Hello. Let’s talk about ego. I believe that many projects and organizations today have too much of it, and that it hinders them from doing better design work on products and services. That’s a bit of an accusation, so let me talk you through what makes me say that.

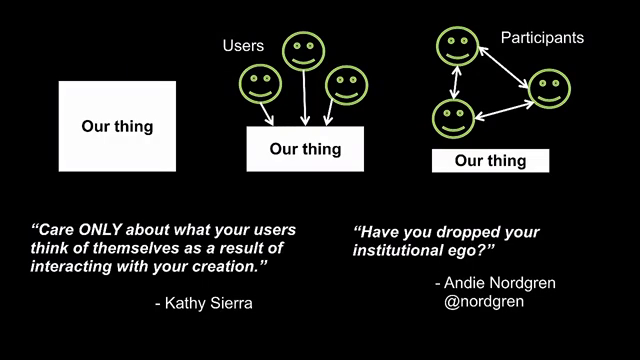

One of my own strongest learning experiences in the past few years started with a few lines of text on a blog. The blog was Creating Passionate Users by Kathy Sierra, and here’s what I read there:

Users shouldn’t think about you.

Do you care what your users think of you?

STOP IT.

Our best advice for creating passionate users is:

Care ONLY about what your users think of themselves as a result of interacting with your creation.

What she’s kind of saying is, stop trying to upgrade and brag about your product and start trying to upgrade your users. This might seem like a small distinction, but for me this was a pretty big facepalm moment. It was just kind of flushworthily embarrassing because I looked at myself in the mirror and realized that a lot of projects, pretty much every project, I had been involved in really wasn’t trying to do this. Even in projects where we used all the user experience methods and personas and user stories and all of this stuff. We were pretty busy with ourselves, and we were thinking about using these methods for upgrading our product, not upgrading our users.

So when I had stopped facepalming and trying to hide from my own embarrassment, I started reflecting and thinking back to the different organizations I had been involved in, and projects and so on. I started thinking about what kind of design focus they had had in light of this perspective shift. And I put together some pictures to talk about it.

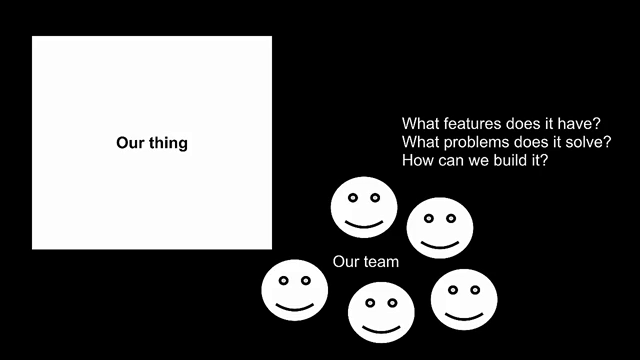

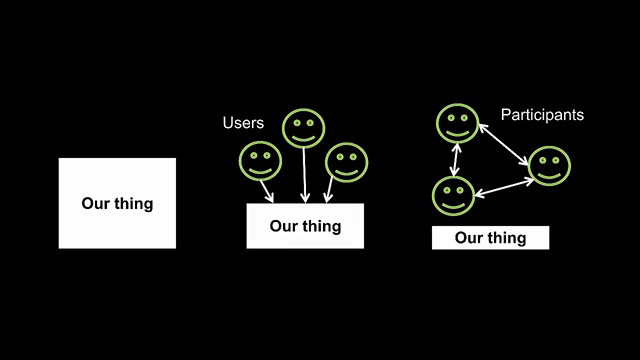

The first kind of organization that I have a lot of experience with was one that was very focused on the thing that they were making. And “the thing” here could be an institution, a library, an event even, but a lot of times of course projects were software or whatever it was. You have some team that’s involved in making it, and typical design questions are stuff like, what features should it have? (Our software or whatever it is.) What problems does it solve? And how can we build it?

And of course the user focus is in there somewhere, implicitly. You’re not building random things just because you like it. Some engineering projects are like that, but you now. And when the user is not very present in the design process, I’m sure all of you have some fun experiences with things that are built like this, when they meet reality and actual users, it can be pretty painful. And unfortunately, a lot of users are on the suffering end of systems built like this. A lot of times when people are using stuff that they don’t really choose whether they get to use it or not, like government systems or whatever it is where the people at the bottom actually interacting with them had no part in making them.

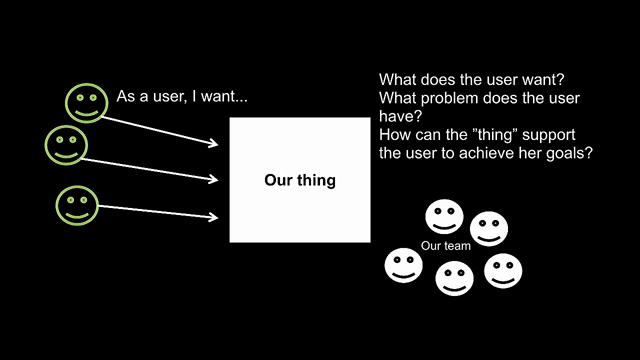

So user experience, design, and these kind of perspectives have brought a hugely well-needed focus shift for design when it comes to making anything, really, that brings the user into view, places the user at the core of the design process, and starts asking design questions that rather look like, what does the user want? What problem does the user have? How can the “thing” support the user to achieve their goals?

For a lot of organizations, this design focus shift still feels radical and like some kind of struggle. A lot of people, especially in design and UX roles, they’re kind of alone in their organizations sometimes, trying to make people just see the light like, “Can’t you see how if we make good user stories, if we use all of these great methods, our thing will be so much better?” And it’s really about taking that move to try and express stuff as what does the user actually want or need, rather than some feature-based list of checkboxes.

I think due to the prevalence of a lot of trends in the software development industry especially around lean and agile and so on, this kind of starting point is pretty common now, at least when it comes to software products. In my experience at least, over the last ten years or so, this has become a sort of new normal. I hope this is not radical to anyone in here, at least. I’m sure you have experience “at home” wherever you’re working where some people think this is a bit of a thing.

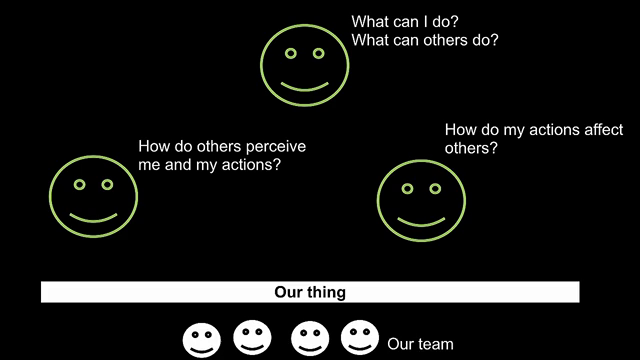

But I also had experience from organizations that were working on things that were very participation-heavy. Some of these things include the game that I work on now, but also huge live-action role playing game projects where hundreds of people have to all play together and take action independently for the thing to even exist. Those projects actually had a pretty different design focus. They were really busy with thinking about the agency of their participation, and common design questions would be more stuff like looking at both groups an individuals, and asking or rather making sure that those groups and individuals had answers to questions such as, what can I do? And, what can others do? And then, my actions if I do them, how will they look to others? How will they be perceived? And will they affect somebody else?

And what we’ve learned in this kind of design focus is that if you don’t have answers to these questions for people, they’re very likely to remain passive. If you don’t understand what you say or the effects of your action, you’re likely to just not do anything. And I think some of the most powerful services out there today, they gave people good answers to these questions.

Twitter, for example. What can I do? Well, I can put 140-characters in this box. What can others do? Okay, they can do the same. How will we see each other? There’s this feed. And the moment Twitter started messing with the properties of this very simple setup, they get pushback from users and so on. Most of those changes I think have been good, eventually.

But the role of organizers or makers with this kind of design focus is really to equip participants with what they need to act in ways that in combination with everyone become interesting or enjoyable situations. I think that this kind of design focus better describes the needs for a lot of services and products today. And in this kind of focus, “the thing,” whatever it is that you’re making, takes even more of a back seat.

If you’re interested in this kind of design focus, which is used in a couple of places that I have a lot of experience with but not necessarily applicable, I’ll give you a few tips, if you’re interested in going more in this direction.

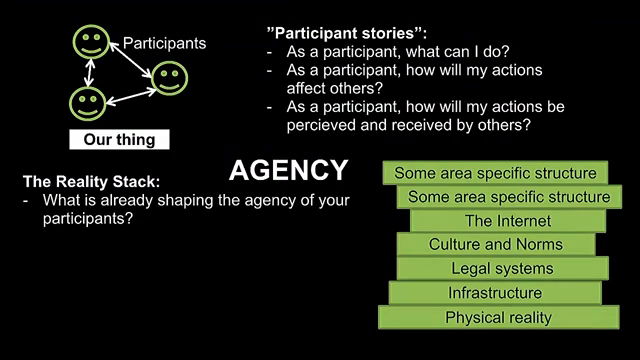

Agency is really a key word, as in “what can I do?” a user/participant/person of your thing, what is it that I can do? That becomes a key design word that I don’t feel is very present in a lot of other design thinking today. A simple thing you can do is to work with participant stories. This is not a radical shift, but if you work a lot with user stories, it does something to your thinking to switch them out for participant stories.

Another tool that I personally use a lot is the concept that I call “The Reality Stack.” This is really something to explore what is already shaping the agency of those people you’re wanting to work with, whatever area you’re in. There’s not one true Reality Stack. This is a perspective that you pick for whatever you’re working with. But at the bottom you might say this physical reality might be difficult to change, but not always. Infrastructure, legal systems, all of these culture norms, all of these things are already there, influencing the agency of whoever you’re dealing with. Then you probably zoom in and get more area-specific. If you’re working in some particular business where companies are buying software for X and you would want them to buy your software instead. You have some more zoomed-in layers where your business skills for your particular area start mattering.

But once you start with agency and then you start thinking what are all the things that influence the agency of the person I’m designing for?, you can start thinking about questions like, how can I equip people with new and interesting agency? And, do I actively need to replace something that’s already shaping agency for people? And maybe then, what can people do now that they couldn’t do without your thing, whatever it is.

So if we’re going to put these three things together, we have a sort of three-phased design focus picture that we can also think of as a little bit of a diagnostic tool for our organization. Where is your design focus, the people you’re working with? What type of design questions are you mostly busy with? Is it about the features, is it about the people in relation to your thing, of being users? Or, are you thinking about people in actual relation to each other?

This view, the participation view, you can of course take it just inside your own thing. You can talk about Twitter, for example, and think of just Twitter users in relation to each other. But very often, it’s interesting to zoom out and think about the person you’re designing for not just in relation to other users of your service, but in relation to the rest of the people in their lives. And that’s where that reality stack becomes interesting. Because you realize that you’re not alone in the room with your user.

I believe that as we work with more and more complex products, that more and more have to do with complex interactions and people doing stuff together and services being platforms for people to meet and do things together, that it’s useful for a lot of projects and organizations to move their design focus more in this direction. All of these positions are valid as main focus positions, depending on what you’re working with. In some very well-known areas where there’s not a lot of uncertainty, being really skilled at just the features of making something is not a bad place to be. So it depends on what you’re doing. But I believe it’s useful for a lot of people today to get out of user mode and really start thinking about people in relation to each other and how you can equip them with agency in interesting ways.

But this is also where that question of ego comes in because I think that there is another necessary movement here, which is about dropping institutional ego. Even with all of the user methods, personas, user stories, all of this, I found (at least for myself and my projects) it was really easy to still be stuck in being pretty self-obsessed. And the embarrassing part for me was that I thought I was pretty good at that user stuff. I felt good about myself. I felt like, “I’ve seen the light. Those stupid people who think it’s all about the tech. I’ve evolved. I’m smarter than that.”

And then this lens that Kathy Sierra put up, this mirror, made me see that it was actually easy for us to be extremely busy with all of these user questions and still be very self-obsessed. I can take a super-simple example for what the perspective shift did for us in terms of dropping ego on game that I work on, EVE Online. We have spaceships, they’re super cool. They’re visually stunning, it looks amazing. And we would do a lot of things with spaceships, pictures, all this kind of stuff where the idea was to make our game look cool. And I think a lot of brands spend a lot of time like this. How are we gonna make our brand look cool? What do we want it to communicate? What do we want people to think about when they see our brand? What colors should it have? What should it look like?

These questions are things that many organizations are very busy with, and I think there’s some stuff that we should just stop doing. Stop self-obsessing so much, because it hinders us. Not that it’s not needed to some degree. But it hinders us from transporting our design focus from people as they related to our thing and further towards that place where we think of people in relation to each other and in relation to their world.

So this is really the question. Is your project or company kind of busy with making yourself look good (which we did, with our spaceships) or can you find a way to spend less energy on that and more energy on trying to actually have your user be good? And this is what we did. We shifted from trying to make the game look cool to thinking about how can we make the person who plays our game look cool. To themselves, to other players, and to the rest of the world. And it produces a dramatic shift in what type of objects like brand-building objects you create and so on.

So this is the question that I want to pose to all of you: Have you got institutional ego? Are you a bit too pleased or happy with either yourself and your user-focus or your institution, your thing, your brand, your product? And what would happen if you could drop it?

This is an attempt to put the gist of this talk in one slide.

Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Description at The Conference’s site of the session this talk was part of.

The original video for this presentation can be found at The Conference’s site.