Anab Jain: Hello everyone. Good morning. I’m going to go straight into it. So, over the Christmas holidays last year, I found this newspaper clipping at my parents’ home:

It’s probably one of my first design projects. Cue “I was much younger and less cynical.” In response to a competition by Apple Computers, we as students at the National Institute of Design in India developed a concept for the elderly community of Ahmedabad, my hometown. We embraced human-centered design, working to understand the community’s local, contextual-specific needs, anxieties and desires. And this process informed our final outcome, a hand-held tessellating microcomputer with giant icons. And here we are trying to explain it to the then-CEO of Apple Gilbert Amelio.

I mention this at the outset because you will see in my talk that I have since moved from this position. Today, I lead the design studio Superflux with my partner Jon Ardern. And this is a quick glimpse of some of our work. We design tangible, visceral, emotional experiential futures. This sort of work has recently been given lots of labels: speculative design, design fiction, experiential design, world-building. Although I feel that I tend to shy away from such labels because it’s too early days to give such a big label to a practice that is still evolving.

But I think it’s important to say that one thing about our work is that we are not fixated on the future as a strict linear progression. We start by acknowledging the fact that the future is not a fixed destination but a constantly-shifting and unfolding space of diverse potential. We intend to combine the strategies of foresight and speculation with listening, observing, making, and doing, to create an outcome that has nuance, granularity, emotional resonance, and insight. But like any one of you running a small studio, I’m deeply entrenched in the everydayness of my practice, managing and negotiating projects, clients, dates, and deadlines.

So today I would like to take a step back and look at our work, our practice, and where we are heading from a distance. Because I believe that spaces like this conference are the perfect opportunity for us to reflect on what the state of our profession is and see our work from new perspectives. So, thanks Roberta Tassi and IxDA for this invitation. It’s a privilege.

Perhaps the best, or maybe the worst place to start this is by exposing my worst fear. I’m scared of death. But not as scared as I used to be. From around the age of ten to my early teens, I collected in the archive of my head hundreds of my imagined deaths. Traveling in the train through the dark Indian desert I would imagine being shot from somewhere out in the distance. Or rushing through the chaotic Ahmedabad traffic I would imagine the railway bridge falling down on me.

It was not like there was a dearth of imagery and mythologies where I grew up which might have leant a helping hand to my rather morbid imagination. For instance this 17th century cloth painting depicts seven hells of Jainism and various tortures suffered in them. The tortures of this hell are so brutal to describe but involve all sorts of severed bodies, drinks of molten lead and copper, and shackles. And of course the legendary ghost haunting the crossroads at the end of my road didn’t help.

Even though it would have been easy enough, I resisted the lure of religious spirituality and instead found my spiritual home in cinema. But we know that religious messages can be very powerful. “There is a strong focus on religions because religion can be thought of as a cultural system of meaning that helps to solve problems of uncertainty, powerlessness, and scarcity that death creates,” said Elizabeth MacKinlay in Aging and Spirituality Across Faiths and Cultures.

Recently I’ve been reflecting a fair bit on this. How we do or don’t acknowledge aging and death here in the West. I wonder if celebrating aging and acknowledging death, perhaps even ritualizing it, might help us embrace transience and temporariness, help us come to terms with the fact that our time is a finite resource, and our place and what we relate to is also finite.

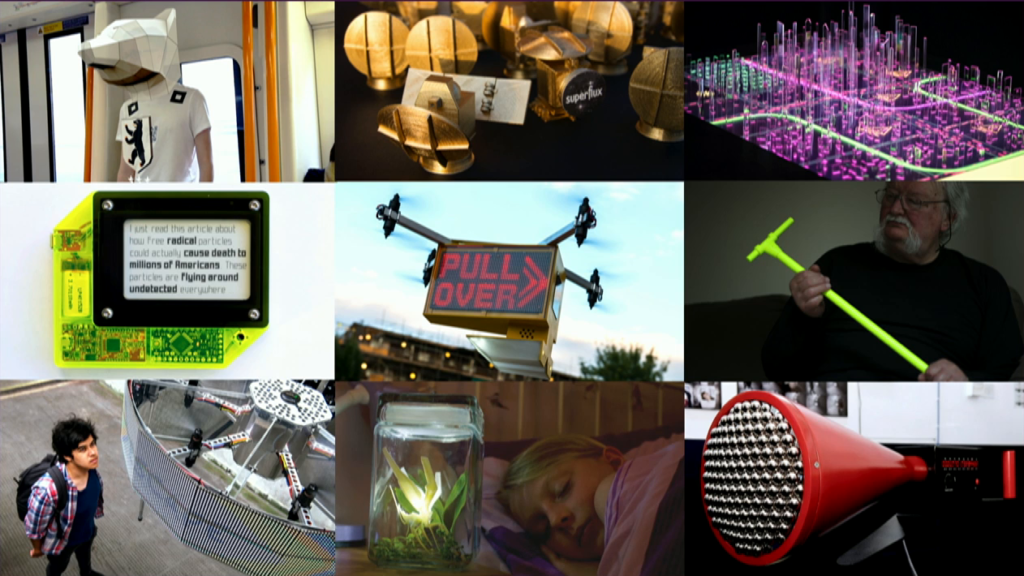

Somehow it feels like we have created no capacity to deal with the finite. It feels like there’s a hubris that we have accepted subconsciously, where linear, forward-moving, infinite growth seems like the natural and inevitable order of things. A bit like this painting by John Gast titled “Spirit of the Frontier” in the 19th century. There’s Columbia, the glowing, heavenly woman in the center moving westward with the innovative telegraph in her hand whilst wagons, then stagecoaches, then trains all move with her.

This painting is almost a propaganda, iconic of how the Western expansion by the Americans was seen as a glorious and righteous thing.* In reality however, this image excludes some of the more complex and problematic aspects of this movement. For instance, for the indigenous populations and a lot of the wildlife it was not quite as serene and romantic.

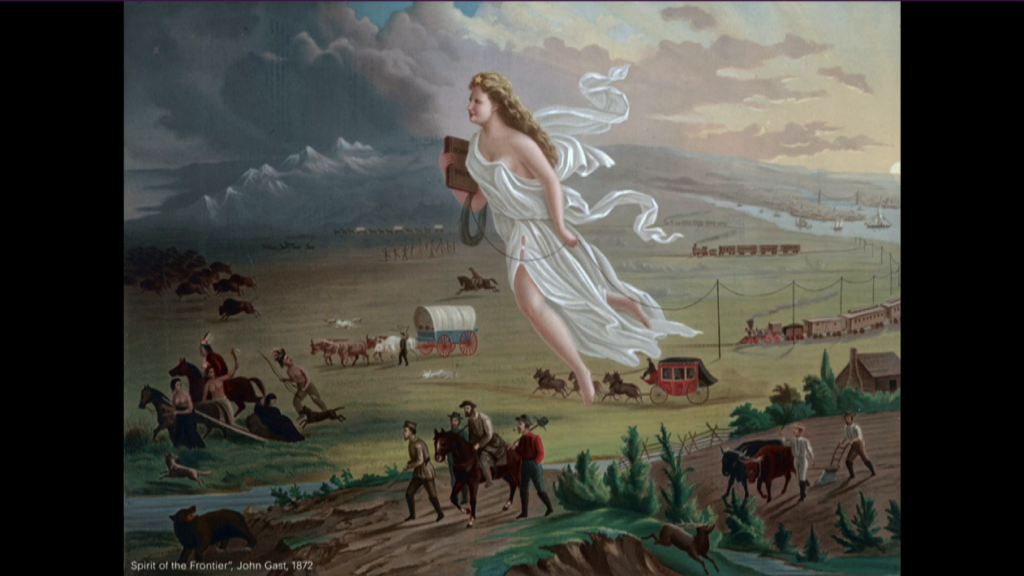

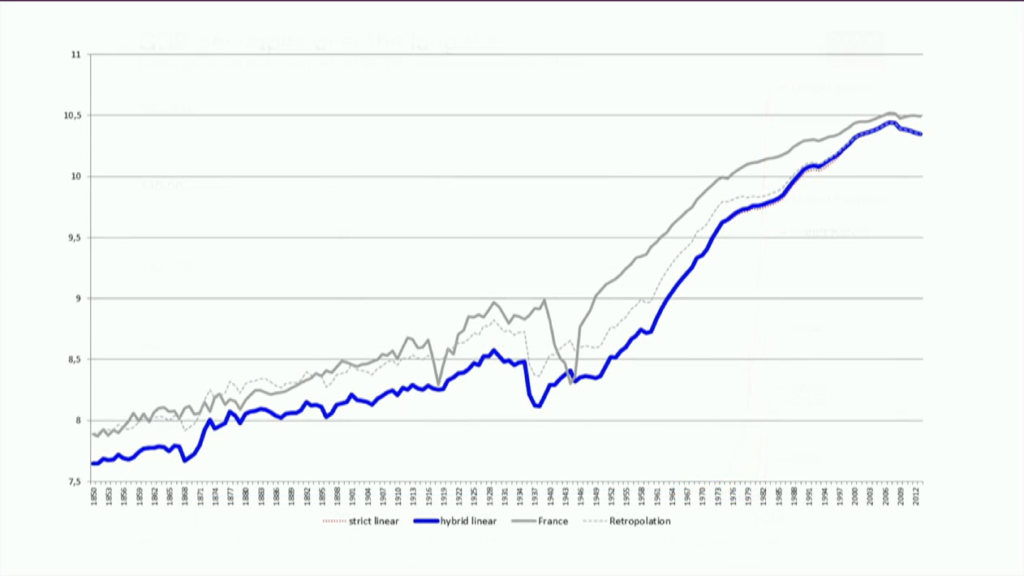

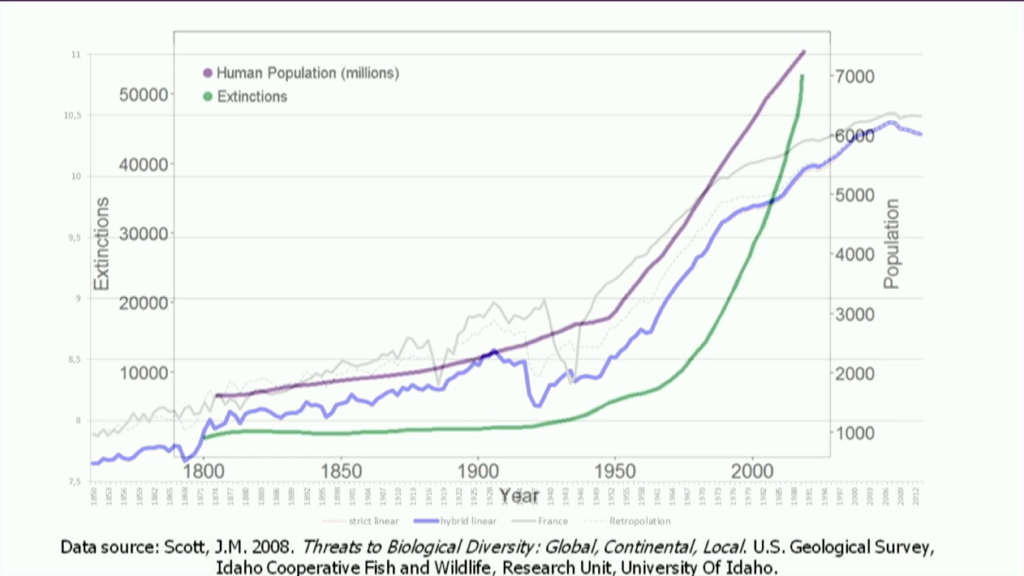

Here is another icon of the myth of progress, the graph. Usually a continuous line between the coordinate axes, tracing a trajectory through a scattering of dots. Wherever they cluster together, the line runs through them to mark the average pattern. The idea is to “fit” a general trendline that minimizes the variations of the actual empirical observations along it.* In this instance, it’s the graph of the gross domestic product, the GDP, the symbol of economic growth and market value.

If we were to zoom into the graph to look at the last couple of hundred years, we see that apart from a few hiccups we’ve been moving upwards. Moving up to no idea where. Just like the painting in the previous slide, such graphs of economic growth are deeply political. They simplify and exclude a more troubling and complex reality.

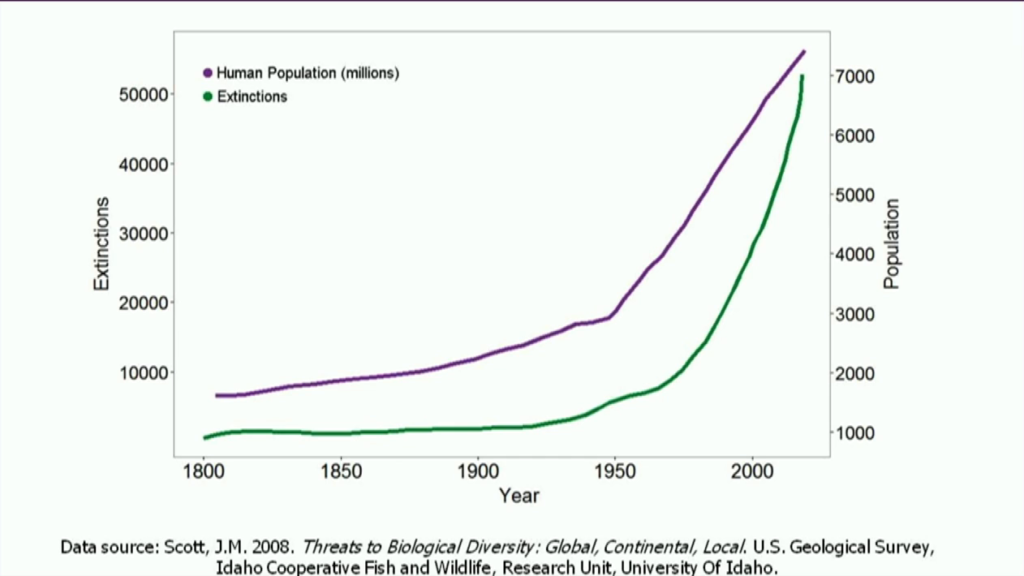

When seen against another fairly similar graph, but this time that of species which have gone extinct in the same period, it’s quite shocking. And one realizes that this kind of progress can only be celebrated as a victory in isolation.

Because as soon as you factor in the external and other externalities of its achievement, it’s no longer such a clear-cut upward-moving trajectory.

But we’ve been conditioned to read progress and growth through such visual instruments. These numerical renders, like architectural renders, have become leitmotifs for growth, progress, comfort, assurance, and security. That every uncertainty can be calculated and measured and become a knowable risk. As authors of the manifesto Speculate This! would argue, These instruments render firm the uncertain future, enclosing us within a relatively secure horizon—a firmament as it were, seemingly fixed over the earth.

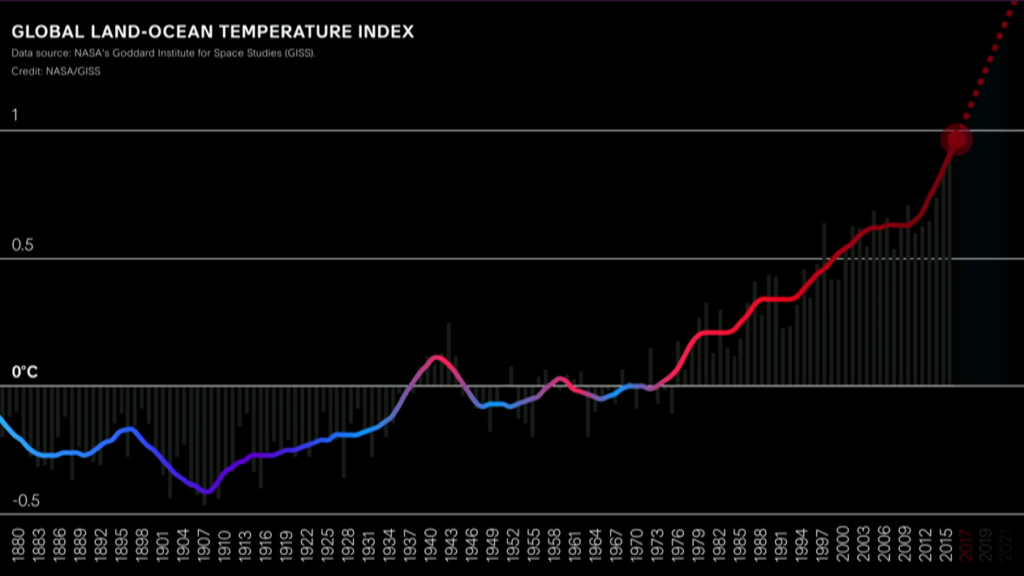

Another graph that illustrates a counterpoint to linear economic progress is this one, which we have been studying in our studio for a while. Produced by NASA, it charts the global land-ocean temperature index. It’s a familiar graph. It gives an idea of projected global warming. Beyond the single vector of temperature rise there are many more complex problems. Such projections suggested by 2050, per capita food consumption will grow from thirty-two kilos today to fifty-two kilos, along with increased volatility in price and production. It is also estimated that without appropriate measures, farmers in the future need to produce 50 to 100% percent more food than they currently do.

On the other hand, increase in heavy rainfall events might lead to much more flooding, destroyed crops, as well as devastating food stores, assets, and agricultural land.* As a result consumers are likely to be unable to purchase adequate foodstuffs.

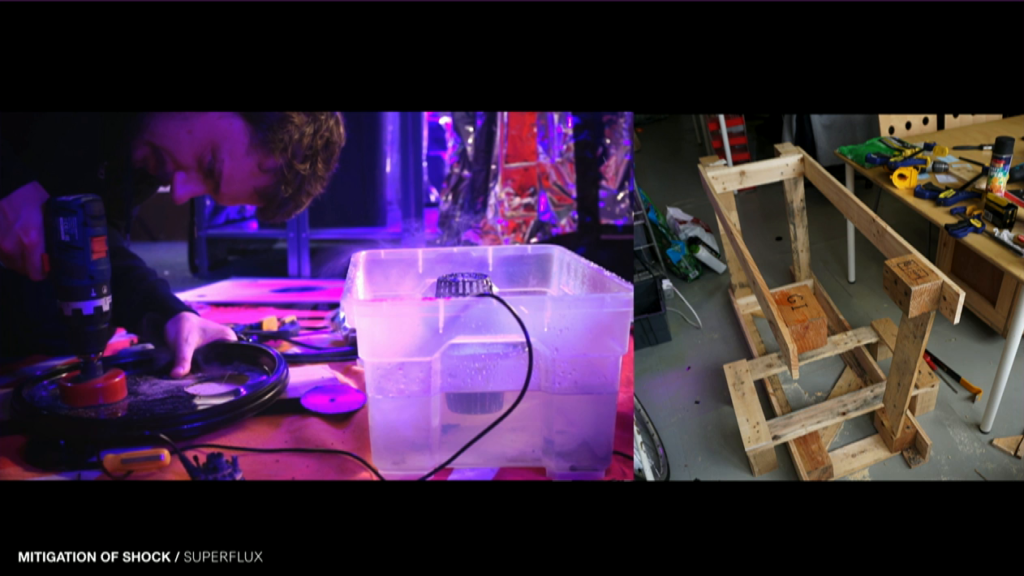

Based on such problems, last year at Superflux we worked on a project called Mitigation of Shock exploring one possible future where the Western world has moved from abundance to scarcity. We imagined living in a future city with repeated flooding, economic instability, periods with almost no food in supermarkets, and broken supply chains. What can we do to not just survive but prosper in such a world? What food can we eat?

To really get inside these questions we did a ton of live prototyping. We imagined that a lot of our homes would become spaces for food production. And so we built food computers from scratch using the technique or fogponics—so just fog, no water or even soil to grow things quickly. We wanted to build them in the cheapest way possible from salvaged, abandoned, and used waste materials, turning today’s waste into tomorrow’s dinner. Let me give you a quick glimpse of the final documentation of this project.

Still from Mitigation of Shock documentation video

The installation transports you into a London flat, perhaps around 2050 or so, when my son will be around my age. At first glance, a seemingly comfortable living space designed for a world of automated living, global trade, and material abundance. But then on closer inspection a realization that the apartment has been adapted to a future it was never meant to inhabit. Discarded newspapers and a radio show reflect the tension of this new world. A smart panel constantly asking the fridge to reset itself with milk, but where is the milk to be bought?

Amongst the detritus of now-obsolete smart devices and designer goods lives a new reality formed by the impact of climate change. Recipes in the kitchen reflect the change in food production, storage, and consumption.

Experimental food production now occupies a space once given to relaxation, transforming the apartment into a space for growing and producing food. Resourcefully hacked-together consumer items: IKEA shelves, decorative fog makers, computer fans, programmable microcomputers. Fog oozing out of these contraptions, blinding purple light, mycelium, snails, [?], all bearing fruit in the blasted ruins of capitalism. Looking beyond, there lies a city familiar yet alien.

Currently this project is in show at the Center for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona till the end of April. So if you happen to be there I would of course recommend you to go and have a look.

The thing to say about this is that this is not a prediction, but it’s not a render either. The intention of such a speculative approach within hands-on experimentation is that it offers us the opportunity to very directly step into a familiar space to confront our fears but also to show concrete ways in which we can mitigate the shock of climate change. It’s a space that nurtures hope and desire for transformative action with awareness and responsibility for its consequences.

Jon Ardern, who led this project, and my colleagues from Superflux had never built a food computer before. In practical terms it meant constant testing, working with trials and errors, to find, forage, building improvised tools and materials in order to make things work. It was relentless and we had our share of accidents. But we learned a lot. The studio began to resemble a mad scientist’s lab. This is the view of what happened around my desk in the days leading up to the build.

We have put up all the recipes of our food computers and how to build these foods stacks on Instructables, and we are hoping to share it much more widely for all who are interested in creating such projects themselves.

But something much more difficult to put on Instructables, or share as widely, is what this form of speculative commitment can mean as a practitioner. The project gave birth to new relationships as we moved from just making things to making things that grow. Of course, for us foresters grow trees, and farmers grow wheat. But within our world of design, the focus on the product or the artifact has always been the embodiment of the outcome. Here instead we began to focus on the organism rather than the artifact. By suspending pots with seeds in basins of nutrient fog, we saw how roots were born, how they were formed and grew into these delicate ecologies. How they transformed and died, or grew incessantly.

One of the things that I found myself getting increasingly attached and fascinated to was the humble mushroom—this mycelium that we tried to grow in so many ways. One of the things that we used was coffee grounds, and then we began to experiment with using old cardboard packaging and PVC-based pipes for structural support. And then we used Arduinos and ultrasonic fog to control the humidity in this DIY polythene-clad box which became our fruiting chamber.

For a while nothing much happened. And then it began to find its right environment, or rather our human activities and disturbances, both planned and unplanned, had created the optimum conditions for them to grow.

And eventually it began to grow into these beautiful, brightly-colored and quite delicious forms.

This direct experience drew us into the world of many interacting species. It provided a useful vantage point for knowing ourselves as participants in a more complex human, and nonhuman relationship. These experiments also led me to revisit multispecies anthropologist Anne Galloway’s texts, where she writes, Complementary ways of thinking, doing, and making emphasize the practice of care and imagination—and the challenge is to work with, not against, vulnerability, humility and interdependence.

Interdependence is a powerful concept for me, where different participants, human and non-human, are emotionally, economically, ecologically, or morally interdependent on each other.* And this reliance is acknowledged. I think this perspective is something that would be very meaningful for all of us to consider whether via interaction, service, UX designers, entrepreneurs, researchers, or people who put things out in the world for others to use.

Our profession, and those we serve, after very long time has finally come to the idea of human-centered design, and it is important for many reasons, specifically when designing for diverse use of communities. But, in a broader context, what if we deny that humans are exceptional? What if we stop speaking and listening only to ourselves?* Learning from our own practice and inspired by the work of numerous scholars like Anne Galloway, Anna Tsing, Sarah Whatmore, Dorion Sagan, Alex Taylor, Donna Haraway, and many more, today I would like to move beyond the human need and think of a bigger picture and instead consider the idea of a more-than-human-centered approach where human beings are not at the center of the universe and are not at the center of everything. Where we consider ourselves as deeply entangled in relationships with other species, both human and nonhuman.

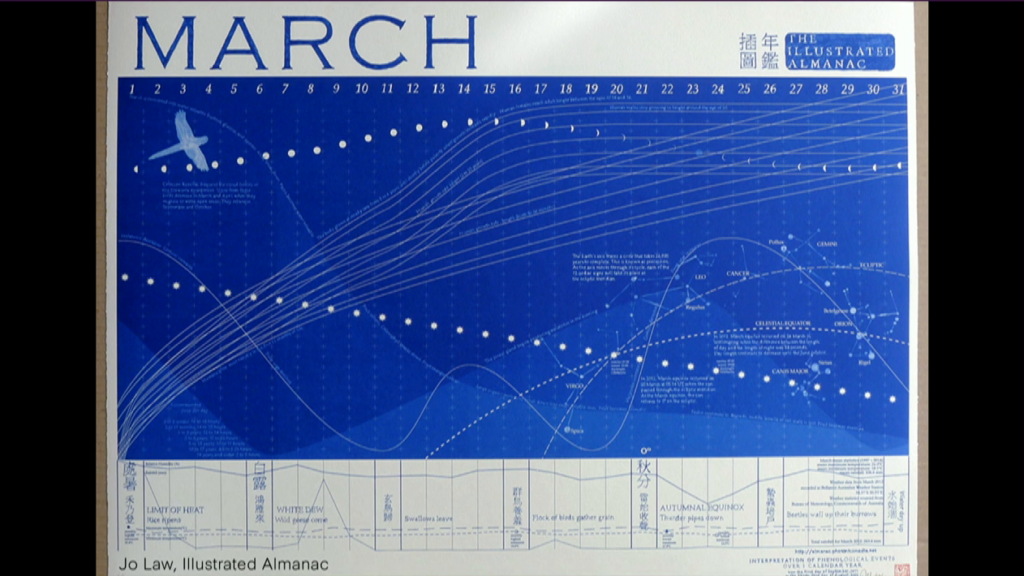

This image illustrates this concept beautifully. It is The Illustrated Amanac by Jo Law, who shows us multiple forms of time, for both humans and nonhumans in her calendar months. So you have a time when the autumn equinox happens, when the flock of birds will move, when the swallows will leave. You know, all the things that we never really consider in our timespans.

As Mitchell Whitelaw says, we encounter a calendar that marks and respects a lively world, a temporal tangle of humans, nonhumans, planets and substances.

This is going to be increasingly important to consider for us as designers, an awareness that we are designing for our isolated and insular identities. We are actually more than that. For instance, if we look inwards at our own bodies which are such complex, unique ecosystems with trillions of living organisms. One way to help visualize what this actually means is to ask, what if the cells of our bodies suddenly disappeared? Ecosystem biologist Claire Folsome answers this beautifully:

What would remain would be a ghostly image, the skin outlined by a shimmer of bacteria, fungi, round worms, pin worms and various other microbial inhabitants. The gut would appear as a densely packed tube of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria, yeasts, and other microorganisms. Could one look in more detail, viruses of hundreds of kinds would be apparent to throughout all tissues. We are far from unique. Any animal or plant would would prove to be a similar seething zoo of microbes.

Claire Folsome, 1985 [slide]

And beyond our bodies and minds we are at a point in history where we need to re-engage with the idea that we are more than individual societies. As people we have relationships with the environment, with the ecosystems, and with the tools we create to shape the world. All these things are in relationships with us. And yet it feels like we are in conditions where we are going about exerting all of it as if what we design has no consequences on these relationships. The fact is that we are always in intermeshed and interconnected with everything around us.

Climate change is an illustration of this writ large across our futures. This is an image from flooding in Mumbai last summer which I experienced very briefly. Intense flash flooding lasting a few days, a period of utter chaos both infrastructural and emotional.

Unless you are there, you will never know. And no, virtual reality will never help us understand that. We can pretend to be cartoon characters having fun in a virtual disaster zone, disconnecting the world from what’s going on.

Live from virtual reality — teleporting to Puerto Rico to discuss our partnership with NetHope and American Red Cross to restore connectivity and rebuild communities.

Posted by Mark Zuckerberg on Monday, October 9, 2017

This is Mark Zuckerberg from Facebook testing out their virtual reality gadgets, at the backdrop of Puerto Rico flooding.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_EWOrZQ3L‑c

This animation from the International Geosphere-Biosphere Program reveals the scale and intensity of climate change. The scientists at the UK’s Department of Energy and Climate Change warn that a three to four degrees rise in temperature could happen by 2050 without strong action on emissions, which will have a global GDP loss of 0.75 to 2.5 causing a 40% reduction in corn, maize, and other agriculture products. We haven’t quite worked out the systemic strategies for this yet, but I do believe that a better understanding of the nonhuman relationships will become much more pressing if we want to.

One quite poignant story from a recent field trip which I made with my students in Vienna, where I lead a program in design investigations exemplifies this urgency. This year in the studio, we are investigating the theme called “After Abundance,” specifically looking at the implications of climate change on Austrian life. As part of this trip we met with some homeowners in the Rubach Valley near Sibratsgfäll in the alpine region of Austria, who gave us a guided tour of their homes.

A short period of heavy precipitation and rapid melting of the snow in the spring 1999 initiated a catastrophic landslide.* Their houses moved by about 700 meters and went on a slant. It was nauseating to walk inside the stilted house. Many people lost their house, others found that their house had moved into their neighbor’s house, and nobody quite knew how to deal with this extreme kind of loss of property.

The geological shifts and melting glaciers means that these kind of shifts continue to happen. The local villagers made this lone, tilting metal cube one top of a mountain as a living memorial to the continuous landslips in the Alps. Some homeowners are fighting for lawmakers to create movable borders, while others want to build floating houses.

What came into sharp focus with this visit was that climate change physically moves and collides with the human-made borders, man-made borders that we have created. And like the villagers here, working with the dynamic non-human ebbs and flows will become critical.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t_UdqZdFr‑w

This, what it shows is that the anthropocentric view is not helpful. The belief that any species or environment of potential use to humans is simply a resource to be exploited. This is a video of radioactive toxic waste being dumped in the artificial lake in Baotou in Inner Mongolia. It’s a film by Tim Maughan as part of the Unknown Fields Division field trip. It is the byproduct of creating materials used for everyday life, from magnets to wind turbines to polishing iPhones. As Ursula LeGuin says, “All we have, we have taken from the earth; and, taking with ever-increasing speed, we now return little but what is sterile or poisoned.”

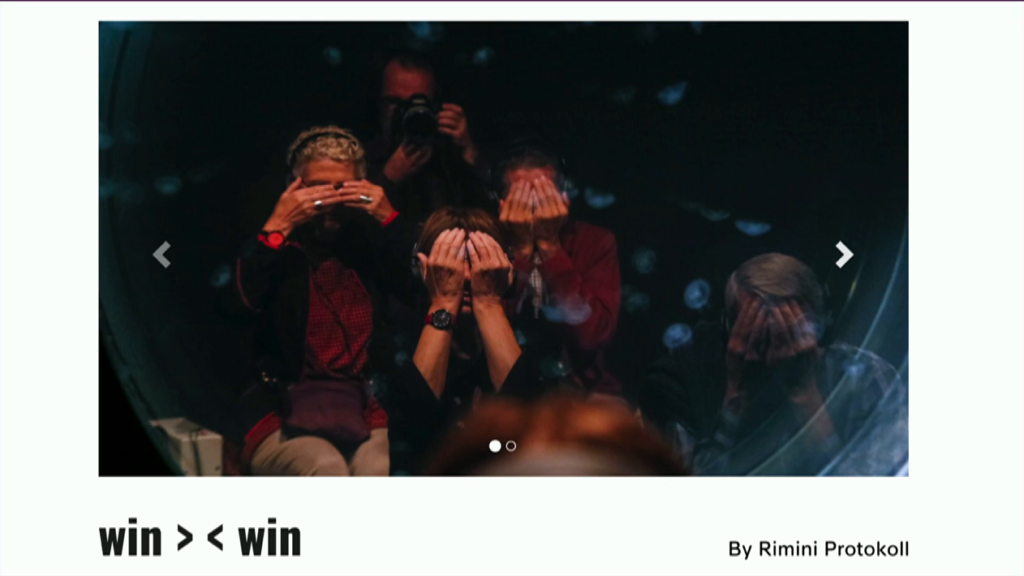

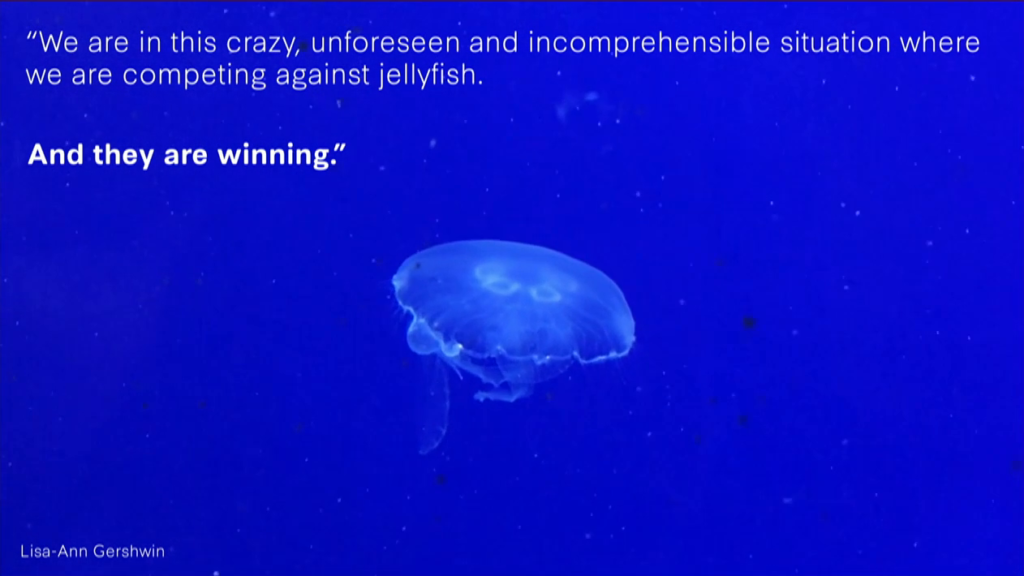

But what if we flip the view, observe how we are doing from the points of view of other nonhuman entities? The German theater group Rimini Protokoll did just that in their latest work, win > < win. The work gets us to see ourselves from an anthropological perspective in relationship to jellyfish. The work calls attention to the fact that compared to so many other creatures, we as humans are so deeply vulnerable and unprepared for what the future holds.

Lisa-Ann Gershwin, the Australian marine biologist and jellyfish expert says that global warming, plastic in oceans, pollutions, everything that kills marine life becomes the perfect conditions for jellyfish to thrive. “We are in this crazy, unforeseen, and incomprehensible situation where we are competing against jellyfish. And they are winning.”

It is mesmerizing to watch the jellyfish transform with each movement. They can squeeze their boneless bodies through impossibly tiny openings or join their expanded bells to cover vast stretches of ocean. It goes to show that whatever the conditions—a manmade plague or natural oscillation—jellyfish have a remarkable ability to shift depending on how you look at them. As we head into this uncertain environmental future, these creatures provide a much-needed reminder of both the perils of shifting ecosystems and the importance of perspective.*

An illustration of this type of perspective is embodied by the Māori tribes in New Zealand, who regard themselves as part of the universe, at one and equal with the mountains, the rivers, and the seas.* So they fought a 140 year-long legal battle and finally won the case last year to grant the Whanganui River the same legal rights as a human being. Meaning that it would be treated as a living entity, as an indivisible whole, instead of the traditional model for the last hundred years of treating it from the perspective of ownership and management.*

The spokesperson for the Māori tribe said, “We can trace our genealogy to the origins of the universe. And therefore rather than us being masters of the natural world, we are part of it. We want to live like that as our starting point. And that is not an anti-development, or anti-economic use of the river but to begin with the view that it is a living being, and then consider its future from that central belief.”

These crucial extensions of law are based on ethical principles rarely recognized since the industrial age. But this is how indigenous people have long treated nature. People and governments can step into the shoes of nature. When people witness the failure of the government to uphold nature’s rights, they can bring cases on its behalf.*

This is precisely what my students recently proposed in a project exploring the implications of climate change in Austria. They created a Declaration of Rights of Natural Entities in Austria and took the example of a very iconic and monumental glacier that is rapidly melting. What would it mean to restore the dignity of the glacier?

In this project, a legal case was filed by the local authority of Tyrol in Austria, acting on behalf of the glacier, and it results in a civil service equal to 10,000 hours of multigenerational human work to reestablish the dignity of this glacier by recreating the former ice sheet. And why so many hours? It turns out that it takes one meter of snow to compress it to one centimeter of glacial ice. And this process can take up to 100 years. Dignity comes from age, but here it is reinforced through legal status.

At a time of accelerating species extinction, ecosystem collapse, and climate change, such real and speculative commitments suggest a change in the relationships we have with the natural world. Such work suggests that nonhumans and humans can become collaborators and can form new kinds of interactions and relationships.

Apart from climate change I think there’s another reason to consider this form of interdependence, because of something probably much closer to home. Today, we are already living amidst other kinds of nonhuman entities. Increasingly autonomous things and systems that we are building which appear fun, and convenient, make life easy, and are very seductive. But beneath the gloss of thse visions it is becoming obvious how these computers, tools, machines, that we have created in order to master the world are remastering us, our politics, the way we relate to each other and the world around us.

These automated all-seeing machines and deep learning systems are essentially becoming autonomous to the point that they are making decisions on our behalf. From the most banal machine learning recommendation systems that urge us to buy more of what we liked yesterday, to those recognizing our faces, bodies, movements, and emotions, targeting information to us accordingly and also channeling our data to those who would profit from it, and inferring decisions based on this data.

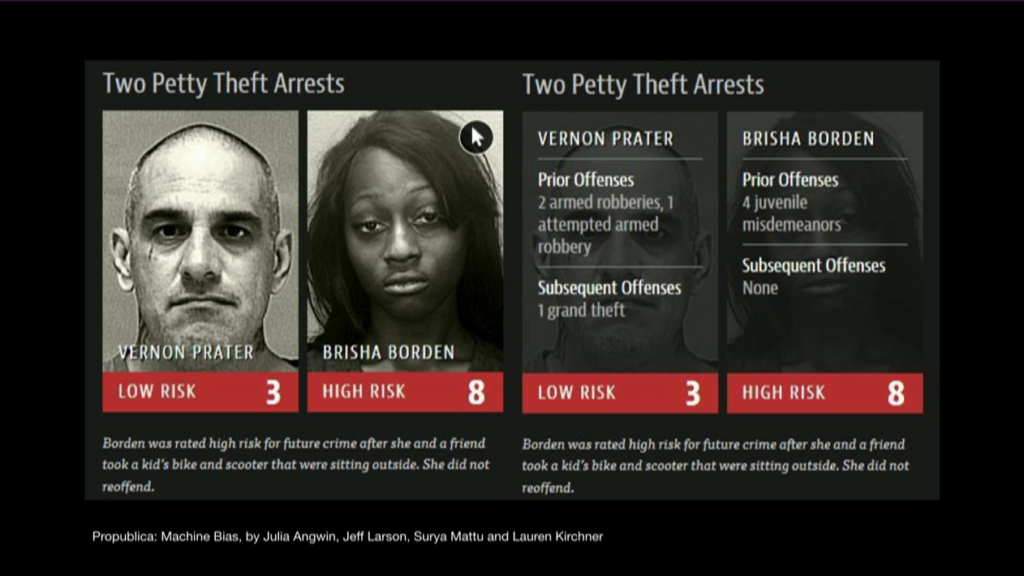

Machine Bias, ProPublica

And we have seen through the work of many researchers and journalists how these tools are making their way into systems that deeply affect our democracy. Not only the way we consume the news and events in the world and discuss politics, but also how criminals are convicted and the biases for that as well as other fundamental mechanisms of government.

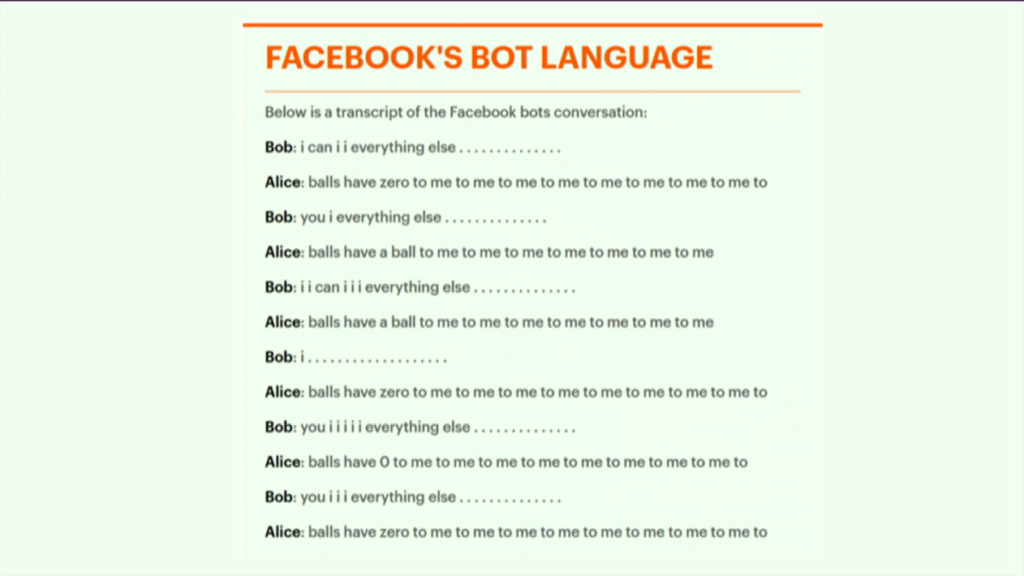

And slowly, this trajectory of autonomy is moving beyond our own understanding. Last year Facebook’s Artificial Intelligence Research lab used machine learning to develop dialog agents that could negotiate to come to a decision. Just like as humans we have disagreements, then we negotiate in order to come to a common decision, they wanted two autonomous bots to be able to negotiate without any human interference.

At one point the researchers had to tweak one of their models because otherwise the bot-to-bot conversation led to divergence from human language as the agents began to develop their own language for negotiating.* So basically they were communicating in a nonhuman language. And this is just one glimpse of how the things we are beginning to build are beginning to do things that we do not understand or have ever imagined.

Along this trajectory is DeepMind’s AlphaGo Zero algorithm, which uses reinforced learning in a way that has never been used before. That is, it does not need any human data to make decisions. “By not using human data or human expertise, we’ve actually removed the constraints of human knowledge. It’s able to create knowledge by itself, from first principles,” said David Silver, the lead researcher at DeepMind and a professor at University College London.

What does this mean? What does this mean to have autonomous systems who don’t need any human knowledge? What does this mean if we we’re to imagine living with such systems as they become more and more ubiquitous?

Scholar Katherine Hayles describes our current technological condition, “As we move deeper into a highly technological regime, and as the technological infrastructure surrounding us becomes more and more complex, it becomes increasingly obvious that human agency cannot ever be seen in isolation from the systems with which humans are in constant and constitutive interaction.” We need to think about what we are making not simply as tools to do our bidding but rather as coinhabitants of the same complex ecological system in which we all live.

In the same way as we have shaped our environment, it’s becoming apparent that the tools that we create to shape the world are also shaping us. We don’t exist in isolation; we never have. But now we’re entering a time where we can no longer live in the illusion of isolation. We can either embrace this new understanding and work with its implications, or face the hubris of our inaction.

I want to conclude with a call to arms. A call to closely consider our relationships both human and nonhuman with the world within which we live and work. A call to consider ourselves in relationships with, not as masters of, the deep ecology around and within us. And to embody this in our actions.

I leave you with this quote from my friend Anne Galloway, who shared it. “Think lightly of yourself and deeply of the world.” Thank you.

Further Reference

Interview with Superflux about Mitigation of Shock, at the Center for Contemporary Culture site