Ed You: So, good morning. Before I start I want to say a big thank you the Media Lab and Joi for the invitation. I consider it a privilege to be able speak to you all. And I’m just going to go ahead and launch right into it because it’s probably going to be something you haven’t quite expected from the FBI. But let me set the tone by saying it’s not only in keeping with today’s theme of defiance, but I’m going to even go so far as saying that you’re going to see some outright aberrations and what that translates into.

So when you saw the agenda and you saw the FBI, maybe this sort of came to mind. Of course, right? And you saw me coming onto the stage so I’m sorry if I disappointed. But Hollywood built its reputation on our agency because if you think about it, we are a law enforcement agency and we are very good at what we do when it comes to investigations. But in today’s world, if you think about where things are going, investigations doesn’t work anymore in the fact that it’s inherently reactive. Meaning that something happens, we go in after the fact and, we do our investigations, collect our evidence, find the perpetrator.

Well, unfortunately September 11, 2001, 9⁄11, was a huge wake up call for the entire US and the FBI in particular. And in light of this reputation and our legacy, because we are over one hundred years old, we had to defy our own heritage. And if you look at our number one priority now, it’s one of prevention. How do you stop something like 9⁄11 from ever happening again?

And I’m a product of that defiance even within the organization. Because my background—and there’s a reason why I think I’m actually better than these guys—is that my background’s— I’m a biochemist and molecular biologist by training. And I think pre 9⁄11, the FBI probably would not have hired someone like me. But in this world where that number one priority is to protect our country and all of you, our hiring practices have diversified over time.

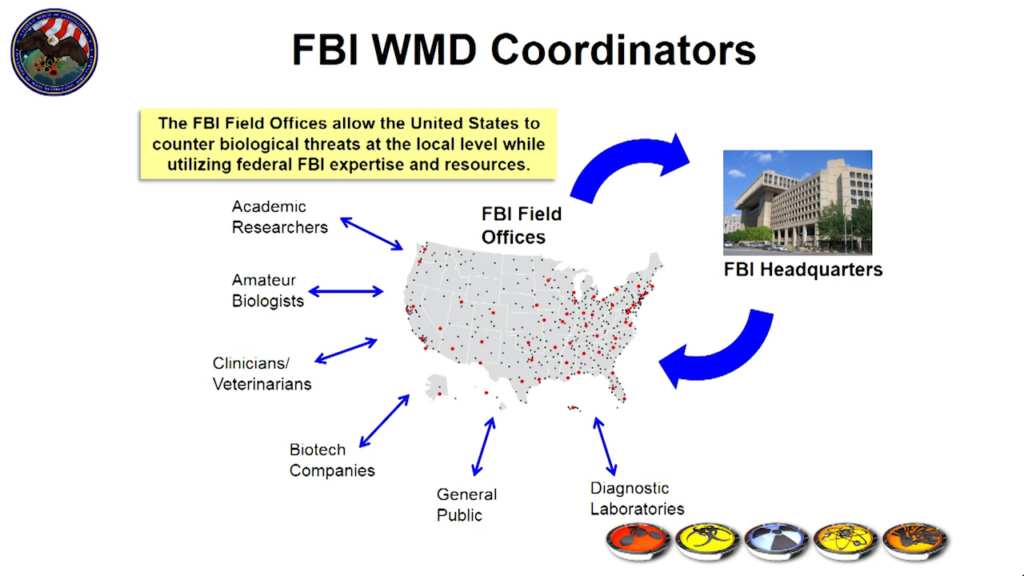

But I have to give a hats off, and this is a shameless plug, but one of the key components of our being able to be different is this important position within the FBI, the WMD Coordinator. These are special agents, men and women that are trained in chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear matters. They are your local ambassador. And there’s at least one station in each of our fifty-six field offices across the US. I’m very pleased to introduce Special Agent Josh Canter. He is the Assistant WMD Coordinator here right in the Boston field office. And again, if you’re in the area please say hello to him because they are the ones that reach out and provide connections to state and local law enforcement, to public health. They proactively, before anything happens, reached out to hospitals, companies, universities, other institutions within their jurisdiction, to establish those important partnerships before something happens. Or in the case that something does happen, now you know somebody within the FBI that understands where you’re coming from and that can adequately assess what the issues are and provide assistance.

So before I actually talk a little bit about what defiance looks like from our program’s standpoint, I want to set the stage for you where we’re looking right now. Because the 21st century is going to be the century of life sciences, where in the prior century it was all about the Internet, the information age, and personal computing. This century’s all going to be about what the impact is going to be of bio in our lives. And that holds huge amounts of promise, but it also poses some interesting security questions for us.

Deadly H5N1 bird flu needs just 5 mutations to spread easily in people, LA Times, April 15, 2014

So, just a few years ago there were a few publications that came out on how two research groups, one in the Netherlands and one here in the US, modified bird flu and made it transmissible amongst mammals. So ostensibly it could potentially be— You know, usually it’s a one-off where you get exposed to the bird flu, an individual gets infected, it impacts them, it doesn’t get passed on to another human. Well this group made the modifications where it could get past amongst ferret to ferret to ferret, and ostensibly it could be amongst humans.

This caused a huge issue because now the stories flew that oh my gosh, this is 28 Days Later, this is the zombie apocalypse. You’re going to now produce the next pandemic. And there was a lot of policy discussions about the potential consequences of this. So it’s a biosecurity issue.

Moratorium on Gain-of-Function Research; The Scientist, October 21, 2014

And as a result of this there was actually a complete moratorium on this line of research, globally. Think about that for a second. The entire international scientific community pushed pause on research in this area. Because they didn’t want to do a reassessment on looking at the safety and security implications. That doesn’t happen very often. But it just shows you they took it upon themselves to look at what the implications were.

But here’s the dark side of what potentially could happen. This is a snapshot from a blog. And look at the text here. It says “mad scientists create bird flu genetically-modified bioterrorism virus.” So one thing’s for sure, the US government is not in the business of doing bioterrorism research. It characterizes scientists as being mad. And the only saving grace is that at least in the picture it’s a CIA patch and not the FBI patch. So I’m kind of grateful for that. Small favors.

But the point here is how we communicate how science is being done and why. Yes it’s a blog. But this is an indication of the general public. And where does science get its resources, the funding to do the work like in places like MIT? It’s taxpayer money. This is the general public. This is where the funding for research comes from. So if we don’t get the message right, this could be the blowback. So one of the consequences for security that we oftentimes don’t really think about.

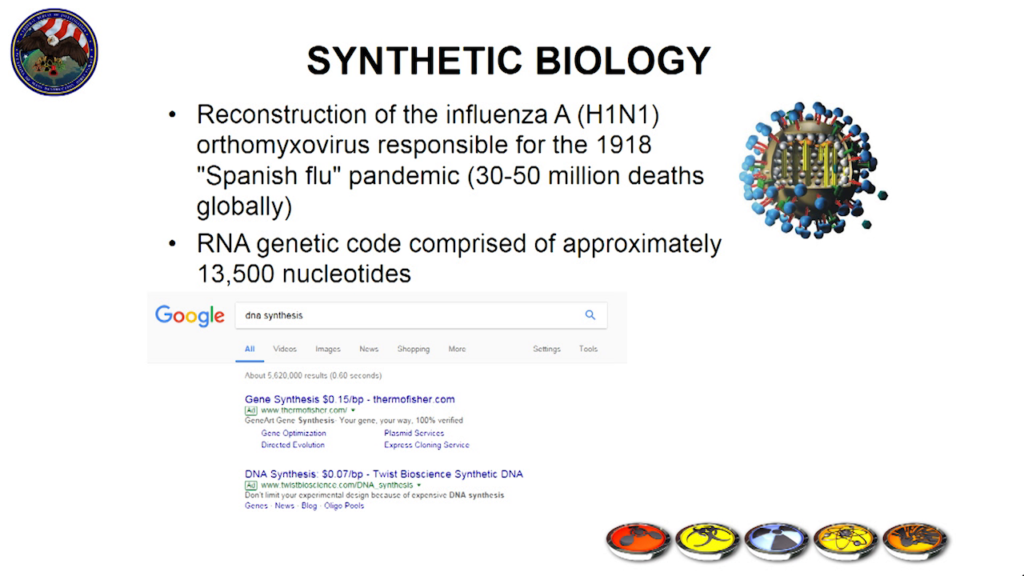

And here’s another snapshot of where biotech is taking us today, too. So, synthetic biology. We are able to manufacture DNA very very efficiently. And just as a case study, look at the 1918 influenza virus. This is “Spanish flu” went around the world twice, responsible for thirty to fifty million fatalities. It’s only 13,500 nucleotides long. So 13,500 of those As, Cs, Gs, and Ts of the DNA sequence. Theoretically, you can email that small text file to a DNA company that advertises they synthesize DNA at seven cents per base. You could get the 1918 influenza virus for the bargain basement price and $945.

Revealed: the lax laws that could allow assembly of deadly virus DNA, The Guardian, 2006

So I say theoretically because well…you know, some issues for trying to do that. And how that happened is that something like that actually happened a few years back. A reporter for The Guardian sent with a Yahoo! email account a personal credit card and an apartment address, a DNA order emailed to a company and within a month got his order in the mail. And inside the plastic vial was the DNA for smallpox. Really bad. And his resulting story was, “Wow. The laws don’t exist to prevent a bad guy from ordering smallpox or ebola and getting it in the mail.”

And the blowback here was it was a firestorm of security discussions on the policy. Companies, the whole entire private sector did a gut check. And then today, if you submit an order, the order is screened and the customer is screened. So the companies know what they’re making and who they’re selling it to. So this was a little bit of a close call.

Slide from slide deck at DIYbio

And something that’s really cool and a whole creative form of defiance is the dawn of the age of DIY bio, the amateur biohacker. So these are individuals, not only in the US but internationally now, that firmly believe it this is the century of the life sciences, the next Bill Gates, the next Steve Jobs, is going to come out of bio. I firmly believe that too.

But they also believe that it’s not fair that only companies and universities or the governments can actually do original research. So they took it upon themselves to— Let’s break into this field. Let’s democratize science. And so ranging from PhDs all the way to artists and musicians and architects are getting involved in biological research.

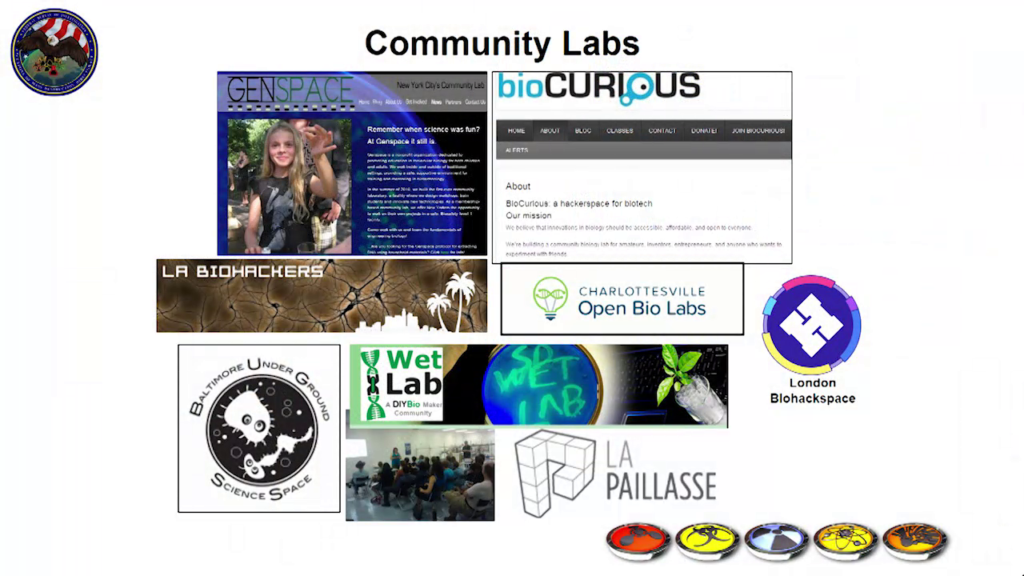

And you see the evolution of things like not only garage labs but community labs where like-minded individuals come together and pool their resources, buy used equipment, go for their own pet projects. And it really is if you think about it, a defiance in the academic models of being able to conduct research is set up.

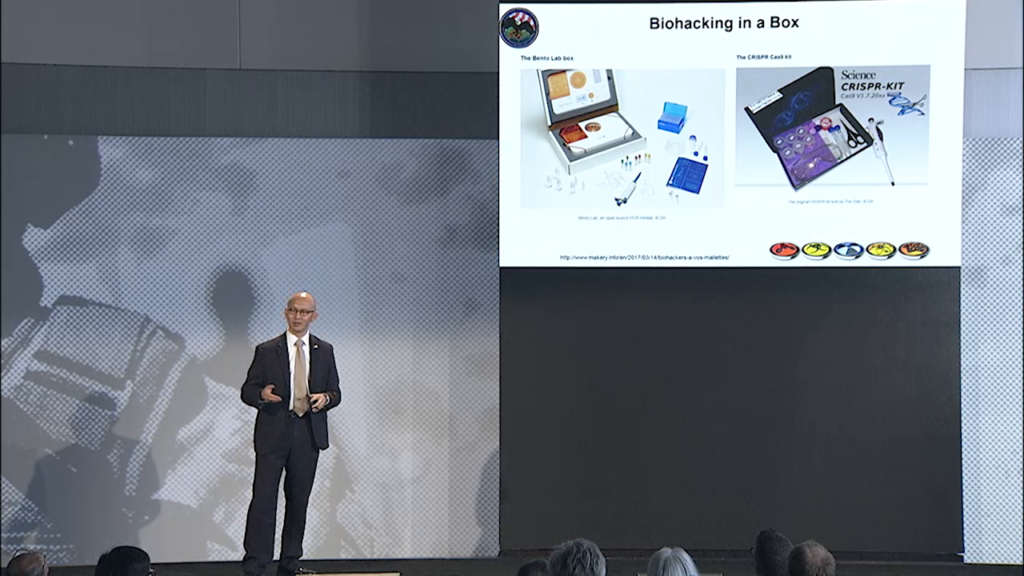

Biohackers, open your boxes!, Makery, March 14, 2017

And that has also evolved into some really cool innovation. So things like having an actual laboratory in a box that’s the size of a Japanese bento lunch box. One of the ones that are more interesting is the one on the far right. You can get your own home genome editing kit. So for those of you familiar, CRISPR/Cas9 is a big big issue in the news right now. But now you actually have a kit that you can do your own gene editing at home. Very very cool.

The point is is that this is a community where it’s a genuine engine of innovation. So if you think about the personal computing age, it all started with the Homebrew Computer Club, and that all started in their own garages as well, too.

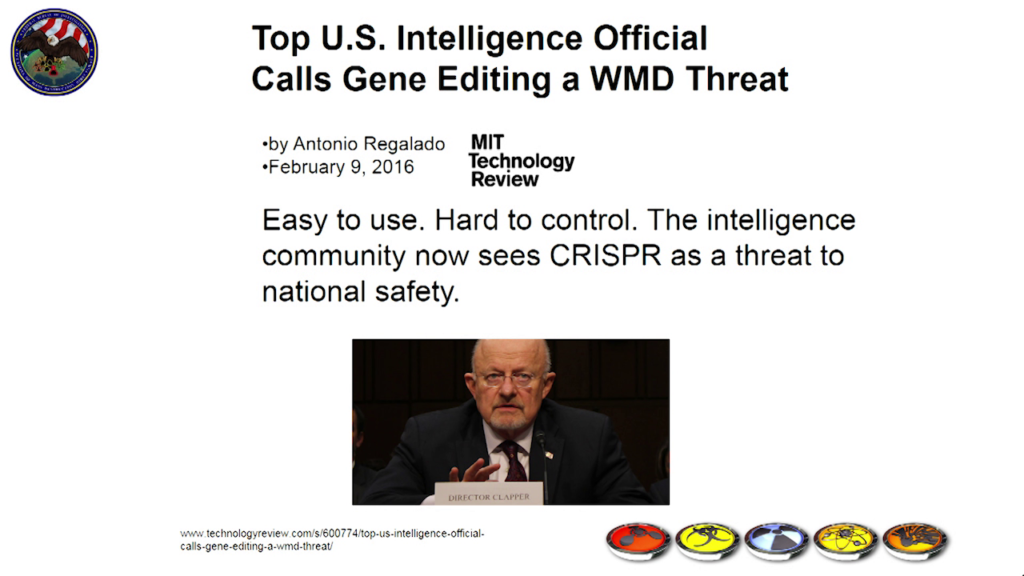

Top U.S. Intelligence Official Calls Gene Editing a WMD Threat, MIT Technology Review, February 9, 2016

But then you have things like this in the background, where the former director of the national intelligence committee said that gene editing? It’s the equivalent of a weapon of mass destruction. So in the same list where you talk about North Korea and their nuclear program, Iran and their nuclear program, and then gene editing. Well, unfortunately that stone was set and some of the consequences, though, is this: that you actually have countries targeting the biohackers, the amateur community. That in light of well, unless you have the proper authorizations and the permits and the licensing, they can drop the hammer on you. Even if it’s going to be legitimate, innovative research.

But what’s the dark side of that, potentially? Well, you might have this:

If it becomes so burdensome on the community, you’ll drive it underground. And in the grand scheme of things, do you want this to be the level of discourse between governments and other entities with the amateur community? Absolutely not. If anything this is going to cause more problems than solving any.

So, what I’m trying articulate here is that there is a really fine balance between how do you spur and invigorate innovation, and then also address security at the same time. Because one cannot drown out the other. Because you’re going to have all kinds of issues.

Say for example you do drop the bomb on the regulations and make it so hard to do research, all in the name of security? That is a whole other security risk. Now you’re going to be hindering innovation. You’re going to be blocking developments of new health tools, new treatments, new vaccines.

So you can’t have that, either. So there is a sweet spot where you are able to support both. And that’s where we come into the picture. Like I said, the FBI’s history and legacy was all about the reactive “let’s go get the bad guy.” Now it’s about how do we protect everyone? How do we protect this important innovation? And if you really think about that, that is so outside the norm. That is not your typical law enforcement perspective. And that’s why we’ve heavily been engaged in “let’s go out and reach out to the communities.”

Because if you really want to be able to protect the things like biology, which is inherently open, which is inherently shared, that’s its strength? Putting up walls is not the answer. One of the best ways is let’s [go] and join up with the community together. And safeguarding science.

And this is actually the message that we use when we go out and talk to the biohackers and the students of the world. It’s three very simple tenets, which we “deputize.” One, be passionate about what you do. You’re not going to succeed in life unless you find something that you can really glom onto, really are willing to put in your blood, sweat, and tears into, and that’s how you’re really going to succeed.

And then also be guardians of science. It’s not just protecting the integrity of science, but make sure it doesn’t get abused, exploited, or misused.

And then third and probably most importantly, pass it on. How do you now become a mentor to those who come after you, to pass on these tenets? That’s the message. It’s not thou shalt not, it is how do we together protect this important enterprise?

And one example of this is that we became sponsors of something called iGEM, the International Genetically Engineered Machine competition. This is an international synthetic biology competition targeting undergraduates and high schoolers. This started in 2004 with just five US-based universities and sixty students altogether. Over time it has now grown—I think last competition had over 7,000 participants from over 140 universities and from more than 40 countries.

And my program has become a sponsor of iGEM in 2009. And that raised a lot of eyebrows initially when I tried to push this through. “Why do you want to support a science fair?” But the point is that if you look here, this is the cutting edge of biology. This is actually the genesis of the amateur biohacker community. Because they got a taste of how powerful biology is, what the promise can be. And how can they do more outside of even a competition? Outside of companies. Outside of universities.

And here’s a really cool example that not only has this competition over the years engaged in looking at the merits of the projects, but they look at the safety. And they also look at the security implications. And it hasn’t just been you know, here’s the FBI talking about protecting science. But you actually see some really cool action.

Security page, iGEM wiki

And this is a team from China. This iGEM team, they had their scientific project. But then they realized “let’s do something regarding security.” And they they tackled this project. They identified seventeen Chinese medical companies that had potentially very dangerous, hazardous products. And again using just a personal credit card, a residential address, they submitted these orders to all seventeen companies. And to their dismay they found that sixteen out of the seventeen companies were going to say, “Okay, we’re going to ship it to you.”

The students immediately canceled the orders and they drafted a white paper, a letter, criticizing the Chinese government for not doing more to protect the public, to protect science, and sent it to the relevant Chinese agencies. What a fantastic act of defiance that is. That not only did they do their science project, but they actually took the extra step.

And rest assured, they didn’t disappear. They actually did become mentors of their own iGEM teams. But don’t look at just the act. Think about this for a second. Look at that picture of those young faces. That’s the next generation of future scientists. Maybe future owners of their own companies. Or even ideally, maybe they’re going to be there the policy members that we might be sitting across the table from in negotiations when we’re in diplomacy. And yet they had this little bit of a nugget of what it means to, in this act of defiance, become group true citizens of science and be able to protect it. Even from their own government. So, very profound. But it’s just a little bit of engagement of the FBI just going a little bit beyond its comfort level. But this is one of the results that you can get.

We also engage the biohacker community. We have regular meetups. And we provide a meeting space. We bring in representatives from the hacker community. And those all-important WMD coordinators, your local representative, making sure that they know who their local FBI representative is. And this has been wildly successful. Here’s a quote from one of the founders of one of those community labs I mentioned. They say, “We reached out to our local WMD Coordinator, invited them to our grand opening. And the FBI wishes us well because they know the more educated the public is,” you know, they have a hacker community, “about what could constitute a biological threat, the easier its job is going to be.”

We reached out to our local weapons of mass destruction coordinator. We are very friendly with our local FBI representative. He has come to our workshops and he came to our opening.

The FBI wishes us well because they know the more educated the public is about what would constitute a biological threat, the easier its job is going to be.

Dr. Ellen Jorgensen, Genspace, Dawn of the BioHackers, Discover Magazine, October 2011 [presentation slide]

This is wonderful because it’s not FBI, it’s not Ed You saying it, it’s a member of the hacker community. And again, read into this for a second. This is a community that is very anti-establishment. They don’t want to be bounded by anything. And yet, under the context of safeguarding science, they’re willing to work and want to work with the epitome of the G. And that is really something pretty powerful.

Invite a FBI agent to participate in your Building with Biology event!, Building with Biology, July 6, 2016

Also, you have things like this. Hey! Invite your local FBI agent to your local biohacker event. And by the way that picture up there, that was in Boston and that was Josh Canter in that picture. But again, how different is that in that if the members of the communities welcome us with open arms and wanting us to be there to talk about what does it mean to become a guardian of science.

As the field progresses, the government should continue to assess specific security and safety risks of synthetic biology research activities in both institutional and non-institutional settings (DIYbio).

From cutting-edge academic institutes, to industrial research centers, to private laboratories in basements and garages, progress is increasingly driven by innovation and open access to insights and materials needed to advance individual initiatives.

[from presentation slide]

And here’s where it gets very very interesting. That over the years, again through these small but significant successes, whether it’s through universities, companies, with students, with biohackers, the world’s starting to take notice. That here up top you had President Obama charge a commission to look at biotechnology and synthetic biology and where it’s going. And this commission actually highlighted the FBI’s best practice of reaching out to the community and buildings those all-important bridges. We actually have a presidential national strategy to countering biological threats, and it says that hey, DIY bio? It’s a good thing. We need more of that. We need to protect it. And then you even have a report coming out of the United Nations saying this type of proactive outreach by a national law enforcement agency? That needs to be emulated.

And a little bit of an anecdote. One of the meetups that we had between ourselves and the DIY bio community, there was one representative from an international lab. Was so gung-ho about wanting to do something similar when they went back to their home country. They went to their national police headquarters, knocked on the door and said, “Hey! I’m a DIY bio-er. And the response was, ‘Who the heck are you and what the hell are you doing?’ ” So it just shows you that yeah, we’re doing right, we’re making progress here. But it can’t just be here. Bio is—again, it’s international, it’s global, it knows no boundaries. But if we want to protect and make sure that it doesn’t get abused, the same kind of engagement and education and partnership building has to happen elsewhere as well, too.

And at the end of the day, it’s not just about the protecting of biology or the guardianship, but it’s really this kind of impactfulness. That this is the level of engagement that we’re getting. That this up and coming generation are going to be the ones that are going to have their own acts of defiance. That if they’re willing to go beyond the norms of what their typical lives are going to be in academia. That they want to take that extra step. If you’re a hacker and you’re building your own gene editing kit, then yeah let’s go ahead and work with the FBI. Let’s go ahead and invite them out to dinner and have a conversation.

The beauty of this, too, is that this is a little bit of a pushing the comfort level. It not only gets the message out, but as I just showcased, members of the hacker community can actually come up with solutions on behalf of the FBI. And ideally, too, that… We’ve done this long enough that there are actually some of these individuals that are applying to the FBI. What a fantastic act of defiance that is, that— [audience laughter] Right? You’re going to be a hacker? You’re going to be a bioengineer or biochemist? I’m a good example here, right. I’m a prime, second-generation Asian American, and parents were hoping for an engineer or a physician. Ended up being a special agent. Sorry, mom and dad.

But how awesome is that if you have members of this community joining organizations like the FBI? Going into government. Going into policy. Having their voices heard. They never would have considered that before. It would have been one of those traditional tracks. But this can potentially be incredibly powerful, incredibly motivating. So it’s not just the FBI that are part the conversations at the local level, but also at the governmental level. And I would love for a future where you have one of those biohackers take my place. Have a seat at the table. Have a seat at the UN. And have that conversation.

So it really is going to be important that there are different levels of defiance. I consider myself to be a big aberration, but hopefully in a good way. But how do you spur this? It can’t stop here. It mustn’t stop here, because as I said, this is the age of biotechnology. And we have a window of opportunity to get it done right. So, how do we expand upon this? And again, with that I’ll go ahead and close. But thank you so much for this opportunity, because at the time it just seemed like a hare-brained idea. But I didn’t realize it would have such a powerful impact on not only one sector but on communities. So with that, thank you very much everybody.

Farai Chideya: Thank you, Ed. Really appreciate it. So thanks again to Ed for showing really unusual models of collaboration. And next up we have one of the MIT Media Lab Directors Fellows, Adam Foss. He’s going to be talking about justice in the judiciary. He’s a former Assistant District Attorney in the juvenile division of Suffolk County’s DA’s office. And he’s the co founder of Prosecutor Impact. It’s a nonprofit that’s developing training and curricula for prosecutors to reframe their roles in the criminal justice system.

Further Reference

“Biohacking and the FBI Ed You at the Defiance Conference,” notes by J. Nathan Matias at the MIT Center for Civic Media blog