to leave social media altogether.

So this is to some sort of quite hard evidence that deplatforming in some sense “works” or is effective. We looked at it of course more empirically. But the larger question of whether it’s good for— So it might be good for certain platforms. So it appears to be good for Instagram and Facebook, not necessarily so good for YouTube and Twitter. It’s not that good for the alternative social media platforms, with the one exception of Telegram, at least according to our empirical work.

But does its benefit society at large? This is something that we didn’t get into. We discussed so-called “cancel culture” and the extent to which this canceling of extremist celebrities by social media companies like the canceling of a television program, whether such cancel culture is good for society or not, we left that larger question open.

So social media platforms have made these “extremist” celebrities in some ways, and now they’re unmaking them. And it seems to be—as I mentioned before, it seems to be effective for certain of these mainstream social media platforms, and not for others. And what we find interesting in the replatforming and their move to the alternative social media ecology and also their move to the Web is the question of whether they’re mellowing. And we found that their language became less extreme. Maybe as Milo said it’s because the spaces that they went into themselves, those spaces were more extreme, even. So that was one interesting question of whether the mellowing, the general mellowing of these extremists in these spaces could be said to be an indication that it’s sort of good for the Internet, good for the detoxification of the Internet. However, they are moving a lot of their vile content to the Web and creating a sort subscription platform… They’re also beginning to use the Web again as a kind of toxic space, so in that sense it might not be so great for the Internet. That’s it. Thanks very much.