So, my name is Eirik Fatland. Or “Fat-land;” I know it’s fun in English. I have a Norwegian passport. I have a Master’s degree in new media. And I have a job in financial services. I’m thirty-seven years old, and for twenty of those thirty-seven years I’ve spent very large chunks of my time—my spare time and some of the time when I should have been working or studying—playing games of make-believe together with other adults. I am a larper.

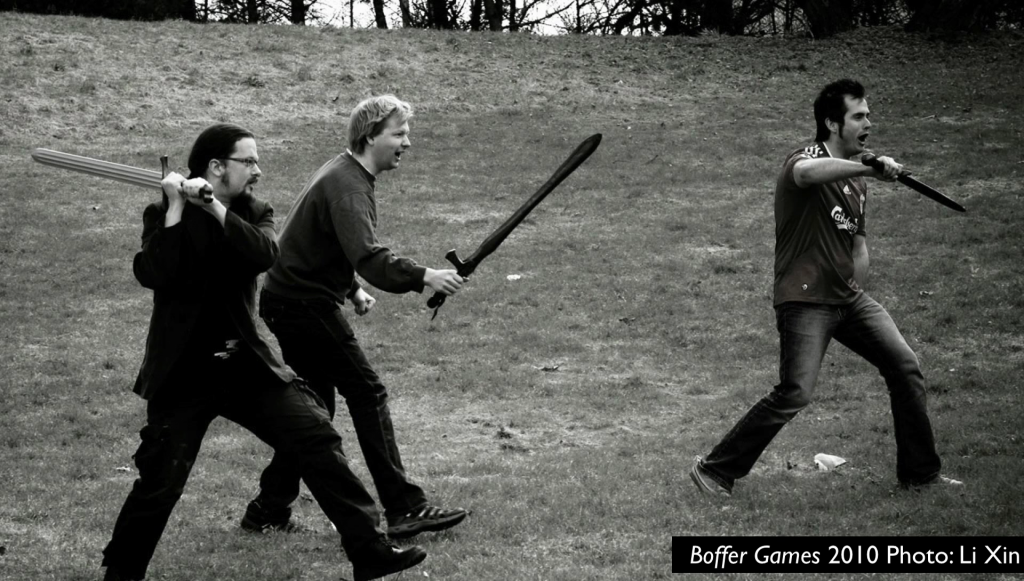

Yes, I have hit my friends repeatedly with rubber swords.

Photo: Xin Li

I’ve also performed strange rituals in dark forests.

Love in the Age of Debasement; photo: Xin Li

I have been dumped by women who were never my girlfriend.

I’ve also hooked up with guys, despite neither of us being gay. I have been a character in an Ibsen play and a character in a Monty Python comedy. I’ve lived for a week in the year 1942, another week in the year 14 AD. And altogether, I’ve participated in a few hundred larps, and I don’t know how many hours I’ve spent on this hobby.

Marcellos kjeller; photo: Xin Li

And as if playing larps does not take enough time, I have been and continue to be a larp designer. One that sets the stage for others to play. I’ve invited players to be grungy resistance fighters at a musical larp.

To be traumatized refugees at an asylum reception center.

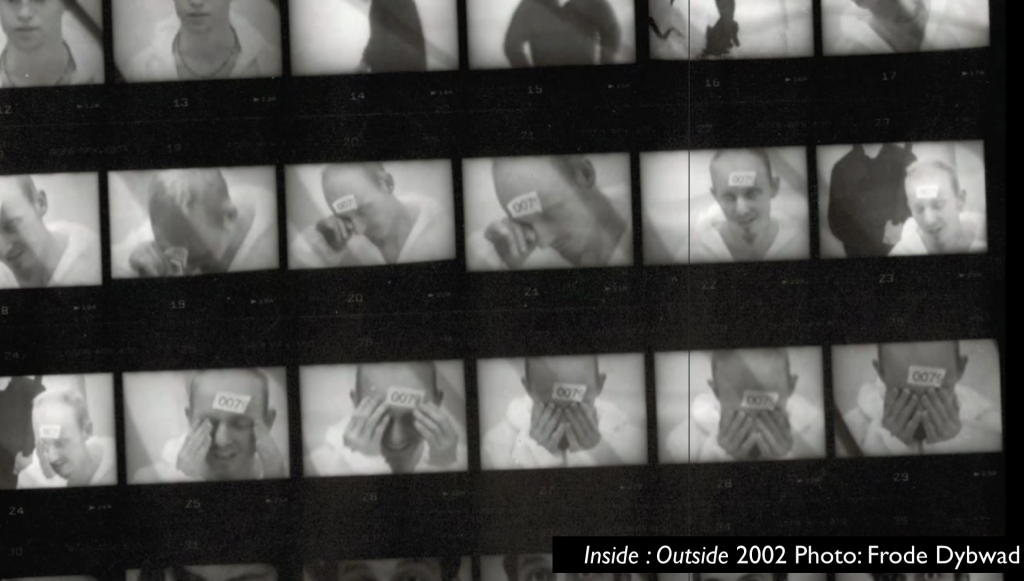

Ordinary people waking up as prisoners, forced to face impossible moral choices by a disembodied voice.

And at the tender age of twenty-one, I was the main guy responsible for locking one hundred and twenty young people up in a mental asylum. It was no longer a mental asylum. We used it to pretend that we lived in the year 1984 as depicted by George Orwell, for five days.

Now, society has on multiple occasions let me know that this isn’t really entirely acceptable. You should have seen the media attention after the 1984 game. But friends, relatives, coworkers, teachers and so on, keep implying, just hinting—sometimes being outright—that if I had done something else… If I’d worked harder towards being able to buy a BMW and a larger house, or to feed a growing family, or volunteer to help the poor and the destitute, or sell my talents as a writer or as an artist… Or maybe kick a ball around on a grassy field, that would all be good, acceptable, decent ways to spend your time. But that the passions I direct towards roleplaying, though they are tolerated (we live in a tolerant society), they’re also kind of weird and irrelevant.

So, while it has been getting better in recent years, I obviously have felt the need to ask the question myself: Does larp matter? And to tell you the truth, I’m kind of ambivalent. On sunny days, I see in live roleplaying the potential for transformation of the role-player into a more fully realized human being. And of art towards more democratic forms capable of depicting the human condition with a degree of intimacy and realism that is unthinkable in a spectator art. But on rainy days I think it might be just an incestuous, self-indulgent and [egregious?] waste of time.

But I’m convinced that larp design matters more than larping itself, and to more people than the people who design and play larps. And I’m here to talk about why I think that’s the case.

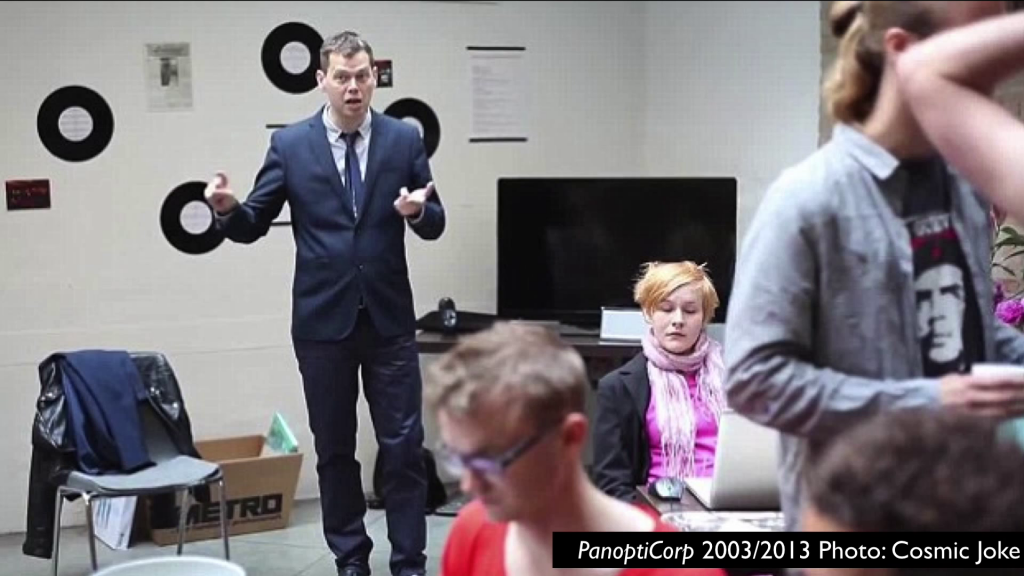

PanoptiCorp; image:

PanoptiCorp Mini Documentary 2013, Cosmic Joke UK

Now, let’s look at what larp designers do. This is a still from PanoptiCorp, a larp played twice, 2003 and 2013. It’s set in a fictive advertising agency. And the entire written material for this larp consists of a dictionary, thirty words and their explanations. And the words are the office jargon of this agency. They use terms like “NexSec,” which kinda means cool, but if it a cool that’s not NexSec, that’s “mundy,” and mundy’s bad. They used words like “HotNot,” which is a vote that is held daily to determine your “CorpCred,” which in turn determines whether you have a job or not.

Now, by adopting those thirty words, players learn enough of the mindset and the ways of working and office routines and so on of PanoptiCorp that they’re able to simulate a dark, cynical advertising agency with some humor and an alarming degree of immersion.

The Danish larp Totem, 2007, used a series of drama techniques, several workshops in advance, that turned a group of young Scandinavians into two rigidly hierarchical and highly complex tribal societies. For example, they reportedly (I was not there) used the rule that it is inconceivable to talk about someone who isn’t here with us right now. And based upon a set of these simple rules and workshop and body language and so on, these highly complex and subtle societies emerged.

AmerikA. Well, this is AmerikA in Oslo, Norway, the year 2000. Works also with a group of ordinary young Norwegians; no actors, no special talent. Worked with them over three weekends to define their characters, through drama exercises and so on, and then placed them in the midst of this huge pile of garbage. Which was actually very cleverly scenographed. You could walk around there, hide inside there, and so on. There were plenty of things to discover. And by doing so, they were able to bring not just to life a society of the thirty, forty, people who had been through those workshops. Those thirty, forty people are able to drag in one hundred more people into this society, living in this area. And as you can see, this picture is taken from above. There were thousands of people who watched this in real time; stood there glued, looking down on the world out there.

Now, we larp designers, we do our thing by inviting players to act as if. As if they’re knights. As if there is a dragon. Or as if they are a group of immigrants celebrating Easter. There are many kinds of larp. And larp of course is not unique in asking us to present as if. Children do it all the time. Adults do it, too. If I tell you a story where somebody says…like, the story ends with somebody saying, “Fuck off!” Then, you don’t actually act as if I just told you to fuck off, do you. Because you know that I’m acting as if I was a guy saying “fuck off.” And you are acting as if I didn’t.

Now, this is not just a matter of games and stories, of metaphor. As Markus Montola explores in his PhD thesis, which everyone should read even though it’s very difficult, a great deal of human society is built in different ways on what I would say is people acting “as if.” As if the bread that you consume is the body of Christ. As if the policeman who just arrested you is an embodiment of the state and not just a person like you. As if a sound, “stone,” is related to an object, physical stone. And as if this here piece of paper [holds up a bill of paper money] is the equivalent of a cow.

Now, when we design larps, we’re playing basically with the building blocks of culture. Not just of fictional cultures, real culture as well. But asking people to act as if is not enough to make a larp. As larp writers, we need you to act as if, together. Because if I act as if I am a merchant from the fictional city of Libidibi and I meet you, and I greet you like this, [bows while holding nose and holding other arm across chest] then you have no idea whether what I did was actually a symbolic compliment to your eye color or a great insult towards the grave of your mother.

So, to enable roleplaying I need to identify the rules and the symbols that actually matter. And I need to reduce these to their minimum components, their minimum requirements. Not a whole language, but the thirty words that matter. Not a whole society, but the body language and the rituals that create a behavior that is most different from our own. And then I need to communicate those requirements, so it’s not just the one guy from Libidibi who knows what this means, but also some other people who can interpret it, and then there is drama, there is action, there is society, and we have larp.

And I cannot micromanage the players. That’s a big advantage of being a larp designer as opposed to a theater director, a writer, whatever. They’re going to do their own thing no matter what. I need to ensure that the tools that I give to players (the body language, the characters, the ideas, the language, and so on), that they work together. They fit together. And then they allow those players to improvise something that also fits together and becomes increasingly beautiful, or increasingly funny, or increasingly profound.

So the bottom line is this. That what we do as larp designers is to describe and communicate the minimum requirements needed to direct human creativity towards a shared purpose. And directing human creativity towards a shared purpose is not a small thing. It is the primary challenge of any project, any community of small businesses and of corporations, families and clans, dynasties, cities, nation states, and civilizations. The resolutions to all of the big questions of our time, whether it’s getting rid of dog poo on the sidewalk, or solving the climate change crisis, all of these are basically problems of directing human creativity towards a shared purpose.

While that’s not a small thing, it is a very very challenging thing. Now, let me first tell you about something that isn’t very challenging. And that’s to direct humans towards a shared purpose. Not creativity but just human beings, their bodies, and their ability to control those bodies.

Pink Floyd, The Wall

We know very well how to do this. We threaten them. We punish them. We hit them. We tell them what will happen. We fill them with a bit fear. We might tell them grand lies for them to believe in and so on. But eventually they internalize that fear. They replace your voice with a voice inside their head, telling them to go here read this do that.

But directing human creativity is much harder. Because creativity describes our ability to generate and execute ideas. Creativity is complex problem-solving. And creativity does not thrive on fear. All authorities on creativity agree on this, that it requires fearlessness. It thrives on playfulness. And creativity also does not thrive on solitude, despite the myth of the sole genius. Neither Einstein nor Picasso would have been worth very much if they did not have a common language with other physicists, other artists; if there were no people who challenged them, listened to them, continued their work.

And so this is where we find larp and larp design. Now, obviously we’re not alone in working with issues of directing creativity towards a shared purpose. There are many others. There are art directors, theatre instructors, service designers, game designers, process planners, information architects, politicians, activists, teachers, urban planners, managers of so many different kinds of stripes. Project managers, mid-level managers, etc., etc. Scrum masters, six sigma black belts, and so on.

And then there are also plenty of people who are researching this. Social psychologists, game designers scholars, and so on and so on. There are lots of people who are worried about directing human creativity towards shared purposes, not just us.

So, what makes us special? Why are we unique? I think we have two basic advantages over all these other fields. The first advantage is that we prototype, and we prototype rapidly. Now, in the Nordic larp tradition, we have simulated the institutional structures of slave-owning societies, advertising companies, IT companies, real and fictitious militaries. We have lived in societies with four genders and no genders. We have recreated daily life in the years 1349, and 1942, 10,000 BC. We have experienced the inner dynamics of hundreds of societies, thousands of families.

Larp might be based in games of make-believe, but by enacting those beliefs with our whole bodies, we make temporary realities. And nobody else does this. There’s no other branch of knowledge or practice that can build a religion, test it out for five days. How it feels to be a believer, how belief affects action… And then use that experience to build another religion next year. I mean, the idea is inconceivable, right? But we do this all the time. The speed by which we can put imaginary social and creative constructs to the test enables us to learn much more quickly than any other discipline.

And secondly, we are multidisciplinary. I’m speaking here on the evening before the beginning of the seventeenth Knutepunkt conference, which since 1997 has been keeping conversation going on larp design, larping, larp theory, and so on. And where we’ve been basically using whatever we can come upon, experimental larps and various branches of knowledge, in order to improve the practice of larp design. And you know what? All of these professions are in this room now.

We may be multidisciplinary as a result of our passions for larp. When we need to make a living, we are drawn to adjoining fields, but the kinds of professions that actually pay you in real pieces of paper. But we are also multidisciplinary because we have to be, because larp can depict the totality of human life, and so must draw on the totality of human knowledge.

Does larp design matter? The toolbox of larp design contains ideas and symbols and rules and practices. These tools in turn allow us to build groups and companies and cultures and institutions. The tools come from any and all branches of art and science. The tools keep getting tested and refined. Some tools we have thrown away. Many others we have made sharper. And we still discover new tools. And so the toolbox keeps evolving, and we’re getting better at understanding those tools, and are teaching those tools to others.

We’re not really there yet, to be honest. It’s only two years ago that we started figuring out how to teach larp design, and then started realizing how much we still needed to figure out. Because you need to know a thing to teach it, right? But I think we’re getting there. And as our toolbox evolves, I believe we will find, and that we are already finding, that we can put the same tools to use to design real symbols, rules, roles, and practices. And hence new kinds of culture, organizations, and movements.

As such, larp design represents a new kind of leadership. Not the leadership of hierarchy or intimidation. Not the kind of leadership that’s easily transplanted into our schools and companies. But the leadership that works by inspiration and by invitation. Building better playgrounds rather than pushing kids around. A kind of leadership that will found institutions, instigate movements, and that may come to empower us with the rules and roles and symbols we can use to bring forth the best in ourselves, and to work towards realizing our highest aspirations. And this, I think, is why larp design matters. Thank you.

Further Reference

Overview blog post for the 2014 Nordic Larp Talks, and for this presentation