Jenny Toomey: We’re bringing up Brendan Nyhan, who is coming to us all the way from Dartmouth College. Brendan in his past ran with some colleagues of his a terrific watchdog political spin called Spinsanity between 2001 and 2004, which was syndicated in Salon. And he has a bestseller, All the President’s Spin. Back in 2004 one of the ten best political books of the year. Recently he put out a report called “Countering Misinformation: Tips for Journalists” which I suspect may have something to do with what he’s about to talk about. Thank you.

Brendan Nyhan: That’s right. Thank you very much. So in my past life I was a fact-checker. So if you remember the commercial from the Hair Club for Men, “I’m not only the president, I’m also a client,” well, I’m not only an academic, I used to do this. So I’ve experienced first-hand the challenges of trying to correct misinformation, and in part my academic research builds on that experience and tries understand why it was that so much of what we did at Spinsanity antagonized even those people who were interested enough to go to a fact-checking web site. So it was a very select group of people.

And at first it’s a very puzzling phenomenon that we antagonized half of our readers every day. And I know the other fact-checkers in the room will understand that situation. But if you think about motivated reasoning from the perspective Chris has described, it’s precisely those people who are best able to defend their pre-existing views and who have strong views who are most likely to go to a site like that in the first place. And that’s what made it so difficult.

So, I’m very proud of the work that we did at Spinsanity. This was a non-partisan fact-checker that we ran from 2001 to 2004, sort of a precursor to factcheck.org and PolitiFact—more sort of institutionalized fact-checkers. This was two friends and me doing this in our spare time. And we eventually wrote a book and then decided that the model was unsustainable and we shut it down.

But it was a fantastic experience, and what it made me think about was why it’s so difficult to get people to change their minds. And I think Chris has done a great job laying out all the reasons that people don’t want to be told that they’re wrong. And let me just add to that that it’s very threatening to be told that you’re wrong. There’s a cognitive element to this and a political element to this, but there’s also a self-image or self-concept aspect to this that my coauthor Jason Reifler and I have explored in our research. But I just want to underscore how threatening it can be to be told that you’re wrong about something. And that the defensive reactions that threat can generate are part of what make correcting misperception so difficult.

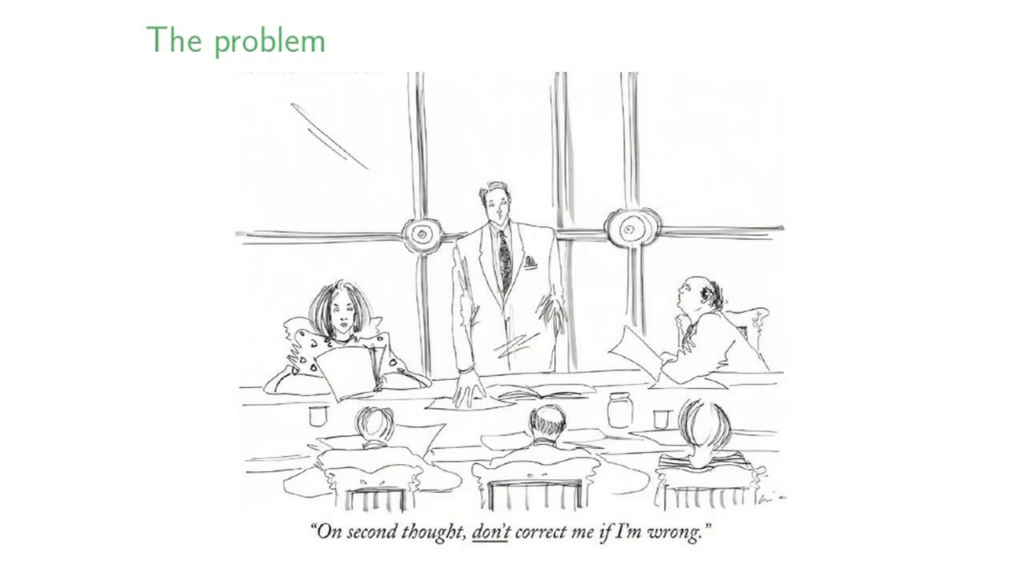

So what I want to do is think about what are different approaches to trying to correct misperception. And the obvious place to start and a place that I have myself called for in my writing is for the media to be more aggressive in trying to fact-check misperceptions. This is a conference about truthiness in online media, but the mainstream media is still a very potent source of information, very important in the political culture of this country. So what if the media were more aggressive in trying to counter misinformation?

False ‘Death Panel’ Rumor Has Some Familiar Roots, Jim Rutenberg and Jackie Calmes, The New York Times, August 13, 2009

This is an example, the death panel story in 2009. The press was more aggressive in fact-checking that claim than say, they were in the run-up to the Iraq War. So, is that likely to be effective? And what my coauthor and I did was we actually looked at this experimentally. We took undergraduates and we gave them mock news articles where we could experimentally manipulate whether or not they saw the corrective information. So we have precise control of what they’re seeing and we can measure exactly what their reaction is to it. And the question is what happens when we give them this corrective information. Is this effective at getting them to change their minds about the given factual belief.

And the answer is generally no. So, the pattern across the studies we’ve conducted is that there’s frequently a resistance to corrections on the part of the group that’s most likely to want to disbelieve that correction. This is something we call disconfirmation bias, and it’s very consistent with the story that that Chris described to you a moment ago.

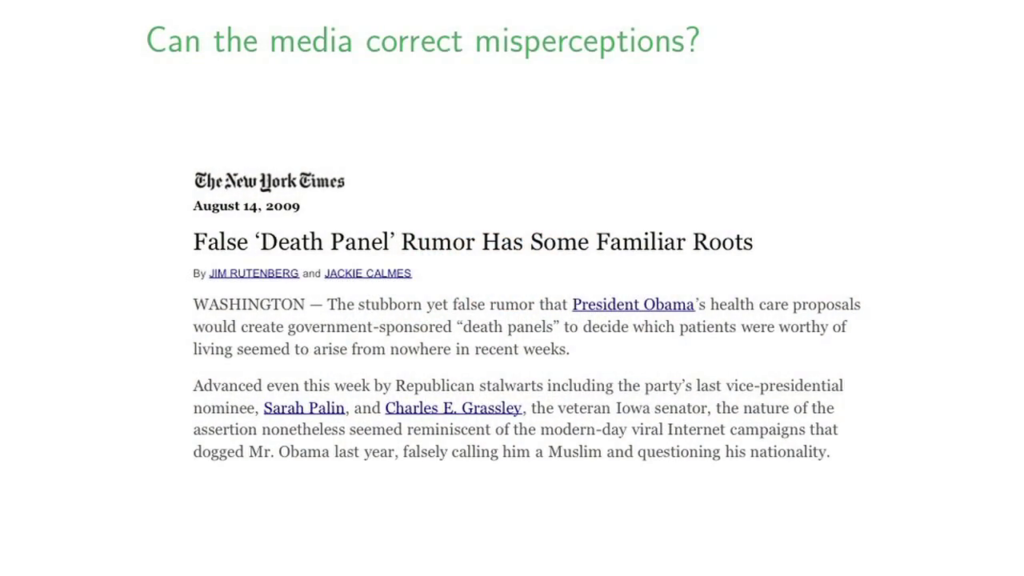

This is a claim was made by John Kerry and John Edwards in 2004. They made statements suggesting that President Bush had banned all stem cell research in this country. That’s not true. He limited federal funding to preexisting stem cell lines. But the language that was used implied that there was a complete ban on stem cell research.

So we exposed subjects to a mock news article about this claim, gave them a correction. Well, who’s likely to want to believe this claim? Liberals who don’t like President Bush. And what you’ll see is that our correction was not effective at reducing their reported levels of misperceptions. Conservatives were quite happy to hear that President Bush hadn’t done this and to go along with it. Liberals on the other hand didn’t move. So the correction isn’t working.

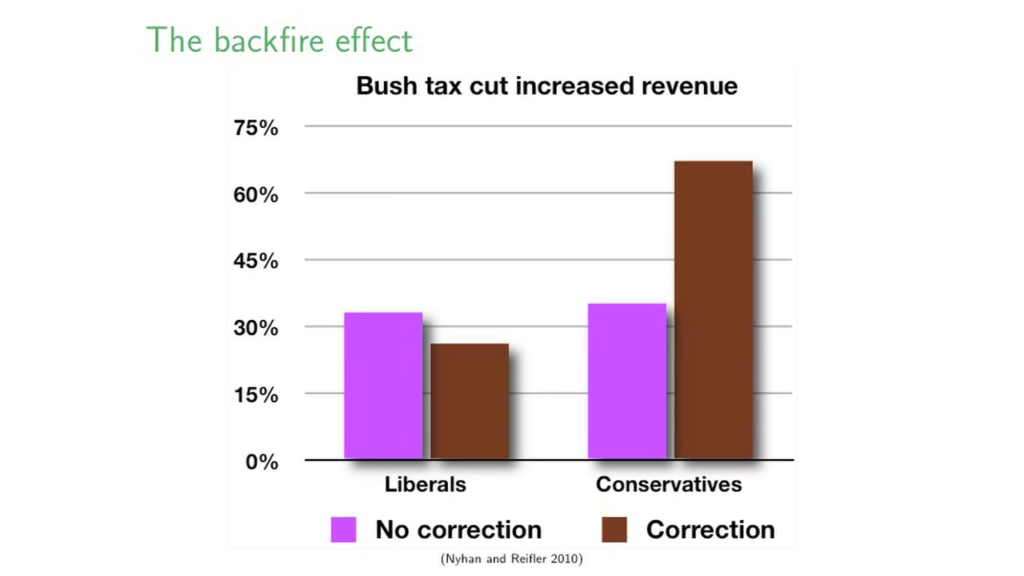

So while that might be troubling enough, it gets worse. In some cases, corrections don’t just fail to change people’s minds, they make the misperceptions worse. And this is what we call the backfire effect. We document two of these in our article, which I’d encourage you to read. Here we’re talking about the claim that President Bush’s tax cuts increase government revenue, a claim that even his own economists disagree with. Virtually no expert support for this claim.

Again, liberals, perfectly happy to go along with a correction of that statement. Conservatives double down, in exactly the way that Chris describes, becoming vastly more likely to say that President Bush’s tax cuts increase revenue rather than less. So in our efforts to combat misinformation, if we’re not careful we can actually make the problem worse. And this is something that everyone should think about in this room when they’re thinking about how to address misinformation. The Hippocratic Oath of misinformation. Try not to do harm. Because you can.

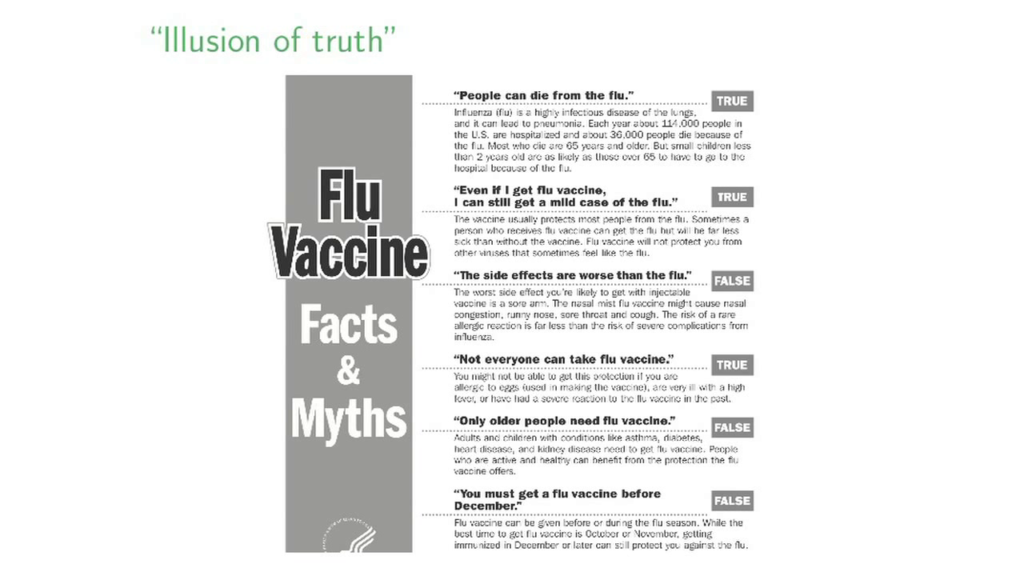

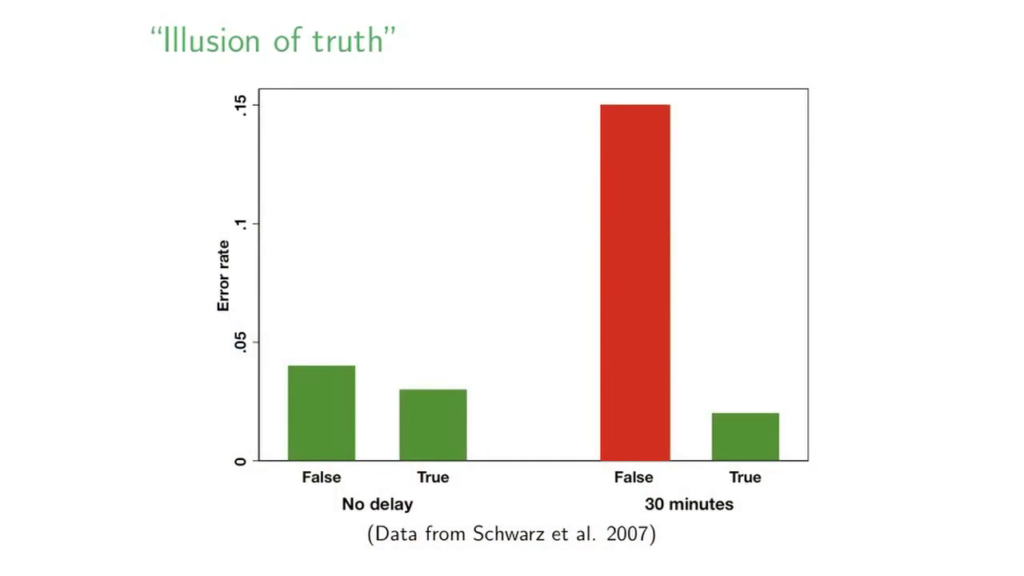

Let me just add another point here. There are also people out there who mean well and are not motivated reasoners in the way way that Chris and I have discussed. And correcting misperceptions can still make them more misinformed, too. And one mechanism for this is what’s called an illusion of truth effect. So this is from a CDC flier of facts and myths about the flu. This is not something that people have strong preexisting beliefs about in the same sense as their politics, right. Most people are not epidemiologists and experts in the characteristics of the flu. So we tell them some things and we say, “These ones are true and these ones are false and here’s why.”

But when some psychologists showed people this and then divided the ones who saw this— Now, some of them only got the true statements, some got the true and the false. And then they looked at how well they retained this information. What they did was they divided those folks and gave a thirty-minute delay for some people. And after just thirty minutes, a significant percentage of people start to misremember the false statements as true. This is a well-documented phenomenon in psychology where familiar claims start to seem true over time. So again, in trying to correct the misperception, you’ve made the claim more familiar, and that familiarity makes people more likely to misreport these statements as true.

So again, these are folks who have no particular dog in this fight. So again we have to be very cautious about the steps we take. And again let me just underscore that the reason we can tell that these effects are happening is because we’re testing them experimentally. That gives us full control and ability to disentangle exactly what’s going on, which is very very difficult otherwise.

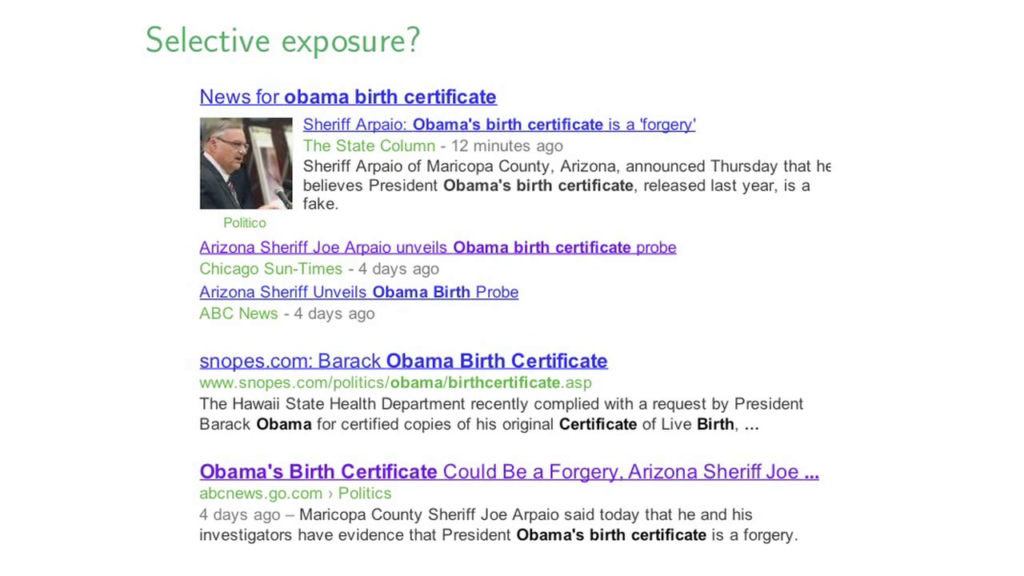

A final note about correcting the problem. The other thing I would just say is while we can talk about fantastic tools we could develop to help correct misinformation, the problem we have is that the folks who seek those tools out may be those whom we’re least interested in reaching, because they may already believe what we want them to believe in any particular case. And even for them when we do challenge them, counterattitudinal information is only a click away.

This is a snapshot of the results I got when I typed “Obama birth certificate” into Google this morning. Let’s say I want to believe Obama’s birth certificate is real. Well, I can click on the Snopes debunking, but it’s surrounded by a headline that says it could be a forgery. And news about Sheriff Joe Arpaio’s press conference. So, choose your own adventure. Which one do you want? It’s very easy to seek out supporting information for whatever point of view you want to defend. So when we do challenge people, the technology that we have makes it easier and easier to reach out and buttress that view that’s been challenged. So again this is a very difficult challenge. It’s much easier to buttress those view now than ever before.

Now that I’ve depressed you, let me talk about things we can do that are perhaps better approaches. And let me just say that these are part of a New America Foundation report [summary] that my coauthor Jason Reifler and I wrote with help of several people in this room—it’s available on the table out there. And there’s a couple of other reports that are part of that package about the fact-checking movement. But these are series of recommendations that we’ve developed based on available research in psychology and political science and communication, on how you can communicate in a more effective manner that’s less likely to reinforce misperception.

Joe Arpaio on Obama’s birth certificate: It may be fake, Tim Mak, Politico, March 02, 2012

The first thing. This is what not to do, okay. Remember I told you about that illusion of truth effect where seeing the false claim and it becoming familiar to you makes you more likely to misremember it as true. This Politico article in its sixth or seventh paragraph eventually gets around to saying “actually, there’s extremely strong evidence that Obama’s a citizen and this is all nonsense.” But if you look at the top of the article, which is what’s excerpted here, what it’s done is it’s restated that claim both in the headline and the lead statement. And by restating these claims again and making them more and more familiar, we’re actually likely to create this fluency that causes people to misremember these statements as true. So when I say best practices here, this is what not to do. And I have an article on the Columbia Journalism Review blog about this if you’re interested in reading more about this problem.

Another problem, negations. Again, there are well-intentioned people who are confused sometimes. We’ve often been talking about motivated reasoning and people who don’t want to be convinced. But even those people who are open-minded can have a tough time with negations. When we try to say something is not true, we may end up reinforcing that claim we’re trying to invalidate.

So this is an example of some well-intentioned folks trying to debunk, to discredit a claim that MMR causes autism. The problem is they have “MMR…cause autism” in the headline. You stare at that long enough and people will start to get nervous. And my coauthors and I have have done an experimental study finding similar effects, that trying to correct the MMR/autism association can actually make people less likely to vaccinate rather more.

A third recommendation. And this is really for the journalists in the room. But the notion of of artificial balance, in which each side has to be equally represented in factual debates, has been shown to mislead people quite a bit. So Jon Krosnick in Stanford and his colleagues have a study showing that providing a balanced report in the sense of one scientist who says global warming will have destructive consequences and one who says it’s great—the planet’s nice and warm, (which is this guy’s message)… Providing that balanced point of view is dramatically changes how people interpret the scientific evidence. And I don’t want to pick on this particular debate, but just to say that reporting needs to reflect the balance of the evidence. And the he said–she said perspective that Kathleen mentioned earlier that leads to this sort of quotation of fringe sources to provide balance can really mislead people. And that’s something to be avoided whenever possible.

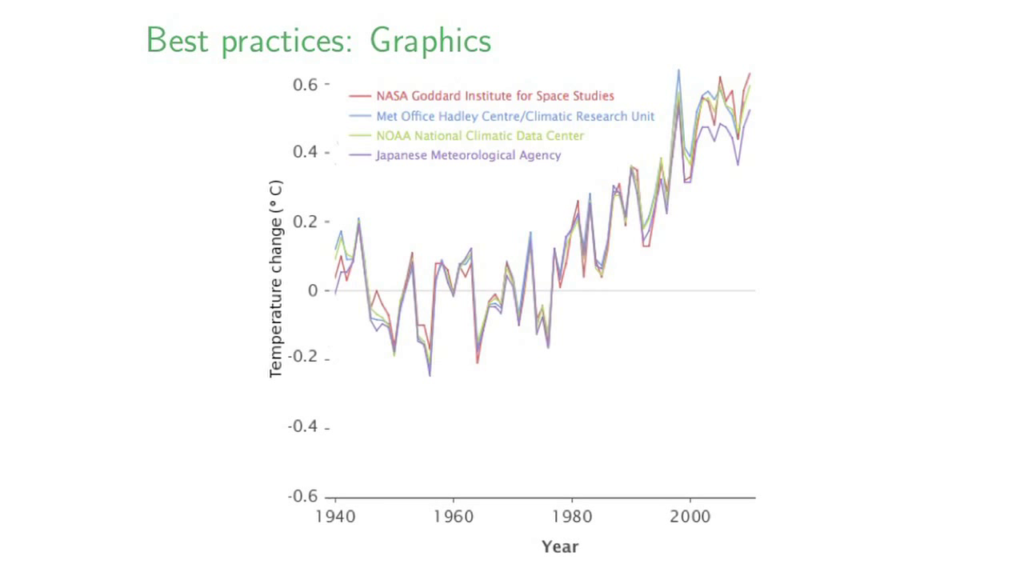

Another recommendation. Graphics. People are really good at arguing against textual information. At least in the experiments we’ve conducted, graphics seem to be more effective for those quantities that are… Let me say that a different way. For misperceptions that can be graphed, right. There’s lots of misperceptions we can’t graph. I don’t have a graph of Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. I can’t put one up for you. But what I can do is show you that four different independent sets of temperature data show dramatically increasing global temperatures and are extremely highly-correlated. This is from a NASA press release. We found this was quite effective, much more effective than equivalent textual correction, at changing people’s beliefs about global warming.

Experts Debunk Health Care Reform Bill’s ‘Death Panel’ Rule, Kate Snow, John Gever, Dan Childs, ABC News, August 11, 2009

Another approach, and this is something I don’t think we have talked much about so far. But it’s important think about credible sources to people who don’t want to be convinced. This is an example of what I thought was an exemplary report on the death panel controversy from ABC news that said— It’s framed as experts, right, “doctors agree that death panels aren’t true. So it’s going to medical expertise, it’s getting out of the political domain, and it’s saying that even experts who do not support the version of the healthcare reform bill being proposed by President Obama agree that death panels aren’t in the bill. And it goes on to quote a Republican economist with impeccable credentials on that side of the aisle saying there’s lots to oppose about this bill but death panels isn’t one of them. And to the extent that we can reach out and find those more credible sources to people who aren’t willing to listen to the normal people who are typically offered to them, that may be an especially effective approach.

So for more I’d commend to you the report that I mentioned earlier as well as those by my colleagues about the fact-checking movement. Thanks very much.

Further Reference

The Rise of Political Fact-checking

The Fact-checking Universe in 2012

Truthiness in Digital Media event site