I feel happy to say that it is (I think like everyone else who’s stood on this stage) a profound privilege and a pleasure to be here. It’s always kind of fun as an Australian to be in New Zealand. I will say this is a much better experience for me than the last time I was here speaking, when I was the warm-up act for Sir Richard Hadlee. For the Americans in the room, he’s a cricketer. For the Australians in the room, he’s an honored enemy. For all of you, he was a hero and I was in the way. This, much better.

I know the title of this talk is kind of cheeky, and it clearly requires just a little bit of unpacking. It actually comes from a soliloquy from a television show that I love unabashedly. The show is called Penny Dreadful. I’m sure some of you might’ve seen it. Set in 19th century London, it’s a Gothic horror tale. It is replete with characters from fiction and fantasy and in some ways the imagination of John Logan, who is clearly demented in ways that I love. It draws on all these characters and, in the very second episode, Dr. Frankenstein, Victor himself, appears, is creating another monster. And monster #1 turns up, kills monster #2, and in a fit of rage delivers this extraordinary soliloquy, and I just want to read a little bit of it, because for me it is kind of where this talk takes off. Monster to Frankenstein:

I’m not the creation of an antique pastoral world. I am modernity personified. Didn’t you know what you were creating was the modern age? Did you really imagine that your modern creation would hold to the value of Keats and Wordsworth? We are men of iron and mechanization. We are steam engines and turbines. Were you really so naïve to imagine that we would see eternity in a daffodil?

Penny Dreadful, “Séance”

Of course, here we’re playing on a familiar idea that technology is apart from poetry. That technology is not art, that it’s not love. Of course we’re riffing on two poems here by Keats and Wordsworth, the poem beauty travels and the poem about clouds, daffodils here in many ways [symbolizing] many things.

But in this talk I want to suggest that it’s never quite as simple as to say there is technology and there is art. That there is technology and there is culture. Clearly these things have always been in dialogue and are still. So this means this is a story about art and technology. It’s also a story in which I am acutely aware I am neither an artist nor a technologist, so it’s a little bit cheeky.

I am in fact the child of an anthropologist, a child of the Pacific and the Southern Hemisphere. I spent my childhood on my mother’s field sites, and I spent my formative years living in indigenous communities in Central and Northern Australia at a time when people still remembered what their country was like before cattle and white fellas and fences, not always in that order. It was a long journey from those communities to Silicon Valley where I now live and work. Somewhere along the way, I found anthropology. I followed in my mother’s footsteps. I did my undergraduate degree on the East Coast of the United States, and my graduate training at Stanford. I was hanging around Stanford in the late 1990s, teaching anthropology and loving the experience of having a classroom, when in true Australian fashion (and possibly, I suspect, New Zealand fashion) I met a man in a bar in Palo Alto, and he changed my life.

Now, in America I have to point out that didn’t mean I married him. It also didn’t mean I had sex with him. And actually I didn’t let him buy me drinks, which was probably not a good plan because he did have more money than I did. I was, again, a professor. He was in Silicon Valley. But he asked me what was it would turn out an incredibly important question, because he said to me what did I do. And I said I was an anthropologist. He said, “What’s that?” I said someone who studies culture, and he said, “What do you do with that?” I said I teach, and he went, “That’s nice.”

Okay, good.

He said, “Couldn’t you do more?” And I’m thinking I’m a tenure track professor at Stanford University. This is as good as it gets for people like me. And I thought, “Well I’m done with you.” So I left. And because my mother as well as being an anthropologist is an eminently sensible woman, she told me never to give my number to strange men in bars, so I hadn’t. So when he called me the next morning at my house, this was odd. Because we are talking about 1998, so before Frank’s modem noises, or right on the edge of it. Certainly before a white box on the Internet, or LinkedIn, or Facebook, or really anything else. There was no Google into which he could’ve typed “redheaded Australian anthropologist” and my name would’ve popped up. Truthfully, if you do it now, my name is the first search item, which I’m kind of proud of, in a very perverse way.

But in 1998, there was nothing, and he did it the old-fashioned way. He called every anthropology department in the Bay Area looking for a redheaded Australian. The secretary of the Stanford anthropology department said, “Ooh, do you mean Genevieve? Would you like her home phone number?” I’m oddly grateful, but at the time I was very annoyed.

So Bob calls me. Bob says, “You seem interesting.”

I’m like, “You’re not.”

He’s like, “No no no.” And then he said magic words that will ring true for some of you still. He said, “I’ll buy you lunch.” Then I realized I wasn’t that far out of graduate school that I wouldn’t still do things for free food.

So Frank introduces me around the valley. He was an extraordinary mentor. He introduces me to the people at Intel. Intel at that point are hiring, which I didn’t know. I also didn’t know that they were growing a small team of social scientists, and that they desperately needed a woman, because they had six men and they realized that was possibly a problem.

I didn’t know any of these things when I rocked up for my interview. I aced the interview, surprisingly because I was kind of belligerent. And at the end of the interview process, you’ll be happy to know Janet, they asked me, “Is there anything else we need to know about you?”

And I said, “Well I’m kind of a radical feminist and an unreconstructed Neo-Marxist.” I was 29 and I didn’t really want the job, I hasten to add.

And the nice men with whom I now work looked at me and said, “Will we like that?”

To which I said very honestly, “I think the first six months will be rocky.”

So I get to Intel. My new boss sits me down (Who is astonishingly a woman reporting to a woman. Little did I realize how rare this would be) and says, “Great, you’re here. We’re very excited. We need your help with two things.”

I’m like, “Good, and these would be what?”

My new boss says, “Well, thing number one we need your help with is women.”

Now, I’m fresh out of the university system, so I ask the obvious next question, “Which women?”

My new boss says, “All women.”

“So you need my help with all 3.2 billion women.”

“Yes” says my boss.

I’m like, “…okay.”

So in my notebook of the day, I write down “Women all.” And underline the “all” a lot. And try to imagine what is the project you will do to explain why “women all” is not a meaningful category, and then some insight that will be useful about “women all” that will be useful to a semiconductor manufacturer. ‘Kind of problem that as a researcher can make you very happy.

But then remembered this new boss had said two things. And if thing #1 is “Women all” it is terrifying to contemplate what #2 might be. I secretly hoped she would say “men,” because that’d round out the equation.

But no, this new boss said that Intel had an ROW problem. And I’m like, what’s that?

She said, “Rest of World.”

And you know at this point I know I’m from Rest of World, but I ask anyway because I’m a good researcher. I’m like, “And where’s ‘world’ in this equation?”

She says, “That’s America.”

“Okay, so to recap you need me to study women, and everyone who doesn’t live in America.”

She said, “Yes.”

And I said, “Good.”

And I went back to my desk. I thought for a long time about what the job would be that that was the brief. And I realized two things. One was that that was the best opportunity I was ever going to have in my entire life. That being offered the job described “women all and everyone else” meant that my job was to talk about all the people that weren’t in the building to all the people that were. And that my job was ultimately and always going to be about how did I bring the stories from the rest of the world into the building, and use them to shape next-generation technology development and innovation.

That has to be, and still is to this day, about the best gig you can ever have. Because it’s the business of telling stories. As Kim said this morning, it’s what I get to do. I get to talk about stories. I get to do them based on what people care about, what pisses them off, what frustrates them, what they love, what they desire, what they hope for themselves, their kids, their families, their communities, even their countries.

And on a good day I get to use that to shape the values we talk about and the values we don’t. And the products that we make as a result of that. On a bad day, I just spend a lot of time saying, “Where are the women?” Because you have to. But what that also means is that I’m in the business of thinking about the future, of thinking about technology, of thinking about the stories we tell about technology. So I have had the extraordinary privilege to sit in the front row for the last 18 hours and listen to people tell some of the most extraordinary stories, and I want to add just my own small little one here for all of you.

Sometimes we tell aren’t about what’s on the screen. They’re not about technology per se. They about our relationships to technology, and those stories are profoundly revealing and important, and they’re rooted not just in the present and the future, but also in our past. I want to unpack a set of those stories for you, because I think they’re really important for how we think about the future.

I ran across this video on YouTube about two and a half years ago.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=18UmoIu8lII

This is the best 47 seconds of video on the Internet. I’m sorry, the cat and the donkey on the boat notwithstanding, this is really it. Because in this 47 second video, someone has staged a conversation between Furby and the first generation of Siri. You all remember Furbys, right? Furby were small, digital, squealed a lot, ears [flapped], eyelashes fluttered. They went, “Ah ah ah ah ah!” Yes? [audience agrees] Okay, good. You’re all just looking at me. I know they got to New Zealand because they’re on the Qantas instruction of things you can’t take on a plane, so they must’ve gotten here.

So the Furby goes [squeaking noises]. And Siri goes, “I cannot find Graham in your address book.”

And the [Furby] goes [squeaking noises].

“Would you like me to look up Shell Oil?”

It’s delightful. Part of why it is fabulous is these are the stirrings of digital life. These are things that are digital having, effectively, a moment of coming to life. The Furby came to life because it talked and danced, and it did it on its own mildly hysterical cadence. Sometimes, unknowable, frequently disturbing.

Siri is two generations later of a digital thing coming to life. It doesn’t just speak, it listens. It doesn’t just listen, it has the promise that it might have a relationship with you, that it might be doing things in the background on your behalf. All of those promises are imperfect, but they say something really interesting about our desires and our aspirations, and our constant fascination with what it means to bring things to life. Of what is it about our mild ambivalence about robots and artificial intelligence and drones, and why it is that we thing that the Roomba is funny and also troubling.

I hasten to add here when people ask me about the robot uprising, I will tell you the first place it is going to come is with Roombas. There are ten million of them in circulation, literally and figuratively. Most of them without LEDs. And you know, you think that the robot uprising is going to be big. No, it’s going to be down on the floor, disconnecting your wireless router, which is a very different peril.

So why is it that these objects held such a fascination for us? What’s going on here? Part of what’s going on is that in human cultures over I would say a millennium, we have been fascinated with and those cultures are riven through with the stories of things coming to life. All the original origin stories are about someone making things come to life, whether it’s the gods here, whether it is the creative figures who were in the culture that I grew up in, whether it is the Greek and Roman and Egyptian gods, things were brought to life and given purpose and set forth on the planet. All of the major world religions turn on stories of things being made to come to life. Of bringing life into existence.

By the time you get into the last thousand years, those stories get a little more complicated. The last thousand years haven’t just been stories about gods bringing things to life, but about people trying to do it, too. Whether it is the alchemists of the medieval age. We know alchemy stories because they’re mostly about spinning straw into gold, but alchemists in Asia and in Europe were also fascinated with the idea of making things come to life. Their entire obsessions with homunculi was about making little tiny people and seeing if you could do it.

There were stories that came through literature that were about making things come to life. Those stories sit right on the edges of religion and art and literature. Probably the most famous one, and the one that is most important to the story of robots is the story about Golem. Jewish Kabbalistic story, first appears in oral traditions at least a thousand years ago. It first starts to be written down about five hundred years ago. The most instantiation it is a story of the rabbis of Prague creating a figure out of the mud in the riverbank and bringing it to life to protect the Jewish enclave against the perditions of an angry Catholic king. This golem figure, huge, two meters big, made of mud, mostly unshapen, is breathed into existence with the word of God slammed into its forehead, comes to life and protects the Jewish enclave. Protects them from violence, protects them from anti-Semitism, protects from all kinds of things.

But the story of the golem is also a story of what it means to have men bring something to life. Because this golem has to have a particular set of purposes. It can only do sacred acts. It cannot do menial tasks. When the rabbis wife realizes that she has a body at her disposal, she attempts to make it carry water from the river. (Free labor. Maybe you would do this.) Of course the golem doesn’t know when to stop, fills the basement with water, and eventually floods the house. The moral here is of course that life can only be created under certain circumstances. The decommissioning, for want of a better word, the taking away of life from the golem and its decomposition again is also a story about how you stop life. The pieces of this golem are said to still be in one of the synagogues in Prague, waiting to be brought back to life when danger arises again.

This story should be familiar to us because it runs through our history in many other forms, and I’ll touch on them in a minute. But remember the last time this story has its origin points is the 1500s. By the 1700s, we were already in the place where we could start to find pieces of technology that let you make things animated. There weren’t just stories of animation, it was literally possible.

All these things start to happen in the 1700s: experiments with magnetism, electricity, with mechanical pieces, and suddenly things can come to life. The consequences of this are extraordinary and ripple through to the current moment.

The first set of them are automatons. Here’s this incredible technology for making time, but one of the things about making time was that you could make things move, and they moved on their own. Once you wound them up, they kept going. Not quite perpetual motion, but they’d at least get across the stage; They’d do something. Starting in the 1600s through the 17- and early 1800s, all across Europe and indeed into Asia, there were people who were fascinated by what you could make if you could take the watches apart and use those pieces for something else. Think of it as one of the original hacks, because here you were taking this collection of pieces and doing something interesting and unexpected with it.

There were a number of people who were extraordinarily good at this, but one man in particular changes the game in the middle of the 1700s because he goes from making abstract things that just did something, a hand moved, a small child that danced, to becoming deeply obsessed with verissimilitude, with simulacra, the thing that looked real. His name was Jacques de Vaucanson. He was from France. He goes on to have many other lives, but the most important one is in this moment of time when he becomes convinced that you should be able to make things look life-like.

His first attempt at this is a hand that plays a flute. Has bellows, has hand, has flute. He goes through several iterations and discovers that this thing just doesn’t sound right, and he finally realizes it’s because the hands that he has made are metal, striking the keys on the flute, and it’s not the right sound. He gloves the hand in skin (I hasten to add, sheepskin, just in case you worry.) and plays the flute and he suddenly realizes he’s cracked the code. This things seems real. The courts are kind of fascinated by this thing that sounds like a real flute. It doesn’t sound like it’s mechanical.

For his next and most famous automaton, he creates a duck. Now, those of us who grew up with ducks, this is not so sexy. I was talking about Vaucanson and his duck in Silicon Valley recently to a slightly smaller crowd than this, and I realized that no one knew what a duck was. This is a very odd moment when you realize in a room of 350 people, only two of them had seen a duck. I’m assuming most of you have seen ducks, so I do not need to give you the Duck 101 primer. But let’s imagine duck-sized.

Vaucanson decides he is going to make a duck. Because, as it turns out in 1736 in France most people had ducks, he is competing against good duck knowledge. So, high-barter duckiness. Number one thing with a duck, you know it needs to walk properly, so foot over foot, what we would know as waddling. So this duck waddles; 400 mechanical pieces so the duck waddles. Pretty nifty. Ducks eat, we know this, so the duck has a beak and it clacks because duck beaks should clack. This is good. Again he’s worked out how to make the duck do that; that’s pretty fabulous.

But really the thing about this duck that is quite remarkable is this duck could eat. So the beak went like this [opens and closes hand] but you could stick food in it. And he actually worked out how to make a digestive tract. Rapid prototyping here: first tract he made with metal and it rusted, because he had to put water in it so it gurgled. He becomes the first man to do something with vulcanized rubber and creates a rubber digestive tract. So now this duck will walk up to Mike, who will feed it, it will digest (gurgle, gurgle, gurgle, gurgle, gurgle), and this duck does one more thing. I’m willing to bet you can guess what it is.

The best bit, of course, is in 1736 he couldn’t actually work out how to genuinely fake digestion, so this duck had pre-cached shit in it. Next time you think about interns, imagine that there was some intern who had to go collect duck poo and stick it in the bum. And that was its job.

So this duck wandered across the stages of Europe, waddle waddle waddle, chomp chomp chomp, food food food, shit shit shit. It was spectacular. No one had seen anything like it. Voltaire declared that without this duck there was no glory for France. I’ve always thought that said more about Voltaire and France than it might’ve said about this duck, nonetheless this duck was seen as being quite spectacular. And changes the game, because what it suggests is we could use mechanical things to make something come to life. Even if only across as stage. Not very far, but far enough to be interesting. And far enough that a whole lot of other people wanted to make automatons that were just like this. That were real. That suggested lifelikeness.

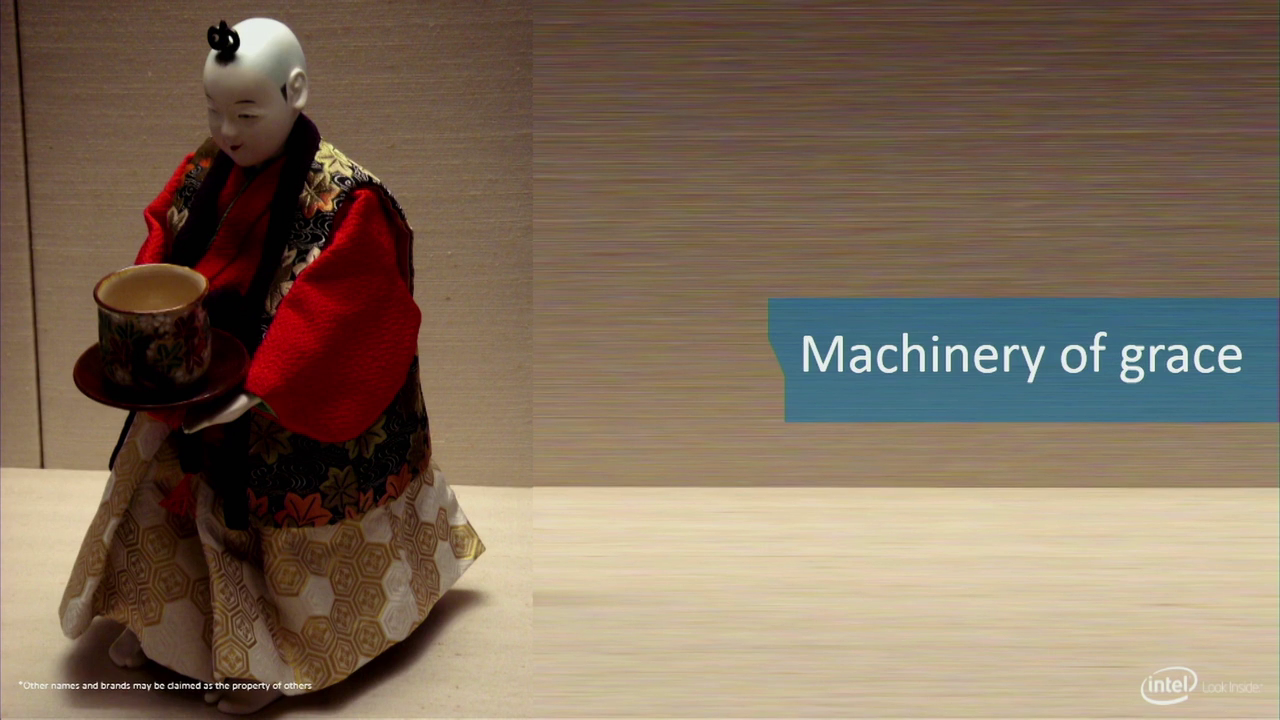

But what that meant looked different in different places. The very same technology, the very same watches from the very same clock pieces, traveled to Tokyo. And in the hands of a man sometimes described as the Edison of the Edo Court, a man named Tanaka, he took the watch pieces and made something completely different. He didn’t make automata, he made karakuri, which is what this one is here. It’s a teacup karakuri, about this big. [holds hands at about doll-size] So not lifelike, or life-sized, frankly. Its special trick was that you put tea in it, and it ran across the tabletop. When you took the teacup out of its hand, it bowed, and ran away again. So not mimicking real life, but importantly participating in what was a hugely critical cultural ritual in Japan at the time, which is the tea ceremony.

So here is the technology wound up to deliver an experience that is culturally appropriate, not about making things lifelike, which was the European obsession, but about beauty and grace. Same technology down to literally the parts, completely different notion of what it needed to do and why it might need to do it.

Of course, all of that is happening but these other things are happening, too, which is that people are now starting to think about, what are going to be the consequences of bringing things to life. If you can see an automaton, what comes next?

There’s a young woman who we all know. Her mother was probably the first suffragette. Her father was a labor historian and writer. She grew up watching the Luddites in England, going to the Egyptian hall and seeing automata and seeing all kinds of new technologies on display. Her boyfriend of the time, who was married to someone else (little complicated) was attempting to seduce and woo her through poetry and reading. One of the first things he read her was an English translation of a Grimm Brothers story about the golem. And in the summer of 1816, she ran off with him to Europe, as you might.

So, she ran off with him to Europe with his best friend, his best friend’s doctor, and her half-sister, who was trying to race off with the best friend. If this sounds a bit like the Daily Mail, it really was, because frankly this stuff was being covered in the second page of the Times of London because the best friend is of course Byron. And you know, Byron got around. Best epitaph ever, right? Byron, described by his spurned lover Charlotte Lamb as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Which in 1816 sounds delightfully modern.

They were at a dinner party, as you might be. Byron declares that he is frightfully, frightfully bored in the way only the English aristocracy can, and declares that everyone must immediately write him a story to shock him. Three tropes get invented that night: the vampire stories, the zombie stories, and Frankenstein, which is of course the story about electricity being used to bring someone to life, to bring a body to life, to animate a corpse and make it human, or at least an attempt at human. And it is the ultimate, in some ways, encapsulation of the morals of the golem story and a whole series of others.

Science replaces religion, the word of God is replaced by electricity, but what you do is bring something to life, boom, and there it is. Of course, Frankenstein has been in print continuously since 1818. It’s been in movies and television and it is a story that has seeped its way into our unconscious and into our psyches. And it keeps ticking on as this story about what might go wrong, and about how we might think about why it is that bringing things to life is scary.

Of course that didn’t stop people bringing things to life using electricity. Well into the late 1800s, people were desperately trying to work out how to use steam engines and electricity to make these things that were early robots, walking men basically. Huge things, steam engine behind them, attempting to make them come to life and walk. Turns out to be a really huge problem. Goes on for a long time. People spend a long time obsessing about it. No one ever cracks the code.

And frankly all of that technology gets pivoted between 1914 and 1918 by World War I, when suddenly a whole lot of technology that looked like technology of science and optimizing and production becomes technology of destruction and death, and mass production becomes mass death. A whole lot of technologies that appeared to be of one character are portrayed and experienced very differently.

A whole lot of social reformation comes out of this moment. You come out of 1918 and the conversations in Europe, and indeed in places like New Zealand and Australia, were conversations about new forms of governance, new forms of democracy, new forms of social capital. Whether it was about the suffragettes, the Utopian movement, whether it was bout different ways of thinking about emancipation, all of that technology generated a very different conversation.

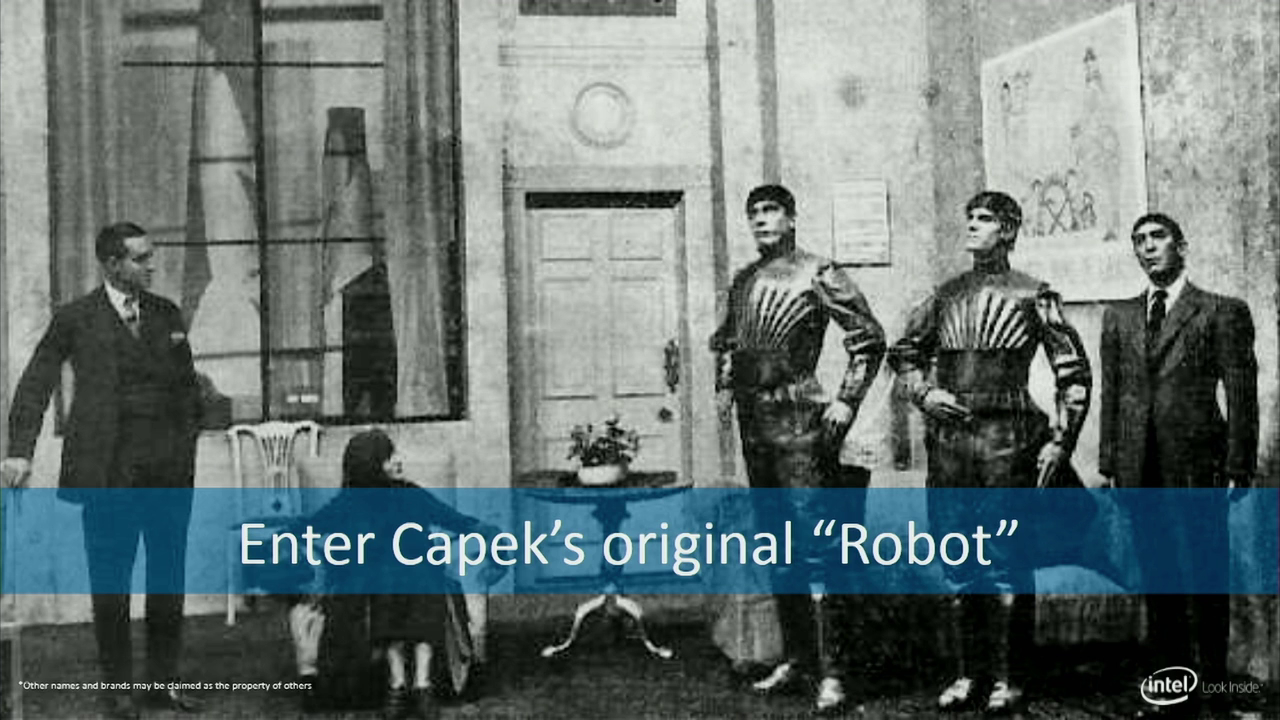

That conversation influenced a young playwright in Prague by the name of Karel Čapek. He couldn’t go to World War I because he had a medical condition, but he watched his friends go, and he watched his friends die, and he watched his country utterly transformed by this. He started to think about the machinery and about the consequences of the war, and he wrote a play. The play premiered in Prague in January 1921. It was called Rossum’s Universal Robots, and it is the very first time the word “robot” appears in circulation, because the word “robot” is a word of art, not a word of technology. It’s a word invented by a playwright from a word in Czechoslovakian that means “drudge or serf.” A word about pain and class relations.

In this play, which will sound deeply familiar to you, there is a robot maker named Rossum. Rossum produces a whole series of robots that can only live 20 years. They have to do productive tasks, and after a couple of generations, they get really shitted off by the fact they’re not happy and they don’t have souls, and they come back to him and demand to be given both. “We’d like a soul and we’d like to not have to die after 20 years.” Should sound vaguely familiar as a plotline. This would be the plotline of Blade Runner, among other things.

In theory, a play that premiers in January 1921 in Prague, in Czechoslovakian, should probably stay there. Not because it doesn’t have anything to offer to the world, but the geo-capital politics of it all are just that plays in plays in Prague in 1921 don’t go global. Except that this play did. January 1921, Prague. October 1922, Broadway. March 1923, the West End. January 1924, Tokyo. Sydney…1935. New Zealand, I can find no record, for which I am sorry.

This play circles the planet incredibly quickly. It’s translated into English, clearly. It premiers in New York to great acclaim. The New York Times doesn’t love it. They compare it to Frankenstein and say it doesn’t raise goosebumps. The Mail thinks it’s excellent and will be a real winner. Tells you something right there.

Part of why this play resonates, though, is that it’s tapping into all these earlier stories. It’s tapping into the story of golem, it’s tapping into the story of Frankenstein, it is naming an entire new form of technology and giving it a narrative, giving it a face. It turns out this play is the first play to appear on the BBC Radio as science fiction. It’s the first piece of televised science fiction on BBC Television. It has this incredible resonance, and it never goes away. For a brief moment there, the robot is a thing of literature. It is a story. It is a human-metallic perfect beautiful object searching for a soul.

But that doesn’t last, because in 1928 an engineer in Britain decides he’s going to make his own robot. His name was Richards. He was the head of the British motor engineer’s society, and he was holding an annual conference in 1928. He invited the Duke of York, the Duke of York said no, and he said, “Fine, I’ll build a robot.” I come from a family that has problems with the royals. I can understand this as an approach.

This is Eric. Eric is 1.8 meters high, he weighs about 60 kilos. He is made of aluminium. He has a 20-volt battery underneath his feet. He has bright blue eyes. He has “RUR” emblazoned on his chest. Rossum Universal Robot, just in case you missed the point. And he bows, a lot, because he’s really polite. He opens the [conference] of the engineering society in the Royal Horticultural Pavilion to great acclaim. Everyone’s like, “Look, a robot! Very cool.” So people kinda go “that’s nice” and he goes on tour.

The Japanese, who’ve also seen the play, think that they should make their own. This is Gakutensoku, who is about 3 meters tall, is operated by pneumatic fans underneath, has a pen in his hand where he will write your fortune if the bird on his shoulder thinks he should. He goes on tour in Germany in the 1930s and is inexplicably lost. I do not know how you lose something that is nearly 3 meters high and pneumatically driven. He disappears.

The Americans have to make their own, naturally. This came from Westinghouse. His name is Elektro. He is about 2 meters tall. He has an extension cord that runs out behind him for power. He can dance. He can talk, which is extraordinary. He has a record player inside of him like a jukebox, and a voice command system. A very early one that if you triggered the right word, it triggers the right record that was played. He called everyone “Toots,” because it was the 1930s, I hasten to add. And best of all, he had bellows in his head so that he could smoke cigarettes, and blow up balloons, but really he just smoked cigarettes. He appears in the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. Everyone loves him. He’s in the movies. He makes his last appearance in the movies in 1952, I think, in a movie called Sex Kittens Go to College [1960], which is not what it sounds. It was nowhere near that interesting. He also disappears in about 1953. His head ends up in a frat house in California, being used to open beer bottles. The rest of his body is distributed into sheds and garages in Pennsylvania. He was reunited with all of his bits and bobs in about 2013, I believe.

So first you have a play, then you have a series of first engineers then companies attempting to make this thing come to life. And they’re struggling with all of the pieces. They’re struggling to make it talk, they’re struggling to make it walk, they’ve made it smoke cigarettes, which is weird. Hollywood on the other hand, not so concerned with any of those practicalities, and just charges forward and takes robots almost anywhere you can imagine.

First robot movie, arguably Metropolis, 1929, and after that it just goes. Lots of robots, lots of Hollywood movies, lots of tropes here. But usually the running thing here is that robots are not necessarily your friends. They are complicated, they are other, they are frequently dangerous. With the exception possibly of R2D2, who’s just surreal. Most of these robots don’t necessarily mean when. Sometimes they do, but for the most part they don’t.

So what’s going on in all of this? Where is the intersection of art and technology and what can it tell is about what technology might be. Because I think in making real, both in the movies and in the laboratory, you are struggling with four key challenges. I actually think these are challenges that are not just about robots. I think these are challenges about our life with technology. These are challenges about what it means to inhabit a world where part of our lives are digital.

Problem #1 is there is this problem of, in robots the body, or form. There is a man in Melbourne, I love him, who has a web site called Cyberneticzoo, and he has spent near as I can tell as long as there has been the Internet, and possibly previous to that, trying to collect and collate all the robots there have ever been. Like, all of them. He has an entire section on robotic elephants. (Many. Who knew?) Elephants are good, you can hide the motors; they make great robots. But he has a whole collection of humanoid robots dating back basically to the 1920s.

It’s probably about 150 of them, thereabouts. Two of them are female. One of them is marked as African-American. This one is clearly Japanese. The rest of them have no annotation. And what does that tell us? Every single other one doesn’t need to be marked with gender or race because they are male and white. So, a lot of robots. Most of the humans ones turn out to be boys, or blokes, or men. They’re certainly not women, and they’re mostly not ethnically other. Which is in and of itself immediately interesting. What is the imagination of the robot? In Rossum, some of the robots are female. But we’ve already turned it into a male thing.

The second problem of bodies is a more pragmatic problem, which is, what’s the thing going to do? Humanoid robots are actually really difficult. There’s a reason we’ve never made them really successfully. The walking piece, your knees and ankles as you get up to get out of here, you should just reflect on the fact that is really technically difficult. I can do it, robots not so much. Arms, pretty complicated, too. Hands, oh my god, really surprisingly difficult.

So lots of people have solved the robot problem by just making a piece. Think of mechanical arms in factories. Think of lifts. Lots of people have solved this by breaking the body into pieces because a whole integrated body is actually really difficult. But it also reflects, what is the thing you’re trying to get done? As designers, we routinely grapple with “what is the form?” What is the device? What is the glass? I’m still mesmerized by that yesterday; what is the size of the screen? What is the form you are trying to deal with, problem #1 for robots.

Problem #2, inexorably linked to problem #1 is What is is going to do? This is one of the only female automatons that exists. It’s Edison’s talking doll, 1915. She sings “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” in a manner that makes you think you should turn on all the lights in your house and lock all the doors immediately. She is the most singularly terrifying thing I have ever encountered, and I’ve seen a lot of stuff.

So the questions is what is the thing going to do? What is its purpose? What is its function? What is the thing this object needs to do? Does it need to be legible from a distance? Does it need to be scalable? What’s its purpose? Because that in some ways is hugely important to how you think about how you’re going to build it.

Next problem, very robot-specific but also increasingly our problem on the web because we think about algorithms, is how much autonomy is this thing going to have? My favorite sign, just outside of Tokyo. I got out of a moving vehicle to photograph this sign, because I’m an anthropologist. My colleagues stopped the car, got out, followed me and said, “What are you doing?”

I’m like, “What does this sign say?”

They said, “It’s a robot zone.”

I’m like, great. “Good. I can read that bit. What’s the bit I can’t read say?”

“Oh, it says it’s an autonomous robot zone and there are robots 2 meters in from the curb.”

“Who’s robots?”

“Autonomous robots.”

“What are they doing?”

“They’re 2 meters in from the curb.”

I’m like, “Aren’t you concerned about these robots?”

“No, that’s what’s the sign is for.”

“Where did the robots come from?”

“They’re autonomous.”

“How did they get here?”

“2 meters in from the curb.”

I’m like oh my God. And this conversation goes on the way ethnographic exchanges do when you’re getting it wrong because you’re not asking the right question. And I’m still going, “But aren’t you concerned about the robots?”

“No.”

I’m like, “But where did they come from?”

They’re like, “The sidewalk.”

“How did they get here?”

“We don’t care.”

And one of colleagues who knows me well finally said, “What is your problem?”

I’m like, “Well, aren’t you concerned that something’s going to happen?”

They’re like, “What?”

“… They’ll go mad and kill you.”

My colleagues looked at me and went, “Oh, that’s just American science fiction. In this country the robots are our friends.”

Because there is a completely different narrative about robots in this place. This is not a set of stories about robots and death, this is a set of stories about robots and friendship. This is not a place that needs Asimov’s Three Laws of the robot because there’s a very different history. But we know the question here about autonomy. How much independence are we going to grant an algorithm to decide what data we see? To decide what people we are paired with, what destinations we go, what images we throw out at the stream. How much autonomy are we going to grant the agents that act on our behalves in the digital realm, and what will the consequences of that be?

Robots are one of the places that question plays out, but almost every talk you’ve heard over the last two days is also about what the consequences are of algorithms for how we inhabit the world both physical and digital.

And of course if you’ve solved the problem of bodies, and the problem of purpose, and you have thought through the question of how much independence or autonomy you are going to grant, in this case the robot, but in any case a digital agent, you’re left with one last thing: What is it thinking? What will it inner life be?

Hollywood has taught us that robots have only two thoughts:

- Kill John Connor.

- “I have seen things you people wouldn’t believe. I have seen starships on fire off the belt of Orion.”

That’s it, right? We know what robots are thinking, it’s those two things.

Twitter has taught us, if you follow the self-aware Roomba as obsessively as I do, that Roombas worry about toast and crumbs and glitter. If you follow the Internet of Things Toilet (another excellent follow on Twitter) it tells you how much water goes through it on a daily basis. Turns out robots may be thinking about deeply mundane things. But we have this extraordinary unwillingness to imagine what it might be for these objects to have an inner life, ie. actually to havea life. Because in some ways the great fear, the fear of things coming to life, the fear that runs through Frankenstein and Golem and the Terminator sequence is a fear about what makes us human and whether it is distinctive or not.

If something else can come to life, can have purpose, can have form, can have autonomy, can have sentience, what makes us special? What makes us different? One of the anxieties frequently expressed about robots, but also about many digital objects, is if they have sentience and independence, surely the next they will do is kill us. The engineers in my laboratory frequently tell me this.

Masahiro Mori, a very famous Japanese roboticist, wrote this extraordinary book in the 1970s called “The Buddha in the Robot” where he speculates about what the inner life of a robot might be. He says every time we imagine that the robot is going to kills us, what we are in fact doing is projecting our own anxieties about mankind onto the machine we are building. Because of course the anxiety there is about what we have already done to ourselves. It’s not what the machines will do, it’s what we are capable of doing that we are really fearful of, and it’s easier to put that on the machine than it is to say to ourselves we are the people who brought the atomic bomb to the world. We are the people who brought pollution and climate change to the world. It is easier to imagine that the robots will kills us than to take responsibility for our acts here.

And he says rather wouldn’t it be extraordinary to imagine that the technology we built was the best of ourselves, not the worst of ourselves? What would it be to imagine a world in which a robot might achieve buddhahood before a person, because it is capable of infinite patience and infinite grace? What would it be if we imagined that technology was our best selves, not our worst selves. And what would it say about us if we could imagine that the technology would embody the things about us that were extraordinary: art, creativity, wonder, beauty, magic. What if that was what we were building? And what would it mean then to release that into the world?

So for me as I think about what it is that I’ve obsessed about robots for a year now, is I realize that it’s just another way into a conversation about what makes us human, and about what it is that we should think about the future. Because ultimately while we can talk about inhabiting a world that is made digital, the ones that will inhabit it are us and the things we make. So we can talk about the Internet, we can talk about technology, we can talk about things digital, but ultimately what we are really talking about is ourselves. For me there is something extraordinary to stop and imagine what it means to make a world that is as much about art and beauty and love and magic and wonder, as it is about technology, objects, bits, bytes, devices, and screens. And for me I want to imagine that there is a moment when we can look back on a thousand years of human history and a thousand years of human preoccupations and say, those are things we can all bring to the table. These are the stories that we inhabit, the stories that shape us.

But they’re also ones that give us incredible power to imagine other destinies. The world “robot” is a word of art. It is a word we made real through technology. It is a word that has continued to be shaped by art. And I want to imagine the same is true about everything else we talk about. About being digital, about being human, about being children of a technical age. I want to think that Frankenstein’s Monster, from the beginning of this talk is wrong. We are not the men of steam and mechanization, we are the people of a human world that we get to build however we want.