The question that philosophers have asked since antiquity is how should you live? What is the good life for a human being? And the two answers that have repeatedly come back time and time again are that there are two things that matter. One is agency. That’s to say being in control of your life, actively, creatively engaging with the world. And the other is community. That the thing that matters for human beings is relationships. And what I’m going to do is take you on a kind of whistle stop tour of Western philosophy, and look at how these two core ingredients of the good life have fared in the waves of industrial development that we’ve been hearing about this morning. Or to put it another way, will the Fourth Industrial Revolution really bring us the good life?

So, to begin with the question of agency, I going to look at three different ways in which different philosophers have characterized this concept. And I’m going to begin at the beginning with Plato. So, Plato said that in order to flourish you had to be in control. That’s to say you had to be master of your desires. To be ruled by your desires was to be a slave to them. It was as if you were to be ruled by a hydra. That’s to say when you kill off one snake, or desire (for boots in my case), another two immediately spring up in their place. You might think about jets. I don’t know. I like the shoes.

Another way of thinking about agency was provided by John Locke, who said that in order to succeed, in life in order to successfully engage with the world, you have to understand that world. So, for example, if you’re driving a car it’s a very good thing to be able to know how to fix the engine, which my grandfather for example used to do. I certainly can’t, Or, of course there are some countries in the world which don’t allow people to drive, don’t allow women to drive. That’s another example where it’d a very good idea, where understanding liberates us and gives us agency in the world.

And finally, the third philosopher whose idea of agency I want to look at is your friend Karl Marx, who said of course that in order to lead a fulfilling life what you need is you need to act in the world. You need to create. You need to produce. You need to labor. But you have to have a sense of ownership over that labor. You have to identify with the work that you do. And we can I’m sure all relate to this when we think about writing, or painting, or climbing a mountain, or skiing down it. There’s very little in life that’s good that doesn’t come at some kind of cost of activity or creation. Activity, agency, is what counts.

And arguably, these things are threatened by the industrial revolutions that we’ve been hearing about, and in particular in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Of course Marx himself gave the most piercing analysis of what happens when one is alienated from one’s labor. The more you become part of a production line, the more repetitive, the more discreet, the more mindless your tasks, the less a human you are. The more of a kind of shell of a human, of a shadow of a human. The more you become like an instrument, or an object, until humanity is erased altogether.

That’s the production side. On the consumer side, it looks like the Fourth Industrial Revolution should give us a utopia. A world where all our needs are met. A world where we’re completely plugged in to everything that we might possibly desire. But of course the danger here is the passivity, the opposite of the activity that our philosophers told us was crucial to the good life. But everything is given to us. We don’t have to do anything anymore.

A further thought is that we lose understanding, we’re deskilled. Not only [can we not] fix our car, we can’t remember our phone numbers. Which of course is very complicated when your battery runs out on your phone and you’re on the top of a mountain. And also, there’s a danger with smart marketing and acceleration of consumerism that comes with that. That there are things we didn’t even know that we wanted until they’re beamed into our phone. And then suddenly we become victim again to Plato’s hydra, unable to battle off these desires that are continually put in front of us.

So that’s agency, which we out to keep an eye on. The second thing that philosophers have said is crucial to the flourishing life of a human being is community. Again, going right back to the beginning, here’s Aristotle. Aristotle said, as I’m sure you all know, that man is by nature a political animal, a zoon politikon. That’s to say a man who flourishes when he is in a community. And Aristotle said that community is only possible when you have ethics. That’s to say when you can deal justly with other human beings, when you recognize their humanity.

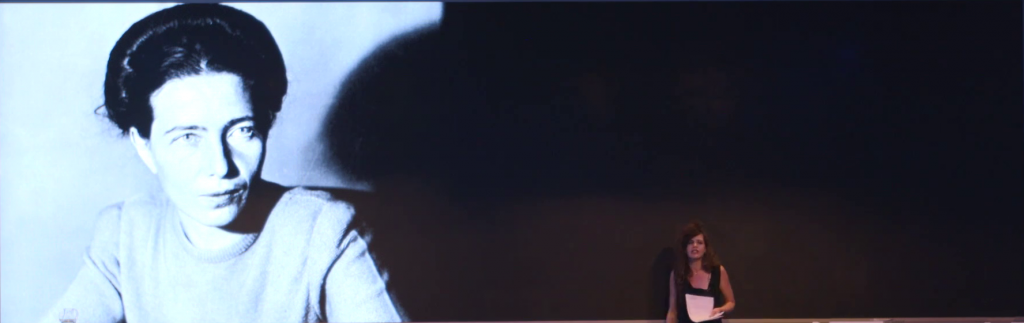

Simone de Beauvoir…I’m moving forward to the 20th century. She brought together the ideas of agency and of ethics when she said in her existentialist way that you are nothing as a human being unless you act. And moreover it’s not good enough just to act in any passionate way that you want. What you have to do is you have a responsibility as a human being to act ethically, to care for your fellow human beings. And of course in her mind was appeasement in the 1930s, and the impetus as she saw it on France and Britain to act.

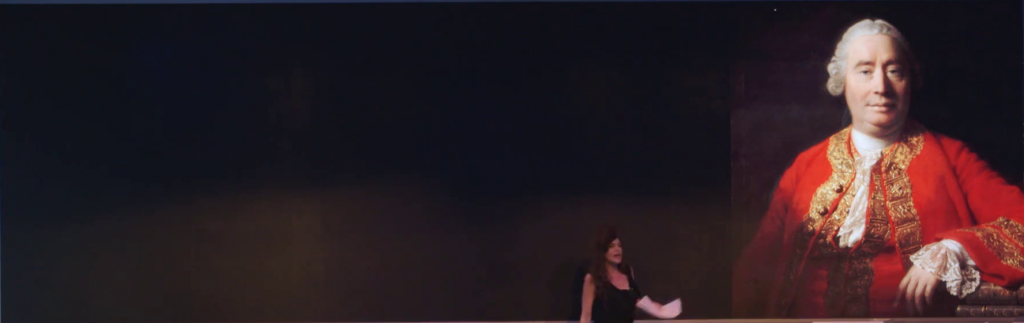

Now, how do we get community? How do we get ethics? Well, another way putting that is, how do you learn to care about your fellow human beings? The Scottish enlightenment philosopher David Hume, he said that the only way that you learn to care is by having empathy. And you don’t get empathy just by understanding facts and figures. Only if you look in the face of human suffering, and of human joy, and of human dignity, do you start to kickstart those ethical impulses upon which community depends.

And of course there’s a danger in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution that rather than increasing empathy, it’s going to pull us further apart. There are various motors of atomization that we have to be aware of. The first one, doubtless obvious to us all, is that in our increasingly virtual communication, we have less and less physical contact with each other, less and less actual contact with each other.

We live in increasingly siloed worlds. We have our personalized news feeds. The echo chamber of Twitter, where we’ve become less and less aware of what other people think, what other people’s values are. We have the massive problem of growing inequality which comes about in part as a result of the high-tech, high-touch, new economy that seems to be only accelerating in the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

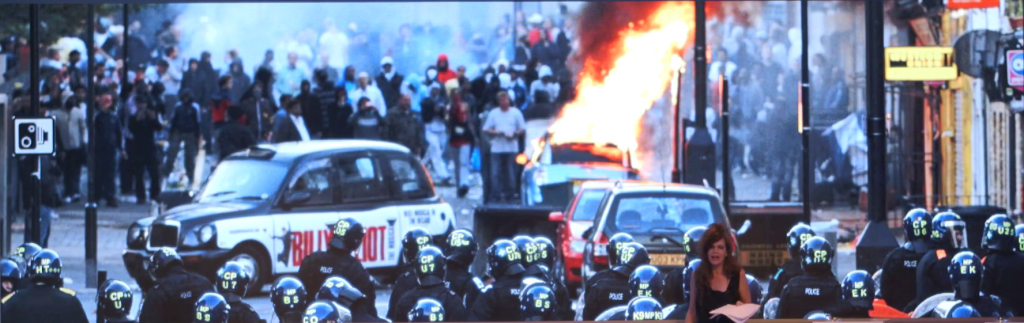

Now, you might think this sounds a bit apocalyptic and depressing, and so I want to end with an example, a concrete example, of where I live. This is two streets from where I live in Hackney, in London. This shows the riots that broke out in London in 2011 when a young black man, Mark Duggan, was shot dead by the police. And it sparked off looting and burning. And it seemed at the time—I myself remember trying to cycle my daughter through these riots and thinking, “Oh God! This is…this speaks to a sort of terrible dislocation. A terrible inequality.”

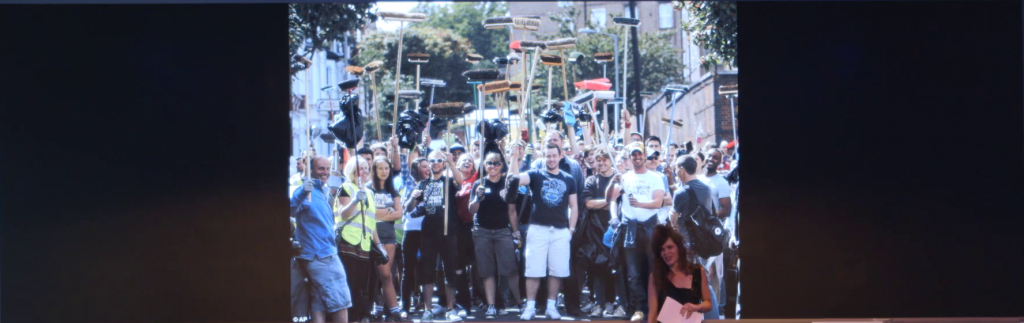

But do you know what happened the next morning? It might look like a protest, but do you know what this is? This is the community spontaneously coming out, en masse, and cleaning up the streets. There were more people coming out to clean up than there were to riot the day before.

And so the question that I want to leave you with is, what kind of a world do you want to live in? Do you want to live in an atomized world with walls high, both virtual and real, or do you want to live in a community? Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Hanna Dawson faculty profile, King’s College London