Christo Wilson: Hi! Good evening. So I’m Christo Wilson. I’m a computer science professor over at Northeastern. And like Karrie I consider myself to be an algorithm auditor. So what does that mean? Well, I’m inherently a suspicious person. When I start interacting with a new service, or a new app, and it appears to be doing something dynamic, I immediately begin to question what is going on inside the black box, right? What is powering these dynamics? And ultimately what is the impact of this? Is it changing people’s perceptions? Is information being hidden? What is going on here?

So to give you a little flavor for how this work plays out, I want to talk about one of my favorite audits that we conducted, where we looked at surge pricing on Uber. Now of course, Uber is a good, upstanding corporate citizen, right. There’s no reason to suspect that they might be tinkering with the prices just to charge you more money. But nonetheless, we were curious how these prices got calculated. So we signed up for dozens of Uber accounts. We spoofed their GPS coordinates, to place them in a grid throughout a metropolitan area. And that enabled us to see all the cars that were driving around that were available. When those cars disappeared, that implied that they got booked and we could see all the prevailing prices.

So, the good thing that we found from this is that indeed, what we saw was that the surge prices strongly correlated with supply and demand for vehicles. And that matches our expectations for how we think these numbers should be calculated. So that’s good.

The bad thing was that we also found that Uber was randomly giving users incorrect prices for about seven months. And they didn’t realize that until we got in touch with them and talked to their engineers.

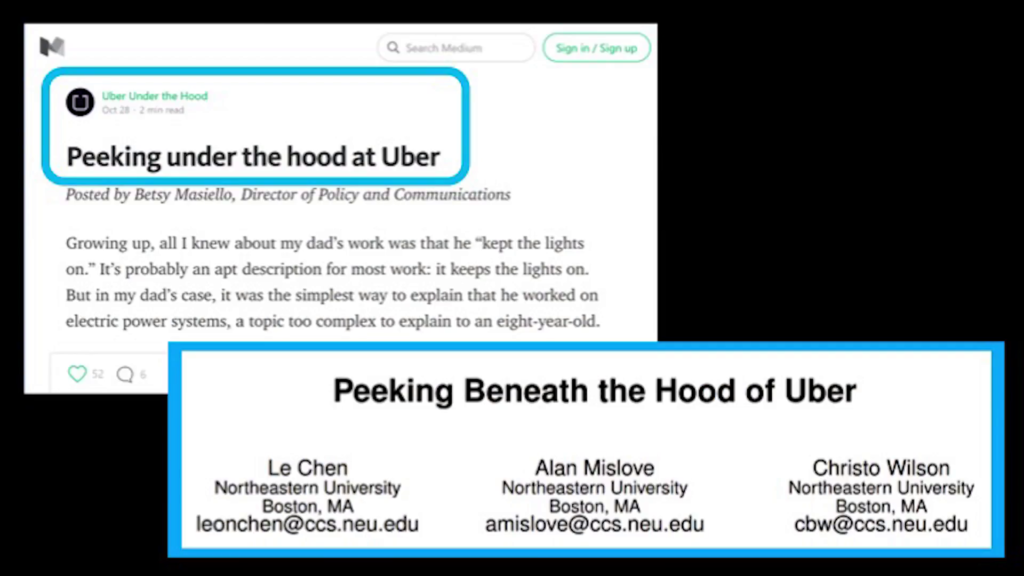

Another positive outcome of our audit was that Uber opened a transparency blog the day our study got published. So this is not you know, full transparency, right. It’s just cracking the window a little bit. But something is better than nothing. I just wish that they had chosen a different title for their blog. You know, emulation is the sincerest form of flattery, but…you know, whatever, it’s fine, right.

So actually what I would like to talk about in a little bit more detail is some of our ongoing work looking at Google search. It feels like social media has sort of gotten most of the blowback from the fake news and the misinformation debacle. But really, Google search remains the primary lens through which people consume and locate content on the Web—much more so even than Facebook to this day. So understanding how Google search works, how it presents content to users, is incredibly important.

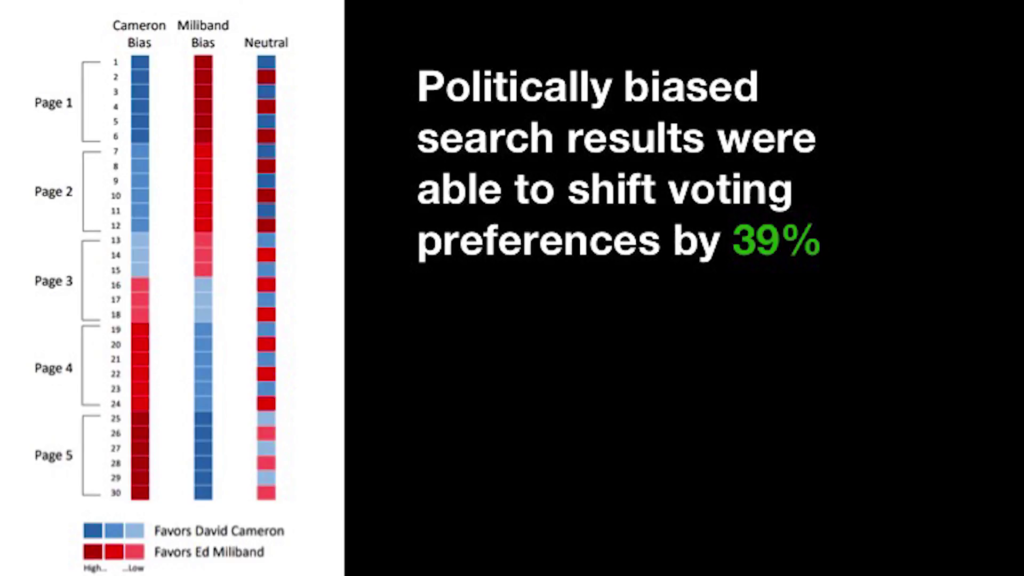

One of my PhD students has been running in-lab experiments where we bring people in and we show them search results that are heavily biased, right. And then we survey them before and after to see if their political beliefs or their perceptions of the candidates have changed.

And the shocking thing is that when you show people heavily-biased search results it can have a very large impact on their perceptions of the candidates. Large enough to even swing people’s voting positions if they were sort of on the fence to begin with.

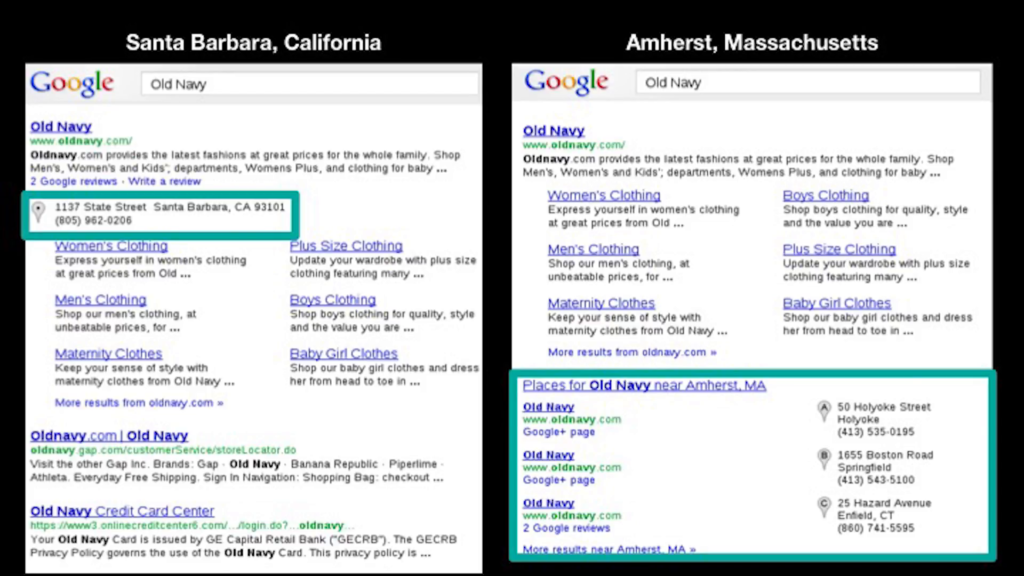

Now, this an in-lab experiment. And I’m not implying that Google is doing anything like this. The problem is that we just don’t know, right. We need to go out and measure Google to see what information they’re actually presenting to people. And that itself, though, is a challenge. I can go write a scraper that runs automated Google searches and collects data, but that’s a fundamentally incomplete picture of what’s coming out of the system. We all know that Google search is heavily personalized.

In this case, these results are different because of location. But there’s other factors like what’s in your Gmail inbox; what have you searched for and clicked on lately; have you interacted with advertisements; that could all potentially impact the output of the search engine. So to really get an understanding of how this system works, the kind of information—especially political information—that it’s displaying to users, we need to enlist your help.

So, in the next couple of months we’re going to be rolling out it’s what we call a collaborative audit. So this is a browser extension that we’re going to try to get people to install that allows us to essentially borrow your cookies. You install it and that gives us the ability to run searches in your browser.

Now, we’re not going to be collecting your searches, and your search history, right. That’s a privacy violation, and super creepy. I just want to borrow your browser so I can run some political searches to see what would Google have shown you given the information they have about you, versus what they would show to me, or Nathan, or anyone else. This kind of collaborative audit gives us the ability to get a sort of broad-ranging view of how the system functions in the real world, track its behavior over time, and ultimately, the next time there’s some kind of crazy fake news controversy, we can look retrospectively and see how did this happen on Google? Who was seeing it? How prevalent is it? What is going on? Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Gathering the Custodians of the Internet: Lessons from the First CivilServant Summit at CivilServant