[Photos throughout are by either David Ewald or Marcelino J. Alvarez, as noted, unless otherwise indicated.]

James Keller: Hey there everybody. How are you? So, here we are. My name is James Keller, and Marce and I work for a little product design studio in Portland, Oregon called Uncorked Studios. And at Uncorked, we look to find the connections between people, technology, and context to create change. We do that for folks like Google, Adidas, Samsung, Intel. We make everything from wearables, to interactive full-wall installations, to web sites. But more than anything we like to build products with purpose.

My role there is as—and I apologize, my title is a mouthful. I’m the Executive Director of Semiotics, semiotics being the study of meaning. So I aim to put the work that we do in context. But, I was an interaction designer for about two decades, so I am amongst my people. So I’m very excited to be here. And this is Marce.

Marcelino J. Alvarez: Hello. So, I’m Marcelino Alvarez, and I am Founder and CEO of Uncorked Studios. I come from a production background, actually. I was a producer in advertising for a number of years before starting Uncorked, and ironically enough, this is my second time in Lyon, my first time having been for a project that really inspired kind of the foundation of Uncorked Studios. It was 2009 and we were here with Nike and the Live Strong Foundation and we built a mechanical street printer that you could send messages of hope and inspiration to. It was for Live Strong Foundation—obviously we all know how Lance’s chapter ended. But, it was a project that brought me close to the intersection between physical products, software, and hardware technology, and a large global stage to create change.

Keller: Alrighty. So, I want to talk a little bit about the ties that bind us. And when I originally set out on this, I was thinking I just wanted to explain how Marce and I are alike? Because at the end of the day we’re even teased around the office about being optimists. And who knew that that could be such an insult, but sometimes it is. But at the end of the day, I actually believe that my optimism is a superpower. And at the risk of sounding like a beauty queen, I believe that I can make the world a better place.

And this is where I believe this is the ties that bind all of us together. Because I believe fundamentally that design is an act of optimism. We believe that by trusting the process, and through our own blood, sweat, tears, effort, and anxieties, we can solve a problem in the world and make things a little bit better. Which is a really amazing thing to be able to do, to be a part of this community that are out there creating change.

But before I talk about how a couple of crazy designers and technologists in Portland, Oregon were flown around the world on diplomatic missions, we need to start with an apology.

Alvarez: So, like James said, I think there’s a backdrop that we need to acknowledge before we talk about the role of American diplomacy. And that is that we need to acknowledge the elephant in the room. And in our case it’s an orange elephant that has made the conversation around diplomacy pretty complicated. As we know, the conversations over the last fourteen months, the discourse in American politics have made it very difficult for American diplomacy to really stand out, whether you are an official member of government or a private non-state actor hoping to impact change.

And I believe that there’s two ways of looking at this. I think the first is a really deeply skeptical view, one that posits that American hegemony after the Cold War has been in constant decline. And this is a view that’s supported by two Gulf Wars, a war in Afghanistan, failed policy initiatives in Syria, in Myanmar, and the possibility of nuclear war in North Korea. It is a view that suggests that any non-state actor trying to encourage flip diplomacy, people-to-people connections, faces a serious credibility challenge. And this is a really deeply skeptical view of the world, which may or may not be true.

However, the optimist take on this is a little bit different. And that is that this new sense of urgency that has been created in the private sector, because of and in spite of an administration. And this view is supported by a number of factors. The Women’s March in DC. The Science March. The Me Too movement. The 25,000 women who have decided to run for public office in the United States using Emily’s List. These are all organizations and missions that are being driven forward in spite of the incompetence, the malevolence, the misogyny, the racism, and the possible collusion of the current administration.

And it is with this optimist view, through this lens, that we as designers have an ability to provide perspective, to bring focus, and to share the tools that we use on a daily basis to align a group of disparate voices for a cause that is greater than our own. And like James said, I’m an optimist so I prefer that take.

Keller: So, we’ve got our talk today, a story in three acts. So we’ve got definitions, because you know, as designers if you ask someone what design is you’re always going to get a different take, so I always feel it’s good to sort of anchor on these things. Then we’re going to tell you a little bit about the work that we’ve been doing in diplomatic channels. And then hopefully we’re going to frame for you a call to action so that you can understand how you too can participate in bringing change to the world. And as I mentioned I’m head of semiotics, which is around meaning. So definitions are near and dear to my heart. Before I went into design I was very much a word nerd, so I love this stuff.

Design is a plan for arranging elements in such a way as best to accomplish a particular purpose.

Charles Eames [presentation slide]

So yesterday I know that there was a talk about an interactive game at the Eames offices. And I think everyone here loves Charles Eames because of the great work that he did. But this has always been my favorite definition of design. Because I feel like it’s boiled down to its most simple parts. I love the fact that he talks about arranging elements. And elements can be anything. They can be boxes and arrows. They can be marbles in a tray, right. But we do something with intent to accomplish a purpose. And again, that purpose, that goal is the thing that makes design have impact. So I love this definition.

Successful diplomacy is an alignment of objectives and means.

Denis Ross [presentation slide]

Now, as I was looking to anchor on a definition of design that was going to help us set the framework for this talk, I also wanted to look at what diplomacy means. And so I came across this quote by a man named Dennis Ross. And Dennis Ross is notable because he’s actually a very well-known American diplomat in modern society. He served under George Herbert Bush—the first. He worked under Bill Clinton and the Secretary of State. And then he also was an advisor on the Middle East to Hillary Clinton. And the way he talks about diplomacy is that successful diplomacy is an alignment of objectives and means.

So the interesting thing when you take these two definitions and you sort of pull them together, you have objectives and purpose, means and elements, alignment and plan. And boiled all the way down, design equals diplomacy. And this is something that we had found, as we were doing our work, it was really interesting to see that come to life in a much different way.

And that just sort of grew. We realized that there were a lot of parallels that were hard to ignore. And one of those themes is around intent. You hear the word “intent” a lot with design. It’s something we throw around the studio a lot. And I love this photo. It’s from a statue in Havana of a man named José Martí. And José Martí is a celebrated hero in Cuba. He was a radical individual for Cuban independence. But he was also known (and you see him holding a child), he was also known as sort of the grandfather of Cuba because he wanted to bring education to the masses, and Cuba to this day has one of the best literacy rates there is.

But the reason I love the statue is that he’s pointing, with intent. José shows the world that he has an intention in what he wanted to do. And I feel that this is something that as designers, might not feel quite as statuesque, but we go at things with a very clear objective.

Another theme that we saw between diplomacy and design is that you have to trust the process. And this actually, I was thinking about this the other day. This goes really deep as a designer. Because we trust the process so much, we charge other people and they don’t know what they’re going to get. We say, “No, really. Come along this journey. We’ll have some objectives on the outset but we don’t know what you’re going to get at the end. Come with us.” And so we believe in that. And that’s why I fall back on this thing of optimism. We trust the process enough that if we bring the right tools, the right people, and the right energy to anything, that we are going to build something from nothing.

And diplomacy is very much the same way. When two countries are sitting around a diplomatic table, they both have their own objectives but at the end of the day they try to align to bring those objectives to life. And it requires a little bit of a tango. Very similar to design, if you’ve ever had a conflict with a client or an internal partner you’ll understand that. But at the end of the day you work towards a greater solution.

Fringe Diplomacy explores the space just beyond the boundaries of states and governments’ capacity and authority in international relations by focusing on smart, strategic and meaningful human interaction and engagement.

[presentation slide]

And so it was with that that brings you to the interesting part, where we through a bizarre kind of seemingly unconnected people, places, and times, we got connected with a group out of the Aspen Institute in Colorado called Fringe Diplomacy. And this is the definition of fringe diplomacy. And really what it aims to do is in places where diplomacy is not tenable for whatever reason, or is challenged because of the nature of what’s going on politically, Fringe Diplomacy wants to create deep connections between people. So where the sometimes the governments may fail us we still have solid foundations across the world. And in this, we were able to go on several diplomatic missions as a part of Fringe Diplomacy to wield our skills in a new and interesting way.

Alvarez: So in 2015, with kind of a backdrop of a rapprochement between the United States and Cuba, we first joined a partnership opportunity delegation that connected in emergent class of Cuban entrepreneurs with their counterparts from the US. And it was amazing for a number reasons. I think one was kind of this newfound optimism. But I think that it also had the complications of the history of fifty-five years of a failed foreign policy between the two nations. And so we wanted to create a little bit more than just kind of a meet and greet. We wanted something to be a little bit more interactive, a little bit more hands-on, and something that could provide more value for both sides.

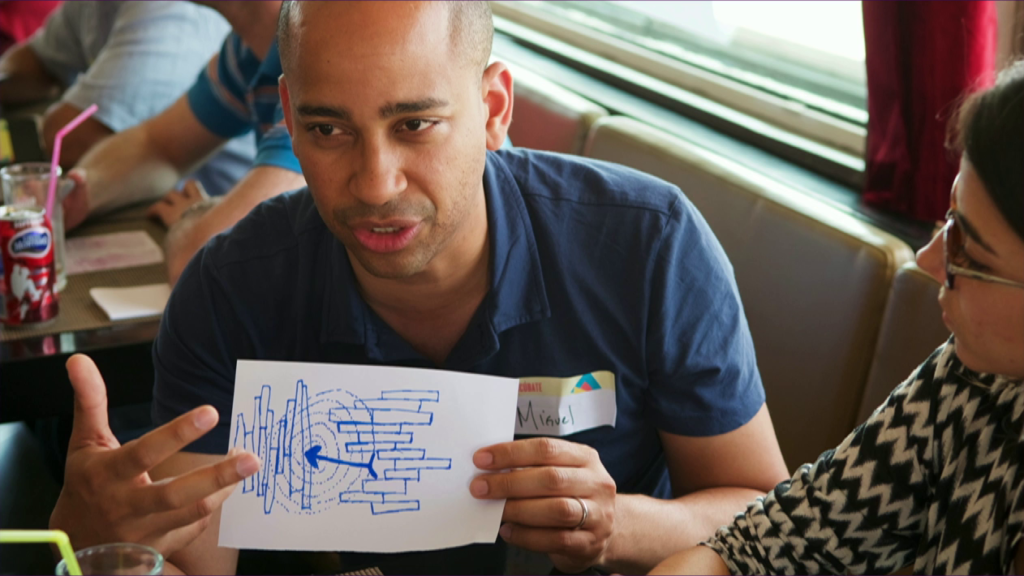

And it was with that that we created Incúbate, which was a two-day design thinking-modeled workshop between Cuban entrepreneurs and their counterparts in the United States. We wanted to acknowledge both the complexity of the history, but again, find that optimism as kind of a guiding principle for us.

And admittedly, when designing a program like this, I think we wanted to be careful that it wasn’t perceived as a bunch of Americans showing up with tablets on high and saying, “This is a design process,” or, “This is how we build startups in the US.” We wanted to make sure that our process was rooted in both an understanding of the values and the systems and the challenges that we each face as either entrepreneurs, as technologists, as restaurateurs. But also kind of having the same kind of dialogue that you might see in kind of a healthy startup ecosystem, like, “Hey, did you see this tool? What do you think about this? Let’s share. Let’s remix and adapt.” And so we needed to find common ground. We needed to share openly. And admittedly we had no idea what to expect.

So over the course of two days, I would say that the American entrepreneurs learned as much from their Cuban counterparts as vice versa. I think the Cuban entrepreneurs were designing within constraints and innovating in ways that I think made it really impressive and kind of reminded us how much stuff we take for granted on a daily basis.

And admittedly I think the Cuban entrepreneurs were also open and eager to sharing about things and kind of iterating. So one of the the moments that was kind of a highlight as we were talking about org charts—which is never something to get excited about. But we’re trying to map out like a sales versus a marketing system with a startup that was building a Yelp-like product in Cuba. And so he had this aha moment where he understood kind of the difference between the two, and he was sharing with a CEO from New York. And they both had the equal aha moment about like, “Oh. This is new to you, this is new to me, and how do we share this?”

And I think it’s worth noting too that the entrepreneurs that we were working with weren’t just technology entrepreneurs. That we had folks who were starting restaurants or building sustainability products. And admittedly they were designing solutions for problems that they saw in their own community. And a lot of these problems were things that from an outsider’s perspective might not be glamorous. It might not be something that you would want to start a business around. It might not be something that an investor in Silicon Valley would say, “Hey, I’ll write a million-dollar check,” for. And that’s fine.

And that’s fine for a number of reasons. We have a friend in Portland, Mara Zepeda, who wrote a blog post called “build zebras not unicorns.” And she’s one of the founders of the Zebras Unite movement. And she says you know, unicorns are mythical creatures; why are we trying to chase after these unicorns? But zebras are real. And zebras are black and white. You can have a balance between the two. And in the case of startups you can put both profitability and purpose on an equal level. She also suggests that zebras are kind of a flocking, kind of herding animal, and that individual contributions by one benefit the entire ecosystem.

And so you know, in this conversation you look at the balance of startups that maybe are perhaps zebras and not unicorns, that they have this sense of community. They find commonality in their shared purpose. But they’re also limited by the the ecosystem that they’re within.

And so we were able in our conversations with the Cuban entrepreneurs to really look at the startups themselves and kind of share in that discourse. The ecosystem I think is something that fell outside of our purview.

And I would say that over the course of the next three years (we started in 2015), we learned quite a bit. I think one was kind of the changing tone of the dialogue and the discourse, depending on what was happening outside of kind of our purview. Certainly the national discourse; the orange elephant in the room, as it were.

And I think from the Cuban entrepreneur’s perspective, in a number of ways they leapfrogged the tools that we were originally kind of using in the first couple of workshops. And so it became less about understanding an effort/impact matrix, or how you might prioritize things, and more about how do we shape policy so that it supports the needs of Cuban entrepreneurs? How do we maintain continuity between workshops that are held twice a year?

And so we explored a number of things from what would a shared coworking space look like, to what might an incubator in Havana look like. And again, in those situations we kind of ran against some kind of external hurdles. And then the orange elephant happened, and there’s kind of been a little bit you know…cooling of relations between the two countries. But we still remain in contact with the entrepreneurs and are hoping to kind of find our pathway forward as things hopefully warm again.

Another area where we joined the partnership opportunity delegation was in Beirut in Lebanon. Our chief design officer David Ewald went for a one-week-long session focused on startups in the region, led a two-day UX workshop with a number of those startups. And those also were from a variety of industries, from the nonprofit industry, to technology, to fashion as well.

And I’ll make a quick shout-out actually to David. He’s also in addition to being a designer an amazing photographer. And so any photo you see in this deck that’s well-composed, he took. And anything that’s blurry is something that I’m responsible for.

So, over the course of a week, he met with a number of organizations. So UNICEF in particular had partnered with a three-person startup in Lebanon, and they were looking to develop an application for refugees in one of the camps. And they had basically a rudimentary InVision prototype and needed to scale from that to about a million users in the course of a year or so. And so a part of his workshop aimed to provide focus and understanding of what an MVP product might look like that balances both the needs of the ultimate users as well as kind of the the need for scale.

There were also a number of entrepreneurs focused on fashion and kind of designing products that reflected their worldview, their perspectives, or their kind of creative goals. And again, I think in the discourse kind of finding common grounds, where we align, and then again, sharing the tools that we use to prioritize and inform product directions.

And then one of the interesting places where kind of our diplomatic conversations took us towards was this conference in New York called the Concordance Summit, which is held in NYC during the UN General Assembly week. And so you have heads of state and leaders from a number of large organizations meeting with private organizations kind of under the guise of public/private partnerships.

And so we originally were asked to lead a conversation around some of our efforts in Cuba, which we took to mean let’s talk about some of the insights, much like we’re sharing here today. And it wasn’t till I sat down at this table and kind of looked around that I realized there are four former presidents sitting at that same table from various Latin American countries and Spain, and the Organization of American States.

And then the introduction, you know, we had written some kind of prepared remarks around workshops and design thinking. And at the beginning they looked around the room like, “Great, we’re gonna lead this entire conversation in Spanish,” which is my first language but certainly not one that I lead diplomatic conversations quite often in. And while I was feeling quite a bit of impostor syndrome sitting on that stage, found my voice in kind of sharing the perspectives that people interacting together, people-to-people diplomacy, can move much faster than government-to-government diplomacy in spite of some of the challenges that we face at a national level.

The conversation did get a little heated, and I think I found myself representing both the opinion of the US and Cuba as the same person, as I was the only person representing both. And so I think that may or may not have been a diplomatic first. But we found ourselves there.

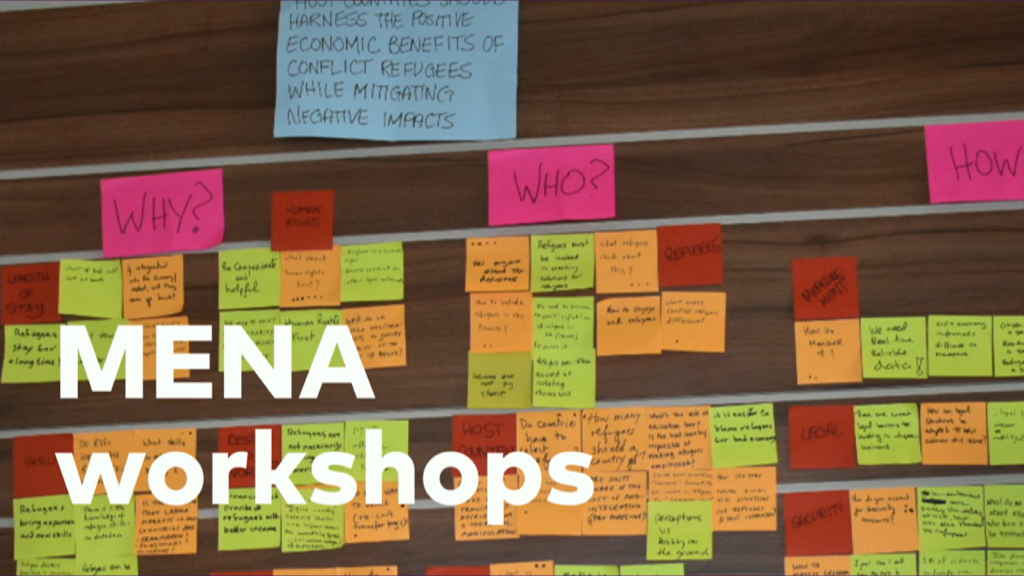

Keller: Because of the work that we had done in Cuba, I also had the opportunity to conduct a couple of workshops at a privately-held conference for people in the Middle East and North Africa. Attendees included everything from diplomats, to career politicians, academics, entrepreneurs, and even royalty from all over the region. So there were Israelis and Palestinians and Libyans and all flavors and shapes and sizes of people in the room with me. Again, I understand that notion of impostor syndrome.

The reason that I was able to be invited to this special meeting is they had traditionally had—actually very similar to that last slide—a bunch of people sitting around the table with placards. And our contact who runs Fringe Diplomacy realized that that model of communication has its limits. And so he really wanted to do some sort of interactive session in order to get these different minds together working collaboratively in solution space. So we ran one workshop that with on how do we empower, and what are the challenges for women entrepreneurs in the Middle East and North Africa. And then the second workshop, and this is where I felt very much out of my depth, was around understanding the economic opportunity and impact of conflict refugees in host countries.

But this is where I got to trust the process. I’ve facilitated all sorts of things in all sorts of places, and ultimately this was no different. If people are willing to come to the table and communicate, even if they disagree that disagreement actually provides a very deep well of insight that can breed empathy and get you to broader solutions. So that was a really incredible experience where I got to use my design skills.

Alvarez: So, one of the things that we would do at each of the the workshops was the kind of do a quick retrospective. So what would you want more of? What do you want less of? What did we learn? And that was kind of a quick way to grab a snapshot right then and there of what people’s perceptions were. And this sticky in particular I think always resonates with me. A, because of the person who wrote it, this woman Gretel who was basically kind of like our tour guide/fixer in Havana. And she had been through a number of the workshops with us, but she’s also been through a number of tour groups of folks from all around the world coming into Cuba for various reasons. And so I think she had both perspective, where she could have been a skeptic and a pessimist and said you know, folks are coming in and they’re trying to influence the future of my place.

Or you know, the optimist perspective, which I think is this: it’s that we’re all very much alike, despite the differences on the surface and differences in policy. And I think when you break down some of those governmental and bigger kind of policy barriers, you get to the fact that we have more things in common than we do that are different.

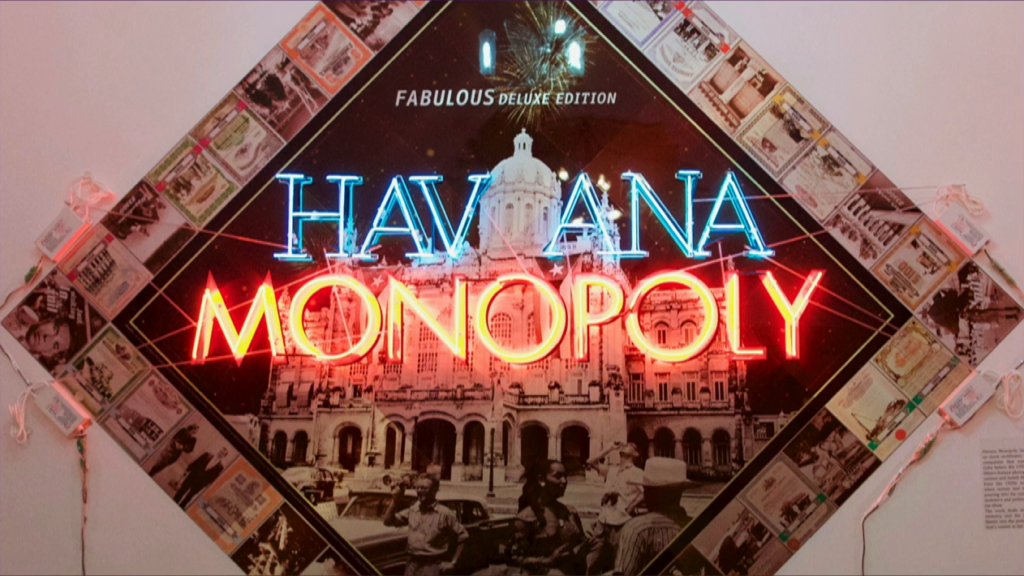

And so I want to talk a little bit about some of the insights that we learned, both in the the pod experiences as well as kind of the broader diplomatic ones. And I think one is kind of the role that art and design have in terms of influencing you know…as kinda being the art of communities and kind of the focal point for both conflict and kind of expression of angst.

And so this in particular is one of my favorite pieces of art that we saw in Havana. It’s by an artist named Kadir López that restores old neon signs. So he’s got basically an awesome task of restoring all the old neon signs in Havana but then kind of using it as an expression of kind of protest art. So you can imagine kind of Monopoly and pre Fidel-era Cuba, and kind of what what became of the old kind of Atlantic city vibe of Cuba.

But if you look at art as kind of a voice of kind of the resistance, this is something that is common not just in Cuba but I think universally. That it becomes a tool to express both out discontent, our perspectives in the world, and the tools that we have before us.

I think secondly is the idea that economics and industry are tools of momentum. So, startups in Cuba are conducting where the literal physical infrastructure has failed. In many ways, they’re poised to leapfrog things that we have faced in our country in terms of things like mobile payment or potentially blockchain technology, because they don’t come from like a web-first or computer-first model. It’s similar how in Kenya mobile payments kind of leapfrogged the US as well.

But I think you know, against that optimism I think there’s also politics that provide constraints which are also forcing functions for creativity. So as James said, all Cubans are designers, and I think one of the things that you see are that constraints are sort of a source of innovation. And if you look at the types of things that VC’s fund, it’s people and hustle and those behaviors that we look at in terms of investing capital and resources in individuals I think are part of the system. And I think it’s part of what Ross Baird calls single-pocket thinking.

So Ross Baird is the CEO of Village Capital. It’s a VC firm based out of DC that is focused on investing in startups that aren’t typically the startups that you might invest in. And one of his anecdotes that he gives is the story of the first time he went to ask someone for money to raise a fund for what basically are zebra companies, companies that balance both profits and purpose.

And so he goes to a potential limited partner, somebody’s he’s known, and says, “Look, I’m raising this fund. Here’s what I hope to do with it. Here the type of companies that I hope to invest. Here’s our thesis.”

And the LP says to him you know, “Ross, I’ve got two pockets. And in my left pocket I have all the money that I’ve made in the world that I use to basically invest in other startups. And in my right pocket I have my philanthropic pocket. Which pocket are you asking for money from?”

And Ross said it doesn’t have to be left or right pocket thinking. It can be soul pocket thinking, where you can balance both profits and purpose together.

We knew going into Cuba that we weren’t going to solve the challenges that both Cubans and Americans faced overnight. And admittedly, I don’t think… Initially looking back, I don’t think we realized that we were the ones that were probably going to be taking a step backwards, given kind of the orange elephant that entered the room. And so the question became how could we as designers use the tools that we share both for diplomatic purposes, with colleagues, with potential clients, as a better way or mechanism to understand our own identity, our own areas of focus, and how we define success?

Keller: So this is the part, now that you’ve heard a little bit about the amazing work that we have been lucky enough to do, where I make a plea to you all to make this your story as well. As Marce mentioned in the beginning, the time is sort of now to act. I don’t know how all of you feel, but I get really tired of the news cycle these days and I find a lot that’s happening in the world to be overwhelming. And that’s not the time to pull back and hide, it’s actually the time to take the skills that we’ve all cultivated through doing the work that we do and actually use that. And trust our process. So I’m going to take you through a few of those skills, sort of soup to nuts. But it’s all things that we as designers use in our everyday work.

So, the first thing is understanding the problem and really being able to dig in to understand all of the nuance that happens around a certain thing. Because problem definition allows us—just like we started with those definitions, problem definition allows us to really gain a shared understanding of what we’re working against, and that is very very very important.

Next is context. So, at Uncorked, the way we talk about context is defining the why. Why should the thing exist? Why is someone paying us to make a thing? Why would someone care? Who— And as advocates for the user you all are very familiar with “who” in doing good ethnographic research. And then we also have on the other hand, we have the how. So, in our company we build everything from wearables to walls. So the how is not always a clear path. And so making sure that everyone has a shared understanding of those three components is a huge part of what we do. And it’s no different in diplomacy when you’re trying to solve a world problem than it is when you’re trying to figure out what to do with a wall.

Next, empathy. A great colleague of mine, Jeannie, used to bemoan the fact that we are professional empaths. Which means sometimes it’s really hard to turn off the noise in our brains because we’re so good at seeing through the eyes of other people. And in diplomacy I think this is equally as important. And the reason I actually chose this photo is this gentlemen is amazing. He is a government-paid (because everyone in Cuba is paid by the government) lounge singer in Varadero resorts on the coast. And so he comes and sings Frank Sinatra covers to a karaoke machine every single night. He’s so old that he can’t stand while he sings anymore. But he does have an amazing voice.

And the thing that was interesting is when we were in workshops with the more traditional entrepreneurs I felt very much amongst my people. But when we went and met this gentlemen I was shocked to realize how different his world is. He gets paid the exact same, by the way, as doctors, schoolbus drivers, teachers, lawyers. No matter what they all make the same. But his life is singing for tourists.

So when I’m thinking about solving problems for Cuba I always try to remember that yes, I feel the needs of the entrepreneurs very easily, but are the actions that I’m taking creating a context for this gentlemen to live his life happily as well, and that of his kids and his grandkids?

Contingency planning. So we talked a lot about optimism, right? And the thing about optimism as designers is it’s something that we very much have. But pessimism also allows us to be great contingency planners. So understanding the different potential paths that you go through. And that’s something that we all do in our day-to-day.

And then lastly is facilitation. This is actually the skill that got us, I think, connected with this community of diplomats and have allowed us to do that work in a meaningful way. So, you have the skills at your behest. It’s something all of you do professionally. So, then what?

Alvarez: So, people often ask us why we engage on these adventures? Which is typically followed by, “How is it that you guys make money?” Or, “Do you guys make money?” And you know, I think it’s a good point to note that good does not always equal profit, and that’s okay. I think in the case of both the Zebra movement and the single-pocket thinking, you can balance out purpose and profit without compromising the two.

And honestly, I think that our efforts with Fringe Diplomacy kind of reflect both single-pocket and zebra mentality of how we approach the world. And I think it’s really similar to the open source hardware movement, where you’re not looking to necessarily make money from the initial effort, but you’re looking to build expertise. And organizations and people who are looking for that expertise ultimately make their way, through a convoluted mess of connections, to say, “Hey, we heard you were doing this thing. Could you help us with this other thing?”

And in our case that’s led to any number of opportunities. This was a hardware workshop we did this weekend with an organization called ChickTech, where were reconnected our colleagues to basically a community of the next generation of female entrepreneurs, hardware hackers, and technology leaders.

It’s also led to projects with large organizations. After the hurricanes in Puerto Rico I texted a friend of mine who worked at Carnival, and fast forward to a workshop, then to a meeting in Boise and we were meeting with leaders from Puerto Rico housing, banking, and finance to understand what infrastructure might look like. And so you never know where it’s going to lead and I think that’s okay.

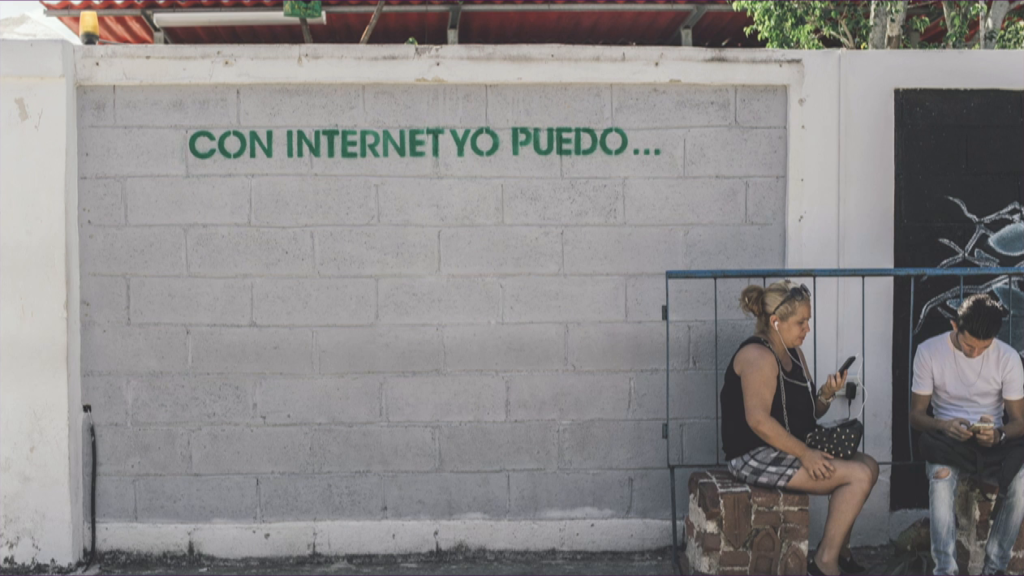

And I think ultimately it’s about community. And this is probably one of my other favorite photos of from Cuba. This is outside the collaboration between Google and an artist named Kcho. They have an Internet facility, and for those who don’t read Spanish it says “with the Internet I can…” And I believe that with community we can. And as designers we must. We are in a world right now where we cannot rely on public/private partnerships the way that they used to be run as philanthropic endeavors. We cannot rely on governments in the case of the folks across the Atlantic to provide the solutions. And we must look towards tools that we have to design the future that we want to live in. Thank you.

Further Reference

Zebras Fix What Unicorns Break, by Jennifer Brandel, Mara Zepeda, Astrid Scholz, and Aniyia Williams