Andrew Hoppin: So you know, I made a slide deck for this presentation. And I made it just for this conference and it’s kind of intimidating to do that for a room full of designers because I’m one of those people that like you literally cannot read my handwriting. So, we’ll see how it goes, and I’ll get over it because I’m really passionate about what I’m here to talk you about today. I’m here to talk to you about trust. And I’m here to talk to you about how I believe we need to recover trust in order to make our world work better for all of us. And more importantly than that, I think the people in this room can do something about it, which is why I’m talking to you about it today.

So, let’s roll back to about 2011. Marc Andreessen famously said software is eating the world. And what I took him to mean from that is that no longer is software an industry, industries are becoming software, right. Like software is everything.

Okay. Now fast forward to 2017 and The Economist popularized an adage “data is the new oil.” Now, I’m not particularly fond of that adage but I think it’s instructive nonetheless. They were saying that data that powers software is the thing that is powerful. And if that power is reposited in the hands of too few, there may be some existential risks that could result from that. And lo and behold I think that that’s what we’re seeing in the world today.

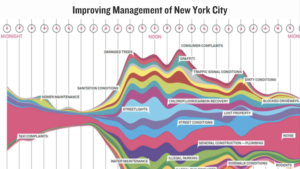

That said, I love data. And as Julie said in my introduction I’ve been working on it for a long time. I like opening up data. I’ve been working in the open government movement for a decade and I’ve had the profound opportunity to do things that I really have seen make a difference, with data, in the lives of the communities that I’ve been part of. I helped New York City to figure out how to better allocate its resources in response to demands from residents and complaints from residents about what they needed in the city. I’ve helped to structure the lawmaking process in New York and make it data-driven and make it machine readable and programmable so we could build user interfaces that could help New Yorkers find out what was going on in the chambers that make our laws and actually get involved in shaping the laws that we live under.

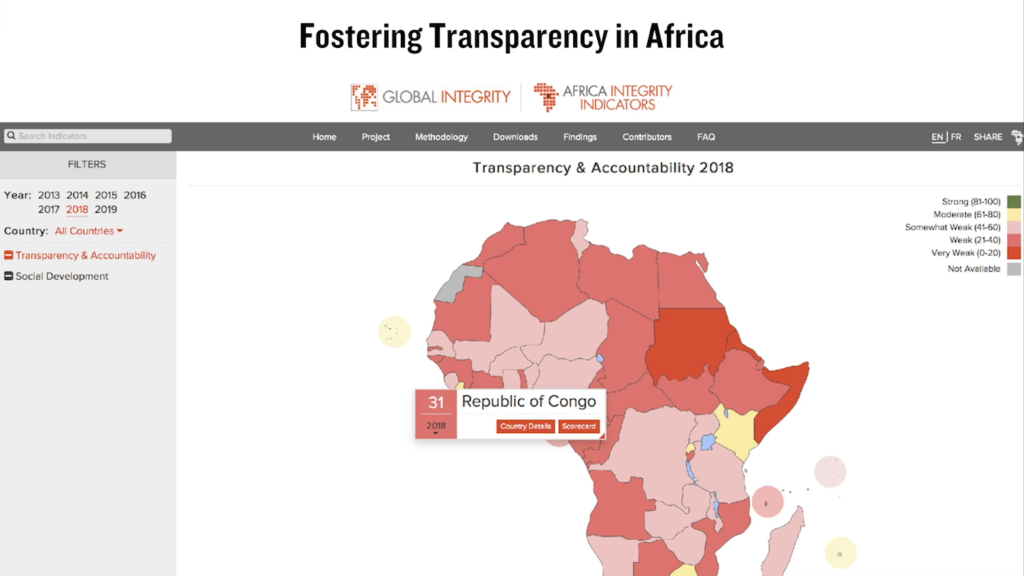

Again, a use of data. I’ve helped organizations that collect data about governments all across Africa and helped to adjudicate which ones are effective and transparent, and which ones are corrupt.

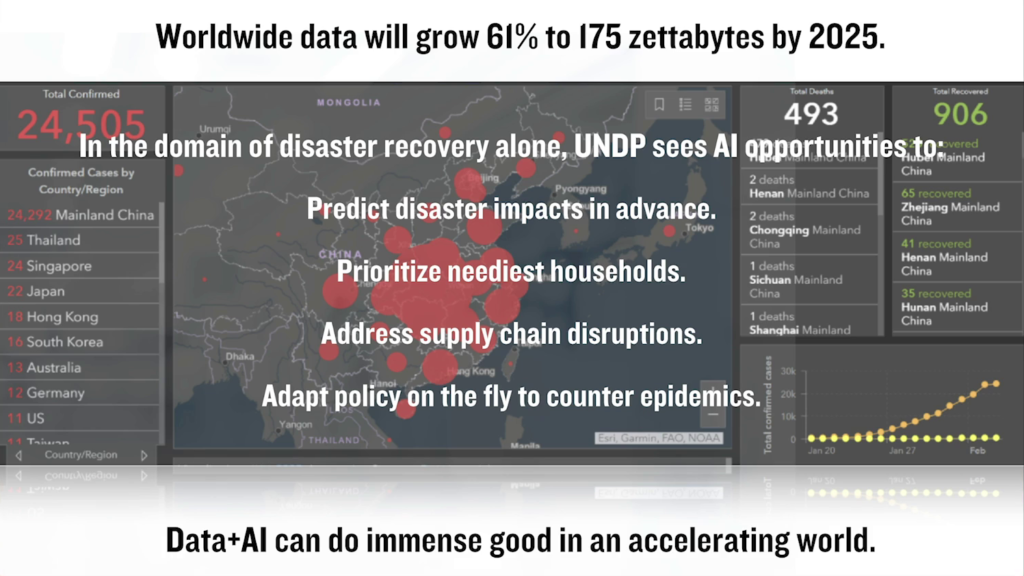

And the power of data has never been bigger than it is today and I think this can be a great thing, even though it is also creating some existential risks. Specifically I think it can be a great thing because not only do we have software which is eating the world, and not only do we have data which is powering or fueling the software, but we have data now driving artificial intelligence or machine learning models. Which are essentially, to oversimplify a little bit, they’re actually iterating the software as we go. So the software’s not only powered by data, the software’s getting better all the time because you’ve got data powering artificial intelligence models that in fact keep the software getting better all the time. It’s profoundly powerful, and so for organizations that have access to the right data—and a lot of data, often—and that have the best artificial intelligence models, they can often make the best decisions. And in many cases, and this is going to grow in proportion over the years to come, better decisions than humans can make. So it’s immensely powerful, right.

And this power can be used for good. I was with the UN Development Program about a month ago talking about how their open data, of the sorts that teams I’ve worked with over the years have spent a lot of time trying to open up, coupled with data about the people and the households in communities that they serve in disaster scenarios could be put together to drive machine learning or artificial intelligence models that could help them to adapt their responses to disasters faster than humans could by themselves. Immense power for good.

But, and here’s the big problem: most of the consumer-driven artificial intelligence work that’s happening in the world today is being driven by your data and my data as consumers. And it’s being used to sell things to us and to manipulate us. By and large, not for good.

Facebook knows what I want to read. Amazon knows what I want to buy. Netflix not only knows what I want to see, it knows what to invest in now that I’ll want to watch in a year. And I like these things. I consume these services. I’m kind of aware that I’m giving up some data for doing it but they provide a lot of utility and value to me. I even like to interact with artificial intelligence chat bots now, over human being customer service representatives, because I can usually get in touch with them faster. 63% of us prefer to interact with AI chat bots for customer service and that ratio’s only going to grow as these artificial intelligence models get better, and better, and better.

So it’s immensely powerful but it’s also immensely risky when it’s being used for this purpose. And it’s not just in this scenario that I kinda know. I’m sharing data with Facebook and Amazon. Okay. Maybe I can make my peace with that. It’s also organizations that I’ve never heard of that are literally buying and selling hundreds of data points about me and about hundreds of millions of my fellow Americans, and even some people here in Europe, without my knowledge. And certainly without my permission to use that data for the purposes they’re using it for.

And this is creating some really dystopian scenarios. It’s leading to discrimination in consumer finance and lending. If I live in a poor neighborhood, even if I haven’t shared my data I may be discriminated against in applying for a loan in the United States. Same thing for healthcare. If I live in a neighborhood with high incidences of cancer, I may be discriminated against in terms of my ability to be insured in the United States because data is driving models that are saying I’m risky.

It’s also famously, obviously, undermining elections and democracy and literally being used to manipulate people. It’s even being used to create so-called deepfakes which are creating representations of reality that never existed that are increasingly impossible to distinguish from reality.

So these are some really dystopian scenarios. So, now if you believe that data is the new oil, let’s stretch the metaphor a little bit. I think that if data’s the new oil, artificial intelligence is the worst kind of oil. It’s like the the dirty coal of petrochemicals, right. And we need to do something about it. And what I think we need to do is I think we need to redesign the personal data economy to optimize not for having the most data, but for having the most trust.

So that’s what I want to talk to you about, is how can we go about doing that. In order to trust again we need power, we need power over our data again. How can we do that?

Well, a lot of folks have said let’s break up Big Tech. They have the data, this is what The Economist was warning us about in 2007, data’s the new oil. Break it up.

Okay. Good idea, maybe. But, I don’t want twelve Facebooks. That would be worse for me than one Facebook, right? I don’t want to have to go to twelve places to go get value from my proprietary data. I’ll be getting less value, and I’ll arguably have even less idea where my data is or what it’s being used for. So if the data stays proprietary, breaking up Big Tech doesn’t help.

What about privacy laws? Well, absolutely foundational. I need rights. GDPR is a great start. Thank you Europe. It’s coming to the US. It’s already basically there in California and I think it’s going to become the rule not the exception around the world. So yes, thank you. But it’s not nearly enough. Because I’m still stuck with a choice between essentially opting out of the system and withdrawing my data, and no longer being able to go find my friends and in some cases even get jobs. Or, resigning myself to the fact that my data’s going to be used, and arguably even abused. So that’s a false choice.

Okay. What else? What about contextual consent? What about if I could say, “Okay, Facebook. I’m okay with you using my data to connect me to my friends. I love that. I’m not okay with you using my data to show me political advertising that’s gonna manipulate me.” Wouldn’t that be great? Well yeah, I think it would be great. We don’t have the technology protocols, let alone the open standards that allow us to describe even what I just described in ways that machines and humans can understand and agree upon to be able to make that kind of nuanced choice.

And it’s not just for what purpose, it’s also what part of my data. I may be happy to share data about my bad leg with my doctor, but not data about my mental health, right. I may want to share data but only for this period of time when I really need something from the sharing of that data. I may be willing to share it with an entity that I trust, but not with that other entity that I don’t trust. Or I may be willing to share it but in exchange for something of value that’s given back to me. I would like to be able to make those kind of contextual consent choices but even if we had the enabling technology protocols for that…I’m busy. I have a full life. I don’t want to wake up in the morning and try to make a new hundreds or even millions of permutations of choices about what is done and what is not done with my data. It’s necessary, it’s foundational, but it’s not practical and accessible for me as an individual.

Okay. So, what about personal data wallets? You know, what if I actually literally took my data back and had custody of it here and not in Facebook’s cloud. Well again, great idea. I think it’s really important and foundational, but there’s still a problem. I may choose to withdraw my data from that system for my own reasons, but what if you don’t? And what if you look like me, what if you live near me, what if you have a similar genetic makeup to me? I’m still subject to the consent choices that you make. And the real point here is that even if we had control over our data, in this perfect decentralized data storage world, we still need to think about collective data governance. Because our data and our choices about our data affect each other.

Okay, so how can we actually practically do something about this? What I’m really excited about is an idea called consumer data trusts. And a consumer data trust would be a new legal entity that I could delegate, as my proxy, all this responsibility to, okay. So it would roll up my newfound rights that GDPR and other privacy-related laws give me; my newfound ability to actually take physical custody of my data in a data wallet or in a local device; my ability to make contextual consent choices about yes, use my data for this but not for that; and it would roll up those new possibilities and those new responsibilities into an entity that had the sophistication to be able to really do that, and that had a fiduciary responsibility to me, not a profit relationship or profit motive related to me.

And so critically it would have that ability to balance the tension between the things that actually want. I want that network effect. I want to be able to find my friends. I want good research to be done that will help develop new cures for new diseases. I want all that. I want big pools of data. I want great AI models that can learn from that data fast. I want good decisions to be made. I just want it to be done in a way that’s balancing this tension between privacy and sharing, and I want to balance what’s good for me as well as with what’s good for my cohort, my community, our society. I think we need a new entity that has a fiduciary responsibility and the technological sophistication to do that.

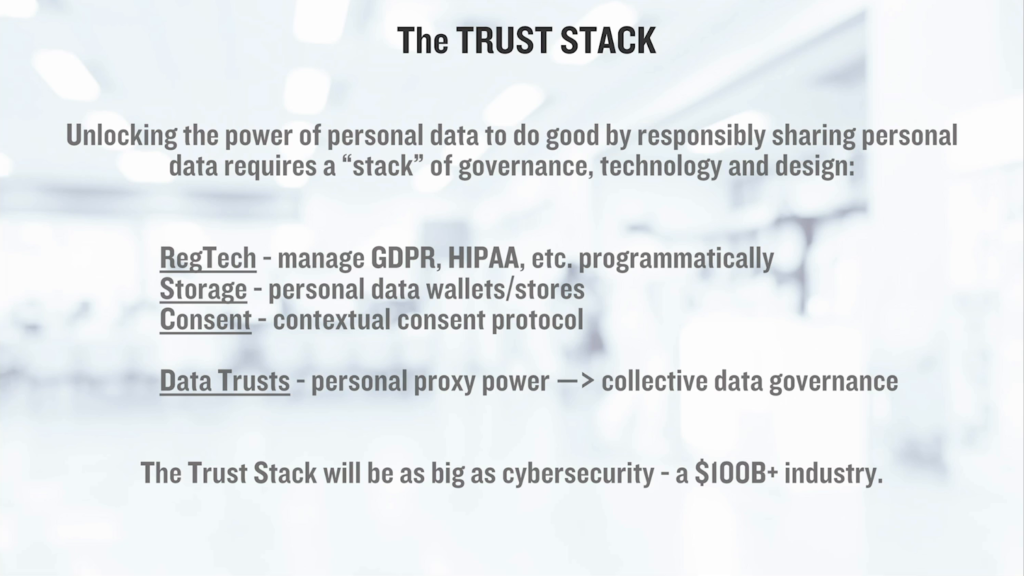

So, how could this actually happen? Well I think it’s really a roll-up of— It sounds really complicated, I know, but I think it’s a roll-up of a lot of things that are already underway. So, RegTech, there’s a lot of great RegTech innovation that helps companies like my little healthtech startup deal with complex compliance issues with regulations, and laws, GDPR, HIPAA, what have you.

Storage tech. There are whole lot of great startups working on decentralized data storage. They’re early, except for you know, one quite notable one—Apple—that I think is doing interesting work in this world as well. So there’s real innovation in storage tech.

And consent tech. This contextual consent protocol that I mentioned is being worked on as well.

So I think really data trusts are just a way to actually take all of these emergent new opportunities and to organize them under an entity who’s gonna have a responsibility to me, not a responsibility to Facebook, not a responsibility to my government, and also a responsibility to us as a society.

And if you’re thinking this is a great idea, sounds great, I’m interested, but I have a job to do, it sounds really complicated? Well…yeah, maybe you should have a job to do. I actually think this is going to be huge new industry. I think the trust stack will be as big as cybersecurity. So if you want a job in this, it might be something to think about.

So where are we in the trajectory of this becoming not just an idea but a reality? There are a number of organizations that’ve done early prototypes of data trusts of various sorts. Some of them don’t relate at all to consumer data, they’re related to environmental and other data, where there are some trade-offs to make in terms of sharing between organizations and an ecosystem that don’t necessarily trust each other. But some of them are working on consumer data. I’m working on a prototype of this with the Global Center for the Digital Commons in health data, for example.

And the real key message is I think the time is now. I think we need this, and I think as I said at the beginning, the people in this room can do something about this. If you value trust, I think you can help us make trust something that is valuable again, okay. So, I would like you…or I invite you, between now and the next Interaction Week, to go into your organization and look at where you could potentially prototype a data trust. Doesn’t need to be all-encompassing, doesn’t need to be all your use cases, all your data, all your users. But find one you think might be well-served by a data trust. And if you’re not sure how to go about it call me up and I’ll help you.

I think if a number of us go off and do this, we’ll make great strides, even in just the next year, from moving from a metaphor that I don’t much like: data is the new oil, to a metaphor that I like a lot: trust is the new power. Thank you.