I want to start my presentation with the humble light bulb. So, of the first commercially-available electric light bulbs came off the production line at the Edison Electric Light Company in 1880. And commercial light bulbs as we know them were pretty good at the time. They were slightly brighter than existing technologies, mostly candles and lanterns. Certainly they were a lot more expensive at the time.

But they had one really chief kind of a property, and that was instant, on demand lighting. So, the fact that you could go up to a light switch, turn it on, and light would sort of pour forth was really an incredible feat at the time. And it certainly changed society on a global scale. It changed our work practices, how we socialize, when we go to sleep, and many other aspects of our lives.

But what’s interesting about the light bulb is that the technology has changed over the years. Certainly we’ve gone from sort of incandescents to compact fluorescents and LEDs. So we know the technology’s changed over about a hundred and forty years. But the function really hasn’t changed. A light bulb from Edison’s era to now, you flip the switch, light comes out, helps you read a book or make dinner. The function really hasn’t changed, and that’s really quite remarkable in such a long history.

And it’s even more remarkable when you think about how much technology has changed in the past century, especially as it relates to computing technology. So, what we’re trying to think about now is, take the sort of venerable light bulb and recast it as a computational appliance. So, how do we take something that’s been so remarkably successful and infuse it with computational abilities? And that’s what we’re working on at CMU.

So, what do I mean by this? Well, if you have a light bulb on one side, you turn it on, light comes out. We’re familiar with this technique. [It] helps you read the paper sitting on the desk. An info bulb is similar; light also comes out. But instead of just being kind of ordinary light, it can also be structured light. So it can actually render information and interactivity onto a surface.

So, to give you a more concrete example, you might have an office desk lamp. If you could unscrew that incandescent bulb, throw it away, put in your new info bulb, it could actually sense and read everything that’s on that surface or happening on the table. So, not only read the content on the table and what objects are present, but also be able to track your finger touches and your gaze and so on.

So you might have an array of documents sitting on that table surface, and it can actually understand that content, give you sort of Google searchability right on your paper documents, have Wikipedia articles linked off. It knows all your email so it can tag maybe experts that you’ve corresponded with in the past. It’ll digitize your handwriting, check your math, and all these different aspects that physically augment the environment around us.

You can imagine other contexts, for example may be recessed light bulbs in the kitchen or the hanging lights here. These could also be replaced with something like an info bulb, and it would turn this kitchen setting essentially into a computing platform. It could understand what kind of ingredients that you’re preparing. It could automatically start timers when you start boiling a pot of water, and so on.

Now, a really successful paradigm we want to borrow is smartphones. So, what make smartphones really amazing— Actually the hardware is nifty, but apps are really will make them indispensable. And so what’s the notion of sort of taking this notion of an app market and having it on the world? So, what sort of apps would you want to have running on your kitchen countertops, or running on the surface of your desk? And how do we leverage that notion?

And this starts to sort of change how we think about computing as we know it today. Right now when we think about embedding computation in the world, it means sort of sprinkling little screens everywhere. You might have a little Nest, you might have a smartphone, a smartwatch. We really want to embed computation in the world, and I think the way to do that is by projecting directly onto it and augmenting the physical materials.

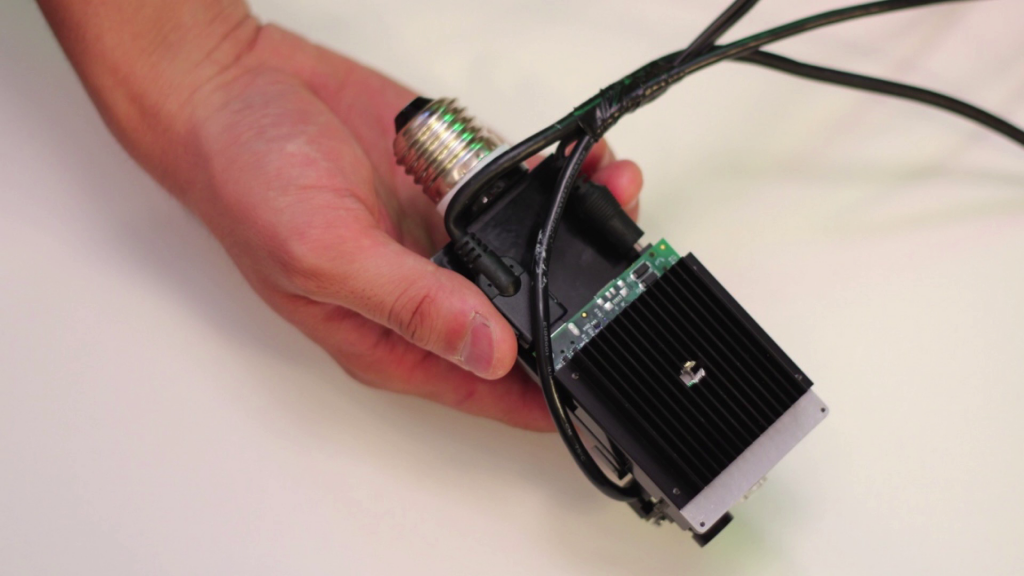

So, this isn’t science fiction. We actually have this working at Carnegie Mellon. This is actually an older prototype from about five years ago. And you can see the hardware’s not anything particularly special. It’s an off-the-shelf digital projector, and we’ve literally glued on top of that a direct connect camera, which is a depth camera. And this allowed us to start prototyping the software, which is much more important.

So here is actually one of my PhD students interacting with the system—there’s one of these systems attached to the ceiling—and he’s literally able to paint interactivity onto the walls of his office. His office, for all practical purposes, is a computing platform, it is a computer. And In this case he’s written a little app that lets him set an away message for his office. So if he’s working or if he’s in a meeting and so on.

Now, obviously technology has evolved even in the last five years, and so we’ve been able to produce an even smaller prototype. So, here what you see, at the bottom there’s a projector, underneath there there’s another depth camera. There’s a computing board to do the processing. And more importantly is we have that lightbulb screw base at the top. So this is something that just in a few years you’ll be able to actually have a self-contained unit that you can fit into a regular fixture.

So, here’s that newer system working now. We can launch applications on tables. There’s a nifty feature you can see where we can actually physically snap virtual interfaces to physical objects, in this case a number keypad to our laptop and it sends the input to the laptop. And then here’s another application, a GMail calendar. And we can scroll through our apps and resize the window. So very much like a desktop computer.

So, back to sort of our notion of light bulbs. Light bulbs have been so remarkably successful because they’ve literally blended into the background. We’re not overwhelmed by high technology. We flip that switch and we don’t really think about the infrastructure that makes that happen. And I think the same will be true for computing in the future. Future generations will think of computing as a utility, just embedded into out environment and information and interactivity will be just available on demand, like lighting was a hundred years ago.

Thank you.

Further Reference

Chris Harrison’s home page.

The Future Interfaces Group at Carnegie Mellon University.