Kris Howard: Okay. So, just so I know what I’m dealing with here, how many of you have ever knitted in your entire life? Oh sweet, like everybody. That’s really good. If you’ve got them, and I know we do have knitters in the audience, please feel free to whip it out, knit along— [indistinct; mic issue] Feel free to knit through the talk. I love that.

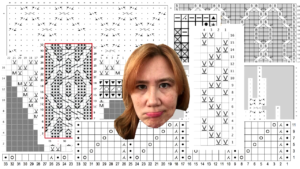

As for the rest of you muggles… [laughter] Don’t worry, no prior experience is assumed, and I’m not going to teach you either. I’m here to talk about code, after all. So my goal is to convince you that this…

…is actually more similar to this…

…than most people realize.

Because really when it comes down to it, this is actually this:

And to computer programmers, that looks a hell of a lot like computer code. And you don’t need take my word for it. I’m sure some of you saw a month ago some engineer at Uber tweeted this…

How the f. can people think/say that women can’t write code, this is straight up assembly. pic.twitter.com/GiikM0ERue

— Louis Opter (@1opter) December 17, 2016

…and it went viral, and everybody like sent it to me. Because even though I’ve been saying it for years when like a dude says it suddenly it’s novel.

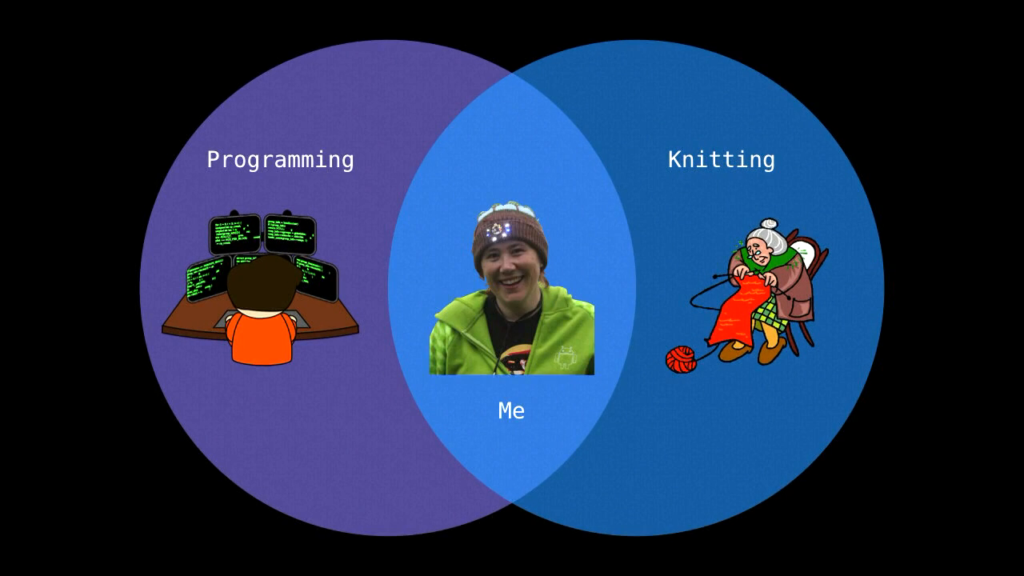

But snarkiness aside I’ll introduce myself. So, I’ve been working in tech a hell of a lot longer than I’ve been a developer. I’m sorry. A hell of a lot longer than I’ve been a knitter. So tech first. I grew up in the US, and I worked in London for a while before I moved to Australia in 2001. And when I got here I had to wait a while for my work visa to be approved. And, young person, we didn’t have Netflix back then.

So I decided to learn a hobby. And I thought I’ll learn to knit, right. Like, how hard can it be? I mean grandmas do it, right. It’s totally offline, totally separate, totally simple—I’ll get a nice fuzzy scarf out of it. I can do this.

So I get a kid’s learn-to-knit book and I started making a potholder. And it nearly killed me. I think I started over about a dozen times. And by the end of that project, I had three things.

One, I had a really kickass pot holder, which has pride of place in my house today. Two, I had mad respect for the grandmas of the world, like you have no idea. And I had the revelation that knitting was just like coding.

And this just blew my mind and I started seeing these similarities everywhere. And pretty soon this mental model:

Became this:

So, today I’m gonna walk you through some of those areas of similarity, and the patterns that I recognized, in the hopes it’ll just inspire your own creativity. Look, this isn’t something you’re gonna learn in your job. It’s nothing you’re gonna need next week. But I really believe that by looking at what you do in a new way, it makes you better at it.

So lesson the first, if you learn nothing else from linux.conf let it be this.

This? This is not knitting. [laughter] Not knitting. This is crochet. This is not contempt culture. I’m not looking down on the hookers here. Crochet is a perfectly valid form of expression. It is not knitting, though. So it uses a single hook. It’s got a ball of yarn, you make stuff. Crochet’s really great for complex three-dimensional shapes. And if you’re into math go home tonight and Google “crochet maths,” and then next year you can be up here doing a talk on crocheted hyperbolic geometry.

This is knitting. Knitting is done with at least two needles, sometimes more. It’s involves the sequential processing of stitches from one needle on to the other.

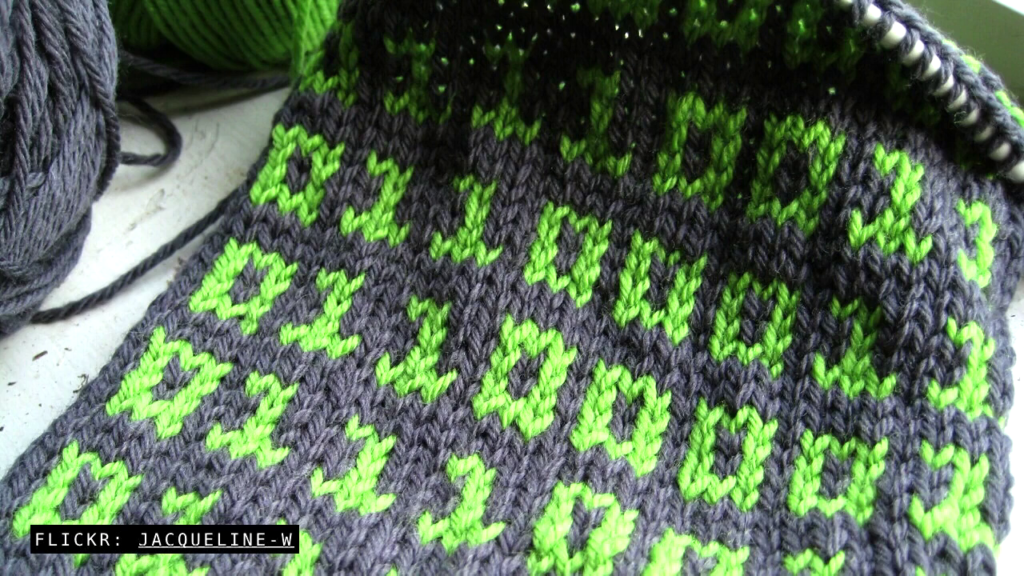

Now every knitter learns when they start out that there are actually really only two stitches: knit and purl. So the first thing I realized right off the bat was knitting’s binary. And to a computer geek like us, that implies I can use it to encode pretty much anything digital. And I started seeing examples of this everywhere.

So for example I could combine knits and purls to make ribbing for a beanie, like for hat. So this is called the Decoder Hat by Zabet Stewart, and it encodes up to twelve characters, in ASCII, in binary, at eight stitches per character. So obviously that is a pretty hard memory limit, a message length of only twelve characters, determined of course by the size of your own head.

Now if you wanted to knit something longer, you could knit a scarf. So this scarf here is the source code to ravelry.com, which is basically Github for knitters, with knits as the ones and purls as the zeros.

Now, if you’re more of a blackhat you could even knit a virus. In 2001 a team of activists did just that. They knitted the source code to the Code Red computer virus into a fluffy red scarf. You could wrap it around your neck and walk across any border in the world. No firewall’s pickin’ that up.

If you wanted something more stylish you could do cables, I’m a big fan of cables. The hat on the left here represents the numbers from zero to fifteen in binary notation depending on where the cable crosses occur. And the scarf on the right has a hidden message in binary revealed by cables that actually look like little ones and zeros.

If you prefer color you could use the width of knitted stripes in different colors to encode a character set. The stripes on this guy’s jumper of course spell out the classic first programming exercise—say it with me, “Hello, world.”

If you want to get super literal you can actually knit ones and zeros into your scarf. I’m happy to tell you the average scarf, depending on how tall you are, will hold about 120 bytes of information. Just shy of a tweet.

Of course not all data is text. Did you know in World War II the Belgian resistance recruited little old ladies who lived near trainyards to watch the German trains and secretly knit their movements into their projects. It’s true, I saw it on QI.

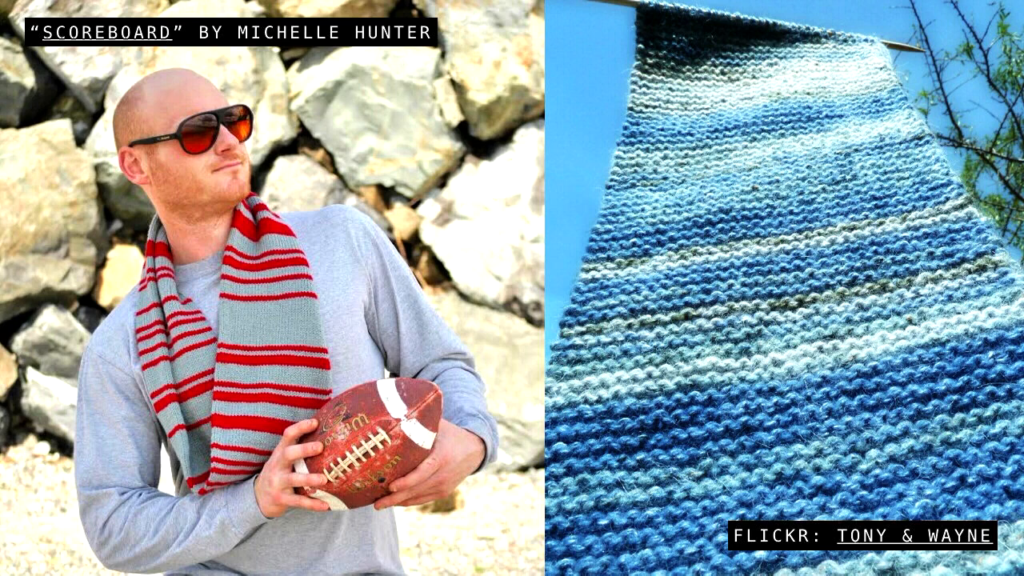

In more mundane examples, on the left here is the Scoreboard scarf, which is a record of a sports team’s season, with all of their points in one color and all their opponents points in another color. I really hope he’s barracking for the grays. And on the right is a sky scarf, where the color of every row is the color of the sky above the knitter on the day that they knitted it.

Now my last example of knitted and encoded data actually won me a second prize at the Sydney Royal Easter Show a few years back. So ladies and gentlemen, I give you the knitted QR code mitten. It does work. It was surprisingly difficult to get it to work. I mean, QR codes rely on things being really square and knitted stitches as some of us know are inherently wider than they are tall. So I had to do a lot of prototypes on different thicknesses of wool, and eventually got— I hit upon the solution, which in technical terms was to stretch the hell out of it…and then eventually got one that reads. So if you scan it, it points to a URL on my website that has the pattern for the mittens. So they’re self-replicating.

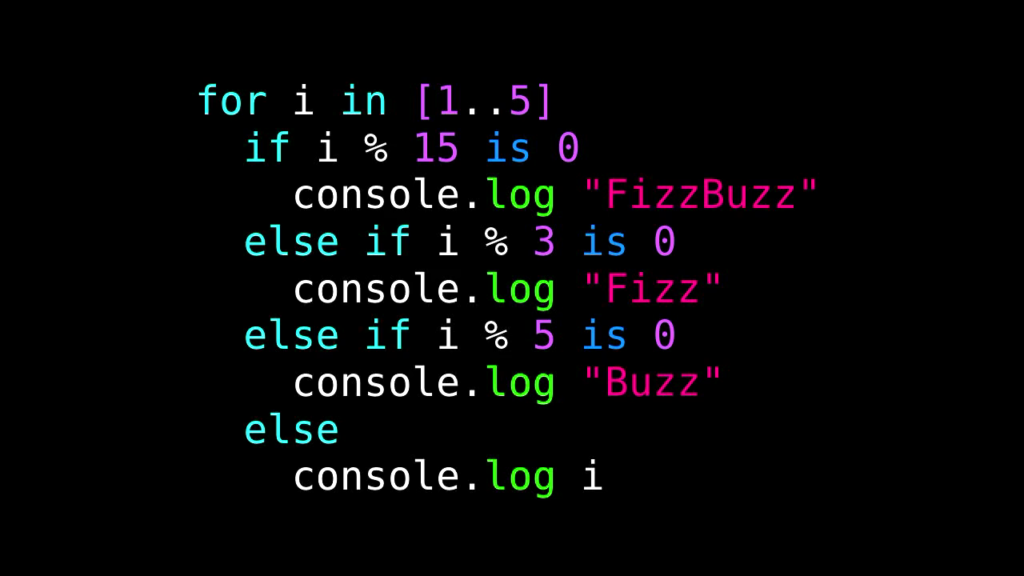

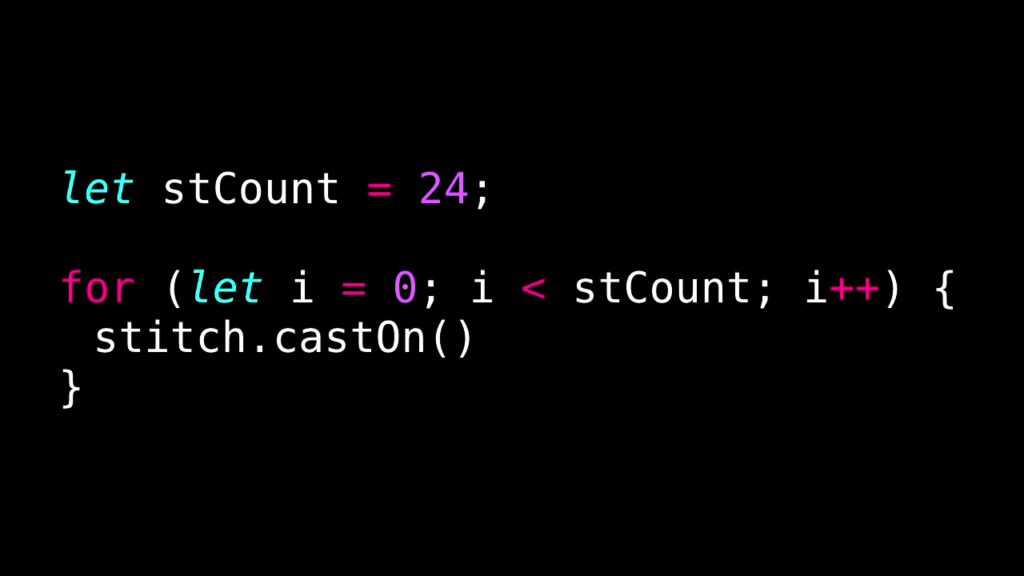

Okay, so back to my story. So once I had the basic mechanics of knits and purls down it was time to learn to read patterns. Now the very first line of any knitting pattern looks something like this, “Cast on 24 stitches.” And that means to create that initial row of loops on the needle. Well I looked at that and my brain immediately recognized well that’s just a for loop. You know, it’s code executing repeatedly a certain number of times. So my brain kind of translated it into code. You know something like this, like a very simple little for loop with a variable that calls stitch.castOn() 24 times.

Okay. I can do that.

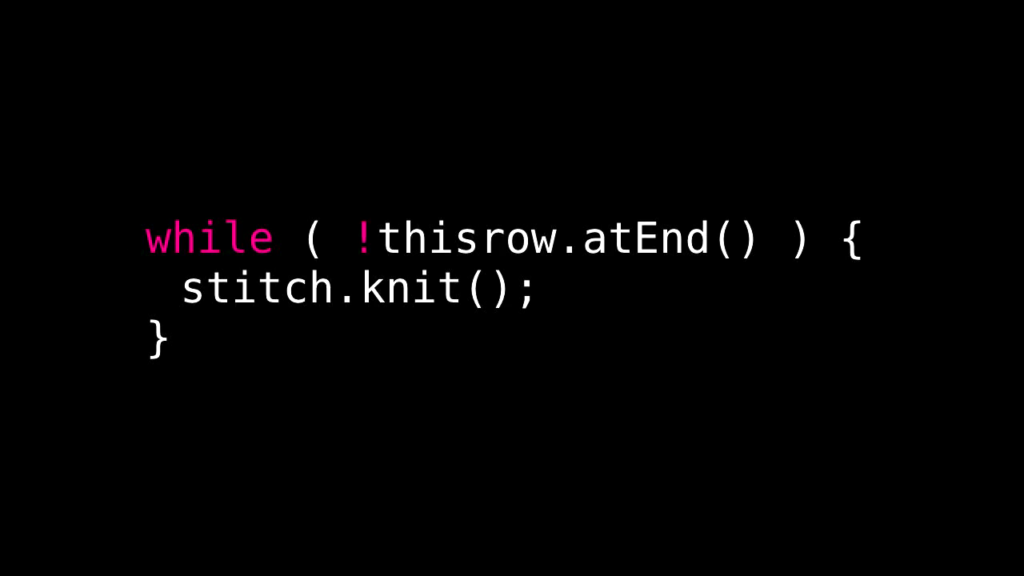

So another really common instruction you see is “Repeat to end of row.” Well that’s a while loop. So you get code executing repeatedly again based on a given boolean condition, and the condition in this case being “have you gotten to the end of the row yet?” If not, keep going. So again, really simple little while loop. While the expression “not at end of row” is true, just keep knitting.

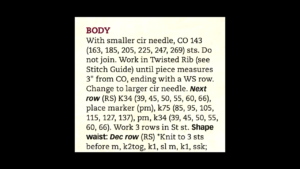

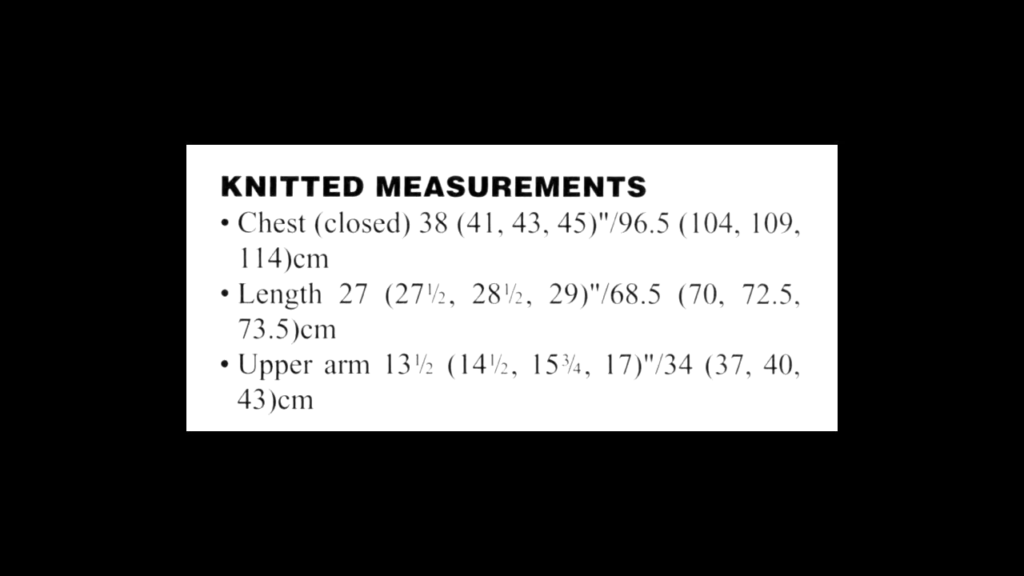

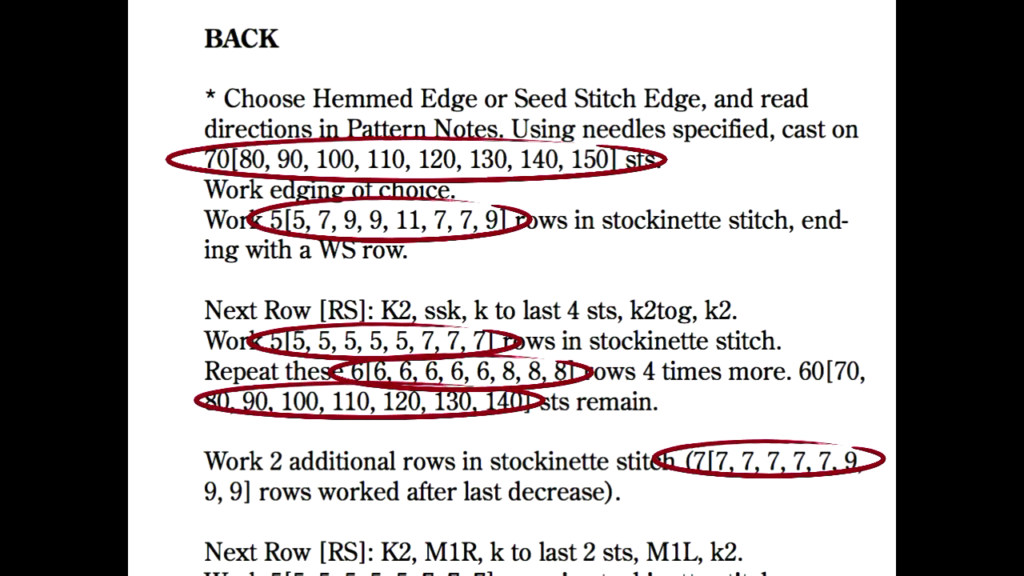

So that was all making sense. So once I finished my potholder eventually, I was itching to move onto garments. And I picked out a jumper pattern, I opened it up, and the first thing I saw was this: “Cast on 242 (256, 270, 284) stitches.” So I puzzled through that and I realized these correspond to sizes.

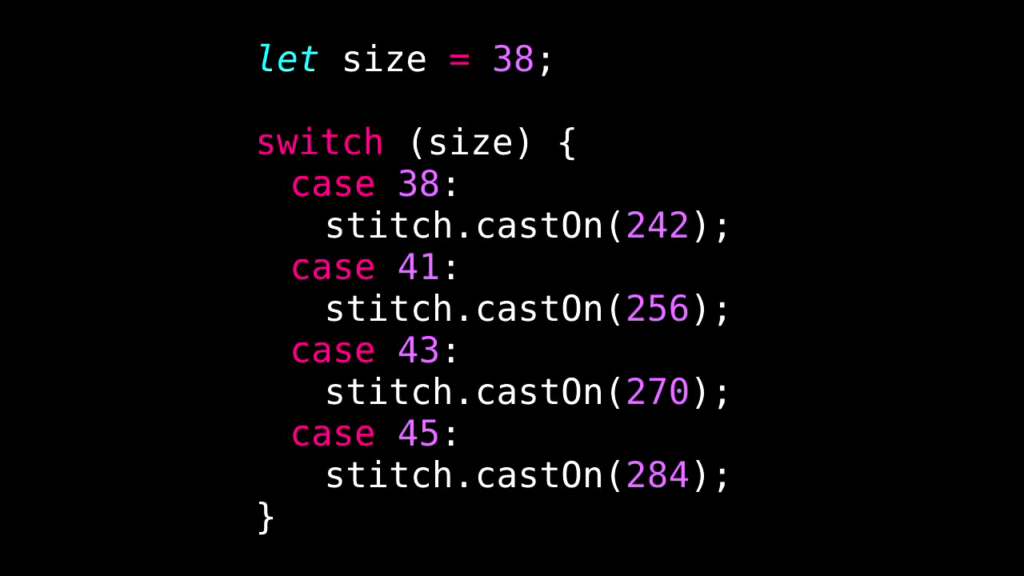

So, there are four garment sizes at the start of the pattern. So here’s an example for a cardigan. So let’s assume I want to knit the 38″ chest size. Then I just need to cast on the number of stitches that correspond. So the first one of every group before. So really, this is a switch statement. This is code that allows the value of a variable or expression to change via multiway branch.

And so I set a variable for my stitch size and then based on that I cast on the appropriate number of stitches. So in this case 242.

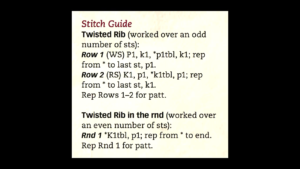

Now some patterns especially if they’re for kids and adults have a lot of switch statements. And each case usually involves more than just a single variable changing. So you might have whole sections of the pattern you use or don’t use. And that leads me to the next concept, subroutines. So you know, in a program we might call these procedures or functions or methods. Well these are everywhere in knitting. You know, if a pattern uses a particular stitch pattern, they get declared in a separate block at the start and then just invoked wherever you need.

So here’s an example where a pattern has two specific stitch patterns, “Twisted Rib” and “Twisted Rib in the round.” And then in the actual instructions, the twisted rib function is invoked with the phrase “Work in Twisted Rib.”

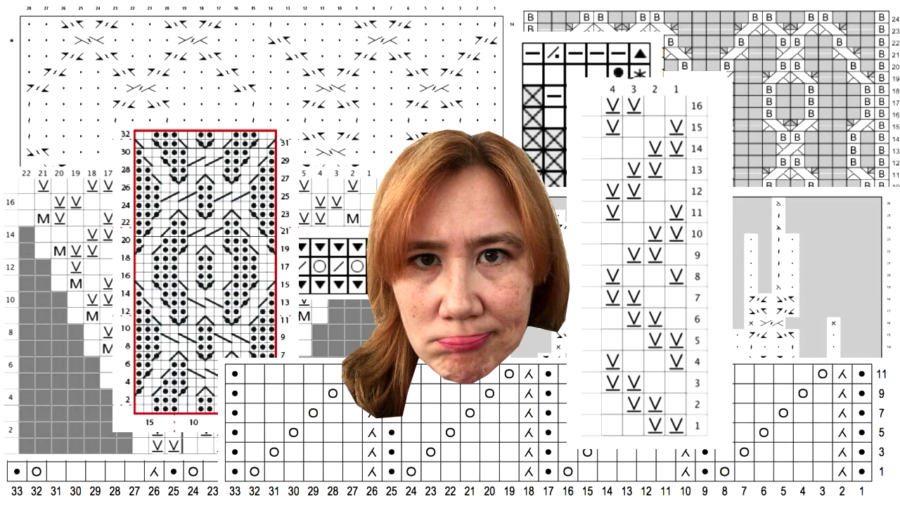

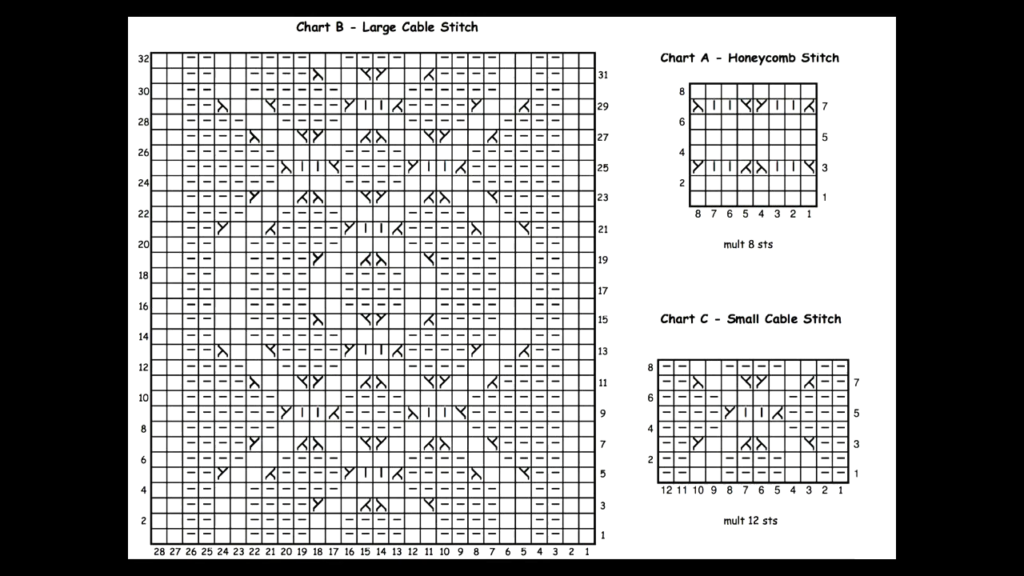

Now another way that patterns declares subroutines is with charts, especially if they’re complicated. So here’s some examples from a cable cardigan, you know. There might be one chart for the front, one for the sleeve, and one for the collar. Now the real fun happens (and the knitters know this) when you have more than one of these subroutines happening at the same time. And that actually takes us into the realm of coroutines, which some of you know are a special class of subroutines. So subroutines start and finish and don’t hold state. But coroutines can exit my calling or yielding to other coroutines and then later come back to the point where they left off. It’s like hitting the pause button. And you can also have multiple instances of a given coroutine at once.

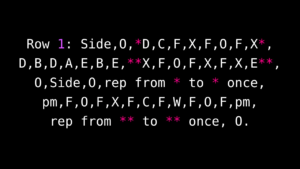

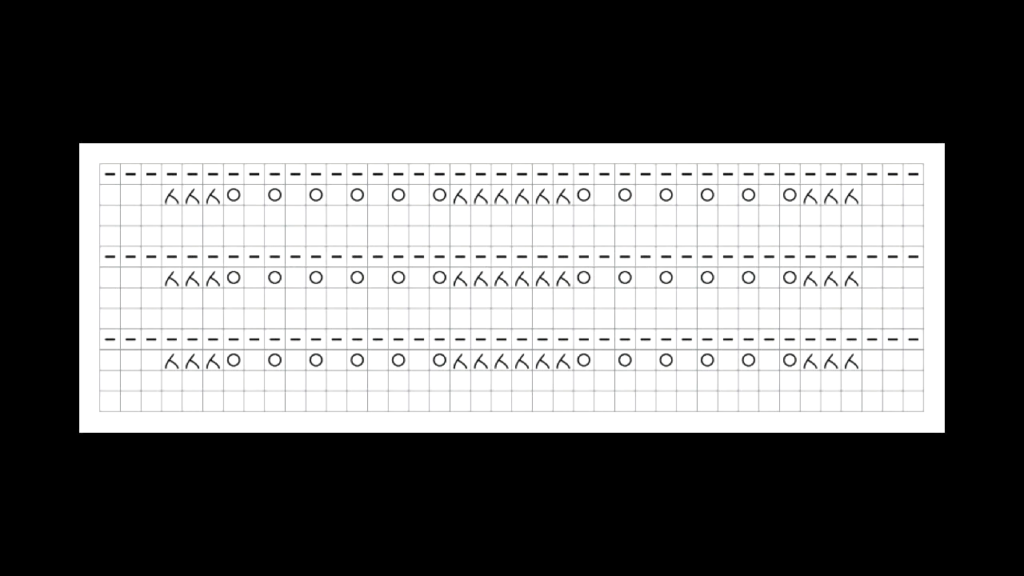

Now in knitting you really see this use with very complicated lace and cable patterns. I started knitting this monster last year. It’s called margen [sp?]. It involves twenty different charts with fifty-six instances of them in use at any given time. Knitters, this is row one:

Each one of those letters corresponds to a different chart, which vary in length from two rows long to sixty-six. You could even look at this is a type of interleaved multithreading (pun very much intended) where the CPU, which in this case is my brain, has to take a new instruction from each coroutine in turn. And depending on how much RAM I have available, things can grind to a halt. This is not the type of pattern you knit at the pub.

So I’m going to switch a little bit now and talk about pattern languages and how they relate to programming languages in general. So in case you didn’t know there’s no single worldwide knitting authority. Everybody writes their patterns differently. There’s multiple competing standards. That’s kind of another way it’s like programming.

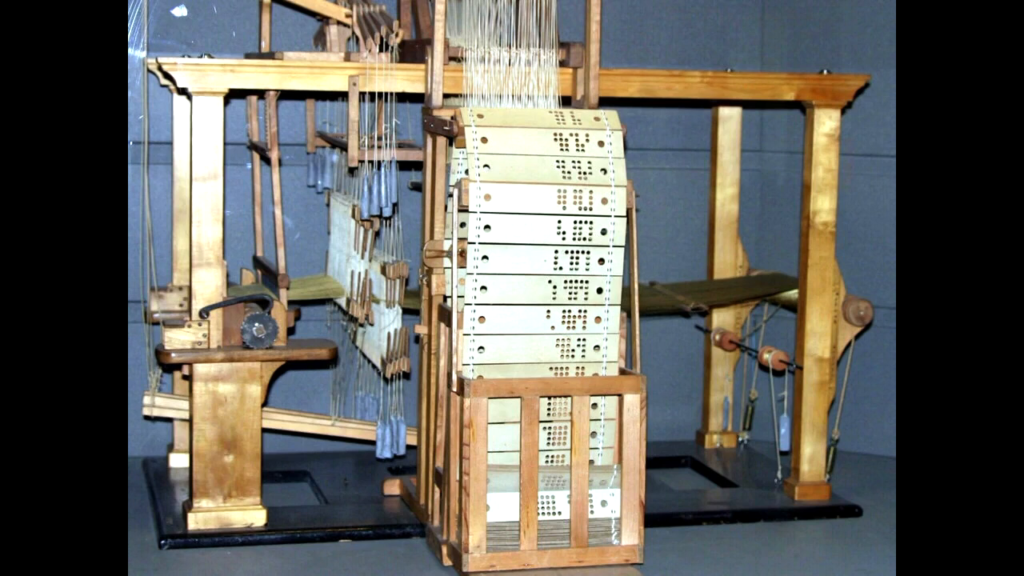

So the mind-blowing thing is that the history of programming languages actually begins with textiles. And I know some of you are probably familiar with this. What is this?

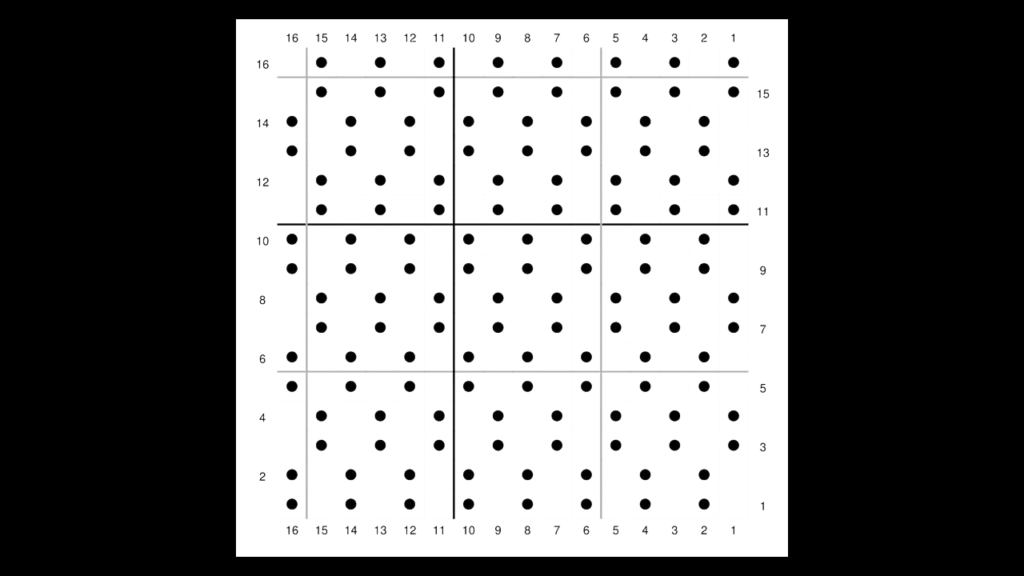

This is a jacquard loom, invented in 1798 by Joseph Marie Jacquard. And what is on the front of it? Punch cards. Jacquard developed this forty years before Babbage wrote of using it for the Analytical Engine. So have a look at those punch cards, and then look at this modern knitting stitch chart.

Pretty similar. So when executed this pattern creates a stitch called “moss stitch.” The blank squares are a knit stitch and the dots are purls. This is effectively binary. This is knitter’s machine code, you know. First-generation programming language. There’s no compiler or assembler needed. It’s super easy for the CPU—remember, my poor brain—to execute this. I see a blank, I knit. I see a dot, I purl.

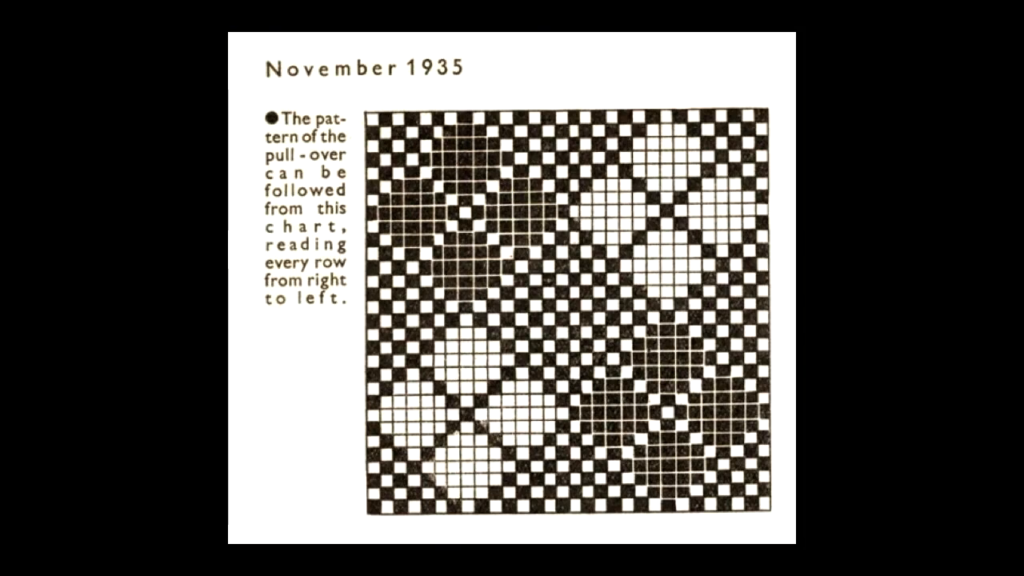

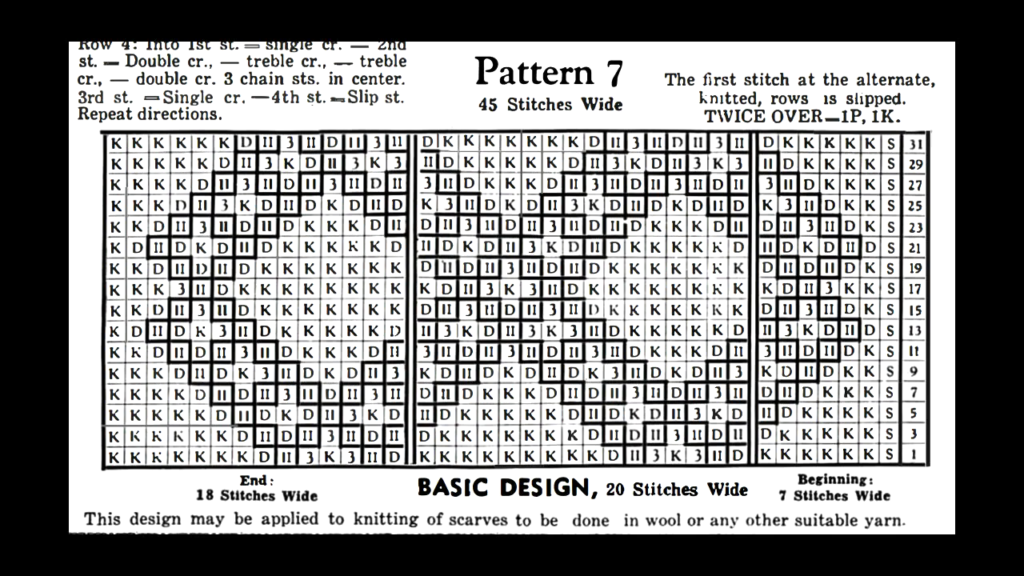

This is another example from 1935, a checkerboard design. Instead of using symbols this uses colors, because this is actually a multicolor design. And charts like this are great for that because it provides a form of error-checking. I can TDD by holding my knitting up at any time and makin’ sure it looks like what it’s supposed to look like.

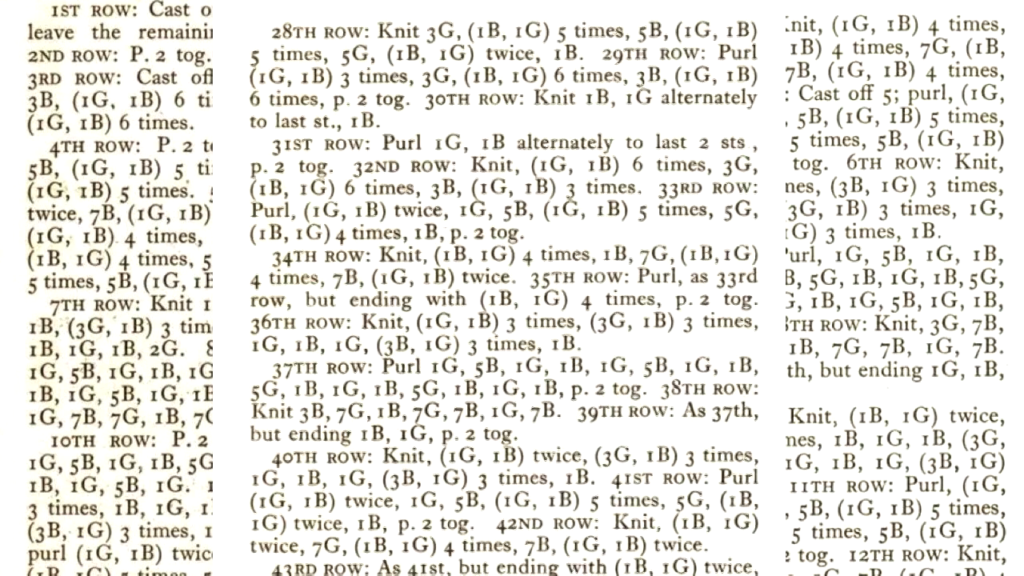

It’s also data compression. It saves a lot of space. So if this series of steps were written out in words it would take up a lot of paper and ink. And I know that because this particular pattern includes it: pages, and pages, and pages.

So as patterns got more complicated publishers realized they could save space in this way. And they could provide even more information by adding more symbols in.

So this example’s from the 50s and it uses five different typographic symbols to represent different instructions, to get an additional level of abstraction here. This is a second-generation programming language. It’s like assembly for knitters. You know, I could read it but to actually knit it I have to translate those symbols into the appropriate actions. And since these particular symbols aren’t widely-used, it’s not very portable. Like I’m sure the other knitters in the room are going, “Roman numeral 2, what the hell is that?” Like, it’s hard. And so it’s also no longer a one-to-one match with the output. I can’t easily hold my knitting up and make sure it looks right. I know there’s dark lines on there but without those it’d be really hard to do error-checking.

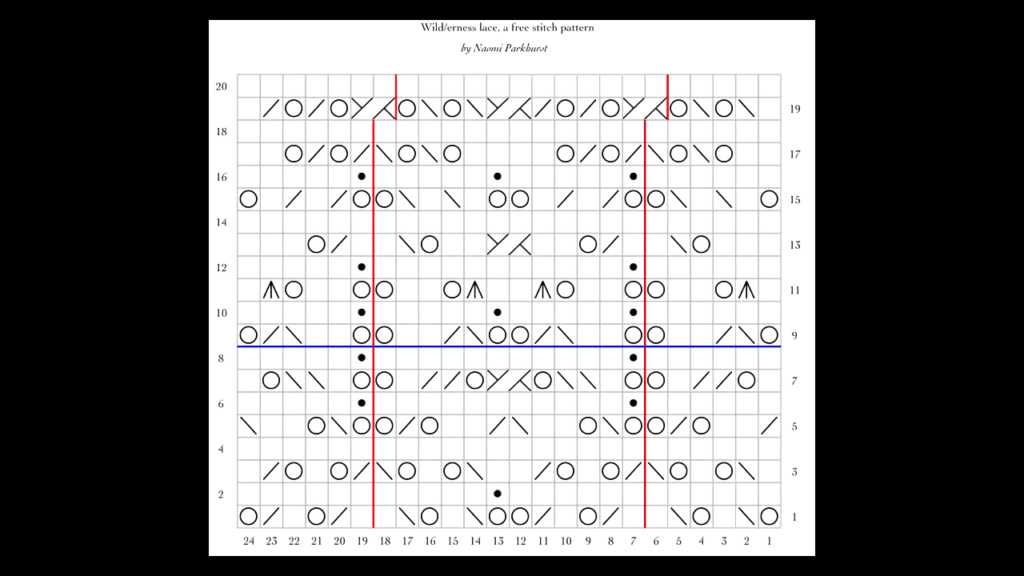

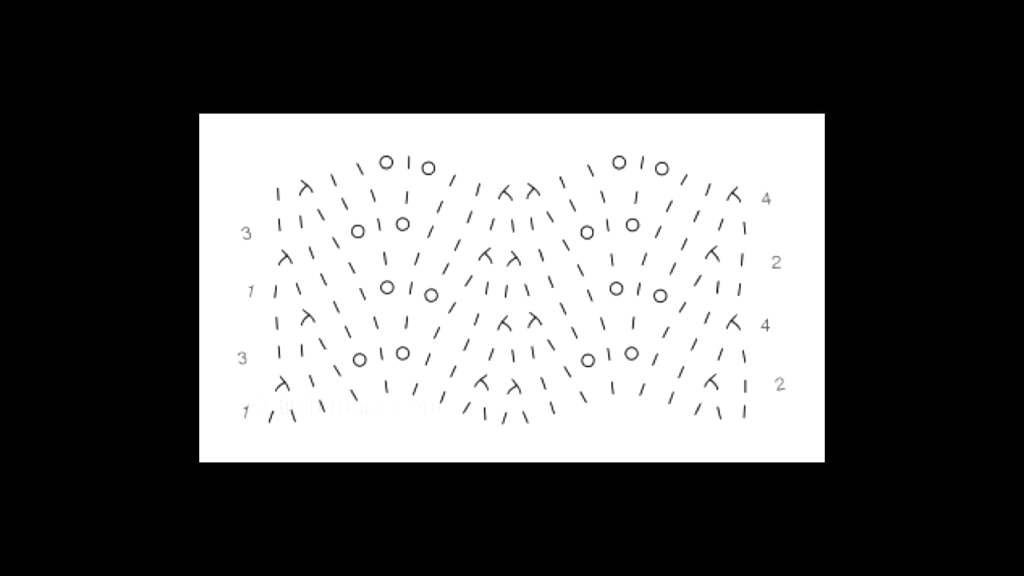

So modern knitting charts like this one try to balance abstraction and portability with faithfulness to the output. We still don’t have a worldwide-agreed standard but we’re gettin’ there, so the symbols are pretty widely used. And they look like what they’re representing. Like the circles are for yarn overs, which make holes. Forward and backwards slashes represent decreases, because they lean to the left or the right. A centered three-to-one decrease is that sort of bird foot-lookin’ thing. So it contains a lot more information. Like between the symbols and the colored lines you get like nine pieces of information in a very compact little space. Looks good.

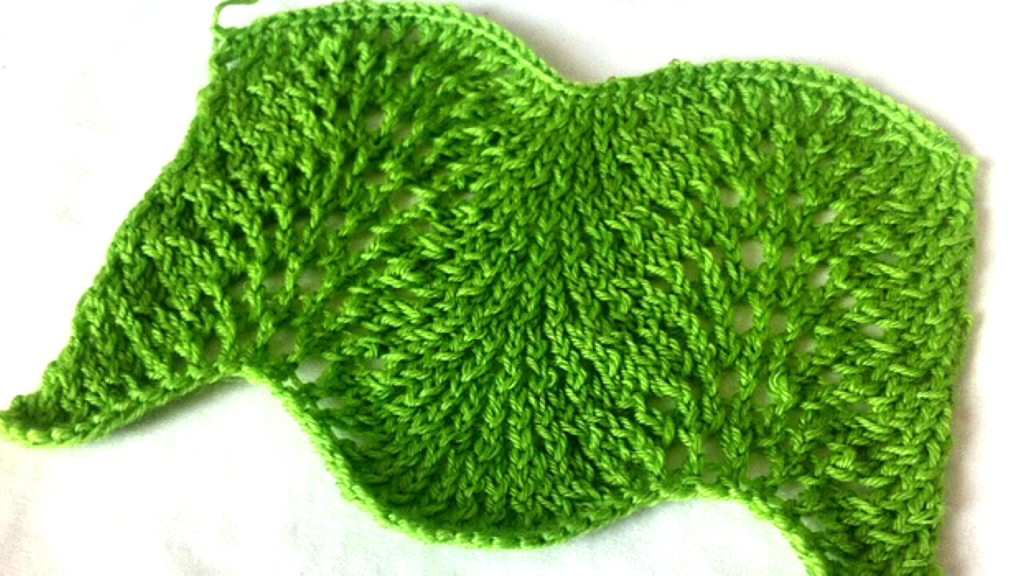

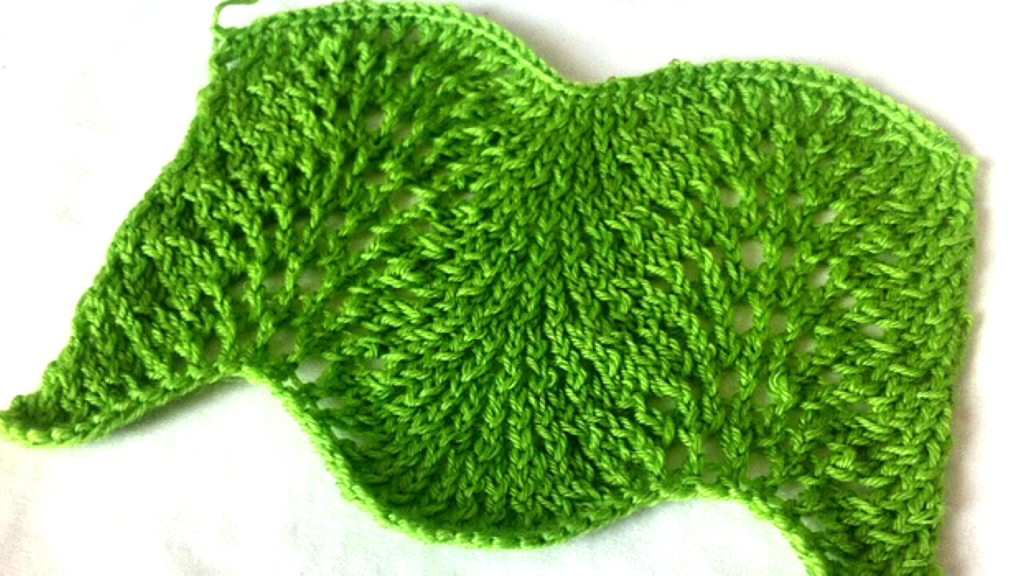

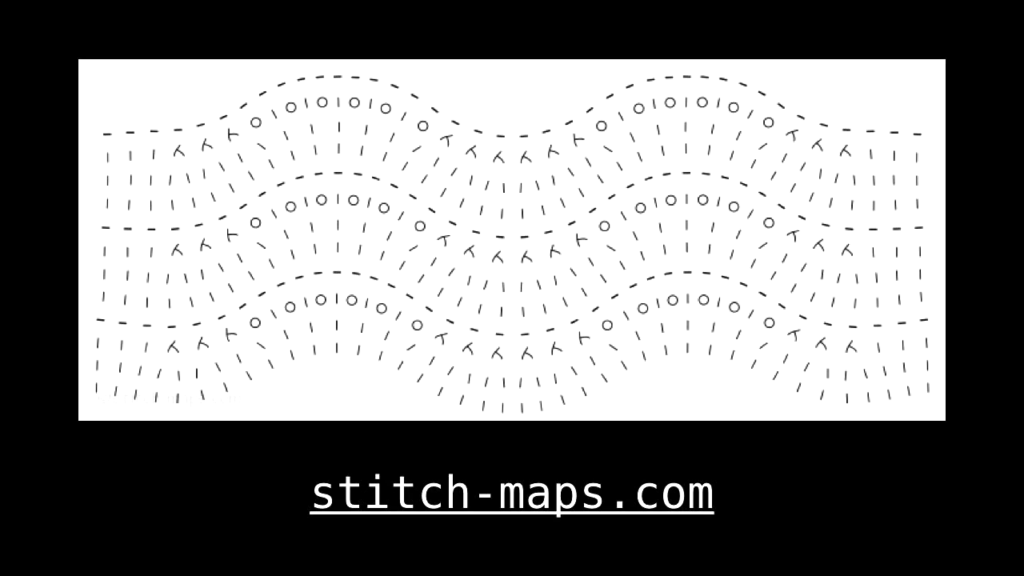

But some knitters think this can be taken further. The problem they say is that grid. So remember this from my intro. This is called feather and fan stitch. And you see it kind of undulates up and down really nicely. But you don’t get that in an orthogonal grid, you know. You get this:

Which is concise and readable and all those good things…but doesn’t look like the end product. So a new syntax has proposed called Stitch Maps. It’s basically the fourth generation of knitting pattern languages, knitting charts. And it looks like this:

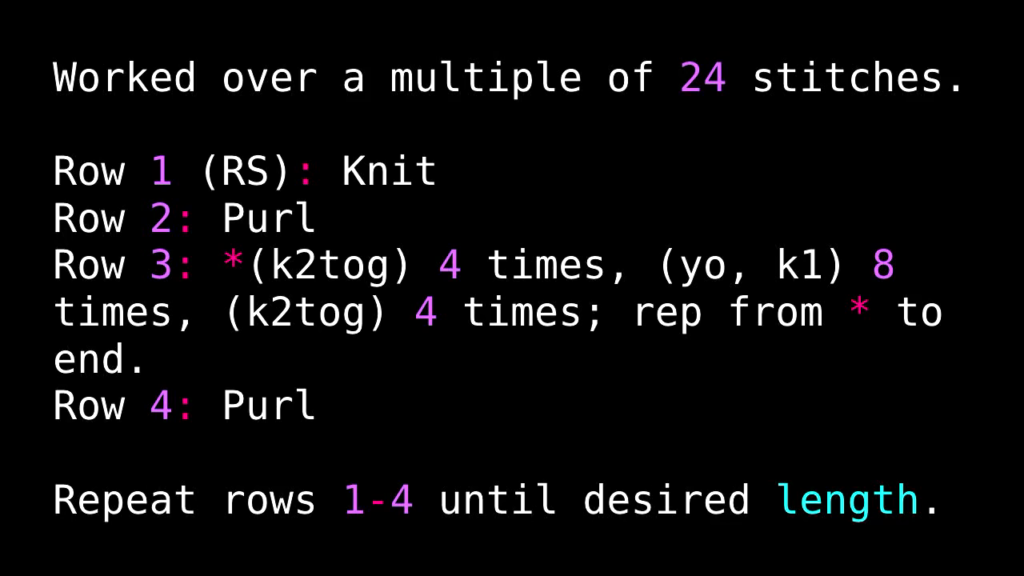

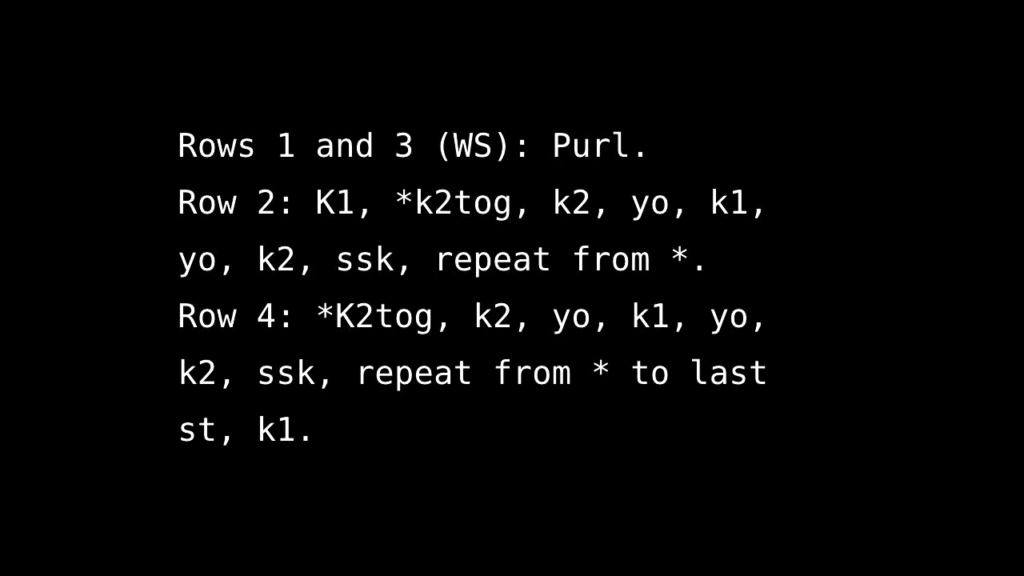

And the idea’s that stitch maps let you see how parts of a stitch pattern fit together. So not just the sequence along a given row, but how they interact row to row, or clock cycles if you like. And the really cool thing is that stitch maps are compiled from a domain-specific language called knitspeak. So you can actually go to the Stitch Maps web site there, and enter a stitch pattern like this:

This is knitspeak, it looks just like a normal knitting pattern. And it will compile that and turn it into a visualization that looks like this:

So this is pretty much state of the art when it comes to knitting charts.

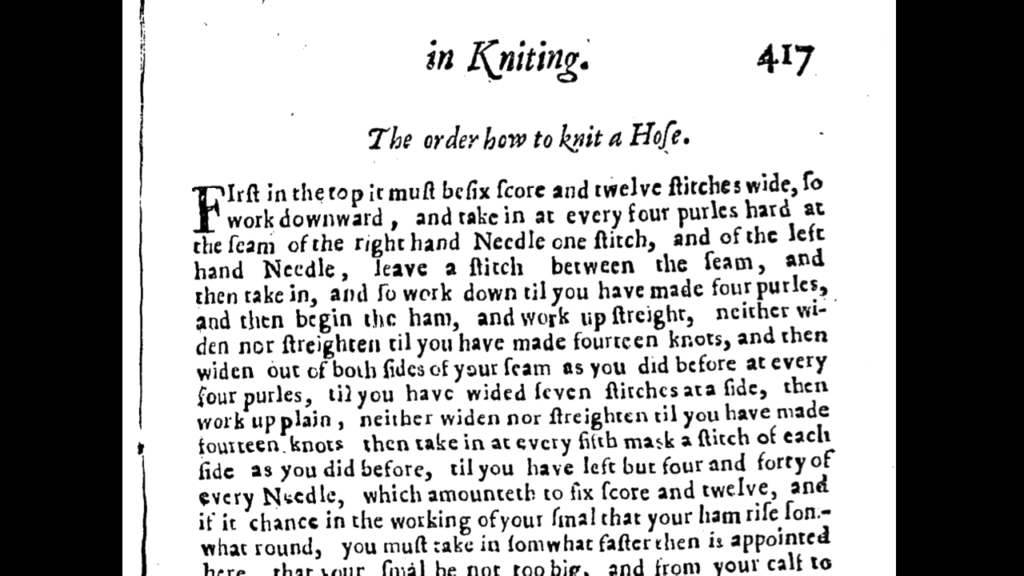

But what about text patterns? So they’ve evolved quite a bit, too. So the first text pattern I can find in the English language was published in 1655. This is what it looks like, “The order how to knit a Hose:”

Which is basically how to knit a sock. So I know it looks impenetrable, but if you’re a knitter you can kinda, sorta start translating it, it makes a little bit of sense. But the UX is terrible. It’s long and vague and hard to follow.

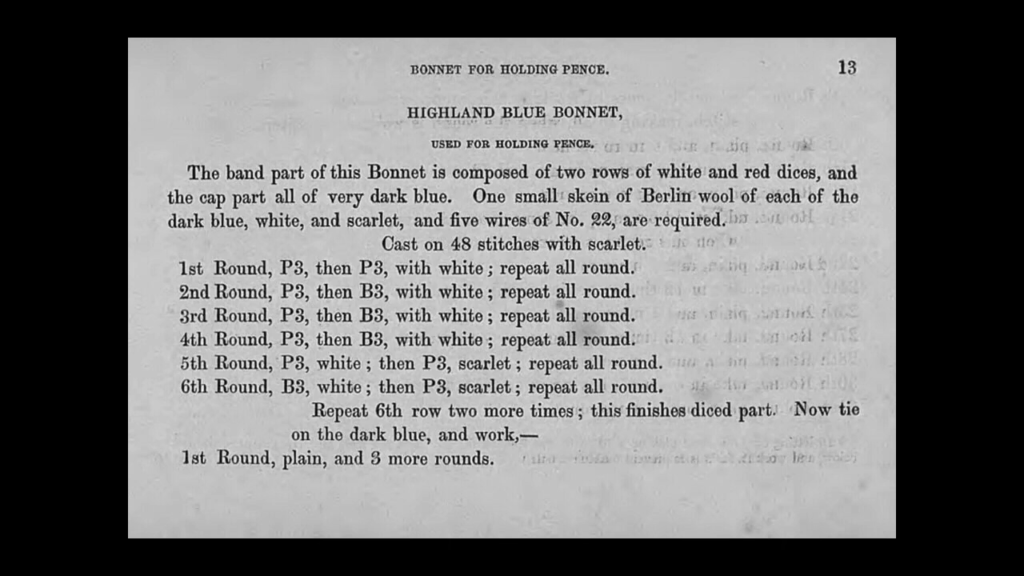

So 200 years later, we’re gettin’ there. This is 1846. It’s a lot more readable, you know. The cast on row’s clearly marked. We’re using some abbreviations to make things more concise. That’s all good. But what’s not great is you know, we’ve still got whitespace and indenting all over the place. And the abbreviations aren’t just not-intuitive, they’re misleading. The P3 here? P doesn’t stand for purl. It stands for plain stitch, which nowadays we call knit. And the B stands for backstitch, which is purl. So it’s exactly reversed. This is like the whole big-endian/little-endian thing. Like, if I give this chart to another knitter and they don’t know the intended schema, they get the exact reversed output.

So this is a modern knitting pattern, analogous to a third-generation programming language. So, clear and easy to follow, standard abbreviations, broken down into modules, you can swap ’em in and out. User experience is pretty good but…those switch statements. I just hate them. And there are so many of them. So again, some knitters think we can do better.

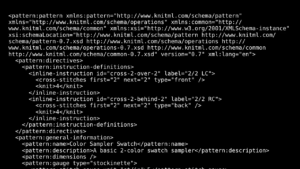

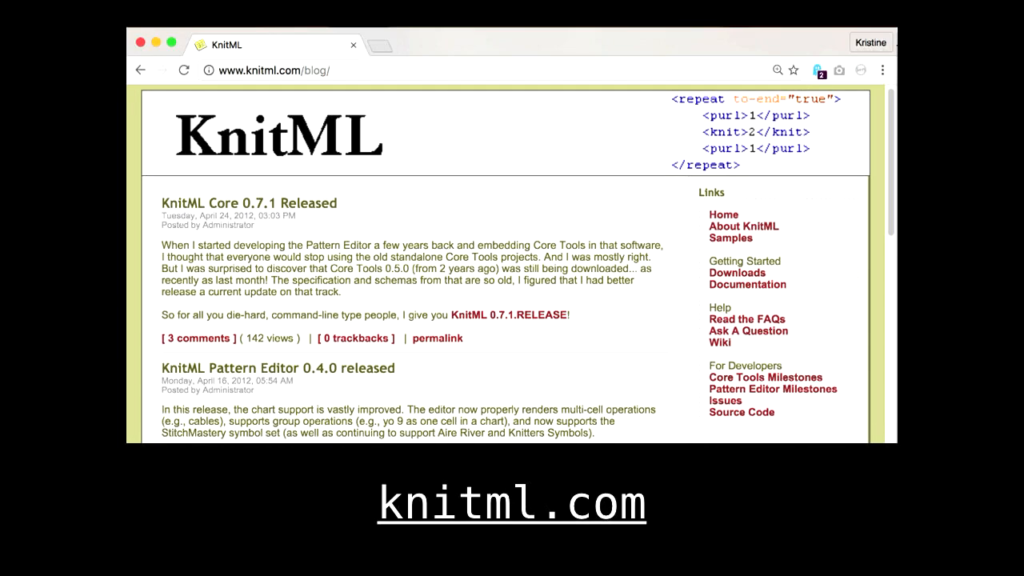

Enter KnitML. KnitML is an open source project with a goal to promote a new international standard, an intermediate format for knitting pattern expression. Knitting patterns are algorithms. And by formalizing a standard in this way, we can allow computers to make decisions about them. And that allows for all sorts of useful operations. I could download a pattern with just my size selected. I could have it in English or French or German. I could use charts or words, whichever I prefer. I could even use the abbreviations I like. It could even compute out those occasionally mathematically-complex things like “increase 17 stitches evenly over 113,” you know.

And it would have advantages for designers too, because they could write a pattern in the way that makes sense to them, knowing that their audience could download it in the way they prefer. And more crucially, they could use tests and validation to check for errors. So many knitting patterns have errors. And they could even use a visualizer to preview the output.

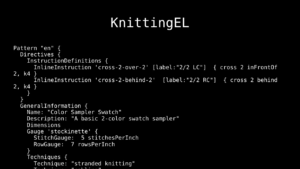

So this is what KnitML looks like. And…it’s not particularly compact. And it doesn’t look like a traditional knitting pattern. But remember this is just for computers to use; it’s an intermediate format. It’s not expected that humans would ever directly manipulate this. Instead the project provides a tool called KnittingEL, which is Knitting Expression Language, and this is how the designers express their pattern. And it sort of looks like a published knitting pattern.

But the project provides Java-based software to convert KnittingEL patterns to KnitML which can then be passed on to supporting software, as I mentioned, like validators, renderers, and visualizers.

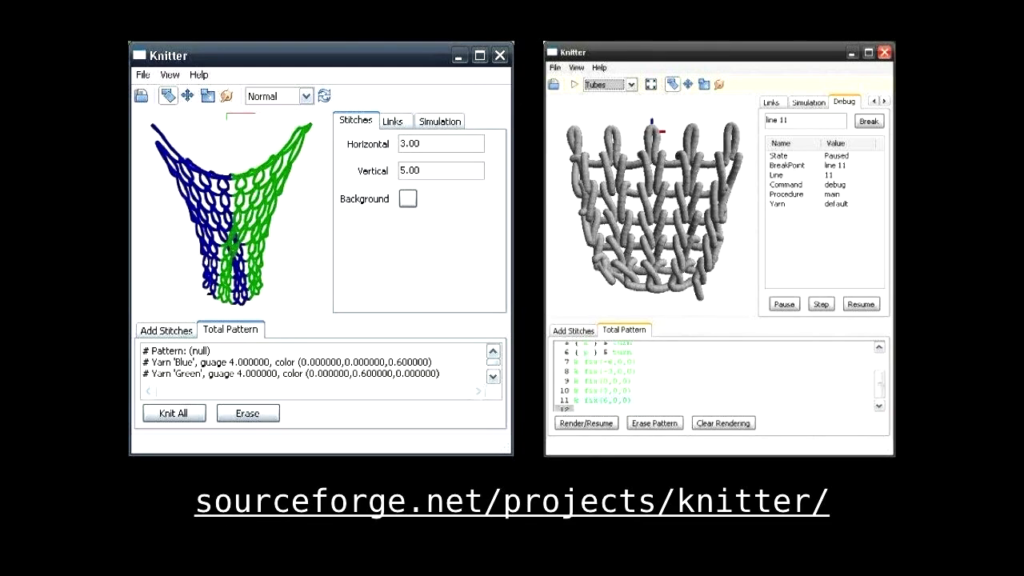

So here’s one for example. This is an open source visualizer called Knitter that processes a KnitML pattern and produces a three-dimensional model of the resulting knitted fabric. And you can even stretch it and see how it responds.

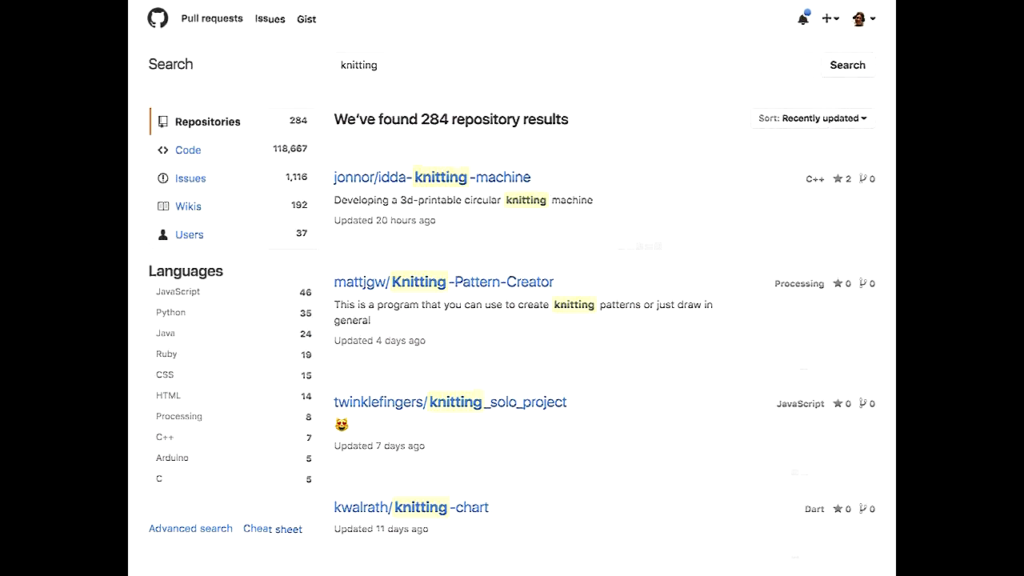

This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to open source knitting. Like if you go to Github tonight and look—and this screenshot is old, there’s probably more. Hundreds of repos to play with. You know, Go language implementations of knitting pattern parsers. You’ve got custom row counters for your smartwatch. Apps for JPEGs into knitting charts. The source code for knitting ipsum generator for your next web site. Instructions for wiring your own row counter which only slightly looks like a bomb.

A knitted and felted bag—this is a cool one—with a sewn-in Arduino where you actually upload your knitting pattern, press the button, and it lights up LEDs in patterns to indicate the next stitches that you’re meant to knit.

Here’s one I myself designed and knitted, a beanie for Camp JS (Oh, I have it.) that uses a Gemma microcontroller, six LEDs, and a coin cell battery to make myself visible up on the misty mountain. Is it lighting up? Oh no, maybe my— I’ll power it up later. Battery’s come undone.

Sweaterify is fun. This is a tool. Lets you upload an image and imagine it into an ugly Christmas sweater, and you can even download it. But more importantly this was built by Mariko Kosaka, who did amazing talk at JSConf last year called Knitting for Javascripters. It’s on YouTube. You should totally watch it. And in it she talked about one of the most popular crossover knitting and programming activities, which is hacking old knitting machines from the 70s and 80s.

So these are very popular. You can pick one up on eBay cheap. Brother made a ton of them. And hacking them usually involves making your own serial cable and using it to upload your own custom designs to the machine. And people are putting these to some very cool and very weird uses.

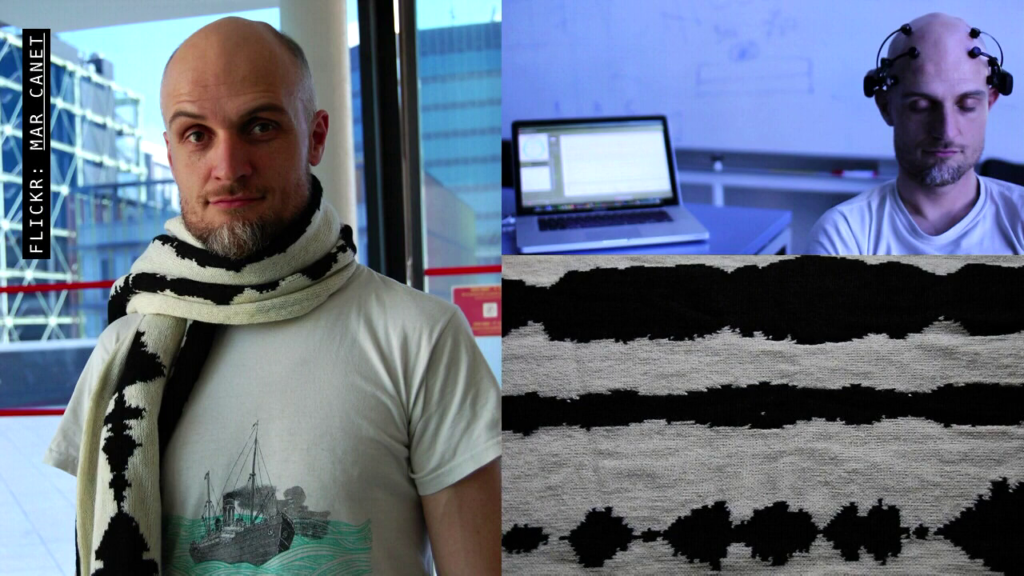

So on the cool side the NeuroKnitting project plotted brainwave activity into a knitted pattern. They used a wearable EEG to record users’ affective states while listening to Bach’s Goldberg Variations, and then knitted that into a scarf on a hacked knitting machine. So that is his brain waves while listening to the music.

Now on the weird side—and warning: nightmare fuel—you’ve got artists like Andrew Salomone and his Machine-Knit Identity-Preserving Bitmap Balaclava. He Photoshopped images of his own head from every angle into a single rectangular bitmap and then knitted it on a hacked knitting machine.

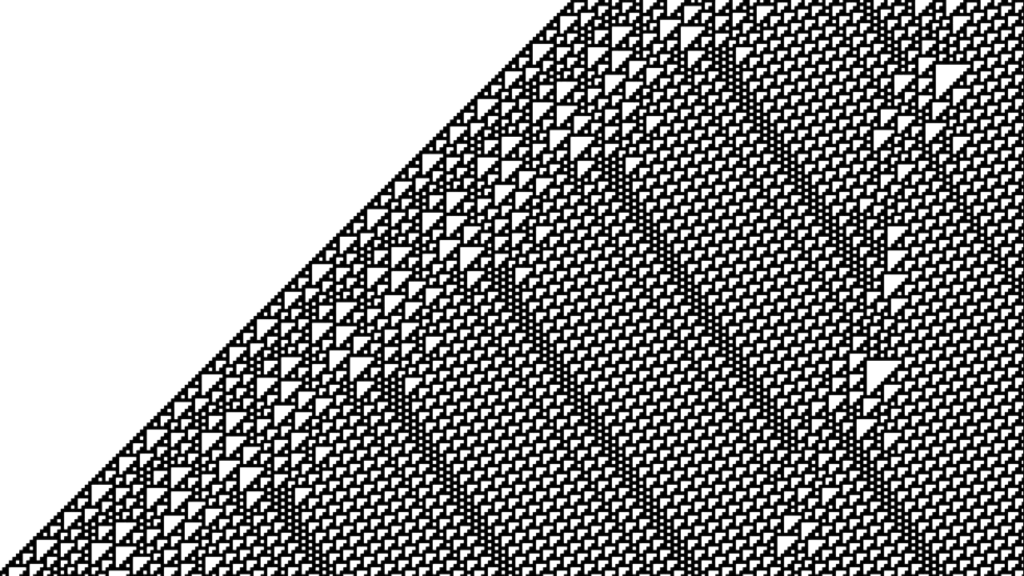

So my favorite knitting tech project recently is KnitYak. You guys might’ve seen it on Kickstarter. So Fabienne Serriere, fbz on Twitter, she’s using a hacked industrial knitting machine in a shipping container in Portland (because of course) to knit provably-unique scarves using elementary cellular automata. So as a backer I get to choose my own colors, rule, and starting row. And the rule determines how each subsequent row changes depending on the stitches that are encountered.

So this is where things get really interesting. Because one of the rules that I can select is Rule 110. And as some of you may know, around the year 2000 Matthew Cooke published a proof that Rule 110 is Turing complete and is capable of universal computation. And it can be knitted. So given an infinitely-long ball of wool, I can simulate any Turing machine and by extension the computational aspects of any possible real-world computer. Which is pretty mind-blowing.

And that’s me. Thank you very much.