Julia Reda: Hello everybody. It’s a great pleasure for me to be here. I’m Julia Reda and I’m one of the representatives, one of the elected members, of the European Parliament, which is the legislative body of the European Union. And when we’ve been hearing some of the areas where defiance is happening, probably not everybody is thinking of politics as the first area. It’s rather that most of the defiance is kind of happening in opposition to politics and governments. And so I’m really glad that I still get the opportunity to speak here. And the reason for that is probably that I represent the Pirate Party. And that name alone probably tells you a little bit about our relationship to political authority.

The Pirate Party indeed did originate out of a movement that was breaking laws quite openly. It’s coming from a tradition that started more or less into the early 21st century. It’s quite a young movement, maybe ten years old. And it started out breaking copyright laws, challenging how established laws were working in the Internet or how they were not working. And maybe it wasn’t that political at the beginning, but was developing in this direction when the pirates started opposing some of the measures that were put in place to counter, or that were justified by fighting against copyright infringement but were quite often threatening fundamental rights, especially on the Internet. And then kind of really found its way all the way to the establishment, including the European Parliament.

So, the story starts more or less around the time when Napster was a big thing. Some of you maybe remember this. In the early 21st century, the Internet had suddenly become this thing that was accessible to large parts of the population. And it suddenly made it possible to copy information, cultural information as well, at practically zero marginal cost, without the need to have some kind of investment in distribution and in media such as CDs to distribute them on.

And the music industry in the beginning was very reluctant to really look at this as an opportunity, as a way of basically selling music at a cheaper overhead. Instead, they were quite skeptical of this new World and weren’t really doing much with it. And this lack of innovation in this area was picked up by teenagers especially, who were using illegal ways to distribute culture and especially music online. And we’re challenging the existing laws and norms around copyright. And some of you may have been among these teenagers. Others may think, “Well I don’t really have a lot of sympathy for that,” or maybe thinking back at your own behavior, “That wasn’t really political. I just wanted to listen to music.”

And that is fair enough. I think that may be true for a lot of people. But at the same time I think in order to understand why the Pirate Party came about as a political party, you have to look at the way that these file sharers—often minors—were being addressed by the political establishment and by the cultural lobbyists in particular. And what kinds of measures were being lobbied for by the cultural industries, especially the surveillance of people’s online behavior, which we’ve only learned probably years later was going to become a much broader problem for a fundamental rights. And even things like three strikes laws like an entire family could lose their Internet connection if some illegal downloads had taken place over that connection.

And I want to illustrate this by showing you a short clip from a commercial that was being shown in Germany both in cinemas and also on DVDs by the film industry. So this was a campaign that was aimed at paying customers, people who were actually paying to go to the movies. And I think it is illustrating the tone of the debate that was going on. And I apologize, it’s in German. [Plays excerpt of the following video from ~0:19–0:35]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jddc3S7Oy30

What you can see here is that not only was the film industry basically perpetuating rape culture, the message of this clip is that if you start file sharing you will go to prison. And in prison you may very well be raped. And this rape is part of your punishment. The slogan of this campaign is “harsh but fair.” So the stated goal of this campaign was to equate copyright infringement—to take it out of the area of kind of minor infractions such as getting a parking ticket, and to equate it with violent crime. And the the word that is used “raubkopierah” is basically the German version of “pirate.” It has slightly different connotations because raubkopierah literally means not only are you a criminal who is stealing from somebody else, you are using violence to do so. So it was a very harsh attack on file sharers and it was used to justify some egregious surveillance measures that were put in place and that people started getting upset about.

And perhaps not very surprisingly, some people started appropriating this term “pirate” that was used to describe them. And the music and film industries probably didn’t think about this very deeply, that actually if you use the label pirate to describe somebody, that pirates are actually considered quite cool by a lot of people. They even later did Pirates of the Caribbean and stuff like that.

So the best example probably of this appropriation of the term pirate by the pirates themselves is The Pirate Bay, that even used this iconic ship as their logo. And The Pirate Bay started out in Sweden, and it’s a file sharing site that is still around today The people who founded it had quite a lot of connections to the academic scenes and the arts scenes in Sweden. And even though it was really vilified by the music industry, I think it’s important to know also that a lot of smaller, independent bands were actually using The Pirate Bay actively to get the word out.

But it was clearly a kind of direct action, where people were doing something that was illegal in order to spread information and culture in a new way. And the Pirate Party somewhat split off from this treatment. It also was founded in Sweden, kind of coming out of more less the same cultural background. But they were saying actually it’s not about breaking the laws that exist today but rather trying to go into the institutions and change the copyright law into a form that actually works with the Internet instead of against it.

And the Pirate Party that was founded in 2006 in Sweden actually started gaining popularity quite quickly. It was because people started realizing that the appeal of the pirates was going beyond just rebelling against the powers that be, but actually people were seeing that for the first time there was a party that was taking the digital revolution seriously as a political issue, that were looking at the Internet not primarily as a threat but as an opportunity for empowering more people to participate in democracy. And who were also realizing that this promise of participation would not just come about naturally through technological progress but would be something that you actually have to fight for in order to make sure that the Internet and technology does not just get turned into a tool for the powerful, for surveillance, and for commercialization.

So the Pirate Party supporters pretty quickly were made up out of civil liberties advocates, out of people who were interested direct democracy and using the Internet as a tool for getting more people active in politics. And also a lot of academics, librarians, people who were coming into conflict with copyright law in their daily lives basically through no fault of their own.

And myself at this time in 2009, when the Swedish Pirate Party had its first electoral success—they were actually elected into the European Parliament in 2009—I was still a member of a very boring, old, established party. I was a member of the German Social Democrats, which is basically the equivalent of the Democratic Party in the US. It’s around for 150 years. And I left the Social Democratic Party when the leadership of the party decided to back a government bill that would introduce secret governments blacklists of web sites that would be filtered. And there was quite a lot of opposition within the party from younger members saying that this is a terrible idea. And they were basically not listened to and left the party in great numbers. And quite a lot of them then ended up joining the Pirate Party, which was fighting against this law.

I started becoming quite active in the Pirate Party over the next years, and mostly I was organizing protests against the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, ACTA. This is an international treaty—or was going to be an international treaty—that was going to be negotiated between the EU, the United States, and quite a number of other countries, and that would have drastically increased the powers of border agencies and other law enforcement to crack down on copyright infringement and other IP infringement.

And at this time in 2012, there were other people in the United States such as Aaron Swartz who were organizing protests against SOPA and PIPA, which were national laws that going to do something quite similar. And these successful protests in the US, they kind of spilled over into the EU, and all of a sudden there were tens of thousands of people on the streets, mostly young people.

And the Pirate Party, being in the European Parliament with just two members had the opportunity to basically explain to their colleagues what the hell was going. Why were there all of a sudden these protests on this completely arcane topic that they hadn’t really thought about. And in the end the European Parliament actually ended up rejecting the Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement and it was the first time, or one of the first times, that the European Parliament was using its newly gained power to actually reject a trade agreement. And even to this day some of the EU politicians and bureaucrats in Brussels are pointing at ACTA as an example of what happens if politicians are ignoring what the people think.

So, I was quite inspired by what happened with ACTA because on the one hand I could see that our actions of organizing protests were actually having an effect. And that just having a very small number of people in the European Parliament could actually bring about change. That this was the place where digital policy was being made in Europe. And so I was inspired to run for the European Parliament in 2014. And well, as you know today I actually managed to get myself elected. And this was actually not as difficult as one might think, because well, we have a very neat thing. The electoral system for the European elections is proportional representation. It’s a system where the number of votes you get is proportional to the number of seats you get. And that’s a very intricate system that has a number of very interesting features. For example, the party that gets the most votes actually wins—you should try that sometime. It also means that about 1% of the voters in Germany can send one member to the European Parliament. And that’s how I got elected.

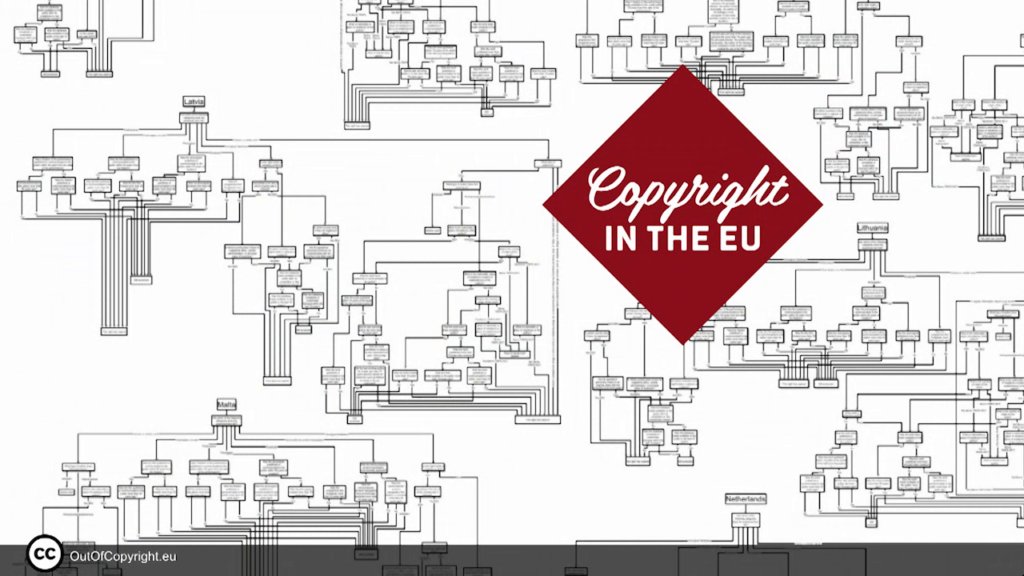

And being the only pirate in the European Parliament from 2014 on, it was quite clear that I would focus my activities on the reform of copyright. And in order to understand just how broken the European copyright system is, even in comparison to the US, I want you to have a look at this diagram. It’s just a very short cutout of a larger poster that shows all the questions you have to answer in order to find out whether a particular work of art is in copyright or out of copyright in the EU.

Each one of these little decision trees represents one country, and there are twenty-eight of them in the European Union. And I think it illustrates that there is no such thing as a European copyright law. This is an area that is still governed by national law to the largest extent, and all the EU has done so far is to introduce some minimum standards for the protection of rightsholders. But there are no minimum standards for the protection of the public interest.

On the contrary, the US put in place some rules on what member states are not allowed to protect [in] the public interest. So for example, a member state of the EU would not be allowed to put in place something like Fair Use. And I think the Fair Use system in the US is very interesting because it is actually built on norms that already exist in society and that people understand kind of intuitively.

So for example there’s this norm that you shouldn’t use a work in a way that diminishes its value in the eyes of the author. So for example if you’re making a TV commercial for a car or whatever and you want to use a piece of political art, you should very well ask the author before you do that and you should probably pay them for it as well. But if you are creating some artwork of your own and you’re doing this not for commercial purposes but more for your own amusement or education, and you’re using all kinds of little pieces of different people’s art and creating something new out of it, you’re probably going to be fine without asking for permission. And I think that’s a very eminently sensible approach to copyright.

In the EU this is not possible. Instead the member states have to pick and choose from a closed list of very narrowly-defined copyright exceptions for purposes such as quotation or parody, and these exceptions are differently defined in the different member states. So that means even if you follow the copyright law if your own country to the T, the moment you put something online, you can still get sued by somebody who has seen this artwork from different European country, because of course on the Internet you don’t have these national borders. So this is why I was working on copyright from the very start.

And I have three main goals in this copyright reform that I’m still working on to this day. And the first one is to legalize the kind of everyday culture that the Internet has facilitated, such as remix, mashups, lip dubs, all this kind of stuff that is generally already legal in the United States under Fair Use.

Secondly, I want to increase access to knowledge and information by making sure that our public institutions such as libraries, archives, museums, and universities actually have a copyright system that allows them to do their job, which is not the case today.

And finally, I think that the copyright law needs to be regulated at the appropriate level. So in that European case it doesn’t make sense to have these twenty-eight different laws for something that so fundamentally affects the incident.

So there I was, one out of 751 members of the European Parliament. So it was quite obvious that even though I had all these goals about copyright reform, simply voting for them would not really change very much. And I also realized that while the term “pirate” was very useful to the outside to get attention, probably it would create some, well…misconceptions or prejudice from other members that I would have to overcome.

So I tried to think about what I could do to make sure that I wouldn’t be seen as too radical. And so I decided so to buy a suit. Very important life change for me. And I also joined one of the broader political groups in the European Parliament, the Greens/EFA group. And I came up with a strategy of how I could act within the European Parliament to actually have an impact.

And I’ve mostly done this in two different ways, two different strategies. On the one hand, I take the role of the policy wonk. One of the great advantages of coming from such an issue-specific party as the Pirate Party is that I am allowed to devote more or less my entire time to working on copyright reform and none of my voters are going to get upset if I do that and don’t comment on Brexit or Trump. Although, I do.

But this basically meant that I could become the most knowledgeable and the most vocal, outspoken member on copyright issues. And even my greatest enemies in this debate would have to somehow engage with me and would have to admit that I knew what I was talking about.

To the outside world, I was taking quite a different role. I was acting less like a public representative and more like a campaigner. So almost like a journalist, I was telling the public what was happening on copyright reform. Because it’s such a specialized topic and the EU lawmaking process does not get that much media attention that people wouldn’t necessarily even know what was being discussed. So my goal and my job to a large extent is to translate what is happening in the European Parliament into a language that regular people can understand.

And I think beyond just this outside communication, one really important advantage of being on the inside of such an institution is not the one vote out of 750 that you get, but rather the seat at the table. So in the case of the European Parliament, the way that the legislative process works is you get the proposal for a new bill and then each of the eight political groups in the European Parliament appoints one negotiator on behalf of their group. And these negotiators try to form a compromise, ideally, or if they can’t reach a consensus they will go for the broadest majority possible. So being one of those eight people actually gives you quite an outsized influence over what is going on. And so I made sure that for my political group I would be the negotiator on all things copyright.

And all of this probably doesn’t sound all that rebellious at all. It’s pretty standard policymaking, I suppose. And it’s true that I don’t end up breaking the law very much in my job anymore. Instead there are a lot of unwritten rules in politics that I come into conflict with. And on the contrary, when it comes to written rules what I found is that there are actually very powerful actors and very powerful institutions that break the law all the time.

The council, for example, which is the second legislative chamber of the EU that is made up of national governments, they are super intransparent. There aren’t transparency laws, but for example they just completely ignore the freedom of information laws that cover them and just pretend like don’t they apply to them. And well, I guess that’s because it’s never called disobedience if it’s the powerful doing it. And the role that I take as a kind of opposition within this system is much more holding this entire system and the more powerful players within it accountable. I do this on the one hand not by stepping outside of the laws but by using the laws in a creative way. So especially things like freedom of information can get extremely annoying to people. And what I also do is to try to bring attention and make it public if rules are actually being broken by the powerful. And in this way, I believe that holding the powerful accountable within such an institution can actually be an act of defiance in and of itself.

I want to give you a few examples of what kinds of conventions or unwritten rules I might have broken or changed. The European Commission is the executive body of the EU, and it’s made up of commissioners. And these commissioners actually hold a lot of political power. They draft the laws for the EU. However, they are pretty much unknown to the European public, and that’s quite a remarkable. They are elected by the European Parliament but generally they don’t really contribute to being known to the outside world. Like they don’t really campaign for their election, they show up to a hearing in a European Parliament committee and that’s more or less all that happens before their election.

Following the great suggestion by @Senficon, I will do a Twitter chat using the hashtag #AskAnsip from 11–12 am on Oct 15.

— Andrus Ansip (@Ansip_EU) October 10, 2014

So I managed to convince one of the commissioners not just to answer questions from the European Parliament but also to answer questions from the public before his election was coming up. And you probably still don’t know who Andrus Ansip is, but at least we’re working on changing that.

Another thing, an area where there actually are very clear rules, is that in the European Parliament when we are voting on legislation, all the amendments to this legislation that we vote on are public. And that’s a very sensible rule. But there is an exception to this rule, which is that the different negotiators can come up with compromises at the last minute that will be voted instead of those amendments. And that in and of itself is not really a problem; it’s quite it’s sensible.

But the problem is that there is no process in place to actually make those compromise amendments public. So that means the MEPs maybe send these these texts that are actually going to be the new laws to their favorite lobbyists. But to a large extent the public does not actually know what we vote on until the vote’s already over. So I started publishing some of those compromise amendments on copyright law, and I found that some of my colleagues were very upset about this and called it “leaking,” which I some kind of funny because it’s basically the legislative text that we were about to vote on the next day.

I also started publishing my lobby meetings. I had a tool built that automates this process and just puts all lobby meetings into a public calendar. And this tool was actually— Well, some of my colleagues started using it, others are making fun of it. But the lobbyists themselves, they don’t always like it very much and say they have data protection concerns about it. But they all look at it to see who else is lobbying.

So, one time I was given an award. This is kind of a weird award. So, the MEP Awards are sponsored by different lobby groups to honor the achievements of particular MEPs. So for example you have like, I don’t know, the Brewers Association of Europe sponsoring the healthcare award. And I don’t know, the environmental award is sponsored by Plastics Europe, and the development policy award is sponsored by Fertilizers Europe, that sort of thing. And so I was giving this award for digital policy and I used my speech to draw attention to some of the lobbying practices that were going on:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=udt2D13YVMA

One of perhaps the most important ways that I’ve broken some conventions is the convention that political decisions or divisions are among party lines. And what I found is that copyright policy is not a partisan issue at all. The conflict lines, they go much more along age groups, along geography in certain cases. But you can find the most progressive and the most conservative positions within the same party.

So what I’ve done is to speak to a lot of individual members of parliament, sometimes bypassing the official negotiator, sometimes they were the official negotiators, and to build a broad alliance against a new proposal to extend extra copyrights to very short parts of newspaper articles. [Plays excerpt of the following video from 0:45 (1:31 total; captioned)]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TKf4Mkp93‑c

So, it’s not clear yet if this initiative is going to be successful. The commission didn’t listen to us, put forward a proposal to basically make it illegal to copy the headline of a newspaper article without permission from the publisher. And the European Parliament will vote on that in October, and we’re not sure yet how this is going to go. But organizations such as Open Media in Canada, for example, are quite active in this campaign to save the link and to try to make sure that the dissemination of knowledge over the Internet such as by using hyperlinks can continue and is not encumbered by copyright.

I’ve done quite similar campaigns around the issue of geoblocking, for example. So geoblocking is basically when you see the message “This video is not available in your country.” It’s probably not such a big problem in the United States because it’s quite a large country. But in the EU, you have all these tiny countries next to each other, often speaking the same language. And then you have a lot of content that is really blocked based on your IP address. And what I did was I tried to find some of the NGOs that represent the groups that are most affected by this but are not necessarily active in digital policy and get them together.

Does this stuff work in practice? Well, not always. One of my biggest successes where it did work was that I passed the most progressive report on copyright law by the European Parliament, that I drafted myself. And this report… Well, it ruffled quite a lot of feathers. So it inspired, for example, a French publisher to actually print a book and give it away in bookstores for free, called “Free is stealing” and saying that this report was about to bring about the end of copyright. And of course not without making a lot of disparaging remarks about my age and my gender.

I managed to mobilize together with Wikimedia half a million people to save a quite obscure exception to copyright called “Freedom of panorama” that allows you to take pictures of public places without having to first ask permission from the architect. And this inspired Wired to write this very nice headline, but I hope you don’t blame me for all the selfies because of this.

Another project that I started is that the EU is now investing millions of euros in the security of open source software. This is a pilot project that is financing audits of software that is used within the institutions, and if everything goes well this is going to become a permanent item in the budget of the EU.

And finally, when the EU was discussing the extension of trade secrets protection, I was not able to stop this but I was able to help strengthen the provision that would protect whistleblowers when they disclose trade secrets.

Why I’m working on all these quite different topics like copyright reform, whistleblower protection, free software… What they all have in common is that they are about access to knowledge. And I think looking at the theme of this conference, access to knowledge and the freedom to speak out is really essential for defiance, and it’s very important for politics as well. Because the most important thing that I have learned in the Parliament is that it’s not us politicians who actually bring about change. We are always a bit behind the times. You can have the most radical ideas as a politician, but you’re not going to get them passed unless you convince a majority of your peers. And that’s only going to happen if somebody has planted the seed for a change in thinking in the society.

And this is what defiant people actually do. So you have people like Aaron Swartz or Alexandra Elbakyan who have been challenging the academic publishing system that is actually quite unfair to academics themselves, who are supposed to be the beneficiaries of copyright in this area. You have people like Chelsea Manning, who has disclosed information believing that it was the right thing to do.

The guy in the middle, Antoine Deltour, is the whistleblower behind the LuxLeaks tax scandal in Europe. He exposed some information about how companies were paying or not paying taxes. And after this disclosure the European Commission actually recovered tens of millions of euros from companies such as Starbucks and Fiat, and declared their tax practices illegal under EU law. And it passed a bunch of new transparency laws and closed some tax loopholes. But at the same time that didn’t stop the Luxembourgish courts to slap Mr. Deltour with a a suspended prison sentence for disclosing trade secrets.

So this shows kind of the cognitive dissonance that we have sometimes with dealing with defiant people. We absolutely need them to bring about change, but we are still willing to sacrifice them, and they are making great sacrifices for bringing about this change.

This is also true for Edward Snowden, I believe. When we were discussing a European data protection regulation, it looked for a long time that basically the companies that wanted to do everything with their data and the governments that wanted to survey us were going to win this fight. But when Edward Snowden made his revelations, the discourse on privacy changed completely in Europe and it was probably the most important single thing that made us change direction and we actually ended up with quite a robust data protection law.

So, all these people I think are making great sacrifices for questioning the morality of some of the existing laws, and they are the seed that actually makes it possible for us to change the laws and to reflect on whether what we have is right. And I think that is necessary for any kind of societal progress.

So as myself sitting in the European Parliament while having a seat at the table is great and of course I would be happy to have more pirates there. But what is actually most important to be able to achieve anything is that there are people out there who are actually willing to question the laws that we have today and sometimes to break them. And we’re here to celebrate exactly those people, those stories. And I am extremely happy and honored to be able to be part of that. Thank you very much.

Farai Chideya: Thank you Julia. Now you can see why this movement of pirates is so powerful. And we’re going to move on to talking about unlikely alliances in questions of defiance and governance. This is “The Heat Enlisting the Street.” We’ve got Ed You, who’s a supervisory special agent in the FBI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction directorate in the Biological Countermeasures Unit, and he works closely with underground biohackers to expand the FBI’s outreach and work together.