Vinay Gupta: Do you guys know about John Snow? He’s our local London stacktivist saint.

So 1854, there’s a cholera outbreak in London and people are dropping like flies. This is in the bad days when cholera could really pretty much kill a city. This has happened right in Soho. In fact there’s still a pub called John Snow right in Soho, which I quite often go to drink at sort of as a commemoration of Snow.

Snow takes a map of Soho and he draws a dot in every place where a person died, and pretty soon he’s got what he’s got what he calls a ghost map, and in the middle of ghost map there is the Soho well. So he goes to the well and says, “Right, what’s causing the cholera must be in the water,” he takes the handle off the well, and the epidemic stops. And everybody goes, “Wow. Cholera [inaudible] water. You just stopped an epidemic. You’ve made the invisible visible. Here’s the ghost map. Fantastic.”

The [inaudible] after part, which I only discovered when I was taking a look at this stuff again last night, is that later on they put the handle back on the well. They dig the whole thing up, they clean it up, put the handle back on the well, and the memory that cholera’s caused by dirty water is politically suppressed because it’s such a gross thought that you throw shit in your water supply. And they went right back to doing what they were doing before. Unbelievable.

So this stuff is practical and historical in our context. This is not all stuff that happens in other people’s countries. This actually happened right here 150 years ago, and it was a huge deal.

Photo: Robin Gane-McCalla

Now we’re going to go and really go through the wide picture of this. These things here are called hexayurts, and it’s an open-source building. The nutshell of why this is worthwhile is the wall pieces are full pieces of 4×8, and all the roof pieces are half-sheets. So it’s the simplest way of taking standard industrial materials and mass-producing housing, from these small pods up to these very large buildings. Zero waste, [?] efficient, easy to do, 1,000 units built at Burning Man last year, open hardware, epidemic.

If we were going to try and provide for nine billion people, let’s think about the natural material base. Copper. A billion tons of copper ore, the ore is about 1% metal. Actually, usually .3, .5, but we’ll call it 1%. Take the amount of proven reserve and economically recoverable ore, divide it by the number of people, and it comes out to be a kilogram each, per lifetime. That’s how much copper there is.

Now, as you do higher-priced copper, what’s economically recoverable increases, but we’re still talking on the order of 1, 5, 10 kilograms of copper per human per lifetime. This is a completely new kind of design challenge. There’s no way that you can take the civilization we have and re-scale it for 1–10 kilograms of copper per human per lifetime. You just can’t. You have to think in a completely different way if you’re going to operate inside of this framework where you take the sustainable harvest of the Earth and you divide by nine billion.

You don’t just have to divide by nine billion now, you have to assume that future generations will come, you have to leave the seed corn, you have to leave the standing forests, you have to leave recyclable materials. Otherwise there’s just no way to make it work. It’s design with a completely different constraint. It’s not how you can make it back, it’s how can you continue to make it back for thousands of years, per manufacturer.

So we have to go back to this core question: How do we turn what we have into what we need? And that core question is buried right at the heart of almost every human activity. But all the way through it gets obscured by methods. The core need is covered up by the market, or it’s covered up by socialism, or it’s covered up by environmentalism. But this is what we’re doing. And what makes us the tool-using ape is that we’ve got hands and minds and mouths which allow us a whole additional set of options that we don’t otherwise have, and it’s all around this agenda.

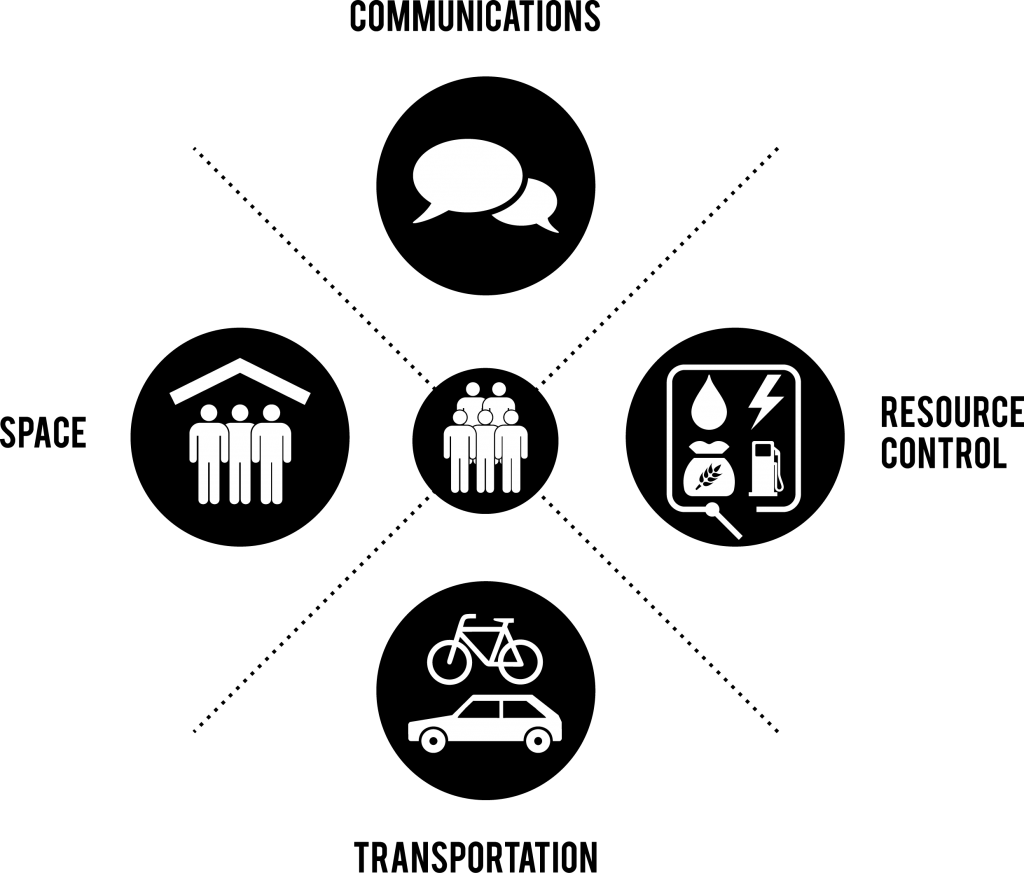

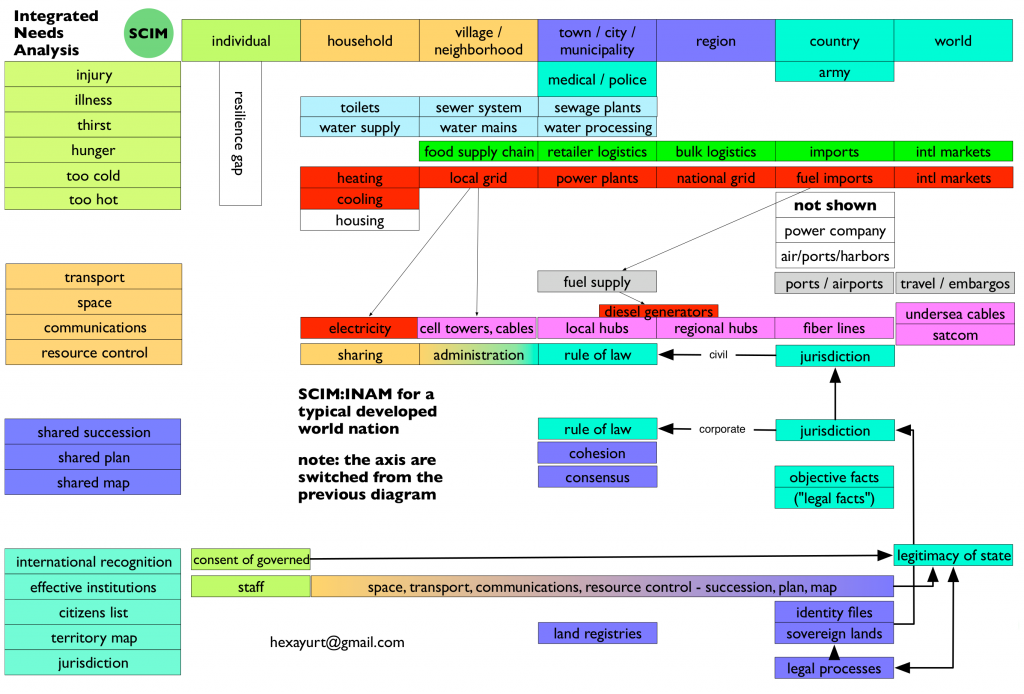

Jay mentioned the Simple Critical Infrastructure Maps stack. Let’s actually break that map out. So, the things you need to stay alive. Shelter. You don’t want to be too hod or too cold; that’s the building we’re in. Supply. You don’t want to be hungry or thirsty; that’s the food supply chain from which you bought your breakfast this morning. It’s the water you see all around you from municipal taps or plastic bottles that came from other places. Illness and injury. If somebody got very ill for some reason, you call 999. If somebody came and tried to kick down the door, we’d call 999. Or we’d just beat the hell out of him. But all of this stuff forms a matrix of services around us. That matrix which Jay showed before spreads across levels, individual, group, organization, state, at increasing distant levels.

For groups, you want three factors: communication, transport, workspace. Communication is how you knew to come here, transport’s how you got here, workspace is the building that you’re in. That’s more or less everything that you need in terms of physical assets for a civilized society. Six things to stop people dying, three things to help people form groups.

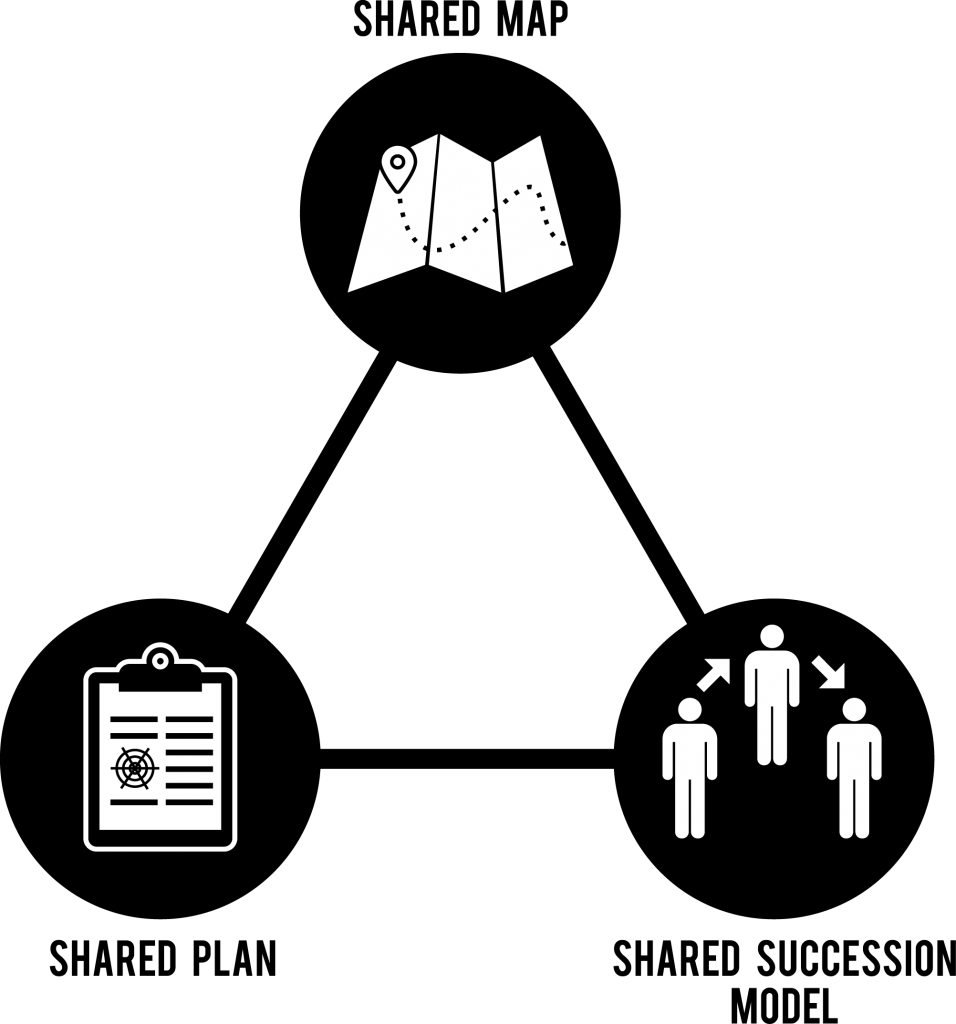

Organizations. Groups with special missions. An organization is a group that decides it’s going to do something. This is the architecture for that decision. You look at the map of reality that everybody agrees on, you make a plan relative to the map, and if the people that have structural power in that system begin to misbehave you get rid of them, and everybody agrees how to do that [inaudible].

From there you can move up to the state, again a complex structure. Effective organization, claimed territory, a list of citizens, international recognition, gets you a legal jurisdiction. And the legal jurisdiction is the equivalent of the succession model for the organization. It’s how you can make decisions.

Now, half of that stuff is not physical. The physical objects: too hot, too cold, hunger, thirst, illness, injury, communication, transport, workspace). The non-physical: resource control, shared map, plan, succession model, organization, territory, citizens, recognition, jurisdiction. All that stuff is just ghosts in the machine. You can build an arbitrarily complex and sophisticated set of ghosts in the machine, on almost no physical stuff. Athenian democracy ran in a really big square with people that shouted really loud. So we can have a complex, sophisticated society without having complicated stuff.

This is a map of how our society currently operates, using this scheme. It’s actually ten times more complicated than that, but it’s bad enough to get us started. Here’s your basic needs down one axis, here’s your tiers of political organization across the other.

But if you go back to the village level, suddenly the complexity drops enormously. Six basic needs, going out to the neighborhood or village level of organization, that’s a much more solvable problem. So even if you add communications, transport, and workspace, you only need to get nine things organized up to the village level in order to have a sustainable society that you can then build arbitrary levels of complexity on top of without increasing your physical consumption footprint. And that to me represents a manageable possibility. I can pretty much guarantee that if we put some real work into figuring out how to do the villages, we could plan, we could execute, we could succeed in producing villages that produce an essentially first-world standard of living on a fully sustainable basis.

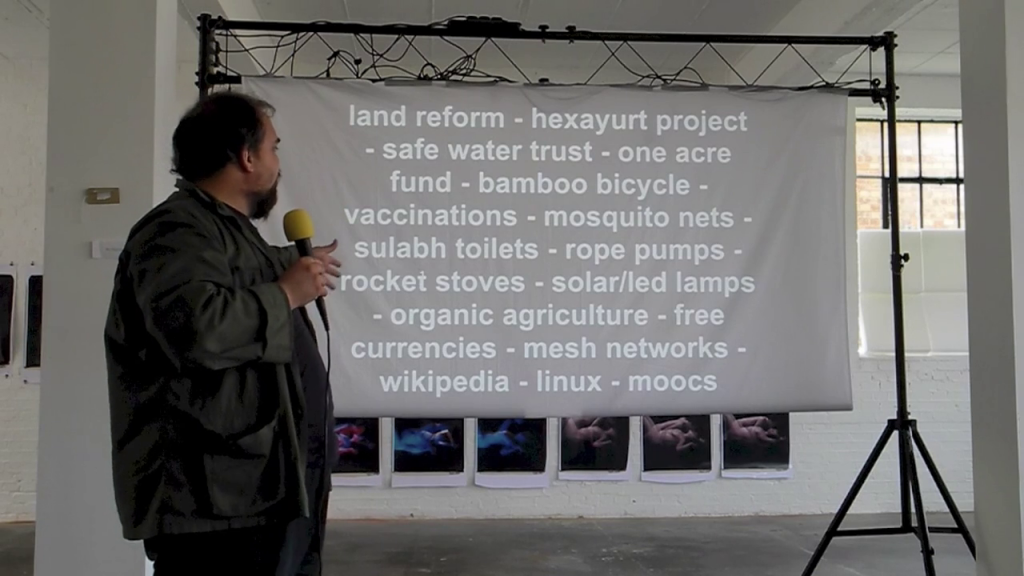

That is a list of technologies that I think are a third or a half of what you need to make the village work in almost any place in the world. It’s all there. It’s all little bits of plastic or cheap software or bits of metal. It’s things that could be manufactured to last forever. It’s a completely workable system.

I’m going to very quickly bang through a bonus round which was not scheduled, but it’s kind of timely. But I’ll take questions in two parts. When we get to questions, we’ll take some questions on the ongoing stuff of structural activism, but I want to talk very briefly about stacktivism and national security state. Basically, the thing that’s been taken off the political map and rendered invisible is the nuclear weapon. We stopped worrying about this stuff in 1990 when declared peace, and the reason that we can’t get any effective purchase against things like the NSA spying is because the nuclear weapon is not sitting under the NSA.

There’s the nuclear bureaucracy which is civilian nuclear power plants that make the plutonium, the enormous industrial base required to produce the submarines and the missiles and provide them plutonium, and then all of the additional infrastructure required to protect those assets from all threats foreign and domestic. The NSA and similar structures are basically just parts of the nuclear bureaucracy. It’s impossible to imagine putting so much pressure on the NSA that it goes away, or at least stops spying on us, in a way that doesn’t acknowledge it’s part of a much larger, much more integrated system.

That system now clearly includes Apple, Microsoft, and most of the big tech companies. They’re all part of this national security structure. The level of surveillance that we’re operating against is substantially higher than what was envisaged in 1984. In 1984, the viewscreen was not traveling in your pocket, and it wasn’t looked at by machines, it was still looked at by human beings. Because the hardware that we use and the software that we use are all interconnected into this huge system, the level of monitoring through the infrastructure which is owned by large companies, which are clients of the national security industry is absolutely enormous. So there’s a thread that goes from the cell phone in your pocket, through the operating system, then through the network, through the backbones, through the hardware manufacturers, all the way up to the nuclear weapons bureaucracies.

The last thing is you want to be extremely wary of cryptography because the traditional approach that security agencies have taken to cryptography is very simple. They allow your target to believe that their crypto is secure, and then they communicate on it as if it’s a secure channel and they read everything they say. That’s what the NSA’s dream world is, and there’s a long history of that state being produced by extremely subtle intelligence methods. So don’t trust civilian crypto. You might want to look at PGP 2.6.2, which is legendarily offensive to the state and therefore might have been secure at the time. Whether it still is is an open question.

We have to really think about operating system security in a completely new way. The path that we’re currently on is impossible to secure in the long run. We need to go back to looking at things like capability-based operating systems. And until we rebuild a secure communications infrastructure which is own and managed by the people we’re not going to be any further forward. Whitespace mesh network is worth looking at.

So that’s the end of what I have to say. The pitch that I want to make is it’s possible to manage the critical infrastructure build-out of free, safe, sane societies at the village level of complexity with existing technology and a bit of hard work. Everything past that is still speculative, but the stuff that we can do could potentially put half of the human race on a really solid footing without requiring them to come into the same rat trap that we’re in.

Thank you.