Thank you. I’m very glad to be speaking here today, because food has always been something very very close to my heart since a very young age. I became an orphan when I was seven years old, and that is the time that I learned how to work to put food on my plate. And I was out of school when I was nine years old because I could not afford to go to school in the morning, come back home, work, so I can have maize meal to make our only meal of the day. I left school when I was nine, and when I was ten I was offered to marry a guy who was thirty years my senior so I could have food on my plate.

And so from that background, I understand food as something that can change a lot of the major issues of our time, starting from early childhood marriages, violence against women especially in the part of the world where I come from. And when I refused to get married as a ten year-old, the person who was arranging to marry me off told me, “You have turned down all the help that I offered to give you, and I want you to know that from now on you’re on your own.” And that was me at ten.

When I was eleven years old, I learned about mushrooms, and that was a turning point for me. I learned to farm mushrooms as a young girl of eleven years old, and that was the first time I experienced how to put food on my table in the easiest way than I had been doing before. I was trying to farm. We had a piece of land that belonged to my grandmother who was already over a hundred years old, and I was farming. At the end of each day, all I had was just stalks with no corn on it, and I could not do anything with it.

When I learned to farm mushrooms, I discovered to grow mushrooms you use agricultural waste that is available to all the poor families in any any place we can say this is a struggling country. As long as they practice some form of agriculture, they will have this kind of waste material.

Growing up as an orphan in Sub-Saharan Africa, I was one of the thirty-four million orphans who at one point have to be married off so they can have food on their plate. Or they have to withstand different forms of abuse so they can eat food before they go to bed. In Zimbabwe alone, where we have a population of fourteen million people, 1.5 of that are orphans, and about 3.5 of them, they go to bed hungry.

Now, as a young girl of eleven finding out that by converting agricultural waste, I can purchase food, I set out to understanding deeply about the art of cultivating mushrooms and simplifying it so we can reach as many people as possible. And for me, my commitment was to reach young orphans who were going through the same situation like I had to go through as a young girl.

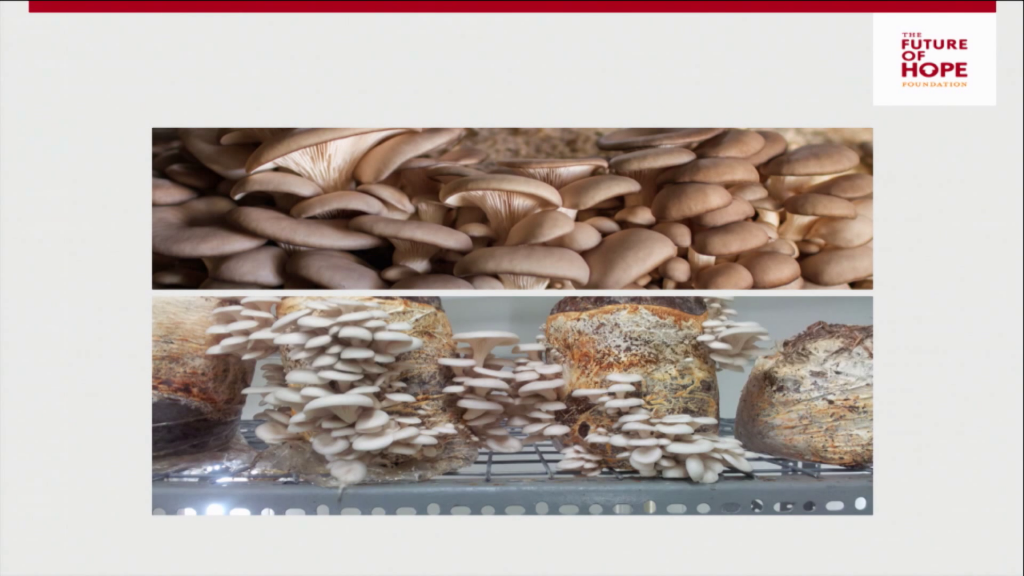

Mushrooms are very high in protein. They also have a bit of carbohydrate, and they have a lot essential amino acids, as well. They are very healthy as a food, but they also work as a medicine. And I went as a young girl of twelve to a university where I spent time learning more about mushrooms, learning how I can grow mushrooms from different kinds of waste material. And this is from corn stalks, from chicken manure, from cow dung, but also coffee.

That is me when I was starting to grow mushrooms as a young girl, and without any understanding of science. And of course I decided I would simplify and travel to different places in the world and adjust the growing spaces. Mushrooms are growing in very small space, but most of the time it’s made to be a sterile environment where you have to do a lot of work sterilizing everything. And I figured out a model of how to simplify that so village women in Zimbabwe can do it.

On one square meter of land, you can produce seventy-five kilograms of mushrooms in three months. And this is a lot of food, especially when you consider that one kilogram of these mushrooms can be sold for seven American dollars in a country where a lot of the time, people who are suffering with HIV and AIDS, they don’t even get a dollar to get a supply of their medication for a month. Young girls who have an opportunity to go to school, they have to stop going to school when they’re having their period because they can’t buy sanitary pads for when they have their period. And in some cases, they were actually using cow dung because they don’t have anything else to use.

So for me, it was important to simplify that. So we are growing mushrooms in different structures that can be built using what the people have available. And for me, this defines the future of food. Empowering people, capacitating people, to use what they have, where they are, to produce food. Learning from their cultural practices. I was harvesting mushrooms in the forest with my grandmother as a young girl of seven. So cultivating mushrooms is really building on a tradition that has been there for a long time and only now lost in the name of “civilization.”

So we are working now with groups of women in different places, children and men together, teaching them how to use the waste materials that they have to grow mushrooms. And one would wonder… I mean, yes you grow seventy-five kilograms of mushrooms in a square meter. What amount of waste, and how does that work? So, if you have one hundred kilograms of waste, you get fifty kilograms of mushrooms. And then you have a waste material that you can use as a fertilizer for growing other food.

So this is the work that we’re doing with local communities. Awakening individual persons with the little resources that they have, that they can contribute towards the future of food production. And what I believe in personally is that food production has to belong in the hands of everyone. Everyone has to own the means of producing their own food. And everything, every system that we develop going forward in food production has to be adjusted so they can feed in the local practices of every place in question.

And we need to build collaborations that help us to understand beyond just what we do in our little circle. Because the work that I have done with mushrooms started as a young girl who wanted to put food on her plate, to helping communities around me. But also to impacting the lives of others globally, where we train entrepreneurs through converting coffee, the waste from coffee that you have in your tea, into mushrooms. Because, for all the coffee that’s produced in the world, what what we drink is only 0.2% of what is produced in total. And the rest, 99%, is thrown away. And we take that waste material first on the farm, convert it into mushrooms, and then we go into cafes. We have this happening here in the USA in San Francisco, where I train them to convert waste material from coffee, from the cafes, from the Starbucks, into mushrooms. And we have adjusted the method of production so it can be implemented in different places. In the basement of this place now, we can turn it into a mushroom house. And for us, this is something that is important.

So in short, I would say the future of food for me means collaborations that matter. And this is a bit what’s between me and the people from MAD, where I grow food and I see what they do as chefs, and we actually plan to have a big event in Zimbabwe where we will produce food and we will work on processing that food together this year. And these collaborations are what is going to change, and everyone taking responsibility, is going to redefine and reshape the future of food, we all act responsibly to change it.

Thank you.

Further Reference

MAD has been doing some ongoing work with Chido’s organization The Future of Hope.

Overview page for the MAD at the World Bank: “The Future of Food” event.