Ben Hammersley: So as you just heard, my name’s Ben Hammersley, I once invented the word podcast—I’m sorry, I apologize.

So I work as a futurist. And a futurist’s job is to live a few years in the future and then come back and tell you all about it. And so that’s what I was going to do today, but then I thought well actually, no. I was here yesterday. And I was talking to lots of people, and I was going to some of the talks, and I was hanging out outside and playing the pinball machine next to the coffee thing, which is very good if you wanna play with that.

And I was thinking I actually this audience is slightly different. You are slightly different to the usual audiences that I have. You’re taller, for one thing. More than half of you are women. Which is awesome. And you’re also quite sophisticated. And so I thought well actually, what is it these people want? What is— Like, if I was a product designer and I was designing my talk, what would I want? What does the user want? What do you want, right.

And I already had a talk written. And…I deleted it. Which was probably a bad idea twenty-four hours before giving it. So, instead I thought well what do these people want? And actually they want to learn about the future.

Okay. So usually, if you’re a futurist, one of the ways—what a lot of people in my profession do is they’ll stand on stage like this and they’ll show about 150 slides of very cool technology. Usually very shapely technology. Sometimes there’ll be some skyscrapers with trees growing out of the top. There’ll be a lots of sort of biomimetic stuff from Brazil and things like that. And there’ll be about 150 slides as I said and they’ll just sit there and they’ll go through it and it’ll be very—it’ll be almost pornographic.

And you won’t learn anything but at the end of it you’ll be quite excited for Christmas. And I call that the Victoria’s Secret Offering. And I’m not going to give you that today. Sorry. There’s some cool stuff outside, alright. When you get coffee, go and have a look outside.

But instead, what I want to do is I want give you the tools to do my job. This is obviously killing my entire career in Scandinavia, but nevertheless. Let’s do this. Okay. So are you ready to become a futurist? Fuck yeah. Okay!

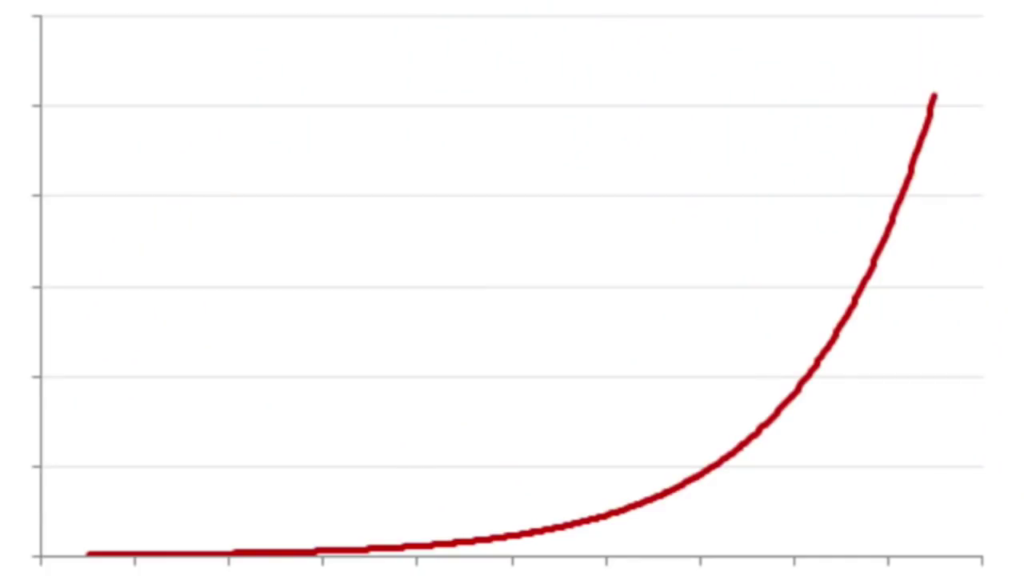

Right. This is the most important graph that you’ll ever need to use as a futurist. Every single futurist has one of these as the first slide in their deck. It doesn’t really matter what this is. An exponential curve, up and to the right. This represents all of technology. The past thirty years of technological evolution is described in this. This could be anything. This is processor power. This is memory per dollar. This is Internet penetration. This is the number of people playing Angry Birds. This is the number of iPhones. Whatever it is, up and to the right, an exponential curve. It is insanely important to understand this. Because no one. does.

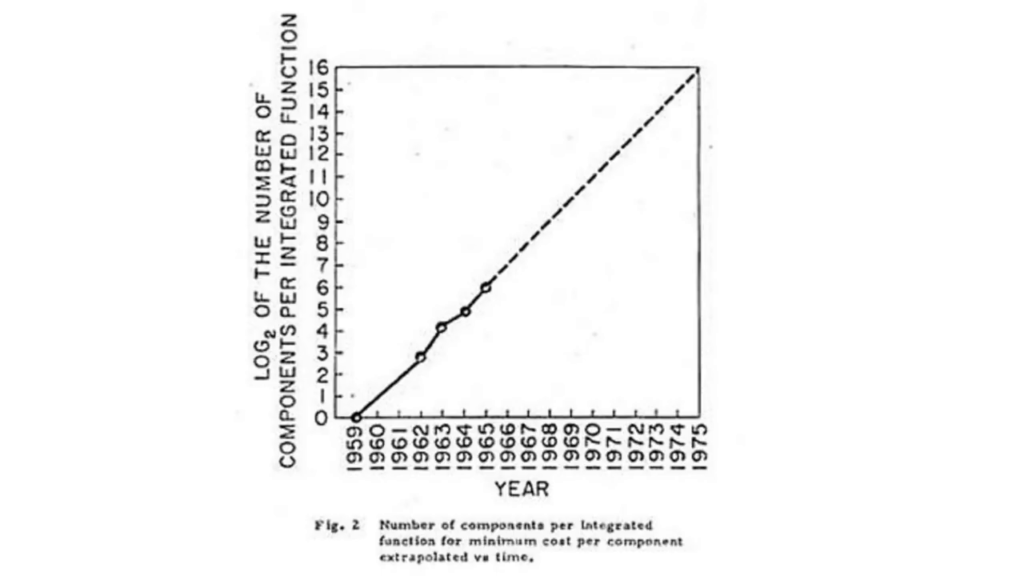

Let me show you where this came from. The most impressive exponential curve—up and to the right—was invented by this man. He’s called Gordon Moore, who is the cofounder of Intel. And in 1964, he looked at the sales brochures that Intel were publishing of the chips that they were making, and he realized there’s was an interesting pattern. Every year, for the same amount of money, Intel could fit twice as many components on to one of their microchips.

And he wrote an article about this in a magazine. And because he was an engineer he didn’t use an exponential graph, he used a logarithmic graph, which makes a nice straight line. This is very annoying when you show this on a slide. Because not only do people not understand exponential graphs, they certainly don’t understand logarithmic graphs. But nevertheless, this shows a doubling of the number of components that can fit onto an integrated circuit every year.

This is called Moore’s Law. And it’s perhaps the most important thing that you can understand to understand all of the modern world. Because what Moore’s Law says is that every year for the same amount of money, computing power doubles. Now, everybody in this room…even the old people at the back, everybody in this room has lived the majority of their lives if not all of your lives in a world where Moore’s Law has been the most important thing, right. You understand this fundamentally. It is part of your being. You know that every September, Tim Cook from Apple will stand on stage like this and instantly make the phone in your pocket shit. Right. This is an iPhone 10, and up until September I thought this was the best phone ever made. I now realize it’s terrible and I need to buy a new one. This happens every year because of Moore’s Law, the doubling of capability for the same amount of money.

Now why is this important? Well it’s important because human society does not understand a doubling of capability. Because for thousands of years before, our technologies did not get twice as good every year. In the old Viking days, swords did not get twice as stabby every year. Horses did not get twice as fast every year.

Now why is this? Well it’s because we use digital technologies to make the next generation of digital technologies, right. You don’t use a sword to make another sword.

You use a horse to make another horse. That’s true. That’s true. But. But, they didn’t…they stopped getting faster. The upgrades…they’re terrible.

So this is a real problem, because as a futurist, you get paid more for having a further away forecast horizon. The forecast horizon is how far out into the future you can talk sensibly. Now when my industry was invented in the 60s by the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica in California, about a mile—literally a mile up the road from where I live… When they invented it, their forecast horizon was about twenty years. And actually if you read the reports that they wrote in the early 60s, they were pretty good. Pretty bang on. They were pretty clever.

Today though, our forecast horizon is roughly…three years. Anybody who is making technological predictions for more than five years away is entirely bullshitting. To use a technical phrase.

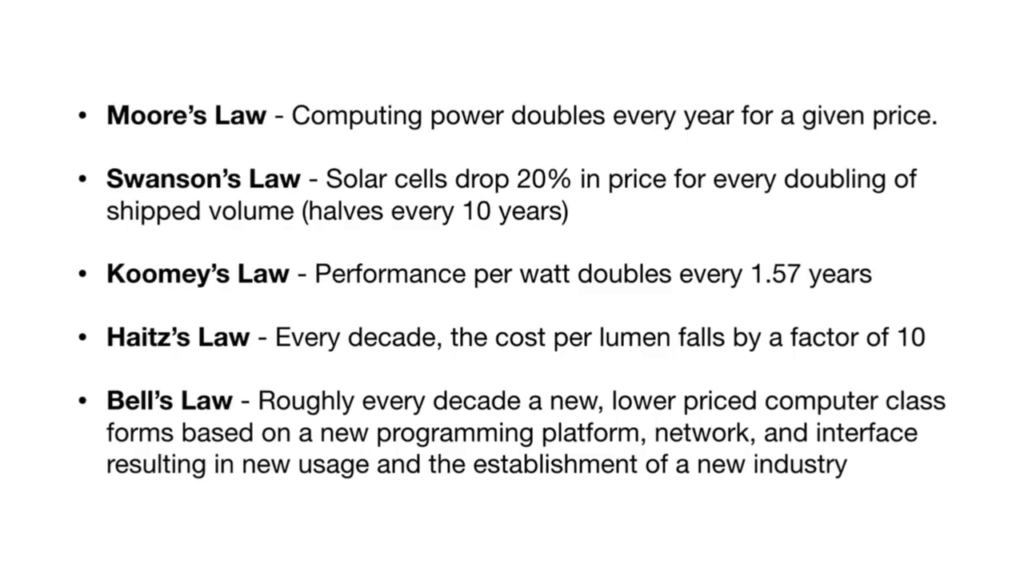

So this is a real problem for us if we want to be futurists. So how do we do this? Well what do we do? Well, we have to use what we call rule-based scenarios. This gives a little bit of rigor, a little bit of scientific fact for you to base all of your imagination on. There are many rules that you can use. The first one is Moore’s Law, the one we said. This is a very complex slide, please do not read it. But there are many other rules that we can use. But roughly they all say the same thing: that for any technology that you can think of, it kind of gets twice as good roughly every year. From processor power, to batteries, to bandwidth, to screen resolution, to screen size, to solar panels, to all of those things.

So you take these general rules of thumb and then you apply them to real-world observations. You spent a lot of time out in the real world, looking at the way that people do stuff. Not necessarily looking at technology, but looking at the way people act in the world. The way that people’s day-to-day lives are changing from week to week, from month to month, and from year to year.

Now why do we do this? Well because as futurists, we have to recognize that along with technology we have enormous amounts of simultaneous change, because with technology you have society and culture all changing at the same time. Twenty years ago, roughly, when this conference was first started, it was an incredibly technical conference. You had to have a beard for you to be allowed in the room. But now it’s both technical but there’s also a huge amount of society and culture as well. Because all of these things are equally as important, and feed off each other. If it was just techies in the room, they’d be utterly irrelevant. If it was just social scientists in the room, they’d be utterly relevant. If it was just people making culture in the room, also irrelevant. You add them all together, you get the real thing.

And so as futurists we have to pay attention to all of these things, and at the same time we have to be looking to see what the people are doing in the streets. Let me give you an example of this in action. So about two years ago I did a project in Los Angeles where we were looking for new technologies and trying to extrapolate them out to wider implications. And we noticed as we walked around the streets of LA, just before—actually…this time of year, just before Christmas, there were lots of people riding about on those little hoverboards. Do you remember those? The little skateboard—like, horizontal skateboard‑y things that kept exploding, right.

Now these were really interesting for a couple of reasons—well for many reasons. From a technological point of view they’re incredibly interesting because their batteries were strong enough to hold enough charge to carry a heavy dude like me up and down the beach. That was new. They also had electric motors which were powerful enough to carry a heavy dude like me up and down the beach, powered by one of those batteries. That was new. And at the same time, with other research we were seeing computer vision and AI happening.

We also saw in many cities around the world this new urbanization, that young people were moving back into the downtown areas. Especially in Los Angeles. Downtown LA twenty years ago, it was utterly abandoned. It was basically a slum. It was pretty rough. Gangland. Now it’s insanely fashionable. Hipster. Gentrification. The whole thing. And so there’s this return to downtowns. And at the same time we found that there was a generational rejection, specifically in North America, of car ownership.

So we took all of these different things—the technological, the cultural, the social, we added them all together. And we wrote a report, and the report said sometime very soon, all these things are going to come together, and they won’t be explody hoverboards from dodgy Chinese factories. Instead they’ll be some form of interesting urban platform, interesting urban product.

About a year ago these started to appear on the streets of Los Angeles and also other major cities around North America and now the world. You don’t have these in Stockholm yet I don’t think. You do. Well there you go. Brilliant.

You know what these are, right? Now, here of course, the next six months, probably not that cool. But in the summer these are awesome. They radically change the way a city thinks, actually. They radically change the way a city operates. And if you have thousands of these, which we do in Los Angeles right now, the local councils have to start thinking about the way the roads work, because they have to put in more bike lanes because more and more people are using these. Now this is really cool, because this leads us on to the next stage of the technological revolution.

Here is a picture of my daughter (she’s the one at the top) walking to school being followed by her robot. The robot is a Loomo. It’s a prototype robot from Segway. Now, you may recognize this if you have a Segway. You may have seen some some of the Segways that’re about about this high and you can stand on them and you can ride them around. Well Segway who make those also have a robotics arm and they make a robot that uses the same self-balancing technology.

Now why is this interesting? Well, this contains all of those technologies that were in the hoverboards and all the technologies that’re in the mopeds…and the Lime and Bird and all those scooters. Adds in artificial intelligence, which has doubled and doubled in power every year. Adds in computer vision. And so we can stand on this and we can ride it around, and then when I step off it I can turn round and I can talk to it. And I can say, “Loomo,” that’s it’s name, “Hey Loomo, follow me.” And it goes beep beep, “I will follow you now.” And then when I walk down the street it follows behind me. Or it follows behind Ripley my daughter.

Now this is pretty useful, because it means I can take her to school every morning on one of these robots. But it’s also incredibly useful because when I go shopping I can ride the robot to the shops and then on the way home I can buy a coffee, put all the shopping on the side of the robot, and walk home and the robot will follow me.

Now why am I telling you this, other than to tell you that I’ve got a robot and you don’t, ha ha ha. Why am I telling you this? Well, this is because as futurists, you have to think about these implications of these technologies for the next…you know, two, five, twenty-five years. What are the implications?

Well, the first implication is this stuff already exists. Which means that if today you look at that and you go oh that’s a bit rubbish, next year it’ll be twice as good or half the price. The year after that, twice as good or half the price. Year after that, twice as good and half the price. Again and again and again. Which means in three or four or five years’ time, those things will be incredibly cheap and pretty good.

And then you start thinking well what are the use cases? Well sure, crazy hipster dudes that live on the beach with tattoos and a 4 year-old, pretty useful. My grandmother who really likes to go to the market to buy her food, but can’t carry the bags anymore? Super useful. When I go on holiday and I’m going through the airport and my luggage just follows behind me… Because it recognizes my…ass I guess, and follows me, right. Also very useful.

And if that’s the case and that’s the case, well if I was an architect and I’m designing an airport or a supermarket, or if I’m a town planner designing pavements in the shopping districts of cities, then I need to pay attention to this stuff. Because when I build a large building it’s going to have a twenty-five year lifespan. Which means that today, now you know about these robots. If tomorrow you were employed to design or help design an airport, you have to make sure there are no steps anywhere. Not necessarily because tomorrow people are gonna have these things. But because in five years’ time people are gonna have these things and if you’re the one who has an airport with steps in it, everybody’s going to hate you.

So as a futurist, your clients are gonna be looking to you for things that are gonna happen in five years’ time, and you can see what those are from the small clues we have today about this rolling forward of technology, that it doubles in power and doubles in capability every year. And we can see this sort of evolution.

Now. “This is all very well, Ben. I feel energized. I’m ready to change my career. Let’s do this, all of us together. Fifteen hundred of us—let’s do this. Let us start our own futurist town. We should become a cult.”

But no. Because there is a problem with this. In California in Silicon Valley, there is this general feeling that technology is destiny, right. That if you can invent something then it has to become true. One of the underlying psychologies that’s sort of behind Zeynep’s talk just now, that comes from Facebook, is if Facebook invented it then therefore it’s possible therefore Facebook have to use that technology, right. They have this feeling that if it exists, they have to use it. And holding back on something that they could do for the sake of people feeling a bit freaked out by it, it’s not cool, as far as Silicon Valley is concerned. And so sometimes we sort of fall for that hype, right. We fall for this idea that if a technology exists, it’s going to happen.

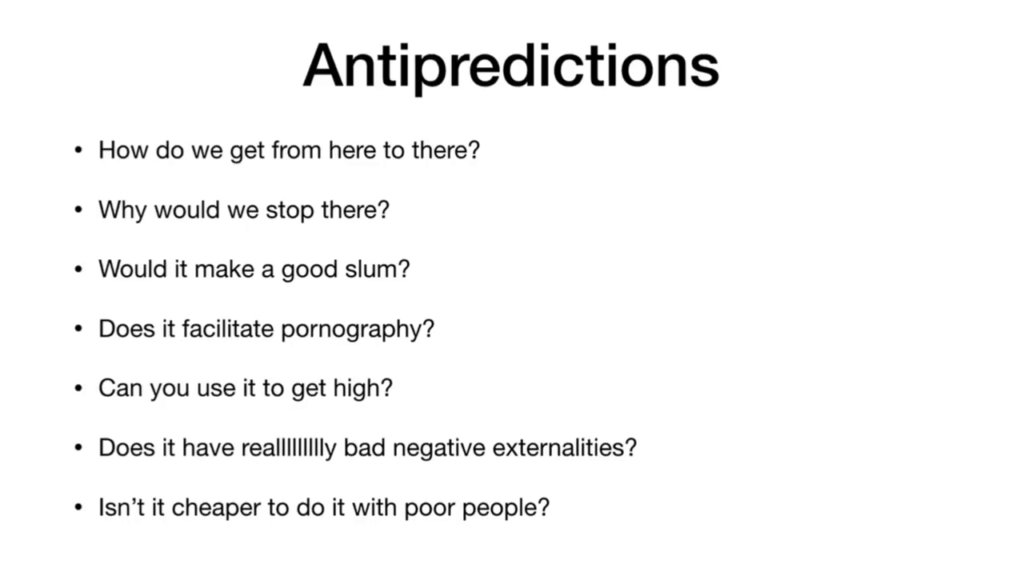

And this isn’t necessarily the case. There are actually some questions that you have to start asking about your predictions, just to check them. To make sure that they’re sensible. So here are some of these questions. These are very good questions if anybody ever makes a sort of prediction about something in front of you. You can run through these questions in your head and you can probably, or almost certainly, find a problem. And that problem will either end the argument right there or start a new conversation which will invent something better.

So for example: How do we get from here to there? Now this is a particularly good question if we’re talking about utopian visions. Science fiction films of the past twenty years have had enormous amounts of utopian visions of cities. You might be able to bring some to mind of a city for example that’s under a dome, and everybody’s dressed like they’ve just come from the Gap. And everything is incredibly clean, and beautiful. And there’s usually some rebels, right. And those beautiful dome cities where everything’s clean and beautiful? Total nonsense. Because there’s no way for us to get from here to there.

At the same time, though, there are also lots of other films which are incredibly dystopian, where everything has gone to hell and it’s all crazy and like cyberpunky and a bit Blade Runner, all that sort of stuff. And again, those are wrong, too. Because we have the second question: Why would we stop there? If we got to a shitty place why wouldn’t we keep on going and try and get out the other side? Again, questions that we have to ask.

If we’re talking about about buildings in a specifically new housing and urban developments, one good futurist question to ask is would it make a good slum? The best parts of the best cities of the world have gone through multiple cycles of being incredibly rich, and then incredibly poor, them incredibly rich, and then incredibly poor. In the same areas. And many new housing developments, many new expensive housing developments around the world, would make terrible slums. Which means they’re doomed.

There are many more of these. The most famous, and the most you know, entertaining one of course is, does it facilitate pornography? If you see a new technology and you can’t work out how to make porn with it, it probably won’t work. Very important.

These are all questions we have to ask. We have to be critical, we have to be thoughtful, we have to be mindful about technologies. Not just get excited that a thing exists, but start to ask really important and difficult questions about them. And about their lifespan.

As I say here, thinking about technology means thinking about culture, which means thinking about politics, which means thinking about technology, which means thinking about culture, which means thinking ab— And around and around and around we go.

And if you are in any way, in any part of your job, responsible for thinking about any of these things, you have to think about all of them. This is really the lesson of the past decade. If you’re thinking about any of these things you have to be thinking about all of them all at the same time.

Let me give you an example of this: disruptive technologies. We hear the word “disruptive” all the time and it’s considered to be an incredibly brave thing. But the question you have to ask yourself, is something really, truly disruptive? The Google self-driving car, for example. Positive evidence that Google can make software but cannot design a car for shit.

Self-driving truck. Is it disruptive? No. It’s not disruptive in any way because it doesn’t change anything thing about the industry. All it does is replace a human with a robot, but it doesn’t change anything. Genuine disruption in the transport mechanism would be a self-driving bus. Or lots of buses. Or a change in planning facilities which means you have higher density housing that’s closer to work so you can walk to work. Or trains that work. Or something like that. Genuine disruption would be bicycles. Not cars. Self-driving cars are not a disruptive technology. They are in fact the last stage of a failing technology. We have to think about technologies in the way that they relate to all other things.

What you think is normal, as I say, isn’t new, at all. And if it’s new it won’t be normal. Now it’s not a bad thing that we don’t get this. Malcolm Gladwell in his last-but-one book posited this theory that said that for you to become a master at something you had to do it—you had to do deliberate practice, thoughtful deliberate practice in something for 10,000 hours. For us to be any good at digital technologies, any good at understanding the Internet, this would mean that everybody would’ve had to have spent an hour and a half a day every day for the past twenty years.

Now…Twitter doesn’t count, right? So, nobody’s done that, yet. We haven’t had enough practice. And so there are some things that we need to think about before we can move on and think sensibly about technology. We have to think about changing morals. Here’s a thing you can do if you want to be a really good futurist. It’s called The Grandparent Game. Everybody here has grandparents or great-grandparents who have social beliefs which you find incredibly offensive. Probably they’re mad racist. You don’t have to answer but it’s true, right?

Next time you have a big family dinner… If we were in America it would be Thanksgiving on Thursday, but Christmas or whatever, right. This is a good thing to do after the second bottle of wine. Ask everybody what beliefs you hold that your grandchildren will find incredibly offensive. What things do you think which you hold to be absolutely true, will your grandchildren or your great-grandchildren think you’re an absolute asshole for thinking?

And if you can start to think in that way, you’ll start to be able to think about the way that technology is evolving and the way it’s changing politics and so on. We call this the Overton Window. The sphere of political debate that is possible within society. And the Overton Window shifts all of the time. And being able to predict the way that the Overton Window is shifting, by thinking through those sorts of questions, is another way to think about the effect of technology on the world.

Now I have precisely a minute left so I’m going to go super quick. Hold on.

The problem that we have about technology today is that the overall overarching culture of innovation is the idea that innovation is brought to you by a single person: the messiah. The young man in the hoodie who comes out of the desert with a tablet with the magical code on it. And every organization and specifically every government has had this idea in their head for twenty years. That somebody will come along with a new app which will save them.

This is not the case. In fact, the real case for genuine innovation is that everybody, the whole community has to do it all at the same time. But most organizations cannot do this. Because most organizations do not live in the present. When it’s 2018 in this building, in the city hall next door it’s 2006. So we have to get ourselves right up to the present day before we can move forward.

So for my last thirty seconds I’m going to show you how to do that. This is a technique…that I want you to take home with you…and use…mindfully and powerfully because it’s incredibly powerful. Are you ready to learn this technique?

Am I allowed an extra minute on my clock? Awesome. It’s just coffee after me, so you’re fine. Okay.

We call this technique “constant legacy-free reinvention.” Here’s how you do it. The next opportunity you have, and let’s say tomorrow, from the moment you wake up to the moment you go to bed… And this will slow you down tomorrow, okay. You’re not gonna get as much done tomorrow but this is really worth it. From the moment you wake up to the moment you go to bed, I want you to think about every single action that you take, every single physical action you take, and ask yourself two questions about every single physical action.

The first question is, what problem am I solving by doing this action? I am drinking from this glass of water because I am thirsty. I am brushing my teeth because something died in my mouth overnight. Whatever it is, right. I am sending this email to move this project forward, right. Whatever physical action you’re taking ask yourself that question. What problem am I solving by doing this thing?

The second question is, if I had to solve that problem today for the first time and I had to use modern tools, how would I do it?

Now this is going to slow you down, as I said. Because at every point you’re gonna have to get your phone out, you’re gonna Google stuff, right. But when you do that, what you’ll find is that for many of the things that you do, the sheer act of asking the question “what problem am I solving by doing this?” you’ll find that a good percentage of the things you do, you have no real reason to do them. So you can stop. Now that’s a good innovation. Just don’t do it anymore. For the remaining stuff, quite a lot of that stuff you will find a new and better way of doing it simply because you never bothered looking before.

Now when you do that, and if you do this on a regular basis both individually and inside your family and inside your organization, inside your neighborhood, when you do this, very rapidly over the next few weeks and months you will find that you’ll bring yourself right up to the present day. And you’ll bring your organization, your family—whatever it is—right up to the present day.

And when you’ve done that, when you bring yourself right up to 2018, 2019, whatever it is, then you’ll find that your view of the future and your ability to make strong and smart and insightful strategic decisions will be much much improved. Your life will be better. You’ll think clearer. Your skin will clear up. You’ll grow two inches taller. And everybody will love you. But more importantly, you will be able to think clearly about the effects of society on technology and technology on society.

We face enormous amounts of problems brought about by the lack of contemporariness of thinking. We have entrusted in many cases our future to people who are confused by the present. So for those of you in this room today, your mission is not to sit back and wait for things to happen. Your mission is to bring yourself right up to the cutting edge and stay there, and lead everybody else into the future. And if you start off today, leading into the future is really easy. You just do it one day at a time.

If you can do that, when we meet again next year this room is gonna be super awesome. Thank you very much.

Moderator: Thank you Ben Hammersley. My idea for the Overton Window, and I think I can already picture my grandkids asking me, “You used to eat cows and pigs?” Like meat, right. Are you… I mean, there’s all these things that we take for granted today that we grew up with that are going to be totally so old-fashioned and weird. I think that’s a good way of thinking of it.

But, so in Sweden we have an ongoing discussion about old people mainly who do not want to use the Internet. They don’t want to be part of modern society. They don’t want innovation. They wanna use forms and call people and do things the old way, dammit. And you whippersnappers with your Internet and your blippity bloppity, you shouldn’t come here and change things. How do we deal with like, this natural stretch in society where you have a huge part of the society that moves on and moves into the future, even if as you say slightly a bit slower than maybe this room? How do we deal with having that mass of people and not leaving half the population behind? Because like, you had scooters for instance. Electric scooters. They flood the cities, and then the city goes, “No. We’re gonna ban the electric scooter because they’re taking up too much space.” And so how do we marry these two worlds together? If you could just answer that in fifteen, twenty seconds?

Ben Hammersley: Sure. So, I think you’re falling into the Californian trap, right. In that in some cases… Not all of the ca—definitely not all of the cases. But in some cases, those old people who want to do everything on paper, they might be right. Making something digital does not equal making it good, right. Doing it on an iPhone doesn’t make it—making it “futur‑y” doesn’t make awesome. Doing it in a VR headset basically makes it suck, right?

Moderator: It might be cool but not great.

Hammersley: Right.

Moderator: Yeah.

Hammersley: And so these newly-qualified futurists here, they understand. Because they were listening, right. They understand that for everything like that, you have to ask yourself, if I was doing this for the first time and I had to do it with all of the tools available, or with choosing all of the tools available, how would I do it? And that implicitly means choosing the correct tool for the job. Absolutely, there are many things where doing it on your phone, or doing it online or whatever, is by far the best way of doing it. But there are other things which are much better done on paper, or in another way. And there’s considerable research coming out now for example in the education field, where we’re realizing that writing stuff down by hand, even temporarily, even if you just write it down and then throw it away, right. Writing stuff down, you learn it better, for example.

Moderator: More than typing, you mean. Or more than—

Hammersley: Something like 20% better than typing, yeah. The measurableness is very marked, right. And so…now it’s not surprising, as I was trying to say, it’s not surprising that we don’t fully understand that. Because we haven’t been doing the digital stuff long enough to go, “Well actually, we’re kind of experts in this now. We know it sucks in this particular area.”

But as more and more research is done, and as all of these beautifully-qualified people are now able to think about these things in a bit more critical way, they’ll be able to say, “Hang on a second. When I go and see a lecture and I type my notes I don’t remember any of it. [crosstalk] But when I go see a lecture and I write stuff on paper…

Moderator: Well shit, what am I doing with this thing. [sound of tablet being dropped on table]

Hammersley: Prec— See, welcome my friend.

Moderator: Well, it might not be a futuristic robots to take your child to school, but it’s at least a plastic R2-D2.

Hammersley: I saw Zeynep get this and I was like they’d better give me one.

Moderator: Thank you so much for an inspiring talk.

Further Reference

Internetdagarnda 2018 archive