Revolutions are messy things, whether they’re either political or technological. The first industrial revolution was powered by coal and steam, but it was also powered by slavery, colonization and child labor, which resulted in centuries of social unrest. The upending of traditional economies and traditional industries created an environmental impact that is still with us today.

One of the ways that industrial revolutions are interesting to think about is that they look differently depending on how and where you see them from. They look different whether you see them from Europe or Asia or Africa. But regardless of time or place, economists and historians generally tend to look at industrial revolutions through the lens of innovation. And in my short talk today I want to encourage a different way of thinking about this.

We can imagine thinking about this as standing very close to a single tree called the Tree of Innovation, if you will. And I want to encourage us to move away from that tree, to step outside the shadow of innovation, and to think about new perspectives that one gets on industrial revolutions by doing this. And I want to talk about three of these things.

Every year at the University of California, I teach an undergraduate class in the history of technology. And at the start of the course I ask my students to complete a sentence. And that sentence is, “Technology is…?” And the responses are fairly predictable. To the average twenty year-old, technology means cars and laptops and smartphones. But hopefully by the end of the semester, my students have gotten a different perspective on this and have come to appreciate that technology is more than just about stuff.

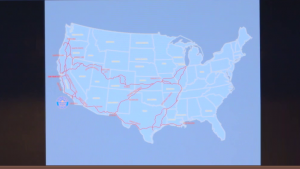

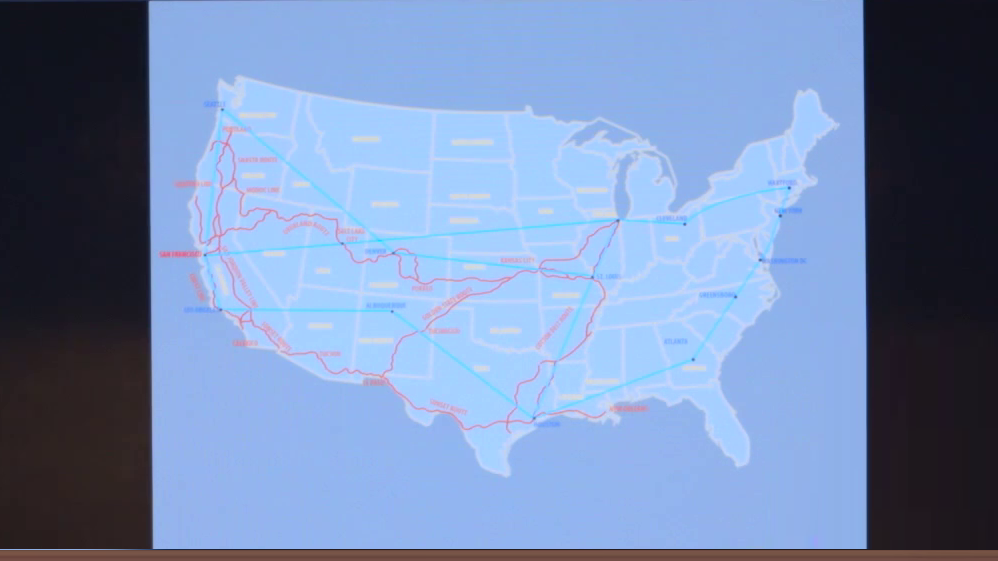

So for example, in the 19th century, engineers and entrepreneurs created complex systems of transportation and communication. But to make something like what’s showing here work properly required that it have order and regularity. And in order to accomplish this, this required adopting scores of technical standards. Technical standards created stability in technological systems, whether it’s screws or shipping containers, standards are what make the novel into the mundane, and they’re what transform the local into the global.

Now, making standards isn’t making things per se, but rather it’s about manufacturing consensus about technologies. What they’re supposed to be, and how they will coordinate and communicate with one another. And if there’s going to be any sort of Fourth Industrial Revolution, then parties will have to adopt similar technical standards to make that work.

Now, industrial revolutions don’t create just standardized parts, they also create standardized people. Here, for example, is an image from around 1920 showing a group of Ford workers, most of them recent immigrants to the United States, having graduated from that company’s school. There they were taught the basis of a new corporate culture, and for many of them they were taught the English language so they could communicate with their coworkers.

This process of making standardized people is something that we can think about as one of the hallmarks of the Industrial Revolution, as well. And this process wasn’t limited to just blue collar workers. Professional credentials and shared research practices fostered the rise of corporate research that was so essential for industrial manufacturing in the United States and Europe throughout the 20th century. And this legacy is still with us now. Think about the numbers that define us. Our school test scores, our credit reports, our actuarial tables. As we go through our lives, our days literally are in so many ways, numbered.

These intangibles, if you will, standards, quantification, and ideology of efficiency, these are part of the foundations of industrial revolutions. And although technology isn’t just things, there is no denying its material basis. And that brings me to my second point.

Over time technologies stack. They layer on top of one another. Their physicality, their material basis, settles on top and forms layers that a geologist might appreciate, and which a historian can reveal and try to understand.

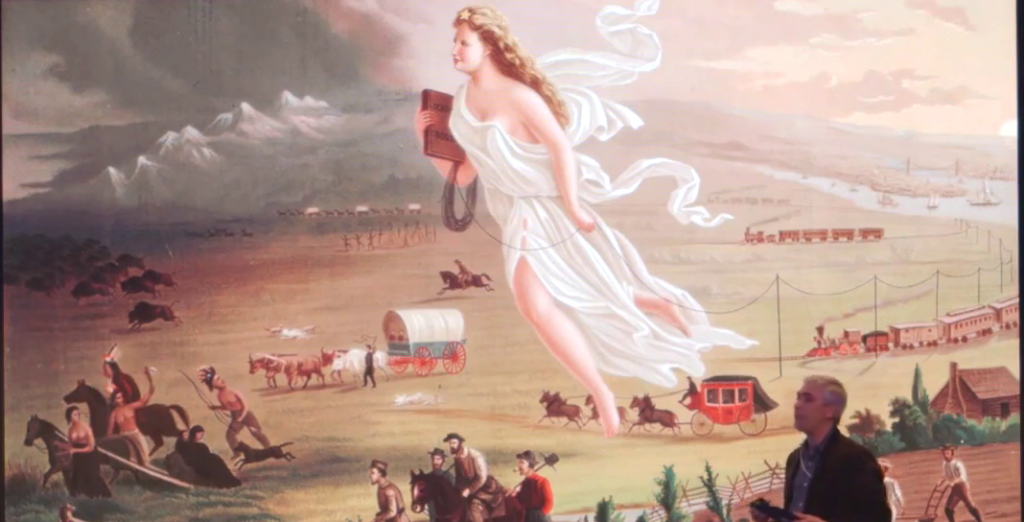

So, consider this picture. It was painted in 1872. It’s called “American Progress.” It’s a not-so-subtle image of the representation of manifest destiny. As Liberty glides forth across the North American continent, settlers follow in her wake, and natives and nature are scattered before her.

But what’s interesting to me is that in her right hand, Liberty holds a telegraph cable that she is unspooling along the pathway of an advancing railway. So again, on one hand it’s a picture of manifest destiny, but in another way we can see this as an image of how interconnected the era’s transportation and communication systems were.

Here’s another way of thinking about it. This is a map of one American railroad company’s map of their railways around 1890. And this is a map of the Internet from about a hundred years later. Should we be surprised that these two layer on top of one another?

Or if we were to put a map of the electrical grid, we would see a very similar pattern. Or if we were to map airmail routes on top of this, we would see a similar pattern.

The point from this is that geography and the environment and the technology all mutually shape one another. Technologies persist through time. But they also coexist with one another in very fascinating sorts of ways.

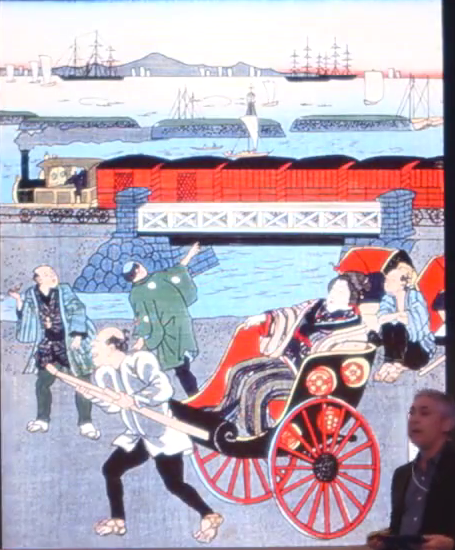

So, this is an image from late 19th century Japan, and what I love about it is it shows a world in which rickshaws and railroads and steam and sail all coexisted with one another. So we can think about industrial revolutions as being distributed unequally in time and space. The technological world isn’t flat. And we are still living in this lumpy and bumpy world as old and new technologies coexist with one another in time.

And what results from this is if we focus too much on the new, the novel, the innovative, we lose track of some of the older technologies that were in some ways more important and more foundational. So, it’s common to hear about how the 19th century telegraph system was like today’s Internet. Except that this isn’t true. Sending a telegram in 1900 was very expensive. It was a one percenter technology, we might say. Not many people could afford to do it. What was revolutionary for the bulk of people who wanted to transmit information was the availability of cheap postage. Systems of transoceanic and transcontinental postage systems allowed for the rapid flow of information and correspondence. But in the shadow of novelty, things like cheap postage get lost in the shadow of the telegraph, if you will.

Speaking of hidden histories, recently Walter Isaacson wrote a best-selling book called The Innovators. It’s a compelling story about how a group of geeky genius entrepreneurs and engineers formed collaborations and helped create the modern digital era. But a difficulty with the book is that it misses the point of what most engineers and scientists actually do. Most of them aren’t engaged in disrupting existing system. Most engineers and scientists spend their careers maintaining systems, maintaining continuity, keeping them functioning.

So. Imagine a book, a hypothetical book. It’s called The Maintainers. What will we see in this hypothetical book? We would see a group of different actors. We wouldn’t see the same people who invented the Web, for example. But we’d see the people who kept that system functioning. It would shift our gaze from Manchester and Silicon Valley and Detroit to wider global infrastructure.

It would be a story more about continuity rather than change. In it, we would see activities like the reuse, the recycling, the repair, sometimes even the rejection of technology. And in the process, people who had previously been on the margins would come into focus in this new and I think quite important story.

People like these folks. This is a farm couple in Kansas during the Dust Bowl era around 1930. What have they done? They’ve taken their automobile and they’ve connected it to their washing machine. We don’t really know much about these people, but I would make the case that they were inventive and innovative in their own particular ways. And it’s by focusing our histories on folks like these as well as the famous and the powerful that will create a rich tapestry of understanding industrial revolutions. We can think about people like these as having hacked the automobile, if you will.

So, moving away from the shadow of innovation gives us a richer history about industrial revolutions. We see how technologies persist over time. We see how technology is more than about just the stuff around us. And we see the important role that maintainers and users have in fostering innovation. We realize then that industrial revolutions and technology itself is more than just about stories of innovation and progress. Technology as well as the social fabric that it is embedded in is itself a work in progress.

Thank you very much.

Further Reference

“A Mountain of Magical Thinking”, a follow-up/summary post about this presentation at Patrick McCray’s blog.