Thanks everyone for coming. Thanks to Waterstones for putting it on. Thanks so much to Gary and Kit for their patience, their hard work, their support. It’s been fantastic, and it’s been a kind of turbulent time and everything, but we got there in the end, which they did a fantastic job. And thanks to Chris for a wonderful cover. It looks absolutely brilliant. And thanks to Christiana and Caspian for an amazing amount of support and patience and just putting up with me for the past two years.

I was going to do just a reading from the book, and I thought because the images are so popular and people tend to like that, and for all the different readings and events we’re doing we’re just going to do different talks about images in relation to Imaginary Cities, this one I thought we would do a talk on London, because London’s been the city that’s really embraced the project, and the publisher’s based here, and everyone seems to really—it seems to have chimed with something in London

What I’d like to to look at is alternative versions of London, unbuilt buildings, different structures from fantastical literature (science fiction, that sort of thing), and just see how that reframes the city that we inhabit every day. How it makes us see it with perhaps new eyes.

This is from a comic. Brian Bolland did the artwork for it, and it shows the…well, as we all know, London was destroyed by Martian invaders. There’s a persistent thread through a lot of pulp novels and science fiction novels and comic books, of London being destroyed. It’s quite an interesting theme.

https://mobile.twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/529714308964683776

It actually goes around the world. This is from Pabel Utopia, which was a German science fiction magazine. One of the things I’ve been quite keen to show on the Twitter feed is we have a few of retrofuturism and this idea that the future sort of happened in the 1950s and we all have images of the Jetsons and this kind of American view of the future as this sleek, shiny, space age kind of thing, and one of the things I’ve been really conscious of doing on the Twitter feed is showing that quite a lot of different countries had the same approach. So you get Japanese variants of it, German variants of it. It’s the world over, really. Where there were comic books, there were people trying to imagine the future, and now those futures are kind of embalmed in the past, and how they sort of mark a time of possibilities that perhaps we have let slip away or were taken from us, really.

https://mobile.twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/615231361390149632

When I was a boy I used to read a lot of comic books, and what really interested me wasn’t the kind of tales of superheroes or alien planets or anything like that. It was this idea of taking identifiable spaces, cities that I recognized and had been in, and seeing how they could be transformed. One of the comics that I resonated most with growing up was Dan Dare, who was the pilot of the future from Eagle comic. The reason that he resonated was he took an identifiable London and put it through the prism of the optimism of that generation of the late 50s/60s, even just prior to the 1950s. The kind of futurism that you see in Dan Dare…

This tower I think was commissioned by Tony Benn when he was Minister of Technology. That really embodies that kind of futurism that really existed in London at the time, this idea that they were building a future that was going to be powered by technology and it was going to be for everyone, and this was reflected in the comics. So in a strange way, you have comics anticipating societal change, but you also have societal change being echoed back in comics. So kids were growing up in this stuff, and one of the things that has puzzled me is where has that kind of optimism gone?

https://mobile.twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/610438143909724160

This is an example of future London from Judge Dredd: the Megazine. It’s a form of London that has been absorbed. In Judge Dredd, London is known as Brit-Cit and it constitutes the entire south of England. But the thing that really struck me reading this as a boy was they retained—in a lot of futuristic comic books and science fiction novels, they have a tendency to just completely flatten what exists now and build from scratch so you get these crazy towers and space ports and all sorts of things. But the way cities work is that they’re almost always a collage, and there’s fragments of past eras and past architectural styles in with the futurist style, so you get this kind of collage of different eras. Lost eras, current eras, and Judge Dredd was really clever in that it wielded a real satirical swipe at Thatcherite Britain and Reaganite America. But it also recognized that the future already kind of exists. There are things now that will still be here. This building will be here in a hundred years’ time, two hundred years’ time, and it may be surrounded by the equivalent of whatever the Shard is in a hundred years’ time. But it’s that idea of the city is collage and previous eras surviving while others get submerged in them. Quite interested in Imaginary Cities of looking at why certain ones fall away and why certain ones are retained. What is it about them that makes us hang on to that particular era?

What I’d like to look at, aside from comic books and science fiction novels, you can always find these fantastical examples and talk about them all day. One of the things that really really interests me is architects who’ve built actual buildings, the architects who have designed the city that we’re in, almost every one of them has portfolios filled with unbuilt buildings and utopian plans and schemes. When we search through these arcades and we look at them, we’re really seeing forms of London that could’ve been and just never came to pass. So I’d like to just look at a few.

https://mobile.twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/474172273747034112

This one is Seddon & Lamb’s unbuilt Imperial Monumental Halls and Tower, from 1904. Westminster was beginning to become a bit cluttered. Too many statues, too many tombs, and they decided that it would be a really good idea to build this gigantic Gothic structure that was going to loom over Westminster. They were going to put all the excess tombs, shift Shakespeare, whoever; just put them in there and forget because they’d run out of room, essentially. I don’t know why it got cancelled, because it was pretty much a hare-brained scheme from the beginning, but I’m not sure how they manage to fit everyone in if there was no room a hundred years ago. I think they just got more discerning of who they put in there. The exact quote is that “it was a worthy center to the metropolis of the Empire, upon which the sun never sets.” But, of course, the sun always sets.

https://twitter.com/oniropolis/status/508213753054498816

This one is Charles Glover’s Central Airport from 1931. This was to be built on top of King’s Cross. It was going to be made out of reinforced concrete. It was going to have lifts that passengers could enter the buildings, go up the lift directly onto the radius, and there were eight runways that it could just take off from. They didn’t really factor in the fact that what happens if a plane overshoots the runway. It’d be absolutely horrendous, but it seemed like a good idea at the time. It actually got to prototype stage.

London’s #unbuilt Liverpool Street Heliport — as proposed by Kenneth Lindy & Winton Lewis, 1944. (From Barker & Hyde) pic.twitter.com/ipYvKbaq05

— Tim Dunn (@MrTimDunn) May 10, 2015

This was a genuine idea by a working architect. These ideas, one of the things I’m really keen to stress on the Twitter feed is the ideas that architects come up with are infinitely more insane than science fiction writers or fantasy writers. If you search through even the greatest architects—Frank Lloyd Wright, Walter Gropius—they all have these things hidden away, and I’m just absolutely fascinated by it because it’s visions of cities that might actually have somehow sneaked through. This conceivably could’ve happened it had just come in front of the right (or wrong) committee, and it would’ve got rubber stamped and we would’ve been living with it ever since.

That is Lindy and Lewis’ airport. That was going to go over Liverpool Street. It kind of makes the previous one look comparatively sane.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/509070214991208448

The third one was due to go over the Thames. You can see it there, it’s just like a table next to Westminster. people are going to go up the legs. There’s going to be lifts in the legs, and planes were just going to land there. It would’ve made a great photo opportunity for tourists, seeing the planes come in along the Thames, but obviously it would’ve been an absolute disaster.

There’s a lot of controversy at the moment about the Garden Bridge, and it’s basically an ongoing thing that’s happened in London over centuries. There’s been controversy every time a bridge—unless it’s completely mundane—there’s always controversy. Especially the Garden Bridge in particular. I don’t think the design’s spectacular or that controversial, but it’s the fact that it’s underwritten by public money and it’s going to be private space. Those are all arguments in themselves, but the controversy about building bridges, if they’re in any way imaginative, it’s just been incredibly controversial. So this one is Horace Jones’ alternative design for Tower Bridge, obviously. It can’t be lifted up to let ships under, thus defeating the purpose completely.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/474168840470134785

This is one of my favorite images of everything I’ve ever put online. It’s Holden’s version of Tower Bridge. This was designed in 1943. London had been absolutely pulverized by the Blitz. He decided, and he’s been criticized for it, a lot of people say at the time of the Blitz is it a good idea to design a pure glass Art Deco Tower Bridge? It’s not really ideal. It can be spotted from the sky in an instant. Really what he was doing, it’s quite an old idea as well, [was] having utopian aspirations in the middle of terrible, terrible circumstances. So during the first World War, Bruno Taut the German Expressionist architect, designed these glass palaces, and he intended to take over the Alps and instead of having the mountaintops he was going to create these glass palaces, and they were going to be an example of egalitarianism and a shining example that we’re all humans and there’s a sense of universal brotherhood and sisterhood. So in the depths of war you tend to get these utopian ideas coming through, which Holden embodies. I just think it’s really cool looking. It’s a great example and obviously there was no chance of it ever happening, sadly. But it may have been a kind of nice symmetry if it were built upstream from the existing Tower Bridge. There might’ve been a nice kind of balance between old and new.

The idea of the Garden Bridge is actually an old idea as well. This was the Crystal Span. Glass Age Development Committee in 1963 designed this. It was going to have shops, apartments, workshops and things, but it was going to have terraced gardens along the top. Again, it was a pretty utopian sort of ideal; it was going to an idea for everyone. And what we’ve seen in recent years is that a lot of visionary architecture in the past, the Bauhaus, the German Expressionists, Archigram, the Metabolists, they all had this idea of being extremely creative an imaginative to the point of appearing almost ludicrous, but they always had it wedded with an egalitarian sense of “This is for everyone. This is Utopia.” And what we’ve seen in the last twenty years has been a severing of that relationship. You tend to get the visionary architecture. There’s amazing architects: Gehry, Hadid, doing fantastic things. But they’re doing it for very few. They’re doing it for an elite, and the normal people of the city are basically being kept out, and that is something that needs to be addressed I think, as inhabitants of cities. This is a very old idea as well. The idea of having an inhabited bridge, even if it’s shops. You can see it in Venice. Various bridges in Venice have little shops and things. This was due to replace Vauxhall Bridge, so they were just going to get rid of that and replace it with this. It’s an interesting idea; it would’ve aged terribly. It’s really stylized to the time.

This is FAT’s Princess Diana-themed Millennium Bridge. Thankfully it wasn’t built. If you notice there, the lyrics of “Candle in the Wind” are carved along, and it would bring a tear to a glass eye. It’s just absolutely beautiful. When I first saw this I thought it was some kind of postmodern Jeff Koons-type satire, but it was an actual attempt.

These are the more ludicrous ones.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/518756521858334720

This was a tower that was due to be built on top of Selfridges in 1918. Just taking an existing building and putting a massive Venetian-Greco-Roman monstrocity… It’s postmodernism before there was even Modernism. It didn’t know it was postmodernism, but it was. I think that got surprisingly far before someone put it out of its misery.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/508546928863608833

This one was Joseph Paxton’s Great Victorian Way, which was 1854. This was a fascinating project. Again, it got pretty close to actually becoming reality. It was designed to loop ten miles around central London. It was going to be a massive glass arcade filled with… The age of great arcades as what Walter Benjamin wrote about. But this was going to be so big that you could take horses and cart through it. It was going to have all the shops. To me this is the kind of futurism of the time, because this was absolutely at the cutting edge of not only constructing buildings (because glass had just recently become possible to manufacture in this scale quite cheaply) but in terms of the shops it was going to have. It was going to have the latest of everything. So this is not just the equivalent of and impressive shopping mall. This would’ve been Dubai or Singapore-level. It got stopped I think at the last minute, which is rather a shame. It would’ve been interesting to see how London would’ve dealt with being essentially besieged by a giant ten-mile glass structure, and how we would’ve driven buses through it, but I’m sure they would’ve worked it out.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/517708892785373185

This is a really fascinating one. It always reminds me of Giger. It’s like something from Alien. This was designed to be on the South Bank, for the Universal International Exhibition, 1951. Incredibly far ahead of its time. Actually, I don’t know if it’s actually incredibly far ahead of its time or incredibly in the past. There’s something like a made Byzantine futurism to it. Misha Black and Hilton Wright designed this one, and it was pretty much going to consume most of South Bank. It was going to have a giant spiral ramp which forms a framework on which buildings rise in terraces to a sky platform 1,500 feet above London. They knew that people were going to be skeptical, so they said, “If it doesn’t work on the South Bank we’re willing to move it to Hyde Park or Regent’s Park. We could just plunk it in the middle somewhere.” It’s fine, no one’ll mind.

But it’s a fascinating exercise. I’m very glad in a way it it didn’t get built, but it’s really interesting how people envisaged space. The idea of having terraces rising up to a sky platform, and even the language “sky platform” is stuff that we hear all the time now when we hear about smart cities and these kind of megacities, we hear there’s a sky platform or a sky lobby and you can go there and have nice drinks and get charged an extortionate amount of money. They were thinking this in the 1950s. So they were possibly so far behind that they were way way ahead.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/533678776761475073

This one’s really interesting because this is where we’re currently sitting. This is Piccadilly in the year 2500, according to Greys Cigarettes. You used to get these little cigarette cards and they would put interesting things on them, and Greys decided that they would commission people to come up with visions of future London. I don’t know if you can see but there’s a massive glass dome, several glass domes, and it’s got monorails. I think this was made in 1935. So again this was pretty far ahead of its time. Those sort of images became cliché in the mid-1950s. There’s a lot inaccuracies. It’s not very clear from the resolution of this one, but one of the little bus/train/moped things has got Greys Cigarettes on the side, so they envisaged that Greys would still be a household name. They didn’t foresee lung cancer. What they did foresee, and this is in their words, was “moving pathways, rubber roadways, motors driven by atomic energy,” so all of these vehicles have some kind of atomic generator inside them, which would be worrying when they break down. “Phonetic spelling,” which I think is the best thing that they envisaged of the future. All these amazing constructs, but also we’ll spell phonetically; that’s the important thing. “Wireless television,” it’s lit by captured solar rays, and there are excursions to Mars. So this would’ve been in Piccadilly; this would’ve been here. And it isn’t, which is a shame.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/537959378033582081

This is Richard Rogers, again highly-respected architectural practice. He came up with this design called “London As It Could Be” in 1986, taking a lot of influence from Japanese Metabolists and also Space Age Googie architecture and the futurism of the 1950s. This was actually quite accurate and it obviously looks very little like what has become of London. But there’s a lot of predictions that he made in this project, like the pedestrianization of a lot of city spaces that did actually come true that Richard Rogers was actually involved in as well.

In the midst of coming up with schemes that are very easy to laugh at, they do exert pressure and they do exert a certain influence that can sort of reverberate and reappear in unexpected places. Also, as happened with Archigram, who did a lot of their work in London, you can look at these ideas of walking cities and flying cities and it’s very easy to just point and laugh at them, but really they’re clearing a lot of theoretical space and asking a lot of questions of what architecture actually is. And these can have unseen reverberations many many years later. I think that the mainstream architecture that we see today with Hadid and Gehry and people like that is only really accepted as mainstream because of people like Archigram really putting their necks on the line in the 60s and getting laughed at. They cleared the space for what we now just completely accept. They took the flak, essentially, and in my view organizations like theirs were really almost heroic in the sense of pushing things forward.

https://mobile.twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/556104473542942720

Not all ideas are good ideas. This is Charles Bressey’s improvements to London, 1937. You can probably tell where that is. Not the idea place to put a multi-story car park. It would make sense to park cars there, but it’s an absolutely catastrophically bad use of space.

The next one is his as well. This was a genuine thing that was put to the government at the time, was pondered over. There is a certain kind of diabolical beauty to it. It’s a horrible desecration of London, obviously, but there’s also a lot of predictions. There’s a certain sort of prediction of Brutalism there, for 1937. There’s a lot of linear cities putting motorways over the tops of buildings that was very popular at the time, like Corbusier was going to redesign Algiers, turning it into a motorway with houses underneath, and it was stopped, thankfully. But what interests me about visions like this.

This is another one of Bressey’s. It’s the idea that things can be impressive, intriguing, and horrendous all at the same time, that we have a tendency to think that just because something is horrible we just casually dismiss it. But just because something’s horrible doesn’t mean it isn’t interesting. It doesn’t mean it won’t have certain reverberations. So I think that by dismissing things that we disagree with (for example the Shard), if we disagree with what the Shard represents or its use of public space or how it appears in the skyline and its effects on the dynamics of London, that doesn’t mean it isn’t an interesting building and that we don’t critically examine it and properly interrogate it.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/578106751335067648

This was going to be for Trafalgar Square, 1815. Colonel Trench decided that it would be an ideal place to put a pyramid. Just the way you have outsider art, this is outsider architecture. It’s a ludicrous idea, of course, but it’s an interesting one and it’s quite interesting to see where it’s come from in terms of Western society’s outlook towards the Orient at the time and Arabia. This actually says a lot about our view at the time of the rest of the world, on the Orientalism there. You can see it in lots of major cities. You can see it with Cleopatra’s Needle, how colonialization was just taking bits and pieces for themselves, and then trying to do pastiches of it. So you find pyramids and strange structures appearing all through major cities; Brussels, Paris, London. And some of them still remain, so it’s not quite as half-witted as it seems.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/508342177316216832

Another pyramid. This is Thomas Willson’s Metropolitan Sepulchre. This was intended for five million corpses, so it was going to be a gigantic tomb. There was obviously of where are we going to put all the dead people. Let’s house them all in a giant pyramid. There must have presumably been staircases. This was designed by the Pyramid General Cemetery Company (fantastic name) and it actually got as far as Parliament before it was shot down. So it was seriously considered. It would’ve been this gigantic memento mori constantly reminding everyone in London that they were going to die. Five million corpses staring at them as they made their way to work. It was actually going to take over where Primrose Hill is. Primrose Hill was going to go and this was going to be in its place. And it got as far as Parliament.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/578506284204466176

There is actually a purpose to looking at these aside from just laughing at things. It’s the idea that the city could’ve been vastly different, and came very very close to being different. This is Joseph Gandy’s Western Gateway for London, 1826. It was going to be a giant archway. I don’t think he envisaged that London would expand so much it would be impossible to have one entrance, but this is the entrance that he envisaged, so he’s seeing people coming through this. Again it says a lot about London’s role in society at the time. It was the great city of the time. It was pretty much the Roman Empire, and this is a great example of how London saw itself. It was the new Rome, and they tried to signify this by doing pastiches of Greco-Roman architecture to say all roads lead to London, essentially.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/596706815716544512

This was Kohn Pedersen Fox’s proposal for Canary Wharf. This was in 1990. Canary Wharf being one of those places that has been imagined pretty much from what it was, even within living memory, but this is one of the alternatives that it could’ve been, and again came surprisingly close to being. There’s certain interesting aspects to it. In one sense, it embodies the futurism of the time, what they were going with the Lloyd’s building; things like that. It also looks like a kind of chemical factory that Batman would chase the Joker into and he’d fall into a vat.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/456408245586759680

The visions are still continuing, so you get all sorts of architectural studios and designers that are constantly coming up with new visions of where London’s going to go. The vast majority of them won’t actually come to pass, but that’s not to say that they should be excluded, because they do have echoes and they do have unlikely influences. And often the stuff that’s very easily dismissed, it’s just a question of time. So you have the example of the French visionary architects around the time of the French Revolution. They were just treated as eccentric for at least a couple of centuries, LeDoux and Boullée. They had these kind of weird globes and cenotaphs to Newton, and they were just treated as kind of follies until modernism realized looking back in retrospect these people were actually prophets. So for two hundred years they were laughed at, until society caught up with them, and then their time came to pass. They ended up informing Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus. So just because something looks crazy now doesn’t mean in a hundred years’ time it won’t actually profoundly influence the way a city is.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/526824315107700736

This is Laurie Chetwood’s Inhabited London Bridge.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/579284142040477696

This one is really interesting; it’s 1967. Desmond Plummer and the GLC’s abandoned plan (sadly; it got pretty far) for a monorail on Regent Street. We walked around Regent Street today; it was going to be a monorail, like something out of the Simpsons. It was just going to go overhead. Again, it looks kind of very stylized to that era, but it says a lot that space was prime real estate. They wanted to hang on to as much pavement space as possible. They didn’t want to extend the roads. They wanted to build there, so they thought let’s just cram in as much as we can. Let’s have a monorail, let’s take things above.

Showing these images, there’s a sense that the city could’ve been different, and it came very close in some instances to being different. What I’d like to look at with these next images is the fact that it was different. That London was a different place, and a lot of the assumptions that we have are very recent ones.

Many of you will know this one. This is the Crystal Palace, and it was built for the Great Exhibition of 1861. It was known as the Great Shalimar. It was a massive engineering feat of its day. It was the biggest construct in glass of the time. It was one of the man-made wonders of the world from an engineering point of view. It was one of the most visited structures; six million people visited that exhibition. Most of them went through the Crystal Palace, and it was visited by Dickens, Charlotte Brontë, Lewis Carroll. It was a massive engineering feat. It designed to show the British Empire as the foremost superpower of the time, and it did it very well. And it could well still exist. Unfortunately it was moved from its original site to a less-distinguished site and it burned down in a fire. It was relatively neglected for a long time. It was one of the most popular buildings in the world. We should technically still have it. It was a freak fire, and because it was lined with wood it just went up in flames.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/508662075431084033

Less well-known is Skylon, which some people within living memory will still remember. This was built in the South Bank for the Festival of Britain. As unusual as it looks, it was a really beloved structure. It was seen as embodying the dynamism and the futurism of the time. This was an age of optimism. We were going to conquer space, we were going to solve poverty, we were going to do all these amazing things, and we were all going to do it collectively. It was built to show off British prowess in terms of engineering. From far away you couldn’t see how it was held up, so it was seen as a kind modern and vaguely miraculous. It was scrapped by Churchill and the Tories because it was deemed too Socialist, and they thought that it was as symbol of a future Socialist, Constructivist Britain that they didn’t want. And it’s kind of reminiscent of Russian Constructivist structures, so they weren’t actually far wrong there. But it did embody the optimism of Britain at the time. Churchill had it scrapped.

There was a lot of controversy about what actually happened to it, because it just vanished. For a long time, there was an urban myth that it was just dumped in the Thames. It’s the sort of thing you might notice just floating down the Thames, this kind of massive Martian structure. But it was melted down for scrap and some of it was turned into little souvenirs, so people got keepsakes of it and they’re hidden away in places. But yeah, that was the future that was unfortunately cancelled. Not for the first time.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/530664031800279040

This was the attempt known as Watkin’s Tower. It was an attempt to build a London Eiffel Tower. They went to Gustave Eiffel, who built the Eiffel Tower, and tried to get him to come to London. The Eiffel Tower was so successful, despite an incredible amount of opposition to it at the time. It was built for one of the Expositions. It was put up; there was a massive amount of controversy that it was (aside from Montmarte) despoiling Paris’ beautiful flat landscape. There was this massive, extremely radical Modernist structure that went up, and the writers and even the architects at the time mostly hated it. There were petitions against it. Maupassant hated the Eiffel Tower so much that he didn’t want to see it, so he used to go and have lunch in the Eiffel Tower, because it was the only place he was guaranteed he wouldn’t see it.

So it was absolutely hated, but quickly Parisians fell in love with it, because it became symbolic of their city as a whole. It came very close to being knocked down, which people don’t generally realize. They were going to get rid of it after the exposition was over, and the only reason it stayed, supposedly, is because they ran a lot of telecommunications through it, and it was a great place to send out signals. So it stayed. So there is a parallel universe where the Eiffel Tower was completely scrapped.

This was going to be London’s version, so they tried to get Gustave Eiffel to come over, but he was too nationalistic and—I love the French, but typical Frenchman he said it’s an insult to even ask a Frenchman to replicate the Eiffel tower for London. So they decided to go ahead anyway and just steal his idea, build and almost identical replica of it. They were going to put it in Wembley Park. They opened the competition up and these are some of the submissions. It just went out to the public, so you get all sorts of architectural practices sending designs. You actually just get people in their drawing rooms coming up with these insane structures, most of them based around the Eiffel Tower, the middle one [#6 here?] based on the Tower of Babel. It hasn’t been popular for a while. Various pyramid structures. These are fascinating; there’s 68 of them, that were collected in a book at the time. I think they should’ve built them all, just around London. There should’ve been 68 mutated versions of the Eiffel Tower. Just an entire city of them.

They began building the previous one, the one in Wembley Park, and they got up to the first level. So if you’ve been to the Eiffel Tower, the level that you can go up on. They had the legs built and the first shelf, and it started to subside. They realized it’s not a good idea to continue but what can we do? We’ll try and get ways around it, and they eventually ran out of money trying to work out how to fix it. So they just blew it up with dynamite, and it became known as Watkin’s Folly.

Somewhat diminished by having it in a field to begin with. The beautiful thing about the Eiffel Tower is you can stand in that promenade and look down at it. Just having it in the middle of a field would kind of ruin the attraction. Where Watkin’s Folly was originally located is actually Wembley Stadium now. So again, that may have been different; it came exceptionally close to being different.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/522078256733122560

This actually existed. It was known as Wyld’s Great Globe. It existed from 1851 to 1862, in Leicester Square. This was a real structure in a massive globe that you could go in. You can see the people for scale. You’d go inside and you went through a sort of Orientalist, kind of Arabian tunnel and you emerged in this massive almost like a cavern inside. What it had on the walls was a giant replication of the world, only inside out. You went up the stairs and you could see the world all around you. So it was a sort of globe, but from the wrong way round. It existed for over a decade in Leicester Square, until it was blown up. They had a fondness for blowing things up at the time.

It was kind of seen as a Ponzi scheme. The Wyld who ran it was a notorious fraudster. He was a member of Parliament; the two are not unrelated. He bought lots of votes and became a member of Parliament. He made some of his money creating guides to London, and he would invent destinations that didn’t exist. He’d just invent train stations that didn’t exist. It was seen as a massive folly, but it was incredibly popular and it was visited by hundreds of thousands of people, if not millions.

Previous to that, Leicester Square had been a wilderness and was a really run-down, Dickensian area that was avoided by people. The kind place that stabbings happened; an incredibly deprived area. And that could conceivably still be there in Leicester Square.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/531018026544816128

This is a painting of Old London Bridge. Going back to the Crystal Span bridge earlier, the idea of the inhabited bridge became very popular in Modernist times, from the 30s to the 50s. There was always this idea in American architecture about building luxury apartments in bridges, and you see a lot of designs around the Hugh Ferriss time that space was so restricted in Manhattan and places, that they were going to just stick loads of buildings on the tops of bridges. It’s a very old idea, and it actually existed in London. Old London Bridge used to have those buildings on it. People’s houses, businesses, if you strolled through there were markets, and again part of the idea of Imaginary Cities is looking at what we think we know and see and that it’s actually much more unusual when you look into the history. London is a fascinating place. It used to have frost fairs in the Thames, where the Thames froze over and they would have fairs in the middle of the Thames and ice skating, and they used to have businesses right in the middle of the Thames.

So alternative Londons not have existed in people’s imaginations, they’ve existed physically as well.

London’s been destroyed previously. During Roman times it was burned to the ground, and the Great Rebellion, the Iceni rebellion, they burned London to the ground. There’s still a layer of soil in certain parts of London that’s sort of carbonized, and you can find it. Beneath all the strata, you go down and there’s a burnt level of soil from when London was completely burnt to the ground and was rebuilt. It’s been rebuilt many times, after the Great Fire, after the Blitz. So the idea of London as this inevitable, natural, God-given thing that’s just always existed… It’s a completely ever-changing, amorphous, plural thing. All cities are really like that. All cities are multiplicities, essentially.

Perception is kind of the key to recognizing that multiplicity, so even in a very simple sense, we all share the city physically. We all live in London, or we all travel around London, but we all view it in infinitely different ways, and we have our own routines and our own places that have special significance to us, and symbols and resonances that are particular to us. So while there’s one London City, there’s actually a million Londons.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/569093137945247744

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/561900576083283969

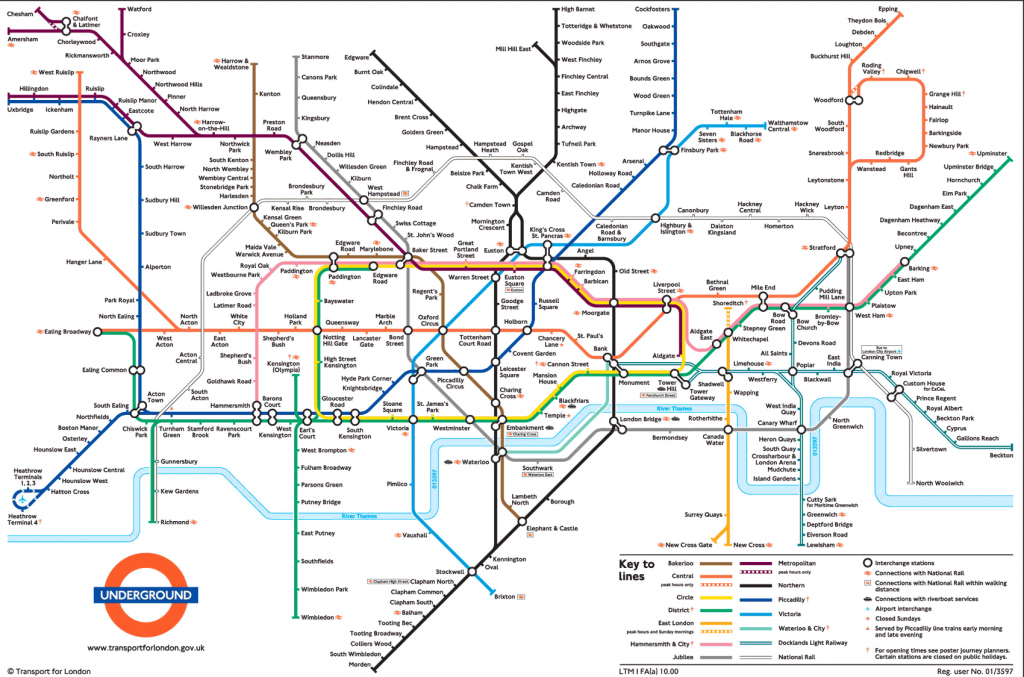

This is Cyril Power’s version of the London Underground. It’s a kind of strange, Expressionist vision. We’re in the Underground every day. We see it certain ways, but everyone really sees it differently, and when we look at a poster like this we’re reminded that it is actually quite a strange thing, having a massive network of tunnels that we just seem to go underneath—T.S. Elliot said there’s something magical involved in going underneath and reappearing as if by magic somewhere completely different.

This is a map of the Tube, the kind of Lovecraftian horror it, when you look at it. It’s just this many-tentacled beast. But we all have these personal mythologies and resonances, and they enable us to see how strange the city actually is. It’s very easy to forget. It’s like what Blake said, you can see Heaven or Hell in a grain of sand. It comes down to context and relativity and your own perception of things.

https://twitter.com/Oniropolis/status/562924951628689410

A prime example of it is John Martin, the painter. This is his version of Pandemonium from Milton’s Paradise Lost. It’s a city in Hell that Satan inhabits, and it’s obviously based on Westminster. Make of that whatever you will, but it’s a great critique. He happened to sneak it in and I think Milton would’ve—I don’t know if he would’ve approved or not, but it’s got that certain iconoclastic attitude.

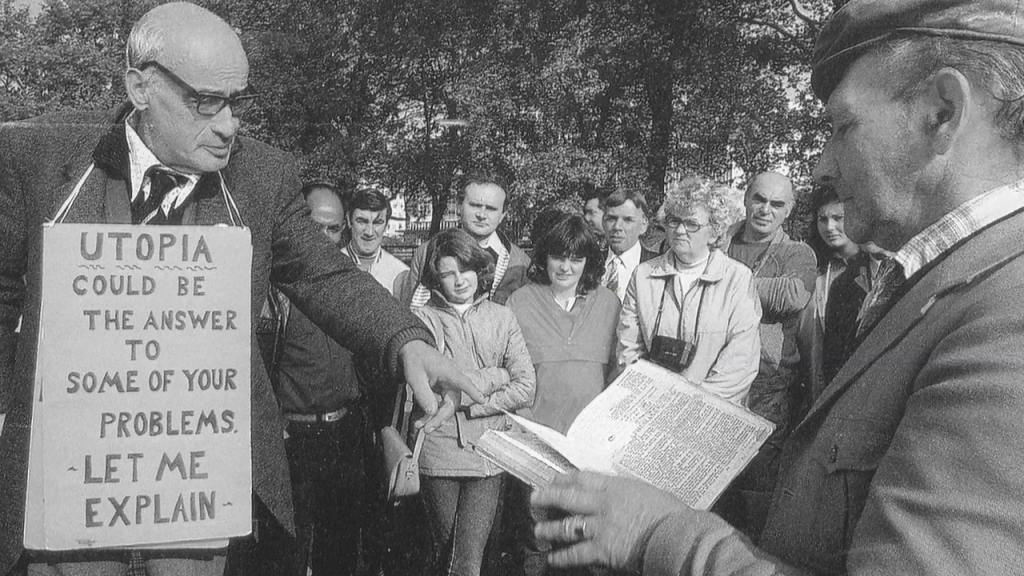

My friend pointed out earlier, it could be the answer to some of your problems, not all of them. But this is Hyde Park. This was taken in the 60s or 70s, going by the dress sense.

What I was going to say is, alternative London’s are all very well. We can look at them and see how amusing they are, or interesting they are, or just ludicrous. But it kind of reminds us that the city has been imagined into being and there could’ve been different ways, it was different ways. It’s been imagined, and if a city has been imagined into being, it can be reimagined as well. When we look out at the skyline of London, you look at any of these streets, we’re not looking at something that’s just fallen from Heaven or it’s just come packaged that way. It’s not natural or inevitable.

Every one of these buildings, the entire skyline you see is the result of decisions by people in the past. It’s the dreams of architects and city planners. Every single thing you see, someone has decided to have it that way. And if that’s happened, we tend to think that nothing can change, we’re locked into these structures, we can’t do anything about it. But beginning to realize how the city evolves, we can actually have an input into it, and we can suggest alternatives and push for alternatives. At the minute, I think a lot of decisions are being taken out of our hands. There’s a real democratic deficit in terms of who says what’s built in the city, in terms of the way the city looks, and it’s something that really needs addressing because it’s a city that we’ve helped imagine into being, and it’s a city that we can reimagine into being again.

Every tower doesn’t have to be luxury apartments for oligarchs. Every tower doesn’t have to be for finance. There’s a million designs that show towers to culture, to science, to music, to philosophy. There’s no reason whatsoever that these things are impossible. There’s a million blueprints and countless architects that’ve designed them. We’ve just lost the sense of imagination and daring, but also the egalitarianism. Why are we being excluded from these places? This is our city as much as anyone’s, and it’s important to begin to realize that London is that multiplicity and that it can be changed, and it will be changed. And if it’s not changed by us, it’ll be changed to our detriment, and we may well be excluded. You’ve seen it every day in the news every time another tower goes up, we’re lucky if they let us in. We have to pay, there’s all sorts of zones of exclusion now that are coming in. It’s really something that we can fight, and it involves going back and looking at the likes of Archigram and the early Bauhaus and the Expressionists and the Constructivists, and reimagining what we can actually do and having it for everyone. So a city that can be imagined, as London has, can be reimagined. Thanks.

Audience 1: I want to ask one question first, that being do you think London is one of the most imagined cities in the world? Are there others that you can draw on that you think are of equal reimagining? And is it the amount of flux that London’s gone through in ancient times?

Darran I think it ties in with colonialism a lot. So you see London is definitely one of the most imagined, and I think that’s because for a long time, the size of it—it was one of the great metropolises. So any city of that size will have massive amounts of buildings and massive amounts of architects and movements and various things happening within it. Every city, though, has unbuilt designs, absolutely every one. I’m from Derry; it’s a small town in Ireland. I went down and found these insane designs that were going to take over all the riverfront. Floating buildings in the 1960s and stuff. So you can find them absolutely everywhere, but the main cities are the great metropolises, because that was where the money is, it’s where talent tended to go to find work.

You find it in Tokyo. Tokyo has been imagined so many times by the Metabolists, among others. You find it in Berlin. New York, obviously. Those intrigue me a lot because it’s good to see competing, and how they clash a lot of the times, how the various movements bounce off one another. But they’re everywhere. The idea for the book came when I was living in Phnom Penh. Phnom Penh’s been actually reimagined in the 1960s. It started off as a Khmai capital that’d had been moved. They had Angkor Wat as this massive jungle capital and there’s some debate about why it went wrong, but the capital shifted to Phnom Penh. So it was native Khmais. The French went in, they built French plantation architecture you still see remnants of around. Then it got independence and it became… There was a Prince Sihanouk, he had this strange 1950s and 60s sort of psychedelic rock bands groups and girl groups. It was an amazing, happening place. It was known as the Pearl of Asia. It was a fantastic place.

The Vietnam war came along. It completely destabilized the country, and the Khmer Rouge took over. The Khmer Rouge with malicious utopianism emptied the city of three million people. That city became a ghost town for three or four years, and since then it’s been taken over. It’s got a virtual dictator now who’s suddenly bringing in a lot of Chinese money and Russian money and Western money, and they’re starting to build skyscrapers and stuff.

So there’s one name for Phnom Penh, but there’s so many incarnations of it, and that’s pretty much every city. That’s an extravagant example, and a pretty tragic example, but every major city, possibly every town, has variations of this. So you can go everywhere. They also all have the same problems as well, gentrification, the theft of public space into private hands, the spread of [?]. It’s all there, the same questions. But it’s happening primarily in London. London’s a focus point, just the way New York is or Tokyo is or Berlin. They become focal points for something that’s pretty much a human drama that’s unfolding in every city. But London has countless examples.

Audience 2: Do you [inaudible] parallel universe?

Darran Yeah.

Audience 2: What is there in London now that somebody is laughing at from a parallel universe? I imagine there’s one with a runway at Westminster.

Darran Yeah, they’re laughing at us. If you’ve ever been to Stansted, that is infinitely worse than any airport on stilts. To be honest, there’s countless examples. But then it comes down to aesthetics. I could give a list of buildings I hate in London. I could give a list of buildings I love. It’s not really the issue. I think almost the buildings I hate are the ones that interest me the most. So I look at the Shard and I think there’s something about it I really can’t stand, what it represents and how much of an imposition it is. But it’s actually a very very unusual building. There is a lineage that not many people talk about that comes from German Expressionist Utopian architecture. Amazing designs from the 1920s, and those go right through to the Shard. So the Shard is a pretty weird building. It’s an interesting building. It might be a horrendous building, but that would just be a kind of aesthetic judgement, or an ethical judgement. I think what’s important to me is that it’s an interesting one.

I’m very interested in context in terms of cities, so I’m very interested what would happen if you lifted the Shard, or a better example, if you took the hotel in Pyongyang that looks like Skeletor’s base or something. It looks like horrendously dystopian oppressive architecture. It’s this massive pyramid, all black glass, and it’s really totalitarian-looking. I’m really interested if you lifted that and you just put it down in Dubai or put it in Singapore or put it in London, how certain people’s opinions would change. We like to think that we have these pure opinions about things, but it’s completely contextual. You can take something that’s massively oppressive, put it in the right context… If the Shard was in a Walter Gropius notebook—he didn’t draw actually, so it’s a bad example. But Frank Lloyd Wright was going to design a mile-high tower and we look at these designs, or Tatlin’s Tower in Russia, we look at them and we think, “Wow, fantastic, this mind-blowing tower.” If the Shard was in his notebook as well, we’d probably think the same. We’d probably think, wow that’s amazing.

And it works the opposite way. If Tatlin’s Tower had been built, we’d probably hate it. It was a tower that was going to have rotating cylinders that you’d be inside, and one would rotate once a year and the other one would rotate once a day.

Audience 3: Do you think that’s more of an immediate reaction to something as it’s being built. People hate the Shard now; it might be something that people embrace in five years’ time or—

Darran I think that’s precisely the case. It’s totally right to hate the Shard for what it stands for if you want to. That’s fine. I do resent that the great ambitious towers are going up to finance and commerce. It’s a massive waste of imagination. But you’re right. It’s when it appears in the skyline and it’s blocking things out that it really gets to people. Paris is a pretty extreme example because London has always had these structures. It’s got hills, it’s got things that are always in the way. Paris is almost completely flat, so that was a real, real act of heroic vandalism, if you like. It was just putting it there, and like it or lump it it’s going to be there. So people have this resistance initially, but opinions change. A lot of the stuff that we hate, we end up loving. Within recent memory, the Millennium Dome—I’m not saying it’s a good structure, by any means, but that was absolutely reviled at the time. It was seen as a massive waste of money. I’m not sure it still isn’t reviled, but people see it as a functioning—

[Audience; inaudible]

Darran I’ve seen Nine Inch Nails there, it was fantastic. Because the context of it has changed and there’s been a bit of time, I don’t know if people have warmed to it, but they’re warming.

Audience 4: Do you think there is a difference in the way different cultures imagine the future of their cities. You mentioned that London’s been destroyed several times and that idea of getting rebuilt within the city’s DNA, as opposed to somewhere like New York which has had pretty iconic structures and has never had that kind of complete [inaudible] like Berlin or Tokyo [] Do you think there’s a significant difference between the way that different cultures imagine their futures?

Darran Most definitely. A lot of it comes down to compulsion, really. A lot of the ciites that’ve changed dramatically like Berlin were simply blown to pieces during the wars, so they had to be reconstructed. And they were reconstructed in various ways. There’s an incredible amount of impressive buildings around Berlin. There’s also interesting totalitarian aspects. One of the reasons Friedrichstrasse, Camargue[?] strasse, or Rosa Luxembourg Strasse, wherever it is, they’re built so that Soviet tanks can fit down them if Berliners decided to get uppity and tried to do another Prague Spring.

So that has a massive effect, but different cultures definitely have different attitudes. There’s a Japanese idea, I can’t remember the term, but it’s a semi-religious idea that everything’s transitory. So there’s these temples in Japan that get burned down every thirty years and rebuilt. And they sometimes get rebuilt exactly the same way, but it’s all about reminding ourselves that life is a cycle and it’s transitory.

So from culture to culture there are differences. I think what happened with New York is that they just got the formula perfect early on and it stayed that way. But it’s changed a lot, too. You think of Penn Station, this monumental, amazing structure desecrated because of progress. And there’s been expressways built, not through Manhattan, but through parts of New York. A lot of people like Jan Jacobs railed against this tendency in the 1960s and 70s to knock down a lot of neighborhoods and build expressways through them. Also, New York was once New Amsterdam, and before that it was Manhatta. The Native American’s had it. It and Paris are the closest places we have to places that were never bombed and have stayed relatively consistent.

But even they’ve changed, and attitudes have changed. How we envisage the future I think often comes down to fashion, and I think certain things take hold, but any culture who doesn’t recognize that cities are going to be collages is going to run into problems very quickly because every attempt to build… You see semi-successful versions of it like Brasília and places that have built from scratch, one overarching person should not be dictating what a city is, because that’s not really a city anymore. I don’t know what that is, but it’s something else. A city is inherently a collage.

Further Reference

Companion site to the book.

A short video with excerpts of the launch event at Waterstones London.