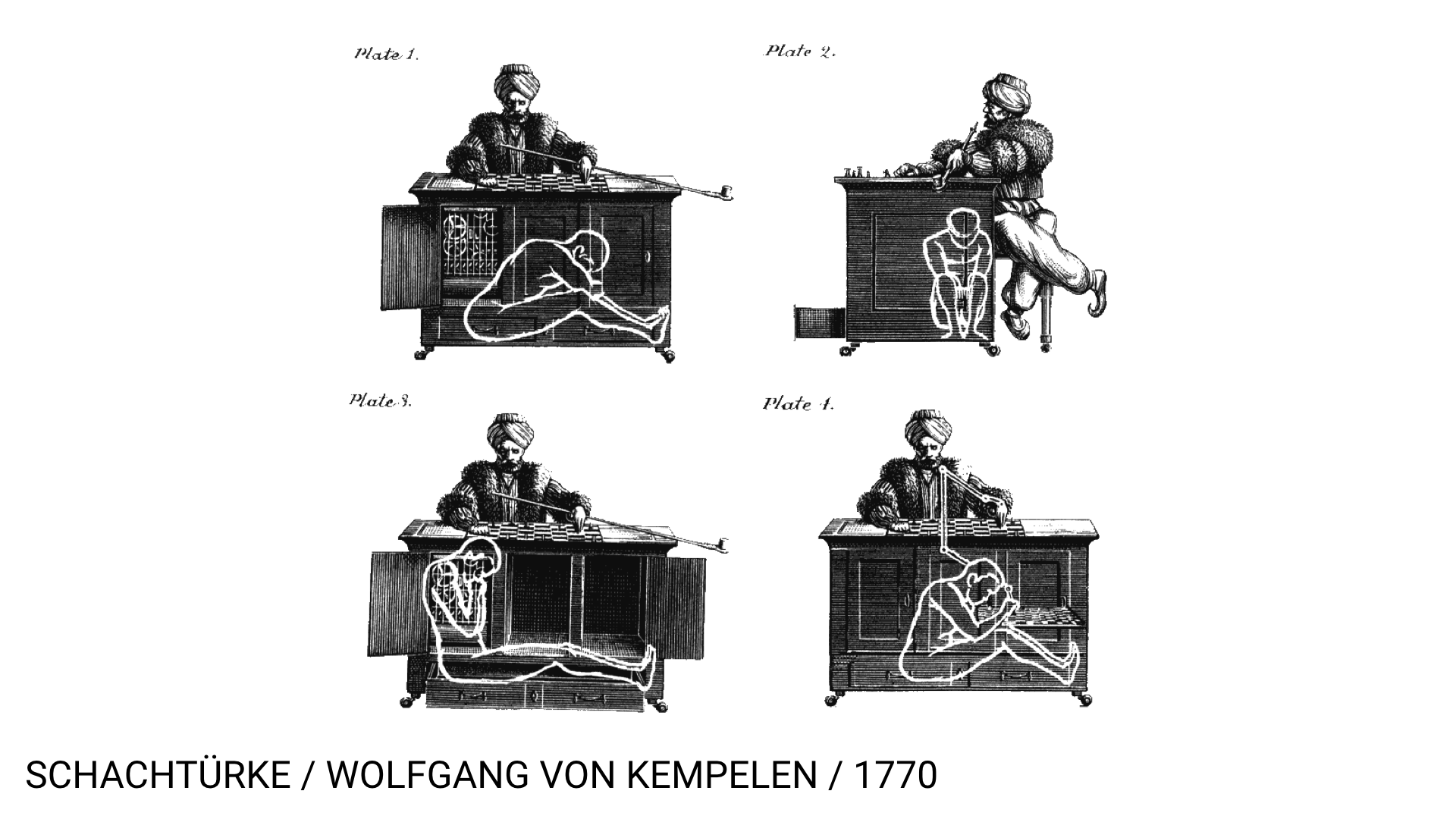

Right. So, this is the Mechanical Turk. It’s a tech conference, so I’m showing a picture of the Mechanical Turk. More contemporaneously known as The Turk, The Chess Turk, Kempelen’s Turk, or the Automaton, it was an apparently autonomous chess-playing robot build by Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1770. For the best part of sixty or seventy years, it entranced the nobility of Europe. If you had a social calendar in the late 18th century, this was the bomb.

And the reason why it was so popular, the reason why it was so incredible is that nobody could figure out how it worked. It was either an absolute technological marvel far surpassing anything seen to that point, or it was magic. It was possessed, in one story, by the ghost of a Prussian mercenary who was amputated. Of course today we know that the Turk worked by means of a small chess player hidden inside it an moving compartments that could cunningly hide that person.

In 1804, Kempelen died and the Turk was purchased by a Bavarian musician called Johann Mälzel. At this stage, the Turk was in a pretty bad condition, having spent thirty-five years touring Europe, and Mälzel spent some time learning its secrets and touching it up and restoring it, and put it on permanent exhibition in London. And this is where it gets interesting.

In 1836, a young assistant editor from a little-known literary journal called The Southern Literary Review went to go and see the exhibition and wrote his review of it. And he said,

No exhibition of the kind has ever elicited so general attention as the chess player of Mälzel. Wherever seen it has been an object of intense curiosity, to all persons who think. Yet the question of its modus operandi is still undetermined. Nothing has been written on this topic which can be considered as decisive — and accordingly we find everywhere men of mechanical genius, of great general acuteness, and discriminative understanding, who make no scruple in pronouncing the Automaton a pure machine, unconnected with human agency in its movements, and consequently, beyond all comparison, the most astonishing of the inventions of mankind. And such it would undoubtedly be, were they right in their supposition.

Edgar Allan Poe, “Maelzel’s Chess-Player”

This young assistant editor was Edgar Allan Poe, who two years after this essay would publish his first collection of short stories. And it’s actually kind of incredible. It’s really worth reading. He lays out the groundwork for some of the early tropes of science fiction. He establishes what he calls “tales of ratiocination,” what we today call detective stories. And establishes an idea of what he called literary analysis, the use of fiction, the use of stories (in his particular case horror stories) to reveal truths about the world. To show us insight into complex systems and structures.

It’s no coincidence that one of the most significant early pieces of technological criticism we have comes from a horror writer. Poe didn’t write horror to titillate, to shock, to scare. He wrote horror because he knew it was a way of talking about complex things in the world, a way of revealing some truth, a way of guiding readers through a complicated narrative that reveals some truth about ourselves towards the end.

150 years after Poe’s incredible essay, we’re still talking about technology as if it’s magical. In the 1980s, 46% of Time articles dealing with the subject of the personal computer, computational culture, and the people involved in the development of the computer, framed those articles in context of magic and the occult. 46%.

And the reasons for this are complicated. It’s not as simple as saying, “Well, you know, technology’s hard and it’s difficult to explain so they use magic as a metaphor.” It’s about cultural appropriation. The 1980s was a time of great social change, the end of the Cold War, so shifting social and cultural structures all around the world. And out of what had previously been the realm of experts and a weird subculture came this thing called the personal computer, and people had to figure out a way of dealing with that. And the best way of dealing with that was to assimilate it using a language that people were already familiar with, the language of magic and the occult. Because we need these complex systems explained. We need them structured for us in order that we can actually bring them into our lives.

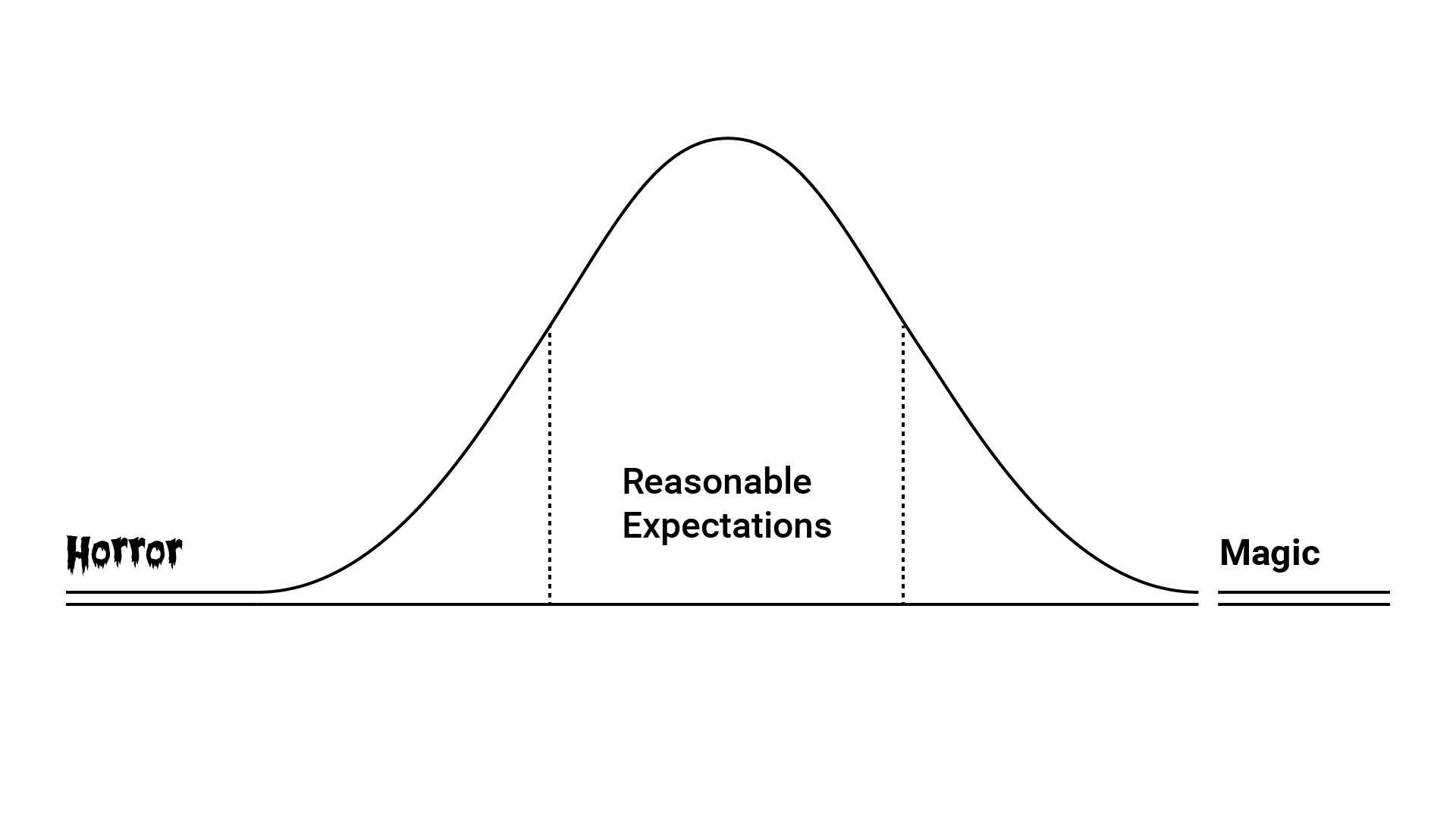

And of course when magic goes wrong, the narrative of magic can quickly turn to horror. If you’ve build a tacit narrative that suggests that all technology is somehow magical, then when it goes wrong of course it becomes horrifying. We kind of construct, internally, a bell curve of what we reasonably expect technology to do. So what we can expect a certain technology, particularly autonomous technologies and computational technologies to do, and then we structure ourselves within that. So for instance if you took Facebook, the middle of this bell curve might be your daily Facebook use, a couple of likes, sharing a GIF, spying on your ex, that kind of stuff.

Towards the top end, you’d have quite joyous experiences, perhaps. So, that said ex sending you a private message inviting you to go for a drink, accompanied by feelings of joy and perhaps slight inadequacy.

Towards the lower end, you’d have things like someone breaking into your Facebook account to take your personal details to get into your Amazon account to convince your credit card company that they’re you and steal all your money. Not so joyous. Bit horrible, really.

But still within the framework of reasonable expectations, because we’ve heard about these stories. We know how that system works well enough to be able to balance those risks and benefits.

Outside of that, you then have reasonable things that are unexpected. And I use “reasonable” in the sense of rational. It’s rationalizable. And that might be for instance Apple last week deciding to brick everyone’s iPhone who’d had it repaired. Totally reasonable. It was rationalizable. It’s not magic. But it was unexpected. And it kind of changed those boundaries.

Beyond that, at the far end, you have horror and magic. Horror, the unimaginable. Worse than the most dreaded possibility. And at the other end magic, the impossible. The physically impossible. And magic is the thing that technology angles towards. We angle to achieve magical things, but often end up with horror.

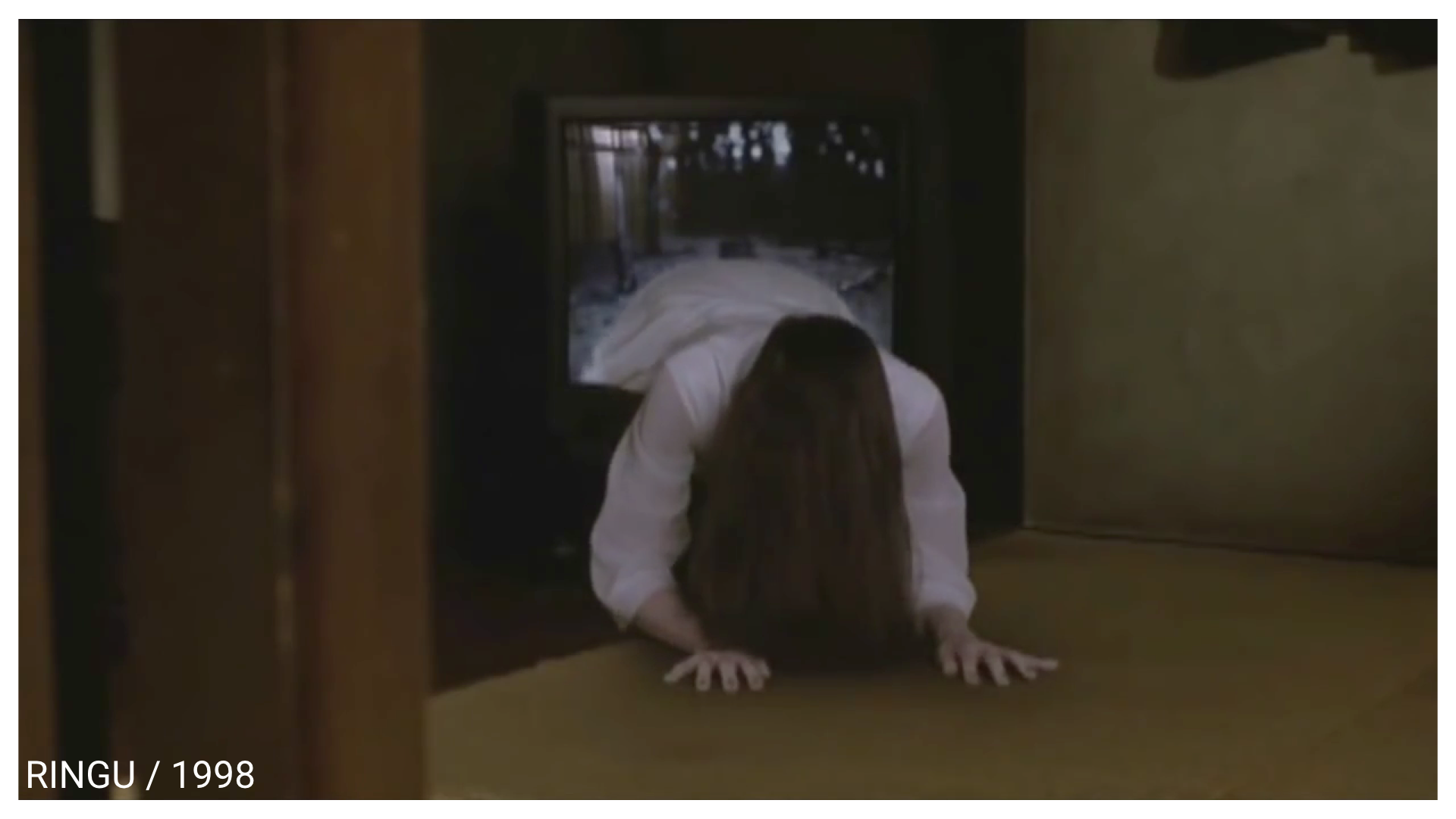

A great example of how these expectations work and what happens when they go wrong is the 1998 Japanese supernatural horror film Ringu. The horror of Ringu worked because we built a set of expectations about how a TV, a video player, and a tape should work. Worst case scenario, video player chews up tape, small house fire. Not vengeful spirit of murdered teenage girl climbing out of television to devour your soul. The horror of Ringu is in that collapsed expectation. The sense of uncertainty and instability that’s suddenly introduced to both the viewers and the victims.

And in a theoretical sense there’s really no difference between the vengeful spirit of a murdered teenage girl crawling out of the television to devour your soul and cats trying to catch mice on an iPad. To the cats, much like the girl in Ringu, the world of the screen and the physical world are one continuous reality. Why shouldn’t the mice come out the side of the iPad? They don’t have a framework for what the reasonable expectations of the behavior of that technology are. And in a sense, the cats are kind of angled to the other end of that bell curve. They’re going for magic. They’re going for an iPad that can produce mice from nowhere.

Sorry. On with the show.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zaO_H2cUh60

This is an incredibly important piece of footage. It’s got a French name that I’m not even going to try and pronounce, but in English it’s often called “The Arrival of the Mail Train.” It’s a fifty second film that was made in 1895 by the Lumière brothers, and it’s very significant for being one of the first pieces of moving image that was shown to large public audiences, one of the first pieces of moving image to go into what would become cinemas.

And it’s accompanied by an urban myth that we often hear. There’s a couple of indications that myth might be true. But the urban myth says that upon seeing it, people fled the cinema. They saw this train rushing towards them, and they ran out the cinema screaming. You see, people had experience of trains (Trains are big heavy metal things that destroy things that get in their path.) but didn’t have experience of moving image. They hadn’t yet built a series of expectations about what they might expect moving image to do, and so they ran. They ran in fear, in terror.

This is a video that came out last year that is very similarly framed, interestingly, but features some Colombian guys testing out and showing off the automatic stopping capabilities of their new Volvo. Guess where this is going.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8nnhUCtcO8

With predictable results, right? If there’s a sliding scale at one end of which is Europeans running out of cinemas in the late 19th century, and the other one is cats with iPads, this is firmly in cats with iPads territory. This is up there. Roughly a hundred years of education that says “if a car is accelerating towards you, get out of the way” have just gone. Gone. Because of a software gimmick. The instability this creates is incredible. That’s why we have so many discussions about autonomous vehicles and things like that.

Volvo later issued a statement saying the reason this happened was because the car did not have the pedestrian detection software package, which is optional. It’s 2015 and pedestrian detection is an optional add-on? No, that should be built into the firmware of the thing.

So these kind of collapses of reality and expectation are starting to happen more and more. And this becomes incredibly worrying when we talk about these technologies being brought into the home. Because the home is a thing you need to survive as a biological animal. It gives you shelter and heat and food and light and water and things like that. And now suddenly these incredibly fallible, destabilizing objects are coming into that environment. The smart fridge is the golden fleece of the Internet of Things, that sort of thing that everyone’s been aiming for since the 1970s but never seems to get near to. And you can imagine what might happen if a smart fridge suddenly starts behaving [inaudible; following video starts playing].

Suddenly we end up with a world of haunted houses, where fridges are malfunctioning because of firmware failures or whatever. And the haunted house is a really well-established part of the horror genre. One of my favorite haunted house films is the original House on Haunted Hill, and also the remake, which is pretty good. But the thing about House on Haunted Hill is that it’s not a supernatural thriller. It doesn’t have any supernatural ghosts or anything in it. What happens in House on Haunted Hill is that Vincent Price uses the supernatural, manufactures a haunted house, in order to kill his wife and her lover. So he uses this building of this air of spirituality and hauntedness in order to perform a simple, everyday murder. Not everyday, hopefully. You know.

But that’s quite a common tactic, to create a visage of something going on that really isn’t going on, and you as the viewer don’t even find out till near the end that’s the truth. Alfred Gell, who’s an incredible technology writer, would call this a technology of enchantment, which he defines as,

technical strategies that exploit innate or derived psychological biases so as to enchant the other person and cause him or her to perceive social reality in a way that is favorable to the social interest of the enchanter.

Alfred Gell, “Technology and Magic”

That’s a long way of saying that basically a technology of enchantment is anything that deceives you, anything that creates a fiction or a sense of reality that simply isn’t true. And you can think here of everything from advertising to the problem of the filter bubble on the Internet.

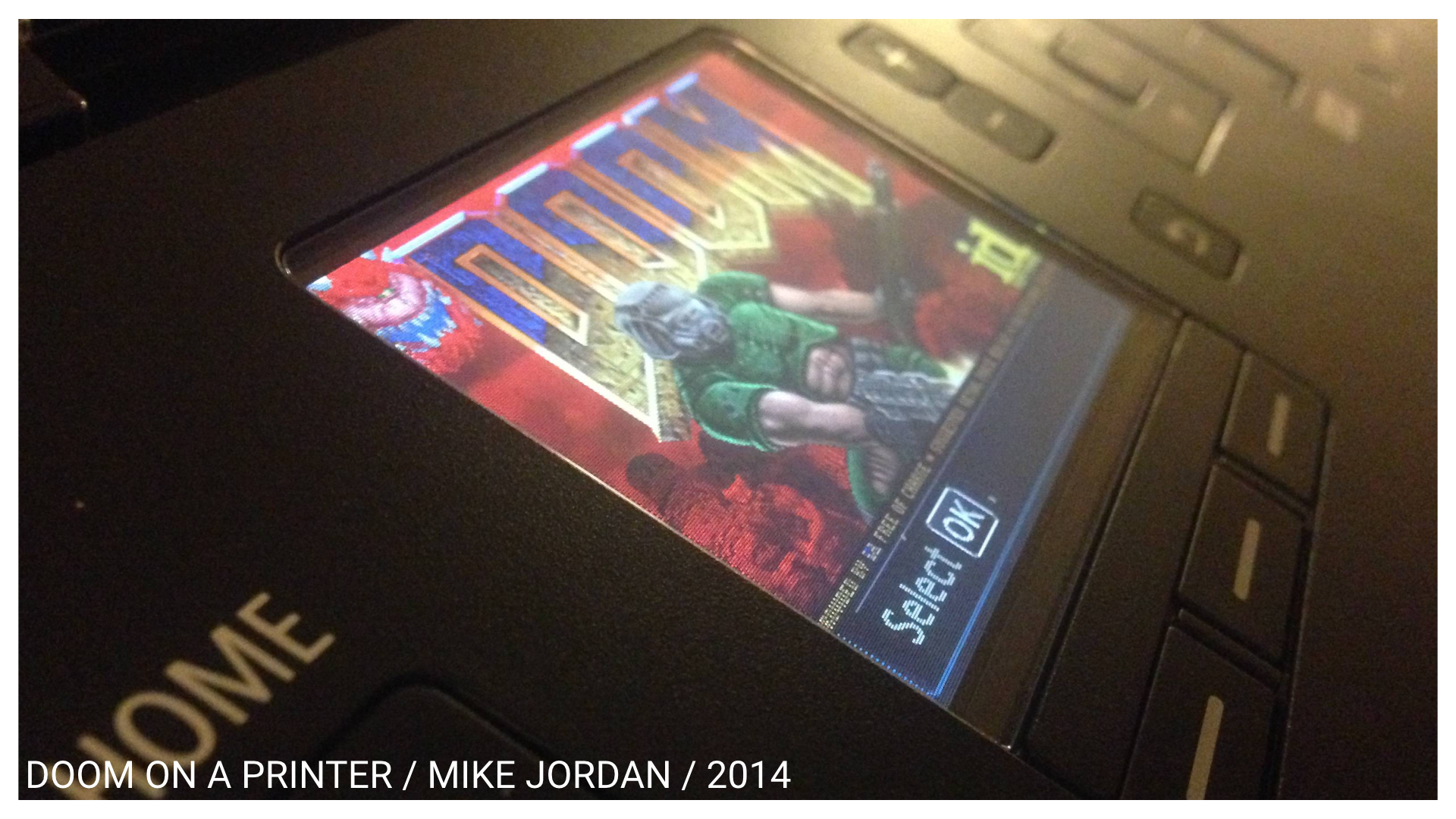

So how does this start to look when it’s moved into the house? This, two years ago, was kind of an interesting example of where some security experts managed to hack a printer over WiFi and replace the firmware with the video game Doom. It’s a fun trick and it was kind of nice, but it exposes the structural problems of these kinds of devices. Any device can be hacked in this way, anything. And if you’re putting things on it that you need to live, things that you need to eat, things that supply you with heat and water and things like that, then that’s really problematic.

Nest has been repeatedly hacked, several times. It’s been shown to be very easy to hack. It’s also, more sinisterly perhaps, been used a lot in DDoS attacks. We know that they get used as nodes when attacking other people. So your Nest might not be haunting you, but it might be haunting someone else.

And it doesn’t necessarily have to be a malevolent action in order to haunt someone. Sometimes just simply ill-considered, badly-designed stuff can be really haunting. Samsung last year released a smart TV. The smart thing about the TV is that it’s voice-controlled. Digging through the privacy policy, some researchers found that it said,

Samsung may collect and your device may capture voice commands and associated texts so that we can provide you with Voice Recognition features and evaluate and improve the features.

Samsung Privacy Policy–SmartTV Supplement [later modified]

That’s the old “we’re improving your experience thing.”

Please be aware that if your spoken words include personal or other sensitive information, that information will be among the data captured and transmitted to a third party through your use of Voice Recognition.

Samsung Privacy Policy–SmartTV Supplement [later modified]

That’s Samsung saying to you, “When you’re in your living room, don’t say anything you wouldn’t want anyone else to hear.” In your living room. That’s baffling that that has been designed in. It doesn’t make any sense.

Perhaps more worryingly, this was two weeks ago, Fisher Price’s Smart Toy Bear. I’m not sure why teddy bears need to be connected to the Internet, but there we are. It’s the age we’re in. Fisher Price, it turned that the API they had for these smart bears that would interact with children, was just wide open. Anyone could access it. Anyone could get into that API and find out the name, age, gender, and location of any of the children with these bears. That’s pretty terrible. So there was a brouhaha. Fisher Price apologized and they said they’d rectified the problem. Their method of rectifying the problem was to say in the privacy policy, again very deep,

You acknowledge and agree that any information you send or receive during your use of the site may not be secure and may be intercepted or later acquired by unauthorized parties.

[NB: this is actually from the terms of use of VTech, who had a similar hacking issue around the same time as Fisher Price]

In other words, “you’re responsible for our terrible API.” And there’s a whole thing here about how privacy policies and end user license agreements are often the most overlooked bit of the design and used for establishing the relationship between users and developers in companies and stuff. And because users are the last people who ever look at those things, it’s often very exploitative.

Smart locks are perhaps the most baffling of all the Internet of Things projects. I don’t know what’s wrong with locks that requires them to now be made connected to the Internet. They were fine in the first place. The August is one of the most notable examples of the smart lock. It’s one of the most widely sold and widely reviewed. It essentially works by detecting when your phone is near through Bluetooth, and then automatically locking or unlocking the door accordingly. Wired when reviewing this (and they get kind of breathless over anything with an LED in) said that it only worked about 80% of the time. That’s not a great stat for something that keeps all your stuff safe, right? That’s pretty terrible.

Beyond that, we know that phones are full of problems and bugs. Bluetooth doesn’t work often. WiFi can collapse. Power… You still have to take your key with you with this thing—that’s the laughable thing—because if your phone runs out of battery, you’ve got to open the lock the old way. Locks are pretty well-designed. They’ve got a real kind of good UX thing with the whole clunk, turn going on. It’s quite healthy, I think. So, smart locks, baffling.

So, two hundred years after Poe’s incredible essay (I really hope everyone reads it) and we’re still talking about technology in terms of magic and the occult. We’re still looking for some magical solution through it. I had before a slide from Nest’s “Magic of Home” advert, but I didn’t want to go too deep on Nest. And that’s fine, that’s fine, that’s how we assimilate complex systems and technologies into our lives. Because we don’t have time to actually critically engage with them on any deep level. So magic is a helpful metaphor.

But we have to be aware that when you create magic or occult things, when they go wrong they become horror. Because we create technologies to soothe our cultural and social anxieties, in a way. We create these things because we’re worried about security, we’re worried about climate change, we’re worried about threat of terrorism. Whatever it is. And these devices provide a kind of stopgap for helping us feel safe or protected or whatever.

But in doing so we run this risk, and all those objects prove this, of unleashing a stream of useless crap on people that isn’t magical, and actually just adds more horror. In the 1980s, Time believed that the personal computer was the magical solution. It would make sense of the world. Suddenly people would have power, magic power. Then it was virtual reality. Then the web. Then search. Then Web 2.0. WiFi. Social networks. Big Data. Augmented reality. The Internet of Things. Open data. Civic tech. Bitcoin.

The people who tell us these things are going to save us are called evangelists. The people who crave them are called fetishists; the belief in some higher power inside of objects. But magic isn’t real. Horror is. No one in this room will ever experience magic because it’s physically impossible. But regrettably, most people will experience horror. The death of a loved one or a violent crime, that happens. That’s a real thing.

The Wired writer, writing about his experience with the smart lock, found one day when he got home that his house was wide open. The smart lock had malfunctioned and just opened. Couldn’t figure out why. Turned out later it was incompatible with another app. Again, not a problem keys have. And he said something quite harrowing. He said,

I haven’t been able to get to sleep without securing the chain since then. I get freaked out at the prospect of someone walking through my unlocked door and standing over my wife and me while we sleep.

Joe Brown, “Review: August Smart Lock”

His home had become a haunted house. The unimaginable had happened. Horror had struck him. And we can’t design for that. You can’t design for the unimaginable because it would be paradoxically prescient to be able to do so. No one can do that. But being aware that in trying to create magical solutions we unleash the possibility of horror is really important.

Ambrose Bierce is another incredible historical figure (Read his Wikipedia page. Just a madly brilliant guy.) disappeared in 1915, going to fight in the Mexican revolution. He was also a devotee of Poe. He was quite famous for writing a thing called The Devil’s Dictionary, which is a satirical dictionary. But he also wrote a short story that I love called “The Damned Thing.”

In “The Damned Thing,” there’s a small American settlement of eight or nine people who are slowly being killed off, and at first they blame each other, they suspect a murderer’s loose. But in the end, they realize that they’re being stalked by an invisible monster. Perhaps the most unimaginable horror, a horror so unimaginable that it’s invisible. And it ends with the main character sort of pleading his sanity to the sky, shouting his benediction. He says,

As with sounds, so with colors. At each end of the solar spectrum the chemist can detect the presence of what are known as “actinic” rays. They represent colors—integral colors in the composition of light—which we are unable to discern. The human eye is an imperfect instrument; its range is but a few octaves of the real “chromatic scale.” I am not mad; there are colors that we can not see.

And, God help me! the Damned Thing is of such a color!

Ambrose Bierce, “The Damned Thing”

Thank you.

Nicolas Nova: Quick question for you. I think someone in the room asked whether you’d be interested in running for mayor of San Francisco. [Tobias laughs] Well…no comment on that.

Tobias Revell: No, no comment. I don’t want to get involved in politics at this early stage in my career.

Nova: My other question was about something you said in the conclusion, “there’s no way to design for that.” But as a designer, how you work is related to that. You can talk a little bit about your speculative design practice, broadly.

Revell: Well, yeah. I work in speculative design, which is in a sense a kind of fuzz testing of design. It’s making really perhaps unexpected outcomes, trying to make the unexpected real in order to test it on people and see how they feel about it. It’s a field of design that fully recognizes that in any development there’s trade-offs. Someone’s going to suffer, something’s going to go wrong. And recognizing that and inviting people to realize that as part of this narrative is really important. It’s fine to say that technology is magic, but it’s also fine to say, well we’ve all seen “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” We know what happened there.

Nova: Thank you.

Revell: Thank you.

Further Reference

Bio page for Tobias and session description at the Lift Conference web site.

Tobias composed a short video setting the Lumière brothers train clip and the car auto-stopping test side by side, showing how both “demonstrate total faith in what the technology claims to be and that it will stop, despite the obvious outcome.”