Gilat Lotan: It’s really great to be here. I’m going to go over a bunch of data points which I think are interesting and might help us take this conversation forward.

So I’m Gilad. I’m chief scientist at the startup called SocialFlow in New York City. And I look at a lot of data in my daily routine. So, we mine the full Twitter firehose, the full Bitly firehose. We build that into our product, but a lot of what I do is try to find out interesting things that we see in the data and tell stories from it.

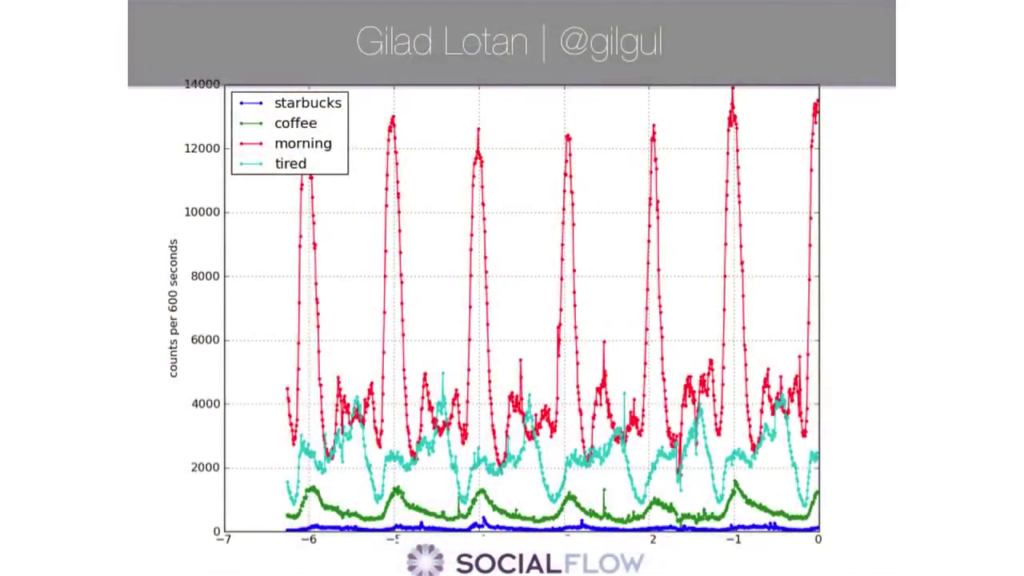

So, lo and behold humanity is fairly consistent. We would mention mornings in the mornings. We get tired sort of towards the evenings. Talk about coffee more frequently in the morning. These are the sort of normal diurnal patterns that we see on Twitter, right. As expected.

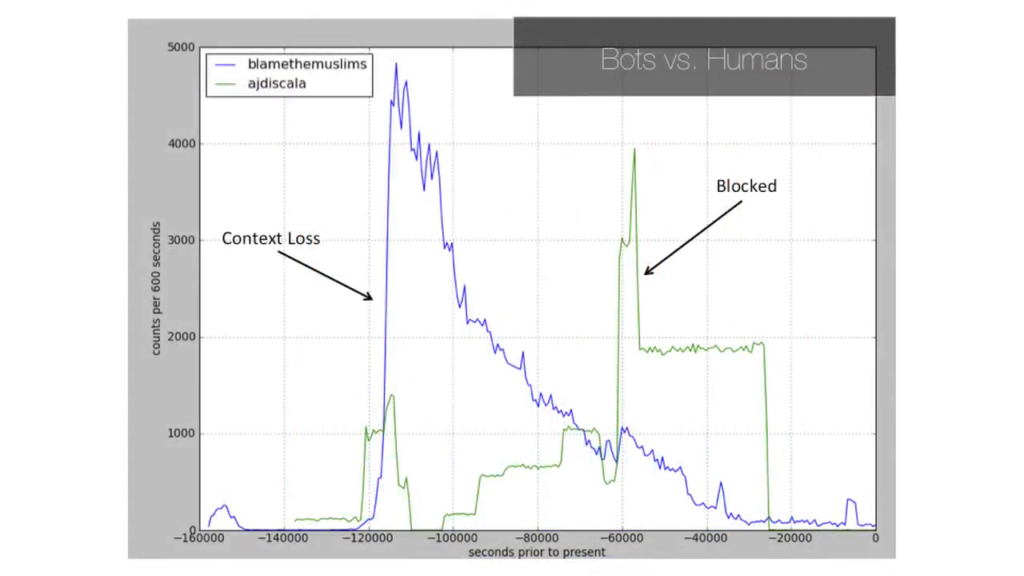

But when interesting events happen and events that are out of the ordinary happen it’s very clear that they happen. So these are two very different trends on Twitter. One is your typical hashtag that goes viral. So in this case it’s #blamethemuslims. Starts very locally in London. It started right after the events in Norway. So instantly, different Muslim organizations were blamed for what happened in Norway. Actually a Muslim Twitter user around London started this hashtag and was saying, “Oh you know, your your clock is broken? Why don’t you blame the Muslims? Oh, your car’s not working? Just blame the Muslims.”

And she and her friends were sort of using the hashtag for snark. It sort of spread locally within their community but died down at night. In the morning, total loss of context, spreads thoroughly on Twitter, becomes globally trending. And then sort of dies down.

Alright. So we see an organic trend. We see it grow. We see loss of context. So that’s interesting. Is that misinformation? It’s people who saw this hashtag and are thinking it’s something very different, right. There are people who got really angry and said how dare Twitter have this as trending? This is not okay. But it started as a joke, a local joke. Spreads and then dies down. That’s totally organic, we see this all the time.

What we see in green is how a spambot network looks like. So you see these steps happen, right. It’s as if someone’s turning a crank. Like, “Okay, add more tweets. Okay 50,000 more tweets. More tweets. Then take them down.” And what happens here, we suspect it sort somehow reached some organic growth. So it sort of started somehow growing in organic traffic. Twitter caught it, shut it down, and then it died. So this stuff, we could clearly see this kind of stuff happening on Twitter just by looking at the dynamics of the levels of data. It’s so easy to tell.

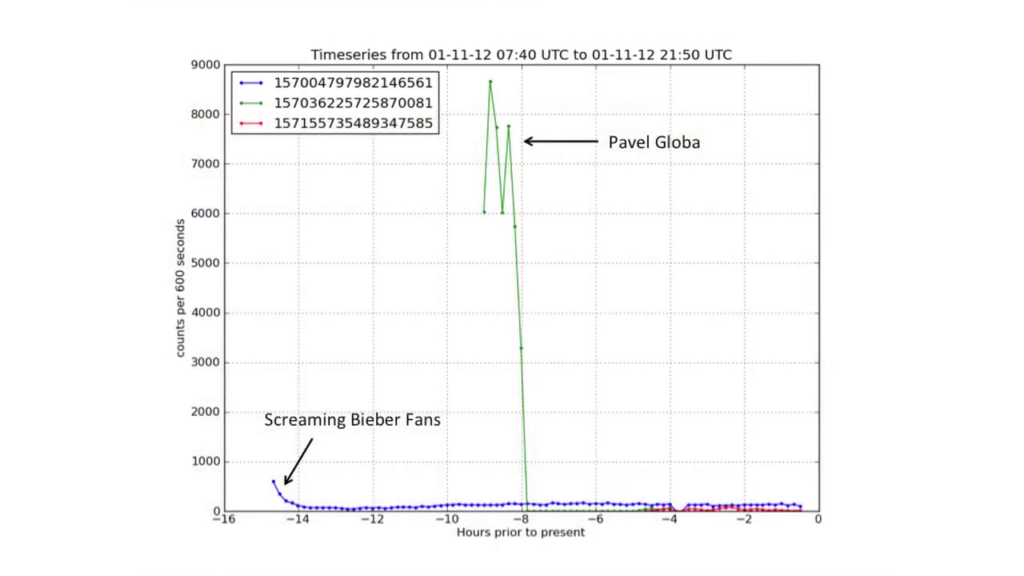

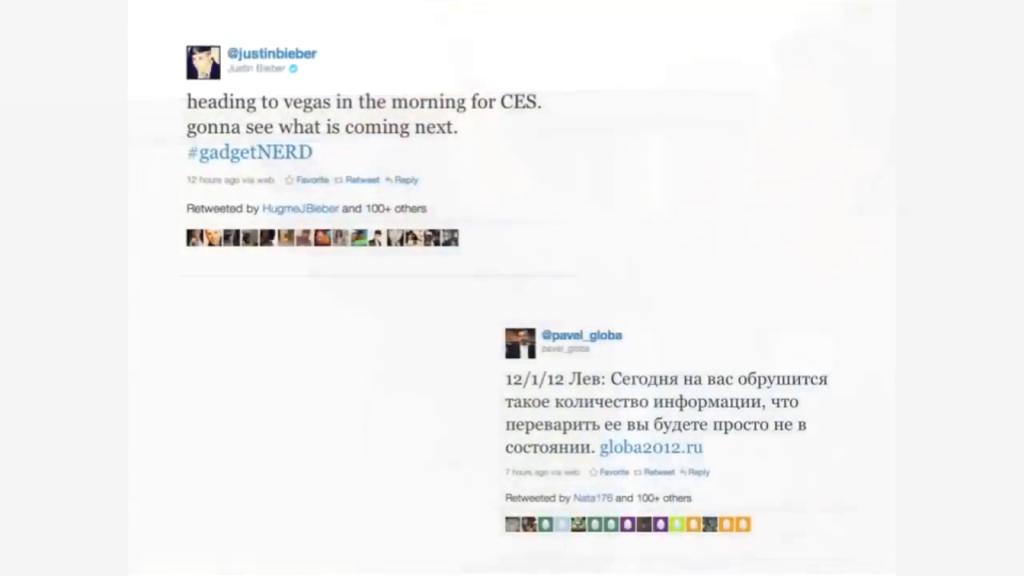

Another thing that we can tell is throughout all these social signals. So we all know Justin Bieber and his screaming fans on Twitter. This is how much traffic he garners, how many retweets he gets, in comparison to Pavel Globa. Who’s probably the most retweeted person on Twitter, thousands and thousands and thousands of retweets. But we never get to see him. Because his content looks something like this, right:

We see lots of eggs, we see sort of— I mean he writes in Russian, he gets a ton of retweets. By the way, he predicted that the Mayans were not right. So 2012, we’re safe. The world is not ending. He’s getting a ton of retreats for that. But obviously the social structure of the network, and the way we sort of build our networks in these spaces means that we don’t get to see a lot of this content because we wouldn’t subscribe to him.

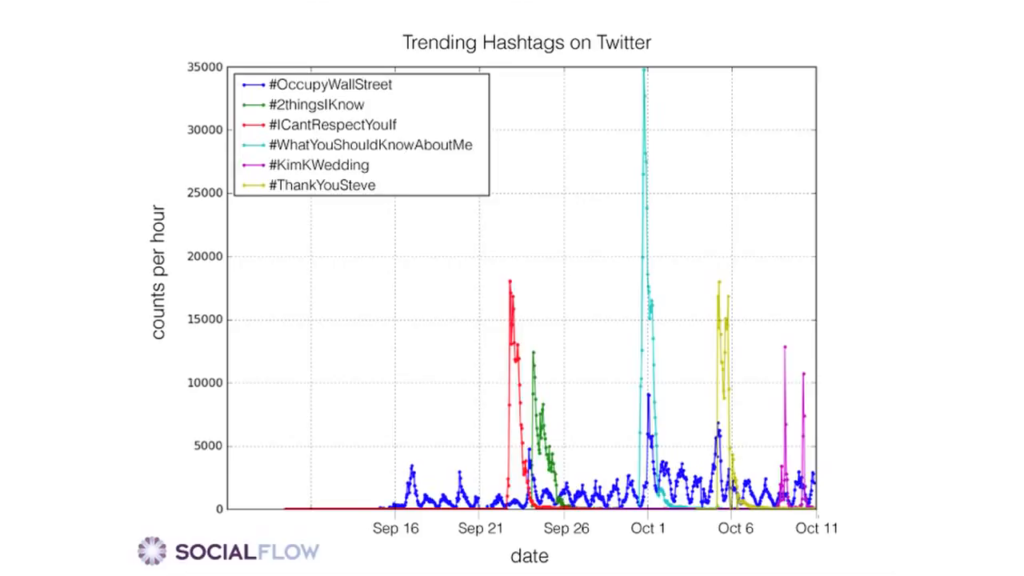

This is another thing that that we can get from looking at data. There’s an analysis that we ran on trending topics on Twitter. If you Google “Occupy Wall Street trending topics” [see further reference links] you’ll see a sort a better explanation for what this means. But in effect, when you actually look at the data and you see what topics are competing with, so levels of attention, Occupy Wall Street in blue is competing with like Kim Kardashian’s wedding, right. Steve Jobs’ death. You see that the way we build these algorithms, the way these algorithms promote certain trends to trending topics means we will never see anything sort of slowly, slowly grows.

This is an interesting example of context-setting, right. Another information flow. This is how the news about Osama bin Laden. So Keith Urban, who used to be Chief of Staff for Donald Rumsfeld wrote, he got off the phone, he’s like, “So I’m told by reputable person they’ve killed Osama bin Laden.” He didn’t have a huge following, he didn’t have a huge network. But he had people who who sort of set his post in context. You know, Jake Sherman for Politico, “Rumsfeld chief says this.” Brian Stelter, The New York Times, also pointed to the fact that he used to be Rumsfeld’s chief. So with without that context-setting we suspect the information wouldn’t have spread as far. That was a case of truthful information that spread, a rumor that spread, really far. This is a case of supposedly false information that spread quite far.

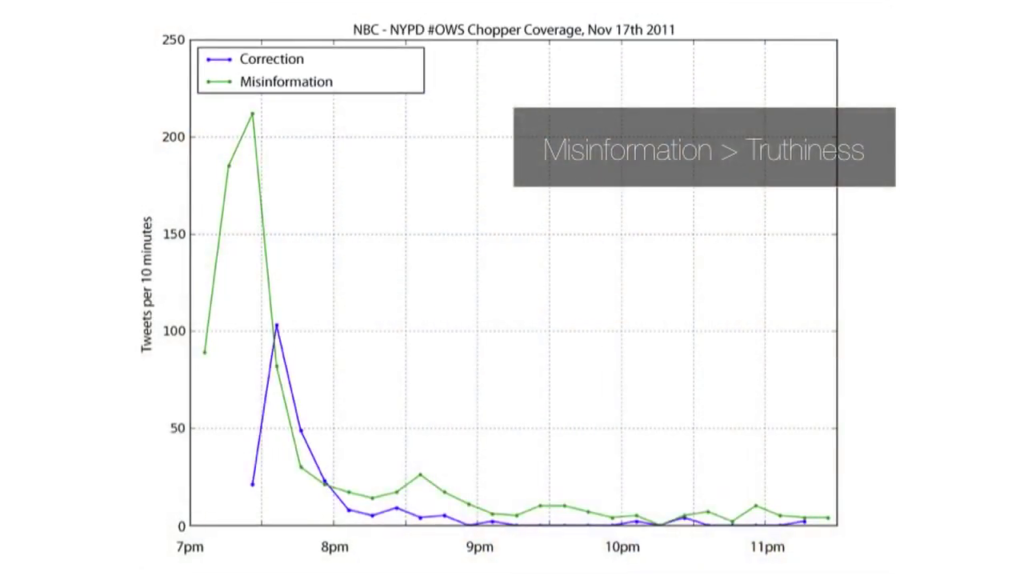

So at the height of Occupy Wall Street, Chopper [4] was supposedly told by New York PD to move, that they’re closing the airspace. So NBC posted this. It garnered a lot of responses. And they had to retract it because New York… It’s still unclear what exactly happened but supposedly New York Police Department said that the pilot misunderstood what they were asking him, etc.

So what we see when we actually look at the traffic, the green is the misinformation. So, there’s substantially more responses to the actual misinformation than the retraction of it, right. But this is not always the case. This is just the case for this specific events, and there are actually all these issues with these events. But the more interesting question that we should be asking is first of all, what other posts about the misinformation went out, right? Not the formal ones from NBC, but also who participated in the misinformation versus the information? And a lot of that we can get from the data. So I think I’m going to stop here because we’re running out of time. And we’ll continue the actual panel. Thank you so much.

Further Reference

Where Lotan suggests searching for “Occupy Wall Street trending topics” it’s likely he was referring to two 2011 pieces at Nieman Lab by Megan Garber: Why hasn’t #OccupyWallStreet trended in New York?, and In which Occupy Wall Street (though not #occupywallstreet) finally trends on Twitter

Truthiness in Digital Media event site