Ethan Zuckerman: One of our ambitions for this conference is a minimum of one lawsuit per panel, so we’re off to a very good start here. And perhaps trying to keep this in the same tone, Cory mentioned legendary security researcher Bunnie Huang. He’s going to be taking the stage next. You may know Bunnie from his time at MIT, where he was both a hacker in the MIT sense, and a hacker in the much broader sense, including some really groundbreaking work on reverse engineering on the Xbox; one of the world’s leading hardware hackers. He’s also going to be talking with another hacker legend, Edward Snowden, who is going to be joining us via video to talk about a project that they are working on together. So, Bunnie and Edward.

Edward Snowden: This is the first time that I’ve given an actual academic talk. This is exciting. One of the interesting things about Cory’s talk—it’s great to follow him up—is that he brought up an idea that is great for this form because it’s something we don’t talk enough about, which is the idea that laws are actually a weak guarantee of outcome. We outlaw murder, we outlaw theft. They still happen. We outlaw many other behaviors, they still happen. This is not to say they’re bad. This is not say we don’t want any rules. But there are better guarantees. And we should consider when they are appropriate and when they in fact can provide a greater enforcement for individual or human rights. Then the actual laws are policies themselves left naked and sort of [belong in the world?].

So let’s let’s get started with the talk. A quick introduction. My name is Edward Snowden. I’m Director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation. Some years ago I told the truth about a matter of public importance, and as a result a warrant was issued for my arrest and I’m no longer able to travel freely. But today is a great example of why that doesn’t mean exactly what it once did.

And because of that, I’d like to thank very much MIT for organizing this conference, and the opportunity to speak with everybody here today. For journalists in the audience, that’s not a small thing. I should point out that they deserve credit for living up to that commitment to knowledge.

Now, no organization is perfect. Everyone makes mistakes. But that is quite a risk. And this may be the first time an American exile has been able to present original research at an American university. So it’s hard to imagine, I would say, a more apt platform for this talk than the Forbidden Research conference.

But that’s enough preamble. The guiding theme of many of the talks today, I think, is that law is no substitute for conscience. Our investigation regards countering what we’re calling lawful abuses of digital surveillance. Lawful abuse, right, what is that? It doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense. It seems like it might be a contradiction in terms. When I announced the talk on Twitter, somebody immediately was like, “Lawful abuse, isn’t that a contradiction?” But if you think about it for just a moment it might seem to be a little bit more clear. After all, the legality of a thing is quite distinct from the morality of it.

And I claim no exceptional expertise on any of this, but having worked at both the NSA and the CIA I do know a little bit about what I would consider to be lawful abuses. After all, mass surveillance was argued to be constitutional and yet the courts found very differently despite the fact that it was hidden and was occurring for more than a decade.

Lawful abuse is something that I would define as an immoral or improper activity perpetuated or justified under a shelter of law. Can you think of an example of that? I mean, it doesn’t take long to look back in history and find them, I think. But what about things that are more recent? Mass surveillance, of course, is the example that’s nearest my own experience, but let’s set that aside. What about torture? The Bush administration aggressively argued that torture could be legalized. What about indefinite detention? The internment of individuals for years without access to trial or due process. Extrajudicial killing. the targeted assassination of known individuals far from any war zone, often by drone in today’s world.

Now, they may be criminals. They may be even people who are armed combatants. In many cases, but not all. And the fact that these things are changing, often in secret, often without the public’s awareness or their knowledge or consent, should be disturbing. Given that there are sort of covert legal protections for these engagements. Now, such abuses aren’t limited strictly to national security. And that’s important, right, because we don’t want this to entirely be this big paradigm of politics between sort of doves and hawks. Segregation, slavery, genocides. These have all been perpetuated under frameworks that said they were lawful as long as you abided by the regulations that are sort of managing those activities.

Lawful abuse of surveillance could also be more difficult to spot, not something that’s as obvious. How about a restriction on who and how you can love someone that’s enforced by violence? Or something as simple as an intentional tax loophole. Or discrimination. Lawful abuse.

So we’ve defined the term, right? But what is the actual problem? Well, advances in the quality of our technology, combined with a retreat in the quality of our legal frameworks have created a paradigm in which our daily activities produce an endless wealth of records which can and are being used to do harm to individuals. Including those who have themselves done no wrong.

If you have a phone in your pocket that’s turned on, a long-lived record of your movements has been created. As a result of the way the cellphone network functions, your devices are constantly shouting into the air by means of radio signals a unique identity that sort of validates you to the phone company. And this unique identity is not only saved by that phone company, but it can also be observed as it travels over the air by independent, even more dangerous, third parties.

Now, due to the proliferation of sort of an ancient third-party doctrine-style interpretation of law, even the most predatory and unethical data collection regimes are often entirely legal. And effectively what this means is that if you have a device, you have a dossier. They may not be reading it, they may not be using it, but it’s out there.

Now, why should we care? Even if there are these comprehensive records being created about your private activities, right. Where you are. Who you went with. How long you were there. Did you meet with anyone? So on and so forth. Or were any purchases made. Any sort of electronic activity record, when things are at it.

I can think of a thousand and seventy reasons why it matters. According to the figures of the committee to protect journalists, more than one thousand and seventy journalists or media workers have been killed or gone missing since January of 2005. And this is something that might not be as intuitive as you might expect. People go, “Well, we had a lot of wars going on. Surely it’s combat related. These are combat deaths.” But when you look at these same figures, murder is actually a more common cause of death than combat. And amongst this number, politics was a more common news beat than war correspondence.

Now, why is this? It’s because one good journalist, in the right place at the right time, can change history. One good journalist can move the needle in the context of an election. One well-placed journalist can influence the outcome of a war. This makes them a target. And increasingly, the tools of their trade are being used against them. Our technology is beginning to betray us not just as individuals, but as classes of workers, particularly those who are putting a lot on the line, at risk for the public interest.

Speaking specifically here about journalists, who by virtue of their trade rely upon communication in their daily work. And unfortunately, journalists are beginning to be targeted on the basis of specifically those communications. A single mistake can have a major impact. A single mistake can result in a detention, as was the case in the case of David Miranda, who was passing through London Heathrow, actually, in the reporting that was related to me and my archive material that was passed to journalists. His journalistic materials were seized by the British government. And this was after they intercepted communications regarding his plans to travel through their country.

But it can also result in far far worse than detention. In the Syrian conflict, the Assad regime began shelling the civilian city of Homs to extend that almost all foreign journalists were forced to flee. Now, the government stopped accrediting journalists, and those who were accredited and were reporting their locations were being harassed. They were being beaten. They were being disappeared. So only a handful remained, including a few who actually headed to this city, particularly to the Baba Amr district to document the abuses that were being visit upon the population there.

Now, typically in such circumstances a journalist working in these kind of dangerous conditions wouldn’t file their reports until after they had left the conflict area, because they don’t want to invite any kind of reprisal. It is dangerous. But what happens when you can’t wait? What happens when there are things that a government is sort of arguing aren’t happening and in fact are happening? The Syrian government at the time said of course that they weren’t targeting civilians, civilians were being impacted, these were enemy combatants. And it’s important to understand these lawful abuses of activities happen in many different places. You might be going, “Oh well, this isn’t lawful. Surely this isn’t lawful.” And of course by an international law context you’re absolutely right. By any sort of meaningful interpretation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, this is a human rights violation. It is a ware crime.

But, domestic laws are hell of a thing. And you’ve got to remember that while you might trust American courts, China has courts. Russia has courts. North Korea has courts. Syria has courts. They have lawyers, they have offices of general counsel, who create policies to oversee and regulate these kind activities and create frameworks to justify whatever it is that the institutions of power actually want to do.

Now, in this moment, in that Syrian city of Homs, the government was lying in a way that actually affected international relations. They were saying this was a justified offensive against enemy forces, and yet there was a reporter there by the name of Marie Colvin who infiltrated the city. She actually crawled in I believe through a tunnel, in the dark. Had to climb stone walls and things like that. They couldn’t speak because they were afraid about being fired upon. And she said this was not the case. She actually filed this report live, despite the fact that they were worried that there might be some kind of government reprisal. She spoke four times to four different news agencies on a single day, and they sounded something like this.

I’m at ground zero, and I’m seeing what is being hit. Civilian buildings are being hit. I’m on a street. The houses on this street have been hit, including the one I’m in. They blew off the top floor last week. There are only civilian houses here.

Secondly, the civilians can’t leave. You know, you may say, “Well, if it’s so bad why are you staying there?” The Syrians are not allowing the civilians to leave. Anyone who gets on the street, if they’re not hit by a shell, they’re sniped. There’s snipers all around Baba Amr on the high buildings.

I think the sickening thing is the complete merciless nature of this bombing, whether or not—what is the target they are hitting, civilian buildings absolutely mercilessly and without caring.

[clip of Marie Colvin reporting, at ~49:48–50:42]

Now, this might sound like just another war story. But the next day, the makeshift media center that she was operating from, the one where the building, the top floor had been hit the week before, was repeatedly and precisely shelled by the Syrian army. She died as a result of this shelling, as did a French journalist. The photographer that she was working with was also wounded. And it wasn’t until sometime later that we found, based on Lebanese signals intelligence collection and some other reporting, that the Syrian army had actually given the order to specifically target journalists who were breaking sort of a no news blackout in this organization.

But how did they discover her? How did they know where to aim their shells? Well, according to reporting that occurred just this week, actually, the week prior I believe, her family has filed a lawsuit against the Syrian government. And they have evidence alleging that the radio frequency emissions off her communications that she used to file those news reports were intercepted by the Syrian army. They used direction-finding capabilities to track and locate this illegal, unlawful media center, and then walk artillery fire toward it.

Now, walking artillery fire is sort of how you re-aim artillery when it falls short or when it goes far of where you’re actually trying to hit. You have a spotter somewhere in the city who goes, “Oh, you didn’t quite hit the media center. You hit the hospital next door. Move it a little bit to the right, a little bit to the right.” And they heard these shells coming.

By the time the second shell hit, they knew they were in trouble. This happened at six o’clock in the morning. She was going to grab her shoes, because as is custom in the region you have to enter the house with bare feet, and she was caught by a shell and killed at that point.

Now, there’s a question here among many policy officials, where they go, “Was this legal? What processes do we use to sort of remediate these kind of threats when these things happen? What happens when the policies fail?” And of course this is an argument that the Syrian government itself would say is misunderstood. These were actually attacks that were occurring by terrorists, or whatever. Or we if did these operations they were lawful.

But there’s a larger question of does it matter? Does it matter whether it was authorized by law, or not? Was this a moral action, regardless of whether it was lawful or unlawful? And, are these kind of things preventable? Can we enforce some stronger guarantee of the kind of locational indicators of our activities that we’re putting out there? Perhaps in the case of Marie Colvin, we could not.

But what about the case of future journalists? What about a journalist who has to meet with a source in a denied area, and they don’t want their phone to be shouting into the air, to be giving up some kind of locational indicator of their movement? This is an area that is the focus of our research. Can we detect if the phone starts breaking the rules, and for example if you turn off your your WiFi indicating, you put your phone in airplane mode, you try to turn off GPS. You get a little icon that lights up and says “I’m off.” But is that actually the case? Can you trust the device? What if the device has been hacked? What if something else is going on?

So we wanted to investigate, can we use these same devices that are so frequently used against us as a kind of canary to detect these new targeted attempts for monitoring communications, not just based on the emanations that go out on our own phones, but malware attacks, intentional efforts to compromise the phone. For example, there was an Argentinian prosecutor who, after he was murdered, when he was investigating whether the state had been engaged in serious violations of law, they recovered a malware sample from his phone. Now, that malware sample did not match the operating system of his phone, so it was not responsible in that case. But it was clear that an attempt had been made to compromise his devices and use them against him. This same malware was found targeting other activists, other journalists, other lawyers in the Latin American region.

If we can start to use devices, again as a kind of canary, to identify when these phones have been compromised, and we’re able to get these to a targeted class of individuals such as journalists, such as human rights workers, they can detect that these phones are breaking the rules, they’re acting in unexpected ways, what we can do is we can begin affecting the risk calculation of the offensive actors in these cases. The NSA, for example, is very nervous about getting caught red-handed. They don’t want to risk the political impact of being seen targeting groups like journalists, like American lawyers, despite the fact that they have been engaged in such operations. In rare cases. It’s not their meat and potatoes, but it does happen.

Other governments are not so careful. But, if we can create a track record of compromise, if we can create a track record of unlawful or unethical activity, we can begin creating a framework to overturn the culture of impunity that affects so many of these lost journalists’ lives. In those thousand and seventy cases of dead journalists, or the disappeared, impunity was the most common outcome.

But I want to make it clear here that the idea is not just to protect an individual journalist’s phone, which is a worthy cause, but to again increase the cost of engaging in these kinds of activities, engage in the cost of carrying out lawful abuses of digital surveillance. And without sort of belaboring the point here, let’s go to the actual technical side of this and talk about what we’ve actually done. Bunnie, let’s talk about initial results.

Bunnie Huang: Sure. Thanks for setting all that up, Ed, and motivating the background for why we’re trying to do what we’re trying to do.

When we started out the project, the basic challenge that was outlined is how do we take a venue where reporters meet with sources, and secure it against state-level adversaries? There’s a lot of people who are smarter than me who are working extremely hard to turn your smartphones into mini cyber fortresses.

The problem is that phones are a very large, complicated attack surface. You have email, you have web, you have messaging, you have the ability to install apps. Trying to secure this against a state-level adversary’s very challenging, just like trying to create a city that’s robust against land, sea, and air attack.

But turn over the phone, and look on the back side. This is a surface that’s much simpler, and something that I feel more comfortable with as a hardware guy. And there’s only two really notable features on the back, the antennae. Those form sort of a choke point that we can look at to see if anything’s going in or out of the device. And so if you want to go ahead and make sure that your phone isn’t sending signals, you say, “Well, why don’t we just go ahead and put it in airplane mode.” Turns out the question is can you trust the gatekeeper? Can you trust the UI?

If you go to the Apple web site and you read the little thing about airplane mode, it actually says that since iOS 8.2, airplane mode does not turn off GPS. In fact, when you have your device in airplane mode, the GPS is constantly on and can be pinged without any indication on the UI at all. And that’s a policy that they have for the phones. You can also turn on WiFi and Bluetooth in airplane mode accidentally, or intentionally. And that little icon is still there making you think that your device shouldn’t be receiving or transmitting radio signals.

So the question is is there a way we can independently monitor that gate? Can we install, effectively, a closed-circuit TV camera of our own design, of our own construction, and in our own installation, to audit and verify that this is actually happening?

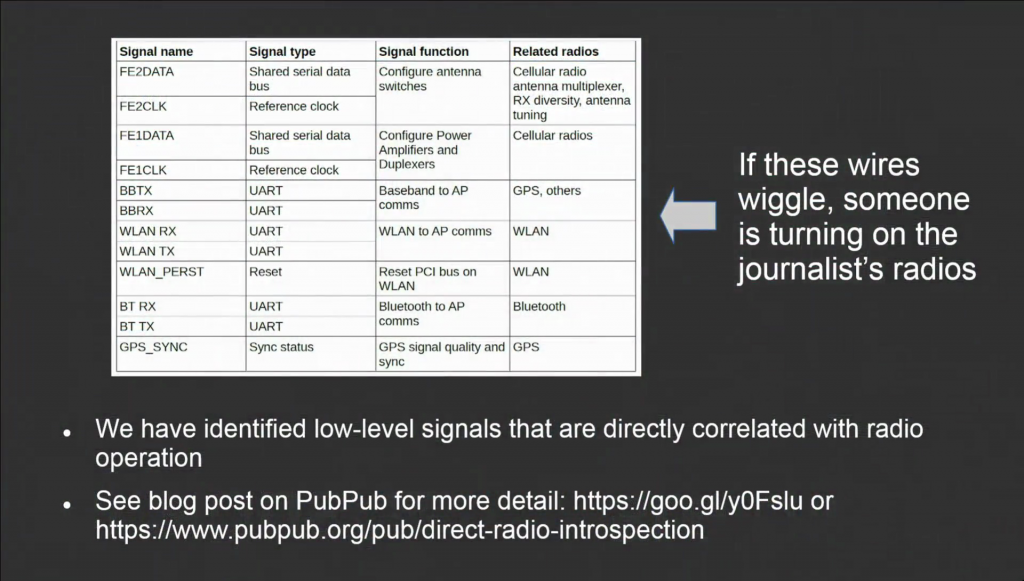

So the technical goal here is to make sure the radios are really off. We want to look at the cellular modem, WiFi, Bluetooth, GPS, and NFC (Apple Pay). It’s a technique that we call “direct introspection.” And we have a set of eight principles that we came up with for this project that we use to evaluate different approaches.

First is that we want to make sure that whatever we come up with is completely open source and inspectable. You don’t have to trust us or what we say.

Second is we want to create a partitioned execution environment for the introspection engine. You can think of the thing we’re doing as like a designated driver for the phone. The phone may be given a spiked drink and unable to assess its own security status. So we have a completely physically-separated execution environment for evaluating the signals.

We also want to make sure that the proper operation is field-verifiable. You need to guard against a hardware failure. So if the cable falls out during introspection, that’s really bad. You want to be able to check that that’s still there. And you also want to guard against potential so-called “evil maid” attacks.

It’s also wanting to make sure that it’s difficult to trigger a false positive. If the thing’s always warning you that your phone is going off and it’s actually not true, you’re going to start ignoring the warnings. And this criterion made us rule out a bunch of more passive approaches like sensing the antennas through the RF emanations, because if you happened to walk by a very strong emitter like a WiFi access point or something, your phone would trip and you would [start] ignoring the alarms.

We also wanted to make sure it’s difficult to induce false negatives. It’s quite possible, for example, a system vendor can be compelled to push an update to your phone through a completely secure mechanism. And so even the system vendor can go ahead and put holes in the walls that you thought were once intact.

We also wanted to avoid leaving a signature that’s easy to profile. So, we don’t want to have something where someone says, “Okay, let’s look for people who have introspection engine on their phone and target those guys because they have something to hide.” So we have to create something that’s essentially very strongly correlated at the hardware level with the activation of the radios. These are signals which even a firmware update or some other kind of remote modification to the phone can’t bypass. So, they’re a very strong indicator of radio activity.

We came up with a list of candidates that are here. I’m not going to go through all of them in detail for lack of time, but if you’re interested there’s a blog post live on PubPub now. And I go through the details of what the signals are, why we chose them, and what we plan to do. But the basic idea is if you see these wires wiggle and you think your phone is in airplane mode, there’s a problem. Something is turning on the radios in that mode, and you know your your phone has been compromised.

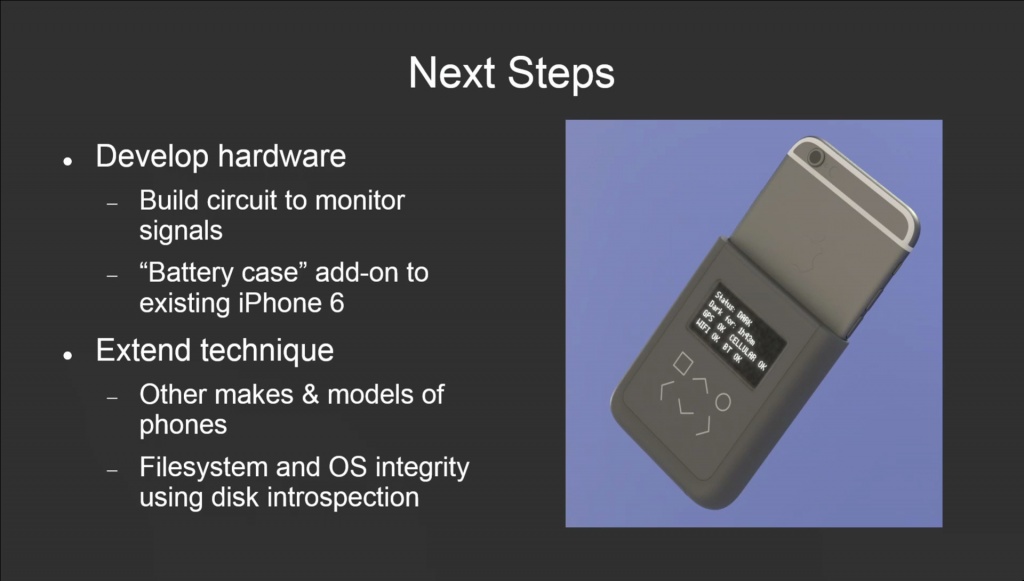

So in terms of next steps, of course we actually need to develop the hardware. We don’t expect journalists to carry around oscilloscopes and hack their phones and so on and so forth. And the basic approach—this is a purely a concept rendering, but the idea is to try to create a battery case-style add-on to the back of a phone which contains the introspection engine. It has its own UI, because you can’t trust the UI in the front of the phone. You have input and output to that device. And there’s a cable that goes between the introspection engine to the phone through the SIM card port on the iPhone 6.

So the solution here is specific to the iPhone 6, but the technique should be extendable to other makes and models of phones. That’s basically it for our presentation. So thanks a bunch, Ed, for setting this up. And I look forward to working on this.

Snowden: My pleasure. It’s been amazing. If I could just say one thing real quick for the room, as this was my first academic collaboration. Having Bunnie as your primary collaborate on the very first time is amazing. He is one of the individuals whose competence gives people impostor syndrome. So I’ll do my best to live up to it. Thank you so much.

Further Reference

Session liveblog by Willow Brugh et al.