Ifeoma Ajunwa: Thank you very much, danah. With that, I want to say thank you all for coming. I also want to briefly give a special thanks to danah, to Eszter, and to Seth, who all made my being here possible today. I’ll be talking with you today about genetic coercion. It’s a sociolegal concept that I’m still developing and for which I would appreciate and love your intellectual pushback.

The mere existence of a [genetic] technology contains an implicit coercion to use it…Sometimes the coercion is more than implicit.

Lori Andrews, bioethicist and law professor, Future Perfect: Confronting Decisions about Genetics

So in thinking about genetic technology, we have to think about what it means to have it and what that implies in terms of social attitudes and also legal implications. Chromosomes were first discovered in the late 1800s, and by the early 1900s, inherited disease had been linked to chromosomes. After Watson and Crick—and let’s not forget Rosalind Franklin—discovered the molecular structure of DNA in 1953, this bolstered the already-present social belief that the workings of the human body could be summed up through genetic information. And this spurred the development of genetic tests. I argue that genetic testing as a technology, as it becomes more accessible, there’s an attendant genetic coercion prodding American citizens the relinquish their genetic data in the name of the social good.

So what do I mean when I say genetic coercion? I define it as the overwhelming economic, social, and moral compulsion to scrutinize and police the genome that an individual experiences. And to be sure, we have to really break that apart. What do I mean by economic compulsion? Well, this derives from the lack of universal healthcare which renders life that is infirm or frail financially difficult to sustain, and the social compulsion that stems from the reification of genetic data as the key to social life such that non-conforming genes must be exposed. In The DNA Mystique, the authors illustrate the high social value now accorded to DNA. And I quote,

As the science of genetics has moved from the laboratory to mass culture, from professional journals to the television screen, the gene has been transformed. Instead of a piece of hereditary information, it has become the key to human relationships and the basis of family cohesion. Instead of a string of purines and pyrimidines, it has become the essence of identity and the source of social difference. Instead of an important molecule, it has become the secular equivalent of the human soul.

Dorothy Nelkin and M. Susan Lindee, The DNA Mystique: The Gene as a Cultural Icon

So what does this mean in the context of genetic coercion? Well, if the DNA is a secular equivalent of the human soul, then the moral compulsion stems from the idea of genetic hygiene for the betterment of society. It is a moral duty of the individual to scrub from her germline deleterious genetic mutations that would be passed down to future generations. This idea is not a new one. In fact, it is directly linked to America’s eugenic past.

We have seen more than once that the public welfare may call upon the best citizens for their lives. It would be strange if it could not call upon those who already sap the strength of the State for these lesser sacrifices, often not felt to be such by those concerned, in order to prevent our being swamped with incompetence. It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind. Three generations of imbeciles are enough.

Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Buck v. Bell, 1927

The sentence “Three generations of imbeciles are enough,” is a well-known one in American law, and it is found in the Supreme Court opinion written for the 1927 case of Buck v. Bell. This case effectively legitimized the eugenics movement in the United States. In it, the Supreme Court ruled that it was lawful to forcefully sterilize, on a massive scale, persons deemed socially inadequate to bear children. Unfit persons included the poor, the illiterate, the blind, deaf, deformed, diseased, orphans, ne’er-do-wells, homeless, tramps, paupers, as well as criminals and the mentally insane.

The tendency to be unemployed may run in our genes.

Richard Herrnstein, Harvard psychologist and co-author, The Bell Curve

Following with this idea is the rise of genetic explanations for social behavior. So that case was a 1927 case, however Troy Duster in his book Backdoor to Eugenics has actually found that there have been subsequent waves of a rise of genetic explanations for what had previously been considered social behavior dependent on the environment or other factors.

So for example, he found evidence that between 1976 and 1982, there was a 231% increase in asserting a genetic basis for crime, mental illness, intelligence, and alcoholism. He also found that from 1983 to 1988, there were articles asserting a genetic explanation for crime and also unemployment. In fact, Richard Herrnstein, a Harvard psychologist who later went on to write the infamous Bell Curve with Charles Murray, preferred that there could be a genetic explanation for unemployment, not just merely social factors.

Where does the roots of genetic coercion come from? Today, genetic coercion does not speak in the thunderous language of eugenics, shouting about criminal nature or racial inferiority. Rather, it gently whispers the rhetoric of personal knowledge and agency. We are told that genetic testing affords knowledge and also the power to act. Yet, we should ask to whom does this power truly fall? In The History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault notes biopower is governmental power over other bodies. It is an explosion of numerous and diverse technologies for achieving the subjugation of bodies and the control of population. Therefore biopower, when applied to the phenomenon of genetic testing, speaks to the government’s interest in fostering the health of its population. And also in regulating new life, particularly when such life might be deemed burdensome to the state. Thus, we must remember that while genetic testing is most frequently framed in positive terms as life-promoting, it is also life-limiting because it seeks to promote only certain kinds of life, life that is deemed healthy and useful to society.

Genetic testing most frequently is enlistment of the individual citizen as an agent of the state in policing her own bios. So what do I mean by that? For one, genetic testing is presented to African-Americans as a way to discover your roots, so genealogical testing. It is also presented to Jewish-Americans as a way to discover if you carry the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutated genes for breast cancer because this will give you greater agency to make choices that might affect your future risk of the disease. And as we saw in the case of Angelina Jolie Pitt, such testing does prompt life-changing actions, such as surgery to remove the ovaries or the breasts.

So what is the promise of genetic testing, however, when it comes to future generations? I want to quickly show this video.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lP1cCjBkWZU

Essentially you see that genetic testing and the attendant relinquishment of genetic data is presented as something you do for the greater good, right, to perfect the next generation. It’s still you, just a better you.

So with that, let’s think about all the ways that our genetic data leaves us. What are the genetic data streams? You have genetic data leaving us for genealogical purposes like I mentioned, like for example African-Americans seeking what are called “roots” search. We also have genetic testing for health predictive reasons. So, 23andMe has its health predictive kits, where it can tell you your probability of risk for certain diseases such as Alzheimer’s, for example. You also have genetic testing for reproductive purposes, where people engage in genetic testing prior to getting pregnant.

And then you have prenatal genetic testing where, for example, women of “advanced” maternal age (by which they mean anyone over 35) experience social pressure and also pressure from the doctors to engage in genetic testing to detect chromosomal abnormalities for their children. We also have newborn genetic testing, which is mandated by the state. So in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, the law says that once a child is born, that child must be subject to genetic testing to detect both hereditary and congenital defects. Which yes, this is useful because for example there’s PKU, which is a condition that can kill a child shortly after birth if not immediately detected and which is very correctable. And such testing does enable for that to be corrected. But you still have to ask…basically the newborn is forced to relinquish his or her genetic data at birth without their consent. Their parents make that consent for them.

And the newest stream of genetic data is now actually workplace wellness programs. So what are these? Workplace wellness programs are programs in the workplace really for the primary goal of reducing healthcare costs of the employer and also boosting productivity by creating a healthier, fit work body. But the problem is that workplace wellness programs, because they have been pitched as essentially promoting the health of employees, they enjoy great support by the government such that the government allows certain exceptions to laws that exist. For example, a new law that came out through the EEOC is that workplace wellness may collect genetic information via family medical history from employees, without violating the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. So workplace wellness is now another way for your genetic data to get out.

And then finally we have to situate genetic coercion within the mythology of Big Data. And what do I mean by that? As danah boyd and Kate Crawford have observed, there’s a mythology attached to Big Data, and that mythology is,

the widespread belief that large data sets offer a higher form of intelligence and knowledge that can generate insights that were previously impossible, with the aura of truth, objectivity, and accuracy.

boyd, danah and Kate Crawford. (2012). “Critical Questions for Big Data: Provocations for a Cultural, Technological, and Scholarly Phenomenon.” [draft PDF at danah.org]

Genetic coercion is similarly situated within that sort of mythology. The mythology of genetic coercion is thoughts that genetic data, especially large-scale genetic databases, have the ability to pinpoint certain risk of disease. They provide agency to act to prevent such disease, and it can be used to create accurate personalized treatment for disease, and it should also be entrusted with the authority to dictate the modification of the genome for future generations.

And as we have seen in the cases of both the UK and China, this second part has already been acted upon. As you may all know, the UK recently passed a law allowing for three-parent children. It was with the goal of essentially eradicating diseases from the germline. And China has recently conducted experiments using CRISPR, which is a gene-editing tool in which they basically went in and modified the germline of an embryo.

Perhaps I should explain what I mean by a germline. What I mean by a germline modification essentially is when a modification is made within a gene such that that modification will be passed on to any subsequent offspring and not just present in the specific individual that had the gene modified.

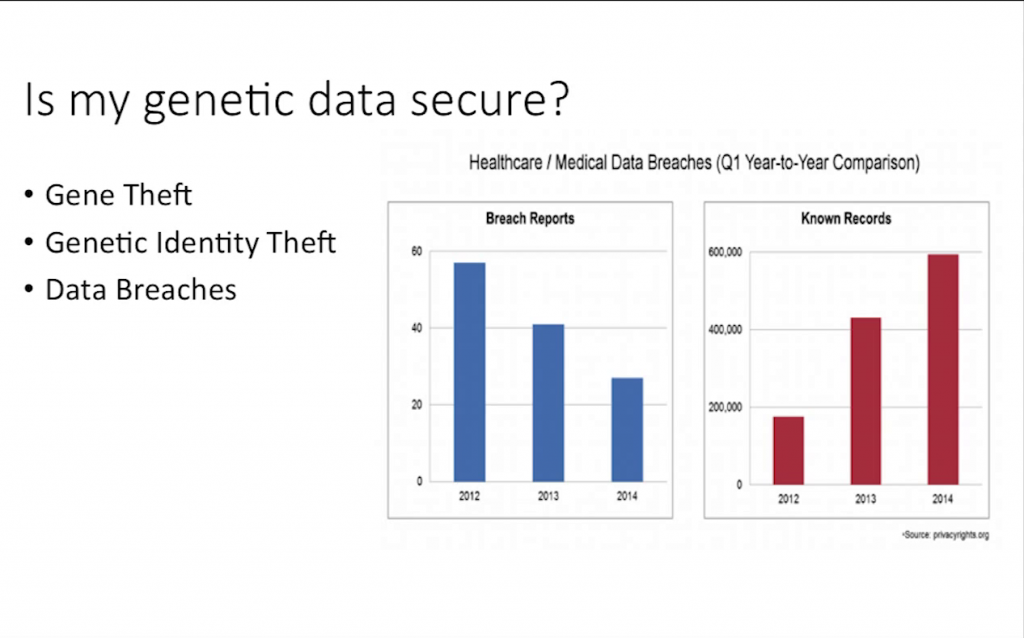

With all these ways that our genetic information leaves us, all these streams of genetic data, we should ask, “Is my genetic data secure?” Well, the alarmist answer would be a resounding “no.” But the more accurate answer is probably, “I don’t know.” And ignorance is not bliss. So as you see here, these are the reported data breaches for health and medical care data for 2012, 2013, and 2014. However, what you see here [is] what is actually known. So there’s actually more data breaches than are actually reported. So that should give you pause because you might think, “I haven’t heard anything. My data is all good.” Maybe, maybe not. And as I say, ignorance is not bliss.

And we should also be wary particularly of the large-scale collection of genetic data from newborns, because there are no hard and fast rules as to what happens to that actual genetic matter. It’s just a speck of blood that usually taken, but anybody with genetic knowledge knows that speck of blood is a lot. It contains a lot of information. And there’s no hard and fast rules as to what happens to that speck of blood. There’s no hard and fast rules to ensure that it’s destroyed after genetic testing, or that it is accurately or securely secured from data breaches. So we should be concerned.

I also did want to mention gene theft and genetic identity theft. Gene theft is actually not against the law. What does that mean? It means if I drink from this bottle and leave it here and I exit, you are perfectly within the federal law (some states do now have laws) to take this bottle, send it to a genetic testing company, and discover my full genome. So gene theft is actually not a federal crime in the US. It is in the UK, but in many jurisdictions all over the world and including the US it is not.

Genetic identity theft is also something that’s on the rise. This might sound futuristic to you, but it’s actually a fact. Researchers in Israel have discovered that it is possible to, just by knowing the code, not having any genetic material from a person, but just knowing their genomic code, to create material that mimics that person’s genetic material such that that material can be left at a crime scene, leading investigators to believe that a different person committed a crime than actually did. So this is reality. And then of course there’s the data breaches that happen frequently. Anthem is a healthcare insurer that just announced a major data breach. And it is worth noting that electronic health records are actually the most lucrative data for data thieves. It’s actually more lucrative than credit card data.

So why should we care about genetic data security? Well, genetic data security does have implications for both privacy and discrimination. From the privacy aspect, we have to recognize that there still is social stigma towards disease, particularly cognitive diseases. Much research has been done to show that there is especially a stigma attached to Alzheimer’s such that people who have been “diagnosed,” which is probably not the accurate word but have been discovered to have a propensity for Alzheimer’s… Note they’re not suffering from Alzheimer’s, they just have the propensity for future disease. Those people actually experience stigma, even before displaying signs of the disease. So that is one of the reasons why we should care about privacy.

We should also care about privacy in the context of discrimination. In one of my law review articles, I talk about healthism in the United States. That is basically the fact that the employer is a major health insurer for most Americans, [meaning] that the employer has a vested interest in excluding from considering for employment those individuals whom the employer deems as costly for its healthcare costs. So this can open up individuals to employment discrimination when they’re found to have genetic disease.

You might be thinking, “Don’t they have laws for this? This is America. We have so many laws, we must be protected.” Well, they have laws, but the laws are not as protective as you might think. So I’ll start with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). The common social perception is that HIPAA protects your medical information. The common perception is that if you go to your doctor and you tell them anything about your health or they do tests on you, that information is iron-clad protected.

Not so fast. HIPAA is actually not a privacy protection law. The main objective of HIPAA was to allow you to take your information from one doctor to the next, from one insurer to the next. That’s really the main objective of HIPAA. As such, it doesn’t really protect your privacy in the way that you might imagine. For one, there’s only a very limited circle of covered entities. So really only medical care providers are protected. What does this mean? Genetic testing companies are not covered by HIPAA; they’re not medical providers. Also, you have to actually ask what the provisions of HIPAA are. And the provisions of HIPAA are thus: Your medical information can be released for the purposes of both treatment and payment. So as you see, your medical information can and will leave your doctor’s office primarily to go to health insurers. So the Anthem breach that just occurred…I guarantee you there was also genetic information that was derived from that by the data breach. So we have to keep that in mind, that while there are laws, they may not be as protective as we might think.

Also, you might say, “Well there’s the Americans With Disabilities Act.” As Americans, unlike some other countries, we care about disabled people. We care about protecting their right to work, to socialize. Well. We do. But the problem is genetic disease which is not manifested is not considered a disability. So for the Americans With Disabilities Act to actually apply, you have to have a manifest, physical disease that is disabling. So for example, if you have the sickle-cell trait but you don’t have the crisis that somebody suffering from full-blown sickle-cell disease has, you’re not covered by the ADA, albeit that you may experience the same stigma and discrimination.

And finally we come to the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act. GINA to the rescue. Now, what does GINA do? GINA is the newest among all these laws, and GINA was an attempt by the federal government to protect our genetic information. So GINA is explicitly both an anti-discrimination law and a privacy law. Title II of GINA says that your employer cannot use your genetic information to discriminate against you for employment, hiring, or promotion purposes. However, GINA has many many loopholes. For one, you actually have to prove that your employer has discriminated against you. GINA does not allow a disparate impact provision.

GINA also protects you against having your health insurance denied on the basis of the fact that you have a genetic propensity for disease. However, there’s also a loophole there. GINA only applied to health insurance. It does not apply to long-term care insurance, disability insurance, or life insurance. So if you take a genetic test and you find out you have Alzheimer’s and somehow this information gets out to insurers, you might find yourself unable to procure life insurance. And this would be perfectly lawful.

Finally, how do we go about protecting our genetic data? This is a hard question. It might not be for you computer scientists. It might not be NP-Hard, but I’ll call it quantified self hard. It is a difficult question. Because while technology might seem like the obvious approach, data breaches are so ubiquitous that we really have to think about really how we go about securing data such that we don’t lose the accessibility because genetic data is useful and some people might want to share their genetic data either for research purposes, for creativity purposes. But they might not want it to be used against them when they’re trying to apply for a job or get insurance.

So how do we protect genetic data while also maintaining accessibility for all the useful things it can do? Well, one of the solutions that have come out is a system of locks and keys, wherein genetic information may be stored in a database. And in that database, people can have access at varying levels of access based on a system of locks and keys. So for example, your genetic data can be in a database and then you can allow access for say, a research university to study a particular allele of your genome to cure Parkinson’s. But that university wouldn’t have access to your entire genome. They would just have access to that allele and perhaps the way information from you in terms of things like your daily life, the way you exercise, your eating habits, etc.

So that’s one option in terms of giving limited and particular and specific access. But it still entails having your genetic data in a database, and there are still issues there. So I can’t claim to have a solution to this. I would love if some of you do.

I don’t necessarily advocate for more laws, because as we have seen, we do have laws. The problem is that there are so many loopholes within the laws that we already have. What I do advocate is perhaps strengthening some of the laws that we do already have, in particular GINA. If we can strengthen GINA with a disparate impact provision clause, I think this will help in terms of the issues of employment discrimination that can arise from genetic data breaches.

I also think education is key. Educating both the general public and the government about what general information really is. Its utility, but also its limitations. Recognizing that it’s not really the panacea that it is presented as perhaps by companies seeking to make a profit from it.

And finally, I want us to think about what are the seeds for future research. I particularly am interested in learning about American beliefs and attitudes regarding genetic data. How has this changed over the years, and what accounts for these changes? For example, what is the extent of scientific knowledge that your average American holds regarding genetic data, and how does this influence consumer behavior? What are issues regarding the use of genetic data in personalized medicine, both ethical and legal? What are the ethical issues regarding the sale of genetic data, especially considering that your genetic data is not just you; it’s also all your future generations. Do you really have the authority to make this sale, or to even publicize your genetic data in this way?

So with that, I want to thank you all for coming, and I look forward to your questions and comments. Thank you very much.

Audience 1: Hi. Thanks, Ifeoma. That was super interesting. I have a question for you about kind of the intersection of genetic data and behavioral control. I’ve been noticing in the news lately several cases in which DNA is used, not really because we’re interested per se in the genetic information that it contains, but DNA testing gets used to identify somebody who’s accused of some sort of wrongdoing. So I just saw last week there’s a case in which a waiter in Syracuse, New York spit in a drink, and the police tested his DNA— I mean it’s maybe overblow, but the police tested his DNA and charged him with disorderly conduct based on a match between the spit and him.

And then there’s a case I think pending in the Ninth Circuit where these employees were leaving piles of feces around. Do you know about this case?

Ifeoma Ajunwa: The “devious defecator.” [crosstalk] It has become known as the devious defecator case.

Audience 1: The devious defecator case, yeah. Which I think the employees weren’t the devious defecators, but I’m pretty sure (you know more about this than I do), but I’m pretty sure they’re suing under GINA.

Ajunwa: Yeah, they did sue under GINA.

danah boyd: Could you tell us more about the case?

Ajunwa: Yeah. So, it’s a really funny case. I think they were working in some sort of warehouse, and somebody was leaving piles of feces around the warehouse. And the employers decided that the best way to discover who was doing this was to test their employees. But they didn’t test all the employees, which is also an interesting part of the case. They decided that it must be a group of people, and only tested those people. They essentially forced them to give up their genetic data.

It turns out it wasn’t actually them. But that didn’t matter, because those people being singled out to be tested, actually that exposed them to ridicule by their coworkers, and it became a hostile work environment for them, essentially. But they brought suit under GINA, which technically isn’t what GINA was really anticipating, I would think. But it worked, because that was a clear case of an employer requesting genetic data from an employee, in terms of, “If you don’t give us your genetic data, you wil be fired.”

Going back to your question, yes, there has been a significant rise in genetic data being used for crime-solving purposes. A colleague of mine at my law school, actually, has written an article called “Predictive Policing,” and it’s basically the idea that policing now is more about prediction than actual entrapment or actually catching the person red-handed. It’s more like predicting who did it.

Because what we still need to understand it that DNA is still a prediction. It’s just saying, “I predict, to this level of probability, that this is the person that did it.” So there is a rise in that. And in fact, an interesting part of that rise is the use of DNA for phenotyping. So there was a case where genetic data was left at a rape crime scene, and the data was used to decide what the rapist might look like in terms of skin color, height. And that led to sort of narrow[ing] the field of who the suspect could be.

So there’s a rise in that, but there’s also obviously a rise in scientists calling foul because genetic data, particularly for phenotyping, is highly fraught. Because in terms of for example skin tone, there’s actually hundreds of genes that actually affect skin tone, and that interacts also with environment and diet, etc. So, you can’t really be quite accurate with that. Hopefully that answers your question.

Audience 2: This is quite fascinating. Are there any legislatures, either at a state or in the US or outside of the world, that have taken on these issues to be the example that US should be looking at?

Ajunwa: Well, I think the US should definitely look at the UK in terms of what is called gene theft. Currently (and I’m talking federally, because California for example does have laws against gene theft) the US has a position that it takes of “abandoned DNA.” So if you spit out your gum in public or you leave a cup that you drank from at a restaurant, that is considered abandoned DNA such that for anyone to take that genetic material is not gene theft.

The UK actually has a blanket ban against gene theft. And can I tell you why they do so? I’ll tell you why. So, in the early 2000s, a journalist came out with the story that Prince Harry, as he’s called, is not the son of Prince Charles. And there was a theory that he was actually the son of a butler who had worked there with whom Princess Diana had had an affair. And there was concocted a plan to steal some of Prince Harry’s DNA in order to test it against the butler, who was cooperating, to determine if he was indeed the butler’s son. So that is actually why the UK has a blanket ban against gene theft.

Audience 3: It’s sort of a dumb question, but is sperm considered abandoned DNA?

Ajunwa: Oh, I love that question. So uh, yeah. I love that question. I’ll give you several cases. Oh, man. I love that question. [laughter] Because there are so many cases, so many stories, I’m just trying to see which one I should pick.

The first one I’ll start with is this. There was a case in which a man received oral pleasure from a woman, and the woman collected the sperm and subsequently used that to inseminate herself. And the woman then later sued him for what? Child support. And the man filed a counter-suit for fraud and theft, saying that she stole his sperm. Well, that case was adjudicated as not theft. He was deemed to have made a gift of the sperm. So there’s that. That’s the story now.

Audience 3: But would that apply in the UK scenario?

Ajunwa: So, in the UK scenario that perhaps would have been deemed gene theft, because you could say he wasn’t giving it to her for the purposes of later inseminating herself. But in the American scenario, it was a abandoned DNA for her to do as she pleases. Or more importantly, actually, this case really was a gift, for which as it is a gift you can do whatever you want, right?

Audience 4: I wanted to ask about what you thought about disparate org—like, there’s privacy by design. Ann Cavoukian, she advocates okay, organizations can collect as much data as they want as long as privacy is set as a default setting. Then there are tech companies that are making sure that organizations have a least privilege model. So you have different organizations or just people doing different things. I kind of feel like they need to talk to each other more, and just there are bits and pieces of like, app developers who are really interested in the technology and it’s not that they don’t care about privacy, it’s not something that they’re thinking about. How do we just address— I mean there are— I don’t want to sound so gloom and doom because there are so many things to be worried about. But there are people and organizations that are working on that. I wanted to hear your thoughts.

Ajunwa: I think that’s a really interesting question because there’s the idea that we should all become Facebook with our genetic data. And some people have actually put this in practice. There is a man who has a Facebook for genetic data. So you can join with your genetic data, and it’s open to everyone in the network, and it’s for artistic, creative expression. But this idea of privacy by design, I don’t buy it. Just because there’s just too many instances of data breaches. And even if it’s not from without, it can come from within.

Audience 4: But there are organizations… I work at a data security company, and they are trying to sell the least privilege model and auditing everybody’s data access and that you shouldn’t get access to stuff you don’t need. And that there are companies that do that and that there are people working on it, I just kind of feel like who should be the data owner when it comes to our own personal data.

Ajunwa: I think that that last question is still really the most pressing one. Who should own your data, right? So, 23andMe recently brokered a deal where all the genetic data it collected from its clients who had checked the box for research, it was able to sell for like $60 million. And the question is, should the clients then get some of that money back, right? Because when they clicked the box for research, were they giving it up altruistically like for public research? Or were they really giving it up for private research of the kind that 23andMe me is basically selling it for?

So those are unanswered questions that remain. I can’t claim to have the answers, and I think it’s definitely things we should continue to think about as we engage in genetic testing, for sure.

boyd: I’m going to take moderator’s privilege for a moment. One of the things I struggle with whenever we talk about the privacy by design issue or about these questions of individual control is genetic material is one of the most beautiful example of material for which it’s not clear who the owner is because it’s network data. The information that is “your” genetic material to theoretically give out or to have exposed in different ways fundamentally affects your children and your not-yet-living grandchildren.

Ajunwa: Exactly. And your living relatives.

boyd: And people you don’t know. So one of the things that’s been happening in the LAPD is that they’ve collected a massive database of genetic material, and they’re going and looking for suspects’ relatives.

Ajunwa: Familial matches.

boyd: Right. But the thing is they keep showing up at the doorsteps of people that don’t know they have had siblings.

Ajunwa: Exactly, exactly.

boyd: And so one of the things that I think is another ethical consideration for all of this, and a technical, a legal, a social, is how do we account for the people who effectively have no choice because they’re related to the people who theoretically “have” choice? And how do we reframe or think about those networks of responsibility with regard to the privacy, ownership, and our responsibility outlet?

Ajunwa: It’s something I’ve given a lot of thought to, particularly in the context of 23andMe, this wholesale…basically transfer of genetic information to a corporate entity. And I feel fairly certain that many of the people who checked that box, they didn’t do so knowingly. They might have done so voluntarily, but in contract language you have do something both knowingly and voluntarily. And “knowingly” means you understand the full repercussions of when you sign that contract. And for the 23andMe me case, I suspect that several of the people who signed that, they didn’t understand that this means your genetic information, your children’s genetic information, your grandchildren’s genetic information, your mother’s genetic information, can end up within a corporate entity, or several corporate entities, for whatever purpose. And that’s the thing. They don’t even have a say in the purpose of that genetic information and how it’s used.

So I think it’s a really weighty question. Because it is a network issue. So it’s not really so much an individual privacy, personal agency, issue the way it’s presented by the genetic testing companies. Some of the ways I’ve thought about it is what I mentioned earlier about allowing access to genetic data but for limited portions or for limited uses. So you could, for example, be allowed to sell your genetic data to a corporate company, but only for your lifetime, such that after your lifetime they would have to destroy both the matter that they have and the information that they have, and then they would have to ask for permission again from your descendants if they wanted to continue using that data. So that’s one way. But it’s a very weighty isssue, and one that needs serious thought.

Audience 5: Fantastic talk.

Ajunwa: Thank you very much.

Audience 5: Just with your sort of seeds of future research, I wanted to…maybe you can speculate a little bit. You mentioned that you want to start looking at the sort of trends or American attitudes toward genetic testing. What do you think you’re going to find, and does anything scare you, particularly because you know so much about the history of eugenics and such. Do you see a sort of resurgence of that? And then maybe just a second one. You talked a little bit about comparative attitudes, UK versus United States, is there any country do you think that is doing it really well or really far behind?

Ajunwa: I smile when you say “speculate” because as a social scientist I’m not allowed to speculate. But as a science fiction afficionado, I will speculate. I suspect that most Americans have very low scientific knowledge of genetic data and what it really means, and what it is to begin with, and what it can do, and what it cannot do. I suspect that most Americans, if they have any knowledge of genetic data, it’s not from schooling, it’s from advertisements. It’s from the things that the corporate companies are telling them genetic data can do, a lot of which are hyperbole. You can have hyperbole in advertising. But a lot of Americans don’t necessarily have the scientific tools to be able to separate the hyperbole from the science fact.

So I suspect that as a result of this, there will be more and more genetic testing. More people are going to say, “Sign me up. I want to know my exact risk of Alzheimer’s.” Which, frankly, isn’t really what you’re getting. You’re getting whether you have the gene that could cause Alzheimer’s. But you’re not really going to get your exact risk. Because that depends on so many other things. Your environment. The kind of job that you do. Your social life. Your diet. If you do brain exercises like Lumosity. I mean, it [depends] on so many different factors. But I suspect that the average American is seduced by the promise of genetic testing, and as a result there will be more and more.

And also, there will be more and more of a eugenics bent to it. Right now it’s presented mostly for finding disease and preventing disease. That’s the language now. But I believe that later on, the language is going to go more towards [what] you see in Gattaca, which is creating the perfect baby, creating your ideal baby, creating the baby that reflects the best of you. So I think that’s the wave of the future.

Audience 6: My question actually sort of ties into what you said before. I was wondering how do you see insuring, or answering the question who has the responsibility to insure that there is informed consent on the part of whomever is opening their genetic data. There’s for instance a case we had in the Netherlands, where I’m originally from, is that we tried to establish this thing which is called “the open patient dossier” where everything would be digitized. So if you were to have a heart attack in one city and the doctor didn’t have your prior medical records, they could get them really easily. And there was a lot of pushback on this, specifically for the examples that you mentioned: data breaches, it’s too easy to procure, etc.

So one of the things that was extremely effective in the campaign against this dossier is saying that well, we’re going to make the GPs partially responsible for anything that goes wrong. And if they haven’t informed their patient well enough that it’s partially on them. Which led most GPs to actively discourage their patients from signing up—

Ajunwa: I can imagine.

Audience 6: —because if they make a mistake that we can’t control, not only are you in an unpleasant spot, but so are we. So I was kind of wondering how do you see that debate taking place here. Who should have that responsibility to ensure that there is real informed consent, because as you just said you can’t expect people to know not even just the genetics of this but the intersection with all the different things. It’s impossible.

Ajunwa: That’s a really great question because the funny thing— There was a survey done in 2011, and it found that actually 85% of doctors had never heard of GINA. So if that’s who you’re relying on to tell you about genetic data protections, you’re going to be at a loss. So I frankly don’t think the burden should be on the doctors. I think the burden is on the government. Because the government is having these laws like the newborn testing law, that’s requiring, coercing people to relinquish their genetic data. And as such, the government then has a burden to protect that data, and also to educate people about how they can go about protecting their data even beyond that.

So I think the government has a duty to educate all healthcare workers, not just doctors, nurses, everyone, about genetic data, and also the protections of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act, and its limitations. Because one thing that happens is that Americans think, “Oh, there’s a law on that. I’m protected.” And that’s not entirely the case. So it’s also about educating about here’s your rights under the law, but also here are the limitations of the law, just so you can give informed consent.

Now, some of the people who signed up for 23andMe, maybe they had vaguely heard of GINA. And maybe they knew it prevented your employer from getting your genetic information. But did they know, for example, that if by signing off at 23andMe and discovering that they have Alzheimer’s they now may no longer be able to buy life insurance? Did they know that? And if they knew that, might that have changed the decision? So that’s why I talk about knowing consent. They voluntarily gave consent, but was it really knowing?

Audience 7: Thanks a lot for this discussion. This is really interesting. I had a specific question. You mentioned that stolen genetic data is worth more than credit card data. Could you talk a little about the market for stolen genetic data?

Ajunwa: Usually the stolen genetic data is not the most targeted. They’re targeting medical records, which will contain some genetic data. So it’s actually medical records in general that are the most lucrative as opposed to credit cards, etc. And the reason why is this. People basically use it to impersonate you and use your health insurance. So for example, getting access to your medical record, a person can sign up to have surgery that’s like $300,000 surgery, for example. Whereas with your credit card they might be able to get $2,000 before you cancel it, or something like that.

Audience 8: Very interesting talk. At the beginning you sort of mentioned universal health insurance and its sort of notions of participation. So my question is, obviously the LAPD is collecting caches of data, or the FBI’s collecting caches of data in the course of their police work. Then the DNA databases they have reflect the police practices they engage in, which many of us might agree are discriminatory. If there were a different kind of level of participation in giving up genetic information, would that change the way you think about the problems surrounding genetic privacy, and—how would that change the kind of talk you might give about this?

Ajunwa: Okay. So I guess to understand your question, you’re saying if the genetic databases were voluntary and maybe open…?

Audience 8: This might raise a whole bunch of other problematic issues, but imagine a world where everybody had to have their DNA on file. Everybody.

Ajunwa: I do imagine such a world.

boyd[?]: Iceland.

Audience 8: Right. Iceland, exactly. So they do this in…some populations have done this for research purposes. How does that resolve some of these issues or not resolve them? Or maybe it raises new questions that we might worry about.

Ajunwa: I don’t necessarily think it resolve these issues. I think it makes it easier to discriminate. If everybody has genetic data on file, you now no longer have to ask them family medical history, you just go look it up and say, “Oh, I would hire that person but I see they have this slightly elevated Alzheimer risk, so no.”

So in a way it actually would open up a larger can of worms. For me I’m not so much concentrating on the criminal enforcement aspect as I am on the employment and social aspects, where I feel that large-scale genetic collection could actually lead to what you see in Gattaca, because that is what Gattaca is, right? Everybody has their genetic information on file. And with that, certain people are classified as valid and then the others are classified as invalid, depending on the number of genetic mutations they have. So the more genetic mutations you have, the less likely you are to ascend the social ladder, essentially. So you’re relegated to certain jobs. So I don’t necessarily think it’ll solve the problem. I actually think it might exacerbate it.

boyd: Fantastic. I know we’re out of time, but I want to say thank you so much for your invigorating talk. Thank you.

Ajunwa: Thank you very much. Thank you all for coming.

Citations

- Eight Strategies to Engineer Acceptance of Human Germline Modifications

- Untangling the Promises of Human Genome Editing

- A Call for an International Governance Framework for Human Germline Gene Editing

- The Nuffield Council’s green light for genome editing human embryos defies fundamental human rights law