Alright. Well, I’m here to start off the morning by talking about money and happiness, and what science can tell us about how we might use the former to get the latter. In particular, I want to suggest that money can both aid and impede the pursuit of happiness.

Now, I first became interested in this issue a few years back when I myself suddenly came into a lot of money. When I say that I came into a lot of money what I mean is that I went from being a graduate student to being a faculty member. So, I realize that most junior faculty aren’t considered wealthy. But we academics have one great advantage, which is that we make so little money as graduate students that suddenly having an actual salary feels like being instantly wealthy.

So this brings us to our first lesson about money and happiness. We human beings are sensitive to change. So we like it when money falls from the sky, when we suddenly experience an increase in income. But like Dan Ariely’s frog, we adapt with remarkable speed to our newfound wealth. In fact, once people are making about seventy-five thousand dollars a year, additional income ceases to have any real impact on people’s day-to-day happiness.

Now, this is a puzzle. After all, much of economics and public policy rests on the assumption that increasing the wealth of individuals and nations provides a route to increasing their wellbeing. So why does money fail us?

Well, we stumbled across a novel answer to this question quite by accident. In looking at a data set that my student had collected for completely different reasons, we happened to notice that the more money people had the less they reported savoring the little pleasures of daily life. So following up on this bit of serendipity, we conducted a larger study and exactly the same thing popped out.

So for example we asked people to imagine coming across a beautiful waterfall while on a hike. The more money people had, the less likely they were to say they would jump in and hoot with joy, or even to stand back and pause to really appreciate the beauty of this moment. Now, this is important because the ability to really savor life’s pleasures is important for happiness. So this helps to explain why it is that the relationship between money and happiness is relatively weak. At the same time that money does all kinds of great things for us, it also seems to get in the way of our happiness by impeding our ability to savor. So the idea here is that if you have a lot of money or even just kind of think about money, you feel like you can get whatever you want. So you don’t really need to savor every little morsel of pleasure that comes your way.

So can we really blame money? Is this money’s fault? Does wealth actually cause us to savor less? Well, to find out we would love to make the people instantly wealthy, maybe here in the audience today, see what happens. Unfortunately we can’t do that. But, psychologists have developed ways to make people temporarily feel and behave as though they themselves are wealthy. In fact, all it takes is showing people a photograph of a big stack of money.

Now, the reason why this works is that we all have powerful networks of mental associations with the concepts of money and wealth. So it’s pretty easy for us psychologists to tap into these networks, switch them on, and see what happens. So we wondered then whether just showing people a photograph of a big stack of money might actually make them savor less.

So to find out, we conducted an experiment very much like one that many of you have already participated in this morning. On your way into the theater, many of you were probably offered a little piece of chocolate from my lab. Some of you may have noticed that for whatever reason there was a photograph of a big stack of money on your chocolate. For others the same photograph was blurred beyond recognition.

Now, I want to suggest to you that those of you who saw the photograph of the big stack of money on your chocolate may have enjoyed your chocolate less. I realize this sounds a little improbable, but that’s exactly what we found in a recent study.

So we went up to people on our campus at the University of British Columbia and we just asked them to eat a little piece of chocolate. Right before they ate the chocolate, we showed them a photograph of a big stack of our colorful Canadian money, or a neutral photo. Meanwhile, we had stationed observers nearby who could surreptitiously watch our participants eat their chocolates. What we found was that people who have been exposed to the photograph of the money spent less time eating their chocolate and exhibited significantly less enjoyment of it, as rated by our observers.

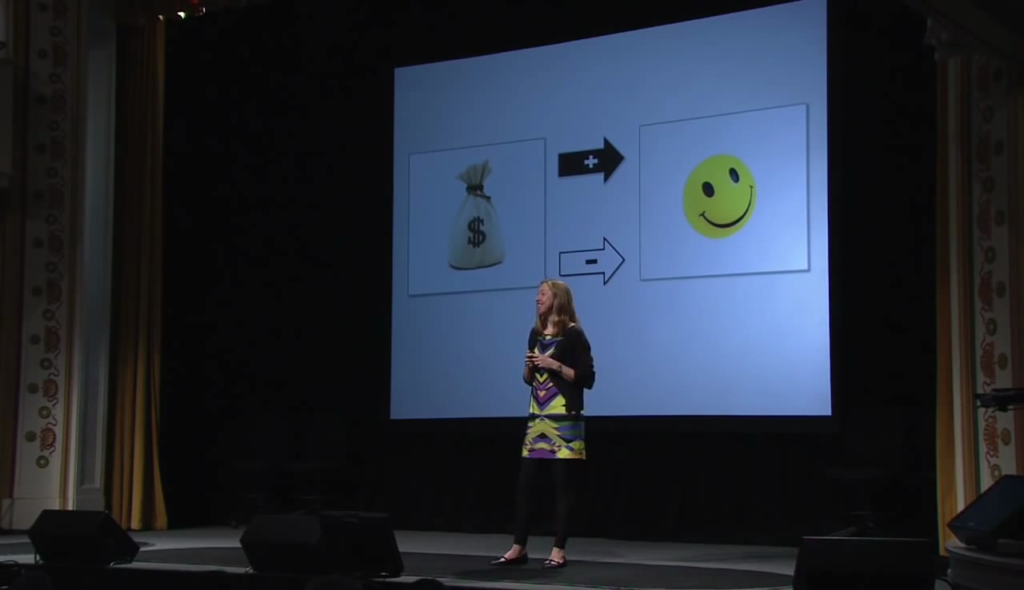

So this suggests, then, that money can actually get in the way of happiness by undermining our capacity to savor. But if you go back to work on Monday and your boss is really happy that you went to PopTech, and wants to offer you a big raise, I don’t want to suggest that you should turn it down. So, the relationship between money and happiness is positive. It’s just that this relationship is a lot weaker than most people assume. And our research helps to illuminate why by speaking to this white arrow.

So, in the second half of today’s talk I want to turn to the black arrow and think about how we can squeeze the most happiness from our money. Now, this turns out to be a challenge. As Robert Frank put it in an article entitled “How Not to Buy Happiness,” “People do not spend their extra money in ways that yield significant and lasting increases in measured satisfaction.” In other words, people don’t spend their money right.

So, armed with my newfound wealth and a team of graduate students, I wanted to figure out how people could use their money better. In particular, I wondered whether people might actually get more happiness from spending their money on others rather than on themselves.

Now, to test this I had to make a little money fall from the sky. So we went out on campus and just handed people either a five a twenty-dollar bill randomly in the morning. And we asked them to spend this money by 5:00 PM that day. We told some people, “Hey, we want you to spend this money on yourself.” We told others, “We want you to spend this money on someone else.”

So what did people do when they found themselves with this bit of extra cash? Well, when we told people to spend the money on themselves, they did things like buying hearings, eye shadow, and food or drink for themselves. By contrast, when we told them to spend money on someone else, they did things like buying toys for younger siblings, making donations to charity, as well as buying food or drink for friends.

So the question is which type of spending will leave people happier at the end of the day? Well, when we called people back that night, participants who had been told to spend the money on somebody else were significantly happier than those who’d spent the money on themselves. Of course we conducted this experiment in Vancouver. We conducted our other initial research in the United States. So we wondered whether we might really be looking at North American phenomenon. Many people have portrayed North America as a kind of culture of excess, so maybe our finding is really limited to this rather weird cultural context.

We thought, however, that maybe we were looking at a broader human phenomenon, in which case we should be able to detect the same kind of effect elsewhere in the world, even in much poorer countries. Now, at the time it just so happened that my fiancé, who is an environmental engineer, was conducting some volunteer work in the East African nation of Uganda. So I asked him whether between finding safe, clean sources of fresh water for the people of Uganda, whether he could also maybe find me some collaborators in that country. He succeeded, and with the amazing help of these local collaborators we were able to conduct simultaneous research in Canada and Uganda.

This time rather than making money fall from the sky, we wanted to see how people spent their own money in their day-to-day lives and look at the emotional consequences of that real-world spending. So we asked people to look back and really vividly reflect on a time when they’d spent money on others or on themselves. So we asked people to think about a time they had spent either twenty Canadian dollars or its equivalent ten thousand Ugandan shillings. We’re giving people in the two countries the same instructions. Half the people are told, “Hey, tell us about a time you spent this money on yourself.” Half are told to tell us about a time they spent the money on somebody else.

Now, even though we gave people exactly the same instructions, the kinds of spending experiences that people described in these two countries were very different. For example, in Canada one person wrote when asked to talk about a time when they’d spent money on someone else, they wrote, “I spent $20 for 2 dozen red roses from Costco for my mother’s birthday.” Very nice. Very different from what we see in Uganda, where for example one person wrote, “I gave money to a friend of approximately 12,000 Ush to buy medication for his aching ulcers.”

Now, I have to be honest with you. When I was reading through these questionnaires, I thought to myself, “Okay, we are heading for a necessary failure. We are not going to replicate the same effect that we’ve seem in Canada in Uganda,” because the spending experiences people were describing just seemed so different. And yet, to my surprise we found exactly the same effect in both countries, whereby people felt significantly happier when they looked back and reflected on a time when they’d spent money on others rather than on themselves.

So having seen these robust effects around the world, we wondered whether the benefits of financial generosity might extend beyond the individual to teams and organization. So to look at this idea, we teamed up with a really innovative nonprofit called Karma Currency. Here’s how Karma Currency works. Let’s say that you are the President of a large bank, and your bank wants to make a major donation to charity. You could just write one big fat check and be done with it. Or you could divide up that contribution among your employees and give each one of them a voucher for Karma Currency. Your employees could then log in to Karma Currency and make a donation on behalf of the company to the charity of their own choice.

So we wondered, then, whether giving employees the opportunity to actively participate in corporate giving may actually increase their own job satisfaction. So to find out, we randomly assigned some employees at a large Australian bank to receive a hundred-dollar voucher for Karma Currency. Some people got it, some people didn’t, so we could look at the impact. What we found was that giving employees the opportunity to give significantly increased their job satisfaction. And I think this is pretty interesting in light of some recent headlines about the very low levels of job satisfaction currently in America. So this suggests that actually enabling people to be generous can provide a sort of surprising route to increasing their own satisfaction.

Now, pushing this idea even further, we wanted to see whether financial generosity might not only improve employees’ job satisfaction but also increase performance within teams. To look at this idea, we examined two very different kinds of teams, pharmaceutical sales teams in Belgium, and dodgeball teams in Canada. So, what we did is we went in to each team and we gave a few people on each team a little bit of money to spend. On some teams, we told everyone, “Okay, just spend this money on yourselves.” On other teams we said, “Alright, we want you to spend this money on your teammates.”

Well, as it turned out, when people had the opportunity to spend money on their teammates, pharmaceutical sales teams sold more drugs and dodgeball teams won more games. So, this suggests that spending money on others may be a good way to go whether you want to change the world, increase your own happiness, or just win a game of dodgeball.

Now, if you go outside today and find that the lovely Camden sunshine has been replaced by a downpour of cash, I would encourage you to go ahead and grab some of it, but think about spending some of it on others. And of course don’t forget to take a little extra time to enjoy your chocolate. Thank you.

Further Reference

Elizabeth Dunn’s web site at University of British Columbia