Scott Sullivan: Okay, so this work started for me back in 2017 when I read the article The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells. Has anybody read this? Shortly after he came out with a book of the same title. Reading this book has been described as an act of emotional violence. So if you’re into not sleeping at night, I highly recommend it.

So basically the author, he read a lot of studies, and he’s a journalist, and he basically found out that the media was drastically under-reporting the severity and speed of the climate crisis. So he wrote this book, and and really one of the big takeaways for me was that the climate is going to be the dominant lens of society going forward, right. It’s going to affect big, large-scale geopolitical decisions kind of all the way down to the personal level. To where we work, what we eat, where we live.

So basically, I read this book, I read a bunch of other books. I’m shitting my pants. And I have to figure out what to do. I have to figure out something to do. A lot of people are motivated by more positive things, and utopian kind of things. I am apparently motivated by terror. It works.

So I started off kinda weird. I started making weird videos for my then-unborn daughter. Making videos of grocery stores because I think that grocery stores are going to look very different and I wanted to show or what they used to be like before she was born. As was previously mentioned, I started growing a couple hundred trees and threw up solar panels on the top of my house. And just kind of scattering things around and trying to figure out what to do.

And you know, ultimately I kinda had some of my local bases covered. Like immediate community. I started flooding all my friends with trees for them to plant. But I needed to figure out what I could do as a designer in the future. Like as a human-centered designer what is my role, what is our role, in this kind of bigger picture? If this is the dominant lens of society, what’s our contribution?

So looking around, a lot of the designer things that are around the climate or you know, ecological things, are all plastic-based. And that makes sense. Plastic is kinda easy to wrap your head around. You cut open a bird, it’s full of plastic, and then you look down at your hand, and it also has plastic, and it’s easy to kind of make that 1:1 connection with like the kind of cause and effect of that behavior.

But ultimately I kinda see this stuff as you know, not all that useful to the big picture which is this, right:

So this is our big target variable. 411.85, the number of parts per million of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere. And this is much more difficult to really wrap your head around. I mean there’s not even units, right. It’s just a ratio. It’s .00004 of our atmosphere and somehow that gives us the terror in Australia and you know, half of Bangladesh flooded out. A million refugees out of Syria. And California on fire, Venice flooded.

And that’s at 1.1 degrees. So, this is a bigger problem, right. Figuring out what to do and figuring out how to kind of like, explain this to me and everyone else in a reasonable way.

So Dan Ariely, a behavioral economist, he describes the climate crisis as basically the perfect storm of human apathy, for three big reasons. So one is that it’s generally seen as long-term and in the future, at least when he made this statement it was seen as more long-term and in the future. Generally when we don’t see things happening as a direct effect of what we’re doing, it’s harder to care. But the biggest thing is that anything we do is going to be more or less a drop in the bucket for this specific cause. So there’s nothing that I as an individual or you as an individual are ever going to do where you are going to see the material output of that reflected in the world. It’s not gonna happen. This is a massive, huge, collective problem.

So. Once again, as designers how do we tackle this? We look around, and most of the solutions in this space are large-scale. They’re engineering things. This is an amazing project. This is CarbFix by Reykjavik Energy. We see a lot of kind of renewable energy kind of things; smart grid. Cool agricultural projects. These are kinda big, and they’re very engineering-focused. And ultimately, we look at the size of the problem. The speed of this work is going to be too little too late to scale by the time we need to scale it up.

So luckily, the other 80% of the solution is something we can affect. And basically what needs to happen is a massive reduction of consumption, and that’s going to require behavioral change. So that’s kind of where I landed in terms of how design is going to contribute to this.

And that is austerity as a service. So, basically in my work in the past as a humans-centered designer, behavioral change is pretty much the most meaningful work that I have done. So, I did a lot of work in the wearables industry. So helping to enable people to meet their own personal goals in terms of health. Did a lot of work with Capital One in behavior change, helping people work towards their financial goals.

So, I’m going to walk through this idea of what this might look like. And I’m going to use a lot of examples around reduction of home energy but really this applies to anything. Like, personal use in home is kind of one of the more… Energy in the home is a more obvious example of this. But it applies to retail, food, any kind of financial services. There’s going to be some level of reduction and this is going to be reflected across all aspects of our society.

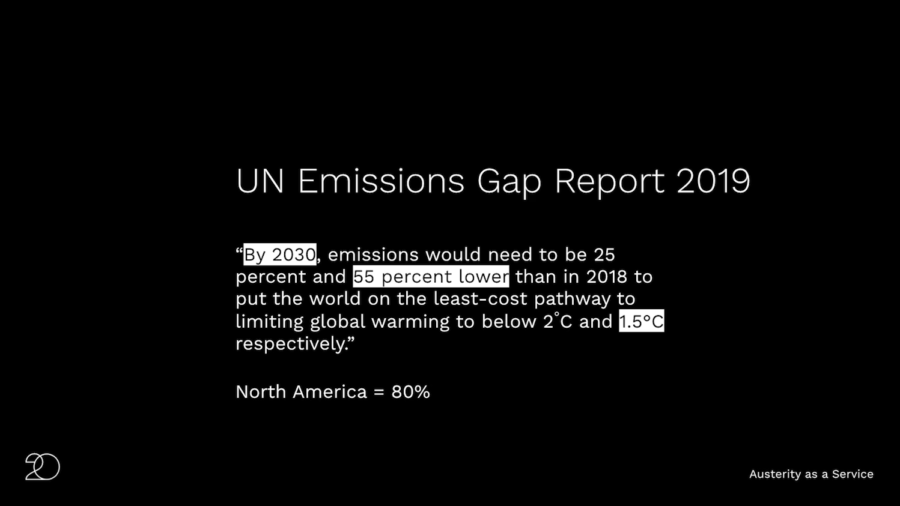

UN Emissions Gap Report 2019

By 2030, emissions would need to be 25 percent and 55 percent lower than in 2018 to put the world on the least-cost pathway to limiting global warming to below 2°C and 1.5°C respectively.

North America = 80%

UN Emissions Gap Report 2019 [presentation slide]

So how much do we need to lose? We talked before about what our targets for 2030—2030’s a big year. Basically, to stay at 1.5 degrees—which is not going to happen. 2 is probably not going to happen but let’s just say this is our goal. We need to get 55% lower. And if we lived in an equitable society, which we should, me—my part of the world, North America needs to lose about 80%. Because it’s 55% across the board and we produce far more than average.

So how do we do that? So let’s say we’ve got ten years to do this. We want to help people reduce 10% every year for X number of years.

Step one is runway. This is really the most important part of this. It’s for multiple reasons, right. So we’re giving them a year, if possible, before formally enforcing kind of any restrictions on consumption. And this is good for a couple reasons. The first of which is that we’re not imposing it on people right away. We’re actually imposing this restriction on a kind of disembodied future self that they can kind of disconnect from and put that off for a little bit, which is good, right. So our chances of acceptance in general are much better in that case.

But more importantly than that, it gives us as designers this onboarding period. It gives us a certain amount of time— And most of the most important work that we’re going to be doing here in this whole like, thread of work, is going to be in this runway. And what that looks like is gonna be a lot of experiential learning.

So, there’s a lot of abstract information, especially with behavior change. So a good example of this is with Fitbit and the first kind of pedometers. If you remember when they came out, the goal was 10,000 steps. And if you would’ve asked me the day before I got my first Fitbit 1, if you would’ve told me, “You take three thousand steps a day,” I would’ve believed you. If you would’ve told me I took fifteen thousand steps a day, I would’ve believe you because I have no idea, right. These are big numbers. I know what five steps looks like and feels like, but I have no idea what ten thousand feels like.

And that was the first big breakthrough of these wearable devices. So, what we did was we were able to kind of contextualize our own behavior so the first day that you got that Fitbit, you just kind of went about your daily life. You’re like okay, so I took 7,000 steps. So you know what 7,000 feels like. You know what your day was like when you took 7,000 steps, and if you want to work towards a goal you’re gonna have to take that day and do a little bit more. You’re going to have to meander on your way to work, take a little walk on your lunch break. Get it up a little bit. And over time…as quickly as a week or two, once you kind of change those habits and change your behavior, right—we’re changing behavior—you don’t even need to measure it anymore because you know what the day is like and you just live that day. The device becomes almost meaningless.

So, that’s what we really need to focus on here. When we’re asking people to make changes in their behavior and habits, we need to first contextualized with their existing behavior.

So generally, there’s this kind of cause/effect cycle. So there’s going to be a period of measured behavior. Then we give them feedback. We allow them to say, “Okay, so here’s this abstract number. You just lived this period of time. And this is what you did during this period of time.” They make an adjustment in behavior. Then we measure that adjusted behavior. And then we give them feedback on that adjustment cycle. So you made this change, and this is the result of that change. And generally you know, in a year we might get three or four good cycles where people can start to build that understanding of the cause and effect relationship between their behavior and the consequences of that behavior in some kind of metric that we choose.

And the third big part is this the intervention and accessible action. So, during that time period when we’re asking them to modify their behavior, we’re going to present them with options. Different alternatives to what they’re doing right now. A lot of it is going to be like—so for the electricity and housing energy consumption, it’s going to be subsidizing high-performance insulation. In the food area it might be building community gardens. Or you know, making out-of-season produce require far more stamps to purchase than in-season produce which might require zero stamps. Kinda stuff like that.

Beyond that, the big thing is these kind of…these interventions, okay. So these generally happen in two different ways and it really depends on the kind of level of fidelity of the data that you have available to you. So, if you’re getting real-time data, you can have threshold-based interventions. And these are by far the most useful, I would say. And what I mean is that you’re consuming X amount of anything… This is something that was really big in banking. So you know, we had real-time information on what people were spending because they were spending it via us, right, Capital One. And we were able to kind of craft these intervention saying, “Hey look, you have this financial goal. You crossed this threshold in spending. So like, you can do whatever you want, but we just want to let you know that you want to buy a house in five years…you’re going to have to tone it back a little bit.” That’s it.

Other than that, if we don’t have that level of information, which is probably going to be likely at least for the housing stuff, it’s going to have to be kind of planned intervals like saying, “Hey. Just a reminder. What’s up. You need to be a little cautious with your use of electricity this month.”

So, this is something that feels weird, I guess, for all of us kind of designing backwards from what we were doing before. And it also…I don’t think is going to be something that we’re going to do with a consumer lens, right. I think this is going to be at a government level. It’s going to be kind of enforced from the top down. There’s us, all of us bleeding hearts in this room that would probably do a lot of this at least some of it voluntarily. But we’re not going to get down 80%. And there’s also the xenophobic 30% of society with “Fuck Greta” bumper stickers that are definitely not going to do it voluntarily. So there needs to be a system in place, like a much higher power who’s actually kind of enforcing these things.

And this is kinda dark, right, this is a dark timeline. It’s not fun. It’s not fun for anybody. But these reductions, it’s very important to kind of keep in mind that this reduction of consumption is going to happen one way or another. So it’s either going to happen when we do it voluntarily and it’s designed and we do it in a way that allows people to have some level of dignity. Or it’s going to happen when the… When there’s a collapse. When the infrastructure that allows us to consume at the level that we’re currently consuming no longer exists. And that’s it. Thank you very much.