Saud Al-Zaid: Some of you in the audience have read the write-up for this talk. You probably recognize that I was wrong. And please don’t misunderstand me, that’s not a bad thing. I wish I’m wrong like this everyday for the rest of my life. But unfortunately, I probably won’t be wrong for long.

My prediction was that there would be some form of an attack in the United States or possibly in the foreign territories or interests. My talk would have been a breakdown or dissection and contextualization of the event. And of course, so far in the Trump administration there’s no attack. Well, at least no real ones. Some of us might remember Bowling Green.

The situation is set up in such an awful way. The world we live in seems so unpredictable. I’m sure many of you feel it and that we recognize that even the smallest event could be truly explosive on a planetary scale. Just to tell you a little bit about myself, I’ve been studying this topic, radical Islamic thought and governmental reactions to political radicalism, for about fifteen years now. I’ve done field work and know some of the most influential figures, policymakers, and thinkers in this domain. I’ve had lunch with Osama bin Laden’s secretary from the 80s and 90s, but I’ve also studied with everyone from Madeleine Albright to Slavoj Žižek. I like to joke that I’m one degree of separation from Obama and Osama.

But most of the people who I think are even more important to understanding what will happen after the next attack are not household names. These are diplomats, financiers, military figures, lawyers, politicians, and activists, mostly operating in the Arab world. These can be people whose job description on their business card may not actually fit what they really do in real life. I talked to several people at various lengths, told them about this talk—and you know how I came short—and promised that they would remain anonymous. I asked what they thought would happen, with one constant being Donald Trump, which is…not quite the right constant. Today we’ll have a curated mental exercise to think about what will happen when the unthinkable happens. I will start with background information, then delve into some pretty grim scenarios, and end with prospects in a post-Trump future.

I want to start out very basic here. The first question that comes to mind of course is what is an attack. And this is not as obvious as it may seem. An attack from one point of view can come into rather distinct forms. What I mean here is something very specific, and comes from like the intelligence committee lingo. And they come in two forms.

The lone wolf attack is conceived, planned, and executed largely within one consciousness. It’s one guy—almost 100% of these kinds of attacks are committed by males—decides that the world’s in crisis, and it’s his mission to do something violent. This is the Fort Hood shooting, this is the truck attack in Nice, and even here in the Christmas market in Berlin. And even in my opinion, this is the Boston Marathon shootings and bombing, and what happened in San Bernardino.

The basic idea here is that whatever contact they had with the external world, it was of minimal importance to the execution of the attack. The chat room discussion, that kind of YouTube recruitment video that they had in their browser history, even if they got a little bit of help from someone, that’s actually insignificant because the attack would have happened regardless of that. It is more than one piece of data that explains a person. One pixel does not represent a complete image. In my opinion, lone wolf attacks are best studied within the context of mental health—psychology, psychiatric imbalance, family history—rather than in the context of larger schemata like geopolitics, economics, religion, ideology, or whatever.

The 2016 Orlando shooting at the LGBT club Pulse is the example of this par excellence. The shooter clearly had problems, but the existential status of the global jihad was not one of them. Remember, the most successful lone wolves are actually white guys. Like the Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh and more recently James Holmes, the Dark Knight Aurora shooter.

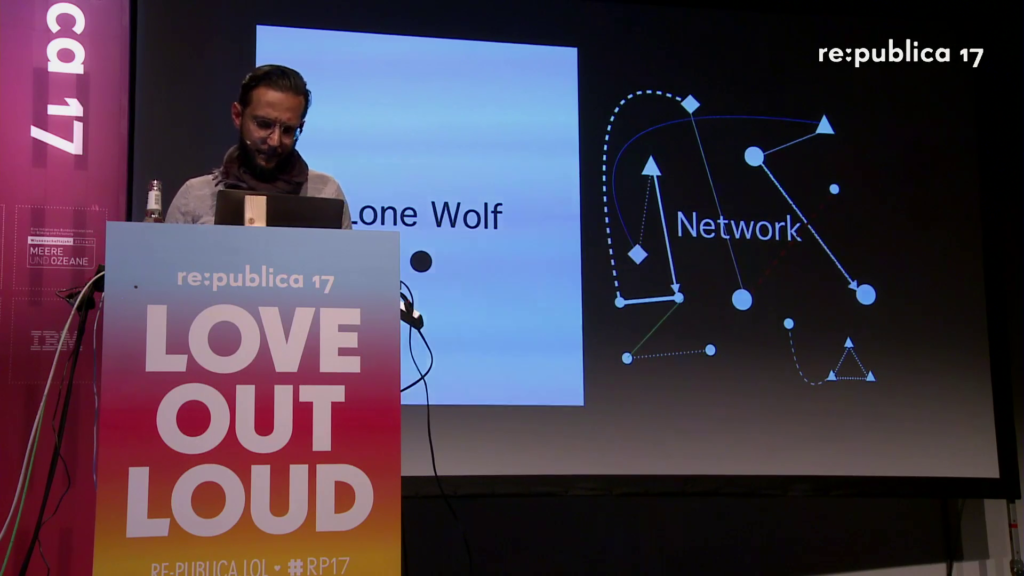

On the other side, the network attack, all the different nodes are important for the planning, execution, and even understanding of the attack. These connections color understanding of what happened and why it happened. And these connections don’t even have to be true, as in the case of Saddam Hussein and 9/11. The worst kind of connections is when someone links two Sunni extremists for instance, like Iran and Hezbollah to Al-Qaeda. This is nonsense, because the Shia and Sunni conflict right now is more or less absolute, unless you come from a non-religious perspective. But there is also nonsense from the other side. For example when Muslims connect Russia with the United States. Ooh. Wait. That actually may be happening now, but I want to get you to the idea that when things are complicated, they need closer and closer analysis.

A network is aware an attack can happen in a way that normal people who are outside the network don’t. And the reasons for this are complicated. Networks can be linked because of shared values or interests, or a shared hostility towards a target. Within that shared hostility, the term agitator means those people who welcome or even encourage an attack, with everyone from religious figures giving sermons to relatives, friends, strangers on the street or on the Internet. Anyone who encourages some kind of action.

Enablers are more linked to the attack because their support was critical for the execution of the attack. Though agitators can be enablers by providing financial or logistical support, some enablers may simply be helping the attack for other reasons, such as to make money. If the enabler is in the black market for guns or explosives, they can be indifferent to the cause. The primary concern for them is of course making money.

Last but definitely not least you have the fighters who execute the attack. And I say “fighters” and not terrorists or jihadis; I don’t even like the word “combatant” because that would include some agitators though not certain enablers. I think we need a simpler term for those guys who are committing the violence, and “fighters” fits the bill on an analytical level.

Fighters supported by a network is why the attacks in Paris, for instance in the Bataclan was significantly different from the attack in the night club in Orlando. When things get complicated, I like to rely on theoretical frameworks that can handle complexity. And none are more complicated than Niklas Luhmann and his systems, as some of you might know. If you know Luhmann, then you know I can kill this room with boredom faster than you can say “sociocybernetics,” but I promise you I won’t—I’ll try not to at last.

A network is a kind of social system. Luhmann’s idea is that a social system becomes self-aware through communication, and through making a distinction between itself and its environment. If the same message is communicated over and over again, that distinction becomes stronger and stronger. What I want you to imagine is how Muslims are thinking of themselves and their environment with the rise of Trump and other hypernationalist movements. And I want you to think of Trump himself as a reality television star.

Some of Luhmann’s most important work revolves around the idea of the reality of the mass media. How things are made real by repetition and distribution. For Luhmann, the number of copies of a piece of media, the number of times it gets duplicated, is important. Even if not all the pieces are consumed. So say if a trashy newspaper is printed in large enough numbers, even if it isn’t read, the fact that there are a million copies circulating matters to the construction of reality. So, all those copies of Bild, or Sun, or those—you know, newspapers you don’t actually read, they influence the world around you in a significant way. This was a development, or really a break, from Marshall McLuhan’s “the media is the message” to being something more like an equation, or “media times distribution equals the message.” Repetition here is the important factor.

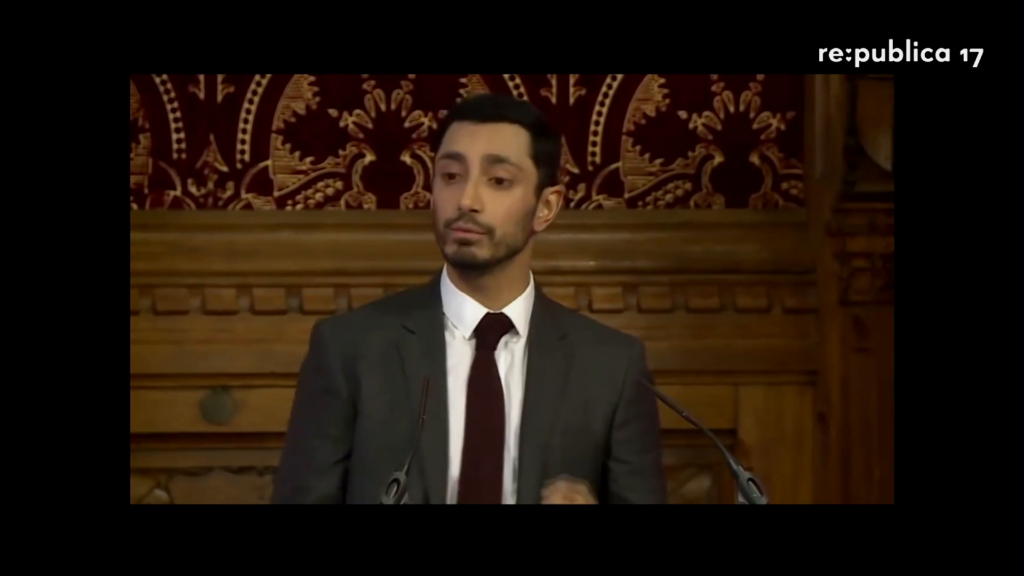

And this is Riz Ahmed. You may know him from recent shows like The Night Of or the hip hop group The Sweatshop Boys. Or even further back, the best film ever made about terrorism in Europe, Four Lions, which I highly highly recommend. Here he is to British Parliament about the representation of Muslims in British media. And this really sums up the situation I’m trying to describe quite nicely from the Muslim side. [plays video clip]

Every time you see yourself in a magazine, a billboard, TV, film, it’s a message that you matter. You’re part of the national story. That you’re valued. If you represented. Now. if we fail to represent people in our mainstream narratives, they’ll switch off. They’ll retreat to fringe narratives, to filter bubbles online, and sometimes even off to Syria. In the mind of the ISIS recruit, he’s a version of James Bond, right. In their mind everyone thinks they’re the good guy. Have you seen some of these ISIS propaganda videos? They’re cut like action movies. Where’s the counternarrative? Where are we telling these kids that they can be heroes in our stories? That they’re valued?

I saw an interesting survey recently. It was a Gallup poll. It was a survey of a billion Muslims. And it took years and years to get done. I’m citing [?]. And it was really interesting. They asked a billion Muslims what are their key grievances with the quote-unquote West; I have problems with that term. But, what are their key grievances.

And number one was—conversation for another day. You know, the disconnect between the West’s stated values and their foreign policy. We’ll talk about that another day, if you invite me back. But number two on their list of grievances was the depiction of Muslims in the media.

Riz Ahmed

In a talk I gave them the last Chaos Congress, I discussed the depiction of Muslim and Arab males in video games, particularly first-person shooters. My thesis is the clash of digitalizations. It’s a response to Samuel Huntington’s clash of civilization idea. It is about the danger of when people start interpreting things in this kind of black and white. When we repeat the message over and over again in all forms of media. Both sides to do this, not just the West. This is light versus darkness, this is in Arabic nūr versus jāhilīyah, this is the kind of discourse that gets us nowhere closer to the truth of the conflict, it is quite literally what fuels the fire.

For me, this begs the question what is civilization? Is it the ability to invade two-thirds of the world? No. It isn’t. Civilization is the ability to bring peace and prosperity to the world that it had not seen before. The forces that drive us away from this vision of progress are diverse. And they are riddled by misunderstanding, greed, and above all ignorance. Which to me is the real meaning of barbarism. It’s the real jāhilīyah.

The crazy situation we find ourselves in definitely sees the world in negative terms. The thinking goes, if the Muslim world can’t get civilized, then populist, racist political movements in the US and Europe will gain power over the military and force them into submission. A domestic attack is the perfect reason to do so. Virtually the first thing the Trump administration did when it came to power was enforce the Muslim ban to travel into the United States. I feel with an attack this kind of policy will increase tremendously. Even today, the banning of laptops and tablets on flights from the Gulf are an obvious example of racism disguising itself as protective paranoia.

Comparing the two presidencies of course is difficult, because they have such radically different personalities. If the Obama doctrine can be summarized it, “Don’t do stupid shit.” Both presidents inherited significant conflicts and infrastructure to handle those conflicts. The intelligence/military symbiosis had definite ideas about how to wage the war, with mass surveillance and expansive wars. What Obama chose to do is only to succumb to those targets that were pushed upon him that maximized return in terms of gains.

Unfortunately this largely backfired. This is [?] al-Awlaki, an American imam who was killed in a drone strike in Yemen and is now the leading figure of jihad on YouTube, after he’s dead. He’s the kind of theorist of the lone wolf attacks in jihadi thought because he himself went through a lot of surveillance. His basic message for wannabe jihadis is that you don’t trust anyone. If you want to go on a suicide mission, you just go ahead and do it. Don’t tell anyone ahead of time. Thus it was a clear factor he was an influence to the Fort Hood shooter—who actually tried to contact him—and also the couple from San Bernadino. He’s a figure that would normally be condemned by mainstream Muslims, except he was killed by a drone strike without trial. The first US citizen on record since the American Civil War, along with his son, who was also killed during Obama’s time, and his daughter who was killed in the first Special Forces mission ordered by Donald Trump. This is the very definition of doing stupid shit. And the fact that there was no trial or major public inquiry into the matter is a massive sore insult to the Muslim community around the world.

This over here is Erik Prince. The picture he is showing is what he does for a living. Some of you might know the name Blackwater. That’s the company he founded and then renamed many times. Prince is the son of a billionaire. He’s also an ex Navy SEAL, one of the most elite special operation units in the US military. If the American presidency is a kind of game of thrones, then Erik Prince is…Jaime Lannister. Like Jamie, Erik Prince served multiple reigns, but of course they have a favorite, his House Lannister. His family donated millions to the Trump campaign, and his sister is Betsy DeVos, the current Education Secretary. It’s funny, sisters are kind of a touchy subject in the Game of Thrones show as well. Touchy-feely, maybe.

Prince started training American law enforcement, focused on school shootings after Columbine. But he became the head of the biggest mercenary network. This happened after 9/11 with support from Cheney, Rumsfeld, and the CIA. The reason his business grew was because of the possibility for deniability, particularly when things go wrong. The way it was modeled is that they had contractors and subcontractors as a way to disperse blame an to have these kind of covert assassinations that were technically against the law.

He is someone who has Top Secret clearance, the ear of President Trump, and according to some reports he’s become a kind of secret envoy for the President. He also happens to be under investigation in four different countries for war crimes. Many of the people I talked to actually kept mentioning Erik Prince. He’s a mercenary, a paid fighter in a war, and a libertarian who believes in limited government.

Though initially supported by Cheney and Rumsfeld his operation expanded along with the expansion of the War on Terror. And now he’s the most influential private military contractor, even bigger than the companies you may be familiar with. Prince wants to see the privatization of special forces and security, basically the most sensitive parts of a modern state. He’s even quoted as saying that he wants Blackwater to do to the military what FedEx the to the Postal Service.

Blackwater went through extensive rebranding since their fighters shot up innocent civilians in a crowded market in Iraq. Besides having their own drone program, Prince is now building his own air force that would be capable of dropping bombs. And this begs several questions, the first of which can corporations wage war? Also, isn’t peace then bad for business? If there are no wars to fight, then what will these guys do, you know.

And at this point its particularly interesting because some of the most important generals in ISIS were trained by Blackwater. This is Abu Omar al-Shishani, who’s actually from Georgia in the Black Sea, and he was trained as part of the Islamic moderate rebels against

Bashar al-Assad. The second he crossed the border from Iraq to Syria he joined the group Jabhat al-Nusra, which was the first allied with Al-Qaeda and would eventually become ISIS. This is the very definition of stupid shit.

And the stupidity gets better somehow in the Trump era. This is Sebastian Gorka, the most public White House expert on radical Islam and Deputy Assistant to President Trump. There’s some significant evidence that he’s connected to an antisemitic organization in Hungary. Gorka has suggested that an appropriate reaction to a terrorist attack in the United States is to bomb the grand shrine in Mecca. This is the most important location in Islam, the direction Muslims pray to five times a day. And I want to emphasize this. This is one of the leading experts on radical Islam in the Trump administration.

Unfortunately, the best experts on Islamic jihad are currently too busy fighting each other. These are the two French academics Olivier Roy Giles Kepel, and they are at a very public tête-à-tête. Olivier Roy believes that radicalism is being Islamized, or basically that the majority of attacks are being done by thugs using Islamic rhetoric to justify their violence. It’s a paradigm that’s more akin to criminology. Kepel on the other hand sees the problem to be within Islam itself. That is, Islam is being radicalized because the progressive West is too easy on Islamic conservatism, which is creating a bubble within Europe and kind of a structural stress to the system.

I think both are functionally wrong because they’re not paying attention to the larger scope of the problem. Not just focusing on the social system, to use Luhmann’s term, but also in the global environment the system is operating from, the media young Muslims are exposed to reinforces their alienation. The constant security region that physically searches their person when they go to an airport, or virtually infects their computers and phones with surveillance software. It’s interesting to hear reports from ISIS fighters about how free they feel themselves to be when they’re in the Islamic State. That they can finally breathe and so on. Fighting the problem is a big part of the problem, and this kind of lack of reflexive realization is really an issue.

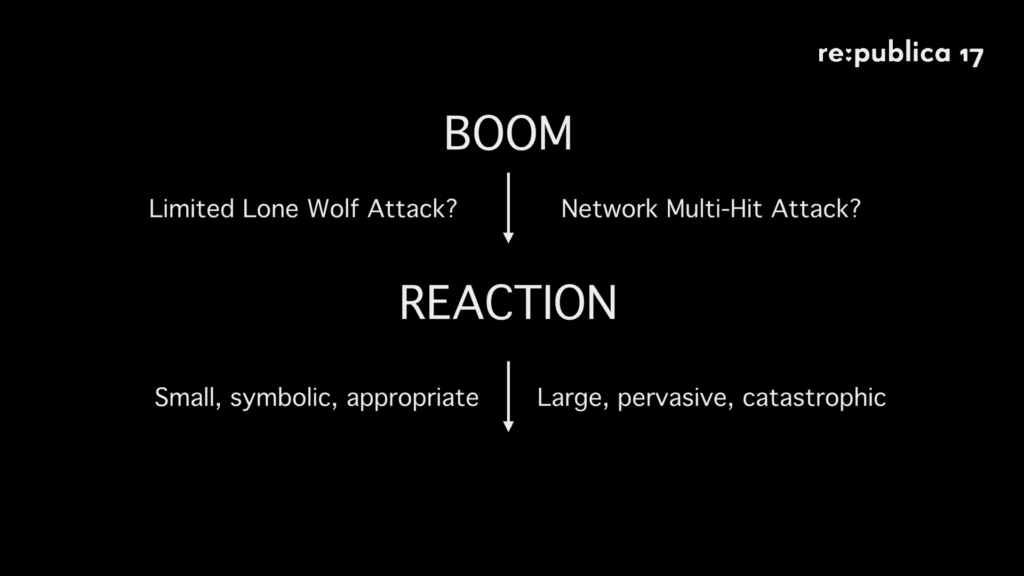

And here I want people in the audience to think about the next attack in this kind of way. Like boom, was it a limited lone wolf attack, or was it a network multi-hit attacked like September 11. This makes a difference. Because the reaction can be either small, symbolic, and appropriate—which I don’t think anyone’s expecting from the Trump administration. Or it’s going to be a large, pervasive, and catastrophic.

The worst-case scenario is not so much the attack, it’s the aftermath of the attack. What will the Trump administration do? Will someone like Gorka sway the situation room to bomb Mecca? But this is literally the stupidest thing they can do, as 1.6 billion Muslims will basically begin rioting in unison.

But let’s think about the second stupidest thing, which is repeating the George W. Bush formula of invading another country. As Frank Rieger, the spokesman for the Chaos Computer Club recently discussed, the price of oil may be the major factor in the future conflict between the US and the rest of the world. And he spoke in the context of North Korea, Russia, and China. But it’s equally true for the Middle East.

Currently there’s a proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia and Yemen. And a lot of the predictions I’m hearing is that Yemen, even more so than Syria, is the prime candidate for America’s next intervention in the Middle East. The reason should be obvious from this picture, because if you stop the vessels going through the Suez Canal…almost half the world’s oil goes through this route, and much of the world’s trade.

And if you think this sounds crazy, consider that President Trump’s first foreign trip is the Saudi Arabia. I know he’s known for being unpredictable but this kind of Abrahamic religions tour…you know, Saudi, Israel, Vatican…I don’t think it’s just silly symbolism. And other people agree that the Western economy right now is thriving because of the low price of oil.

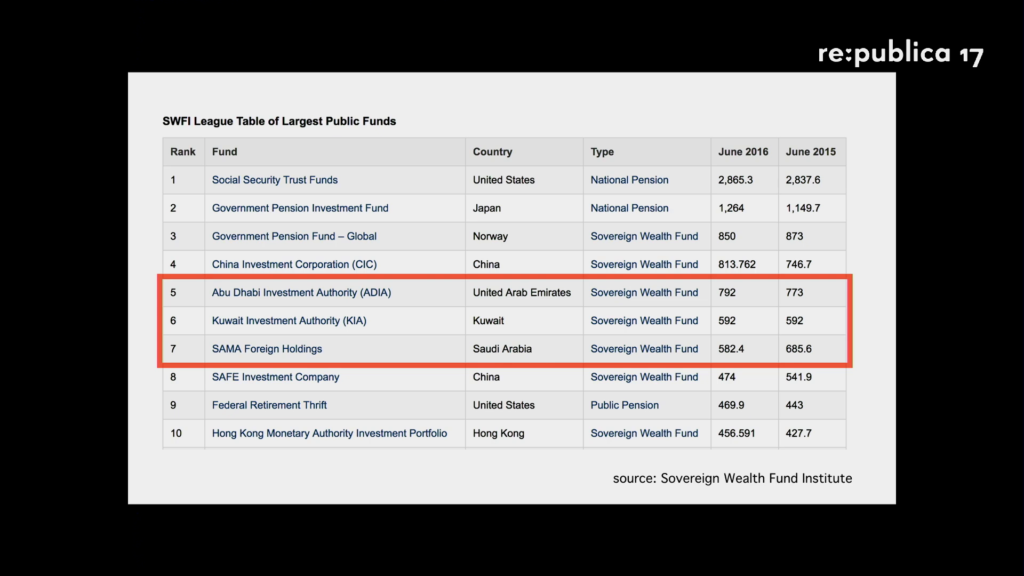

Of the top ten countries with proven oil reserves, six are Muslim majority countries. Two of them are Venezuela and Russia. So in the case of an all-out war, America has to rely on its own oil and Canada—which is shale and now mostly fracking, so it’s pretty expensive. And one of the scenarios that was largely discussed was that the sovereign wealth funds of the oil-rich states would deinvest from the United States. And the Gulf economies are also the top investors in the current economic order. Of the largest public funds five through seven are from oil-rich states. And also fourteen; sorry Qatar.

Most of the investment is in the United States and in Western Europe. If these Muslim countries feel threatened by the idiocy, by the privatization of the conflict along their borders, many of them have spoken to—kept going through the scenario of deinvesting from the West, even at a loss, as a form of influencing policy. The big worry is that something like the Islamic State is here to stay in the Iraq/Syria region. No matter how the war is waged, the most alienated Muslims in the world will find themselves there. And this presents a fear for neighboring states. Most of the financial support to their kind of neighboring existential threat is coming from their own subjects. These regimes are paying for stability, and if they don’t get their money’s worth they’ll have to find other sources of stability.

Right now, the opposition sheikhs of Twitter…this strategy would completely satisfy the Islamic opposition in the Gulf. I know there is this image of radical Muslims in the Gulf kind of financially supporting ISIS, but the trend isn’t that clear. This was true from 2011 to 2015. They now see ISIS and Daesh as a Western plot to make their movement look bad. They discuss the prevalence of recent converts, their access to Western weapon systems, and they really split hairs with them on doctrinal issues like the caliphate. After all, after the fall of the brotherhood in Egypt they kind of are rightfully pessimistic about like, the “democratization of the Middle East.” For them, violence done in the name of Islam is not Islamic, it is rather a symptom of the problems in the Arab world after the so-called Arab Spring. Figures like Hakim [?], who is usually sympathetic to radical Islamic liberation movements calls Daesh counter revolutionaries. Another sheikh called Hamid [?] says he regrets raising millions to the Syrian opposition without knowing more about their views.

When they see the allegations of Trump colluding with Putin, their reaction is “We’ve been saying this all along.” Erik Prince now actually has a residence in Abu Dhabi, where he’s in close contact with the crown prince, and apparently China is now a big investor in his security business. But is it a really security business, or merely a business focused on keeping a state of perpetual war and low oil prices?

It’s okay to be wrong about forecasting the future. It’s not okay as members of civilized societies to suspend our most closely-held values because of contingency. Or more officially phrased, a state of emergency. This clearly will not end in the next four years. But what we will see is the most ridiculous expressions of emergency law. We’re already seeing it. And hence, if you work in security, if you work in the legal, political, bureaucratic, or military fields, don’t focus on the emergency as much as you should focus on the situation or the person at hand, the person in front of you, and how to get them through this without making the situation worse. Without increasing the alienation. That’s an intelligent way to get through the next four years. And then maybe we can support a realistic candidate that can genuinely be a conduit for peace. Activists need to keep this in mind when they decide on how to support a candidate if they care about the future of peace. And sorry, I’m not that optimistic about Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump kind of solving the Middle East issue right now, so…neither should you.

I truly believe in the long term that the path to peace will take the form of a truth and reconciliation commission, analyzing and ending once and for all the War on Terror. It will be global in scope, and the truth part will start on accurate figures on the number of casualties sustained in the Muslim world during the War on Terror. The reconciliation should take the form of financial and logistical compensation for the death and destruction that wasn’t already inflicted. Currently the war in Afghanistan has cost more in today’s dollar than the Marshall Plan did to rebuild Europe after World War II. The Marshall Plan infused cash to sixteen European countries that had far more complicated economies—in 1945—than Afghanistan is today. This kind of war where marines carry duffel bags full of cash to warlords to appease them and to secure their flimsy alliance to the United States has only added more fuel to the fire. And today Afghanistan is one of the most corrupt countries on the planet.

This is clearly not the values of the West’s broadly defined. You guys stopped fighting each other after World War II, but you need to stop fighting your other others. You make choices with the media you consume as well as the media you condone. When you see a show that depicts young Muslim men as de facto terrorists, you need to reject that show as racist and to be repulsed by it as if you saw an antisemitic show or a show that’s racist towards black people. This repulsion needs to come from the same source as your fear about a terrorist attack, because they are connected.

People like Trump, people like Marine Le Pen—thankfully—Geert Wilders, maybe their time is up, but they still have time to kind of cause significant damage. And it’s our time to think about the future after the next attack, and not so much obsess about the fear of the attack itself. Thank you very much.

Moderator: Thank you very much, Saud, on this talk. Are there any questions to Saud?

Audience 1: Hello. So, I’ve never heard of a sovereign wealth fund, so excuse my ignorance, but at one point you said that oil-rich countries will stop investing in it because they invest in it because they value security around their neighbors. So my question is, isn’t Saudi Arabia for example also funding ISIS or some other group in that war, in that region?

Saud Al-Zaid: This is kind of a misunderstanding that they did fund in the beginning of the Arab Spring anything that was anti Bashar al-Assad. The proxy war that was actually happening in Iraq was kind of a different, free-ranging conflict where they were more interested in the safety of Sunnis living in Iraq. And this wasn’t small sums of money, but it also wasn’t a continuous check. And it didn’t seem to have come with influence that wasn’t kind of superficial. So them declaring the caliphate very much goes against the official Saudi regime’s view of itself and view of the world. The idea that in the past they funded ISIS, will they fund in the future, and currently it’s not looking that way at all. It’s looking like it’s almost now an autonomous unit that can self-sustain by selling oil on the black market, for instance.

The idea that they are ideologically aligned is actually misinformed. I don’t think that Saudi Arabia wants to have an Islamic state, because they’re nervous that it would expand to Saudi Arabia, naturally. And here you have to make a distinction between say, the Saudi people or the Saudi regime, and of course you’re talking about very large groups. And there is a small percentage in Saudi Arabia, in the Gulf, that do support ISIS but I think those numbers are actually comparable to what you have in Europe, more or less. That the actual Saudi regime, like the Minister of Defense probably wants ISIS to go away more than anyone else. I hope that answers your question.

Moderator: We are to your right, Saud, and there’s another question.

Audience 2: Hi. So my question is more about social media. So we know that ISIS and other radicalist groups recruit from there, but we also know that the right-wing nationalists live on Twitter and are very happy there. So, in terms of curbing that using technological measures… So we can detect racism and we can detect right-wing rhetorics and Islamic rhetorics, how do you think those kind of tool should work without…really censoring the freedom of speech and taking that into account?

Al-Zaid: So, my point of view about it is that freedom of speech is a central human right value that I don’t necessarily in my own work kind of negotiate with. The way I look at the problem is actually more aggregate social feelings, as it were, at the other end. And I think the true origins of these negative feelings is feelings of being disgraced, of being at a disadvantage, of being alienated. And like the Riz Ahmed quote like, the idea that when they see heroes in ISIS, that they feel sympathetical to the cause, and maybe even alt-right like the 4chans and whatever, when they see Donald Trump and everyone’s against them, it gives them the sense of group feeling. And I’m more interested in how to diffuse those feelings, and I think that governments have a lot of agency to actually do this. And instead of spending trillions on military infrastructure, they should maybe spend it on infrastructure infrastructure, or projects to keep you know, the Muslim world kind of afloat. In a kind of…in the model of the Marshall Plan. That instead of repeating the World War I and World War II, they were like you know what, let’s keep the Germans busy to build their Autobahns and other things. I think a similar thing has to happen in the Arab world, and a real kind of honest reflection and income redistribution. And this might be actually… Some imams who are pro…kind of in a weird way pro-Trump because he’s the accelerationist candidate. They want their own regions to realize that maybe United States isn’t the best ally to have and that this will eventually kind of say hey, maybe we need to invest in other things than the United States.

I don’t look forward to an Internet that’s censored. And I hope it doesn’t. But I think there… There are other experts here that actually do this specific thing.

Audience 3: Thank you very much for this really great and interesting talk. You mentioned the Marshall Plan, and that something needs to be part of a truth and reconciliation process, a thought that I find very interesting. A key element for the Marshall Plan, at least in Western Europe, was that money went into functioning or starting-to-function democracies. So the money was not spend in non-democratic society, at least in Western Europe. So, what’s the connection with your idea of a Marshall Fund 2.0, and democratization in the Middle East?

Al-Zaid: I hate to say this because I think it should be self-evident that we have the technology to have even a more advanced system than the Marshall Plan. So for instance one of the largest backers for Transparency International is actually Kuwait, which has a lot of corruption. But there are in a sense local civic society organizations that are really really pissed off at the duffel bags full of cash exchanging hands. And that if we actually had a system where we tracked dollar by dollar where things are going and how they’re being spent that this could be done in a way better administrated than the Marshall Plan, say. It’s kind of heartbreaking that instead of that, they give it to Blackwater, who gives it too a hundred mercenaries, who gives it to another you know, like— The idea is that this isn’t helping. This is actually part of the problem, and we need to in a sense be convinced of our own rhetoric which I think is really a problem of the democratization narrative after the Arab Spring. That people didn’t think that Cairo or Egypt would be ready for democracy. And that we didn’t give the Morsi experiment the chance to play itself out. Which maybe now in retrospect was a bad idea.

Audience 4: Thank you very much for your talk. I like this idea of clash of digitalizations much. Its a very nice word to remember. I have just one question. You talk about alienation from people living in the US or in the West, Muslim population. But what about the people from Tunisia or Saudi Arabia? So a lot of them are going to Daesh and they are not the poorest ones. So, how can you explain this fact?

Al-Zaid: Tunisia is actually a super interesting case, because it’s actually—of the Arab recruits, some statistics say that Tunisians are the most, and Tunisians have been involved in a lot of the terrorist attacks also in Europe in the Bataclan on and so forth. And the Arab Spring also started in Tunisia with the self-immolation. But it’s one of those things that’s understudied, to understand why it’s going on in Tunisia. And part of the reason from my point of view is because a big part of the Palestinian refugee community lives in Tunisia, that this is actually kind of a factor that they see the injustice very much first-hand. And the Palestinians in Tunisia are integrating in a way that they’re not in other places, so I think this also shows you how the Israeli-Palestinian crisis is still kind of one of the strong fissure points. And to understand it in the context of the 21st century is actually really complicated. But yeah, Tunisia is a point of conflict both in the Middle East and in Europe, and we need to understand it. We simply don’t.

Audience 5: Hi. You pointed out I think quite correctly that one of the major problems with this whole issue is the representation and the perception of young Muslims in the Western society. And I was wondering what your reaction for example when the travel ban first came down, and when the immediate response in the US was you had protesters shutting down major airports and basically saying “No, we’re not having any of that.” And the courts than saying “We actually can’t do this, president or not.” Do you think this is a step in the right direction?

Al-Zaid: So, I think the protest movement has to keep going and has to do it at a very high register, and I’m sort of nervous that they can’t maintain it. When the first travel ban happened, I travel very frequently between United States and Kuwait and Germany, and I got very nervous and paranoid even about flying in. And thankfully I didn’t have any problems but the first time I flew in, I felt there was a lot of attention from my friends on the other side. But then after the second or third time my friends were like “Hey, we don’t need to pick you up from the airport anymore.” And this is actually like you know, when you put your guard down this might be when it’s most dangerous as, it were. Especially me because I do these public talks that sometimes get attention.

And this is kind of making me nervous. So like, the ACLU, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, all these civil society things have to worry about fatigue. I think because they’re going to encounter a lot of case law for specific instances. And they have to develop new systems to get through the four years and possibly longer, and other infrastructures to set up regime change in the United States. Hopefully.

Moderator: Thank you very much, I didn’t see— Oh yeah. There’s another question. We still have some time left. And I think it’s a topic worth investigating.

Audience 6: Hello. So my question is why did you name your whole presentation Terrorism in the Trump era? Like what is going to be so specific? What is strong going to do that’s so interesting that he deserves your attention if there is a terrorist attack in the United States? Compare this to the times of Obama or Hillary Clinton if she was chosen.

Al-Zaid: I think the major thing is the potential for overreaction. Especially because he’s surrounded himself with military generals that will in a way— The distribution of the American military system is that there’s a civilian branch and a military branch, but now ex-generals are in charge of the civilian branch. So they’re very in a way oriented toward making missions, and doing things that are on an active level rather than say diplomacy or thinking about longer-term repercussions. And it shows you like— My impression or the read or the White House was that the Awlaki case file was very much pushed in Obama’s face until he actually authorized it. And it’s clear that they wanted to “finish it off” when Trump came into power and Awlaki’s daughter died right after that.

I think the Trump era will be more trigger-happy in these kind of limited attacks, the same system that Obama set up. But the real fear is the Bannon Strategic Initiative office which is changing the entire idea between the Chief of Staff and sort of a more decisionmaking process. And we’re seeing that Trump is being pulled away from this stuff, but also when he’s put in a corner seems to take advice from people who are not authorized. And figures like Erik Prince is someone you should maybe focus more about, that it’s going to be hyperprivatized. And there’s going to be a lot of deniability over like no, America didn’t do anything; these were…some company or whatever. And I think this will actually start looking more and more like Arabic private security firms. So you’re going to have these private mercenaries that look like it’s an Arabic firm doing missions in Syria, Iraq, or whatever, and they’re going to have zero oversight from the United States even though, not to get too conspiratorial, but this is where it looks like it’s heading. Him moving to Abu Dhabi is evidence to this. And setting up an investment firm that’s connected with China is also highly suspicious.

And to predict the unpredictable is kind of a losing game, right. That you really can’t predict what you can’t think about it, because it’s unthinkable by definition. But I want to set up a system of thought, or a way for people—like normal people—to think about say hey, is this a crazy person who just shot up a club in some city, or is this a coordinated attack with multiple people and needed very strategic equipment and all this stuff. And this makes a difference, right. It gives you an idea of how competent people are reacting to the current situation. So this is why the Trump era I do believe it going to be different than Obama. And I hope not. I hope somehow that this restraint will continue, but I’m not that optimistic unfortunately. so.

Audience 7: Hi. I have some issues with your talk so I’ll pick one. I think it’s very tempting to look at these conflicts and pick names and then describe the conflict by pointing at some persons. And that gives us all the impression as if there were some key players who push a conflict in a certain direction and who actively propagate a conflict in a certain way. Looking at someone like Erik Prince, yeah, that’s very tempting. It’s good branding. Blackwater’s this name most of us recognize in one way or the other. The fact is that companies like Blackwater have existed for the last thirty years in many places around the globe, outside our perception because they’re not as well branded, in a way. And they happen to act more in places like Africa.

But if you then look at these conflicts and point out key players, it becomes like this…a little bit tainted like a conspiracy theory. That there are key players and they work together. But the whole thing— I’ve worked on this issue myself for quite some time and have a presentation the day after tomorrow on somewhat of that topic. The problem with this conflict is that everyone, even the people involved, think they play the system, and play the game, and they control everyone around them. And then that creates vacuums for groups like ISIS. They fill by chance. It’s more a coincidence that ISIS comes into power. And suddenly we have to deal with it.

So I think it’s very problematic if you then happen— And they act with those people, and they w— We never get to a good conclusion on that if we try to understand this conflict in a way where we have the key player who brought us here, actively.

Al-Zaid: Good question, and the way I would respond is I look at how the system is incentivized. What does it mean in the post-Cold War world that the largest employer in the world is the United States Department of Defense? That has the largest budget of any single entity. And what does it mean when you have people who are profiteers of war? What’s their incentive structure? And the metaphor you usually hear policy analysts talking about is that they describe them like doctors.

So when doctors cure a patient, they have other patients to cure, correct? But in this case, in the Middle East in particular, the patient seems to be kept in a sick state. That the amount of money that is being circulated both for…on paper, causing stability in the region versus the oil output that is coming from the region, is in a way…that there is a margin of profiteering that is just higher. That why is there a black market of oil? How can we— You know, they can search every part of your body but yet they can’t locate oil tankers that are coming out of the Islamic State seems absurd. That these resources aren’t allocated properly, on just the most basic level.

And you’re right, picking on Erik Prince is kind of in a way easy. But he has been an innovator in this field, in the same way like you would say Steve Jobs has been with smartphones. That he’s really changed how people think about the private military contractor. That it wasn’t these big companies that are parts of like Halliburton or McDonnell Douglas or whatever, that these guys aren’t just creating infrastructure, that these guys are actually providing military strategic objectives on demand, you know. From taking out someone to managing a secret prison. Which is the different requirements of a terrorism era than a Cold War era, for instance, right. Like there’s no need for nuclear arsenals and so forth. You need more like these fast movements.

And you’re right, it’s not an easy…one-to-one to blame Erik Prince for all of these problems. He’s reacting to the times but he’s also profiteering from it. I was in a way tempted also to bring up Bannon, and to bring up other figures that are causing ideological issues to be in play. And I think they need to be scrutinized. I really do. I think the press needs to do a better job of reporting the connections. For instance, the San Bernadino shooter, his brother works for Blackwater. I’m not saying this in a conspiratorial tone, I’m just saying this is an environment of heightened and profiteering violence.

Audience 7: You mentioned yourself that you’re one degree away from Obama and Osama. And now you bring up these degrees of separation. [crosstalk] That doesn’t—

Al-Zaid: Mm hm. Yeah. I am a product of—

Audience 7: No, but that brings you— If I do a presentation I could say well I heard this guy Saud Al-Azaid say he’s also connected to these people. That doesn’t really help. That creates this environment of conspiracies. These guys, like— These are stupid idiots like Gorka. They’re just crazy people. Now with the media environment we’re in, people start listening to them. They’re just— They have no idea what they’re talking about. And so now we surround them, we envelope them in this conspiracy fear that’s just not there.

Al-Zaid: We shouldn’t let them operate in the shadows. And you’re right. My degrees of separation cause me to get searched in various places, to get scrutinized by intelligence networks in different ways. It definitely colors my view of the conflict, you know. And to say— In a way I think you’re doing this kind of scientific thing where in objective reality, if you look at things in a laboratory… I don’t think that’s how it works. I think feelings and how people are approaching the issue really much colors this conflict. I think this is largely an emotional battlefield. [audience applauds]

And I look forward to your talk. I’m definitely coming now, so.

Audience 8: Hi there. Taking a step back at the national level of different countries, the USA for example, what are your thoughts on how easy and how simple it can be for people to access guns, smaller arms generally, and then use them in very destructive ways and settings?

Al-Zaid: Definitely. Like again, to go back to a theme, “we have the technology,” right. A single iPhone can track every manufactured bullet in this world. That you have an identification number and you can show this chain of transmission. We have the computing power to do this yet we choose not to. Small arms is like a growth industry right now in Belgium and Austria and so forth. And these are weapons that are ending up in the battlefield. And so as civil society we need to be demanding not just from like the United States, but from your Western European countries like hey, who are we selling these guns to? Can we have more oversight about who gets them and what context? And even if you only do it for 5 or 10% of small arms, I think you can still in a way make a dent in understanding how this black shadowy market is working. Yeah, I hope that answers.

Moderator: Okay. Thank you very much Saud Al-Zaid.

Al-Zaid: Thank you all so much for staying.