Daniel Barber: So, fabulous. Great to be here. Thanks to the organizers for the invitation. Thanks of course to all of you for your attention, and I look forward to the discussions we’re going to be having. It’s an especially great opportunity for me, following on these fabulous talks that have just happened, with their sort of engaged and thoughtful ideas about the details and the concerns that the Green New Deal brings up that frankly allows me to stay a bit in my comfort zone—and we’ll use this term quite a bit—in terms of trying to produce a set of sort of conceptual figures, right, that help us to think through some of these issues.

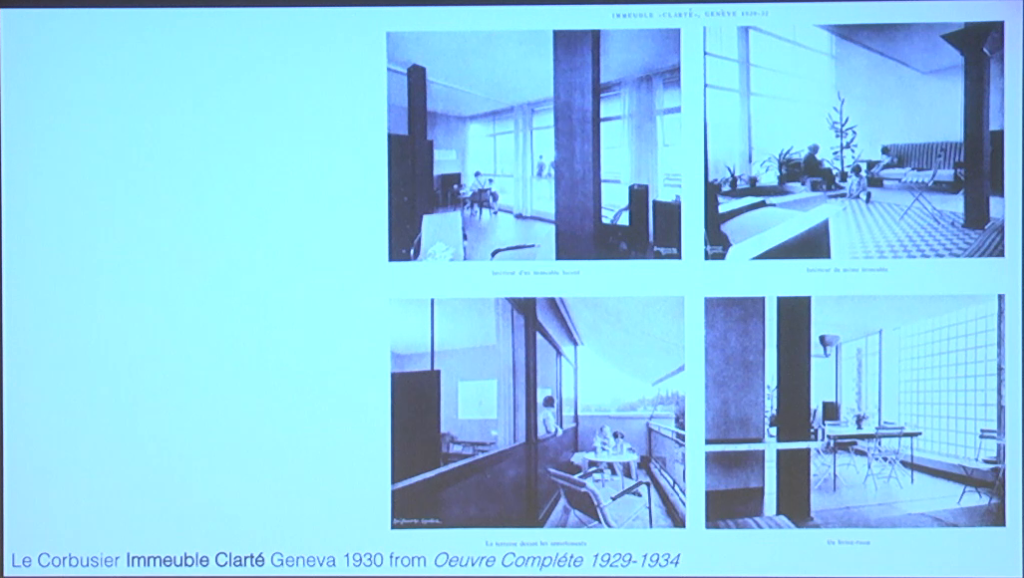

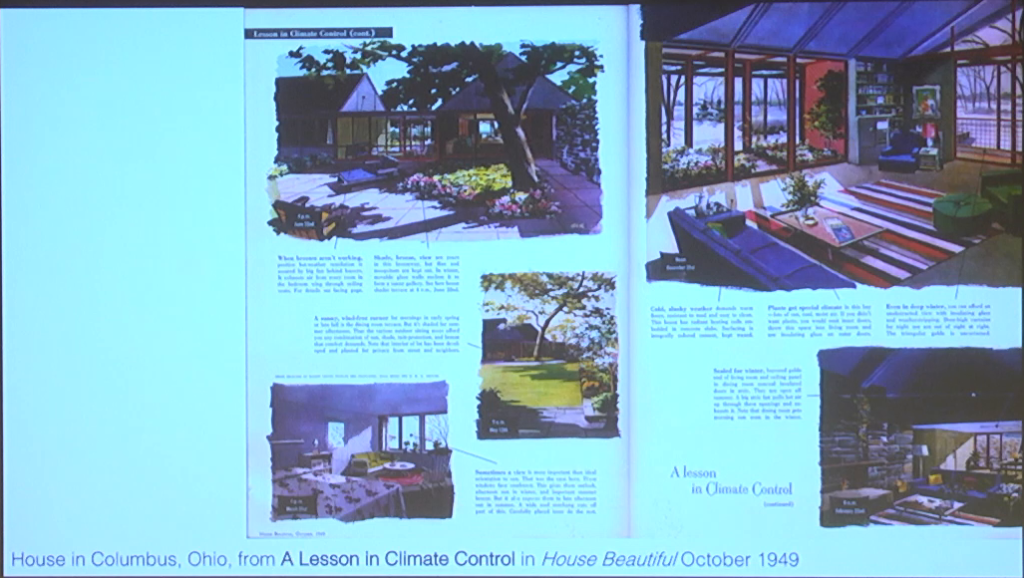

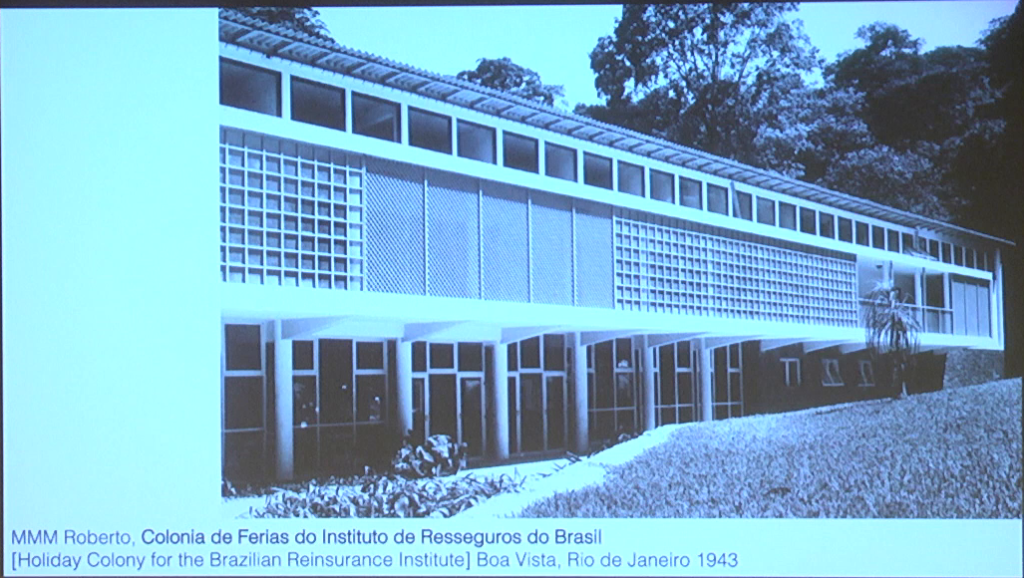

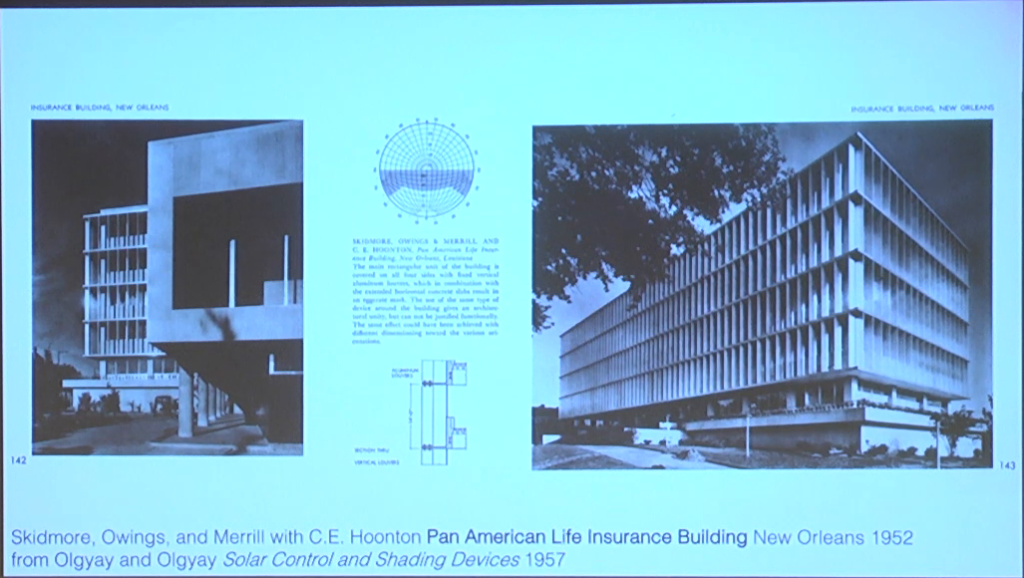

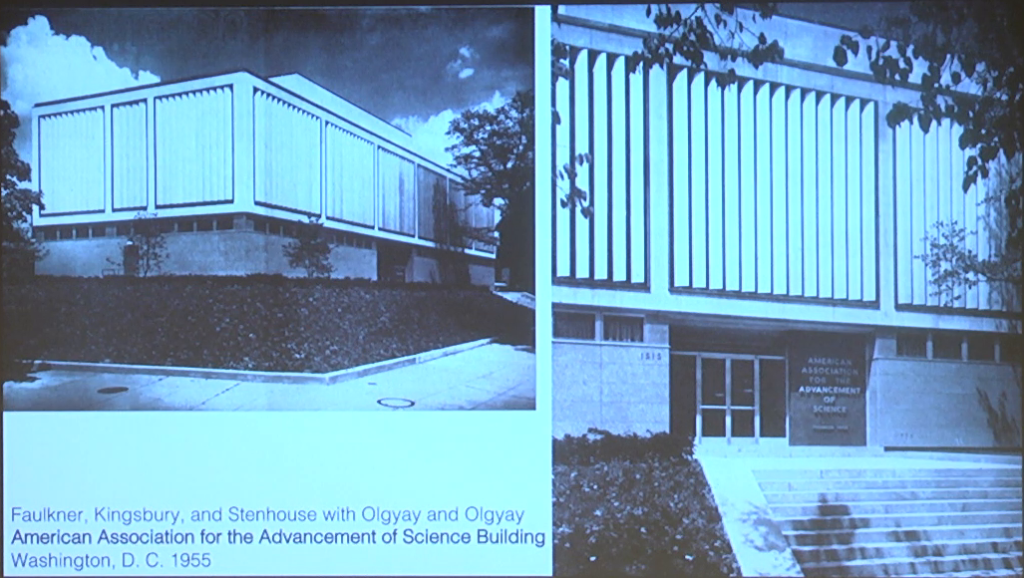

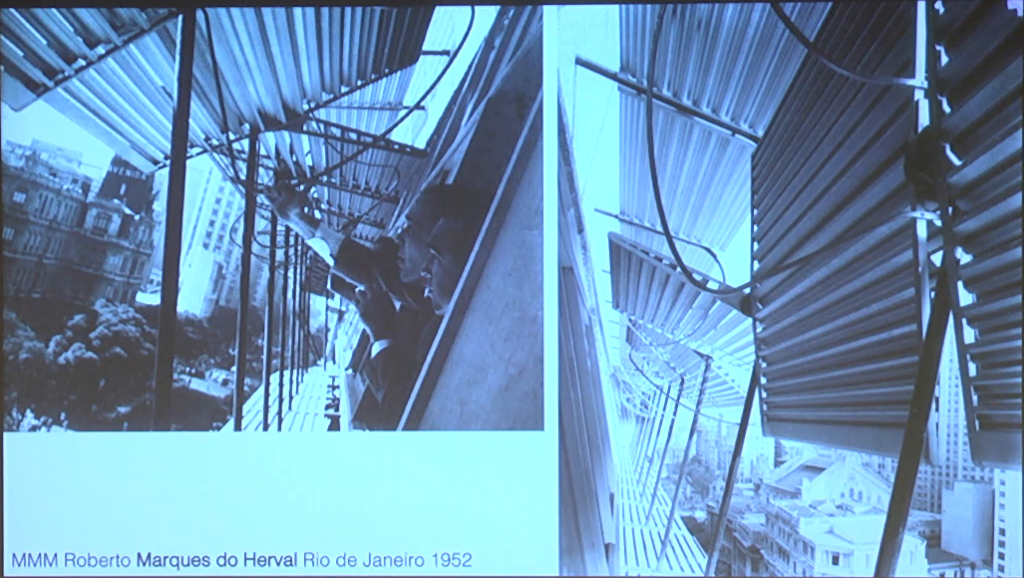

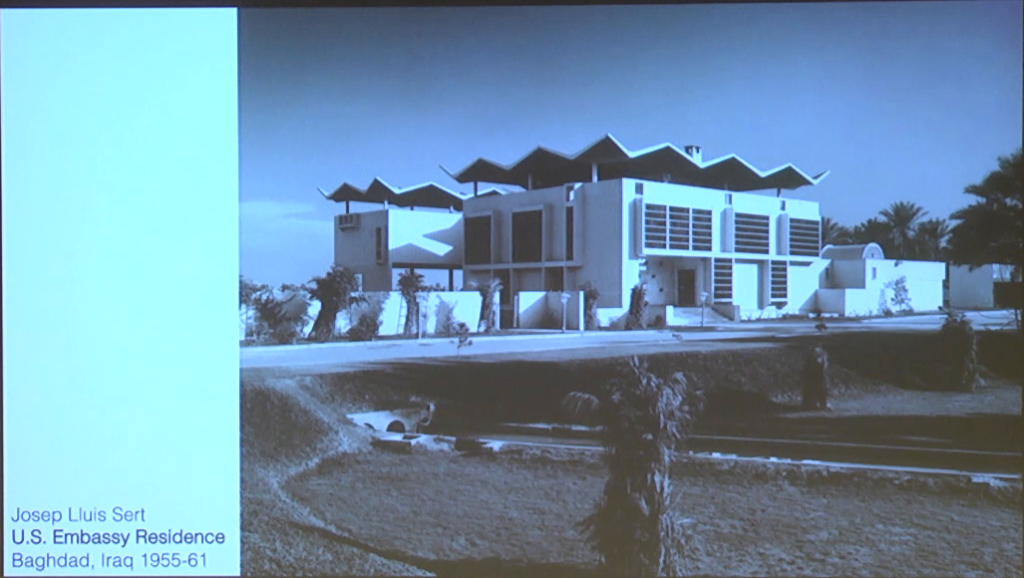

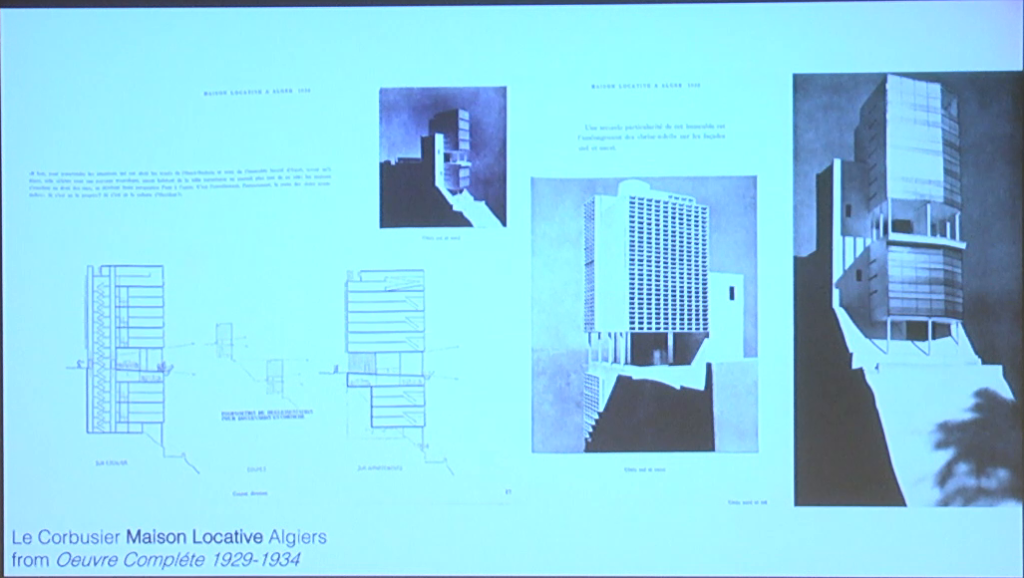

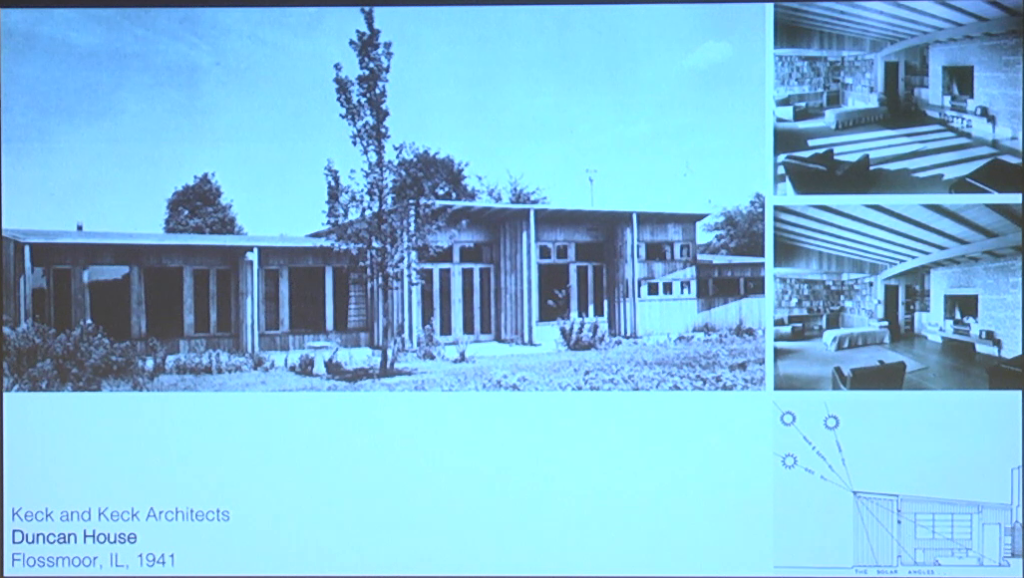

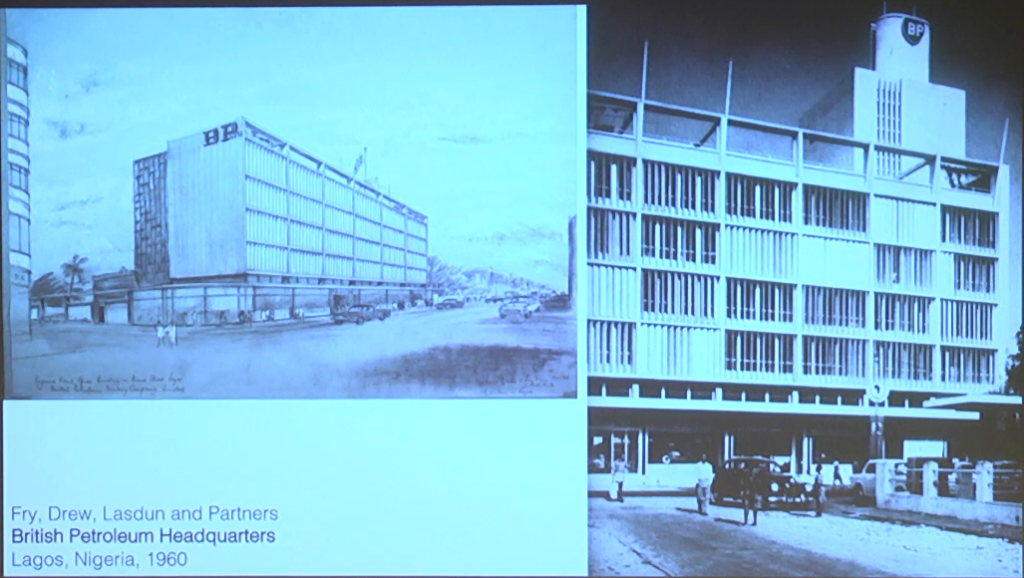

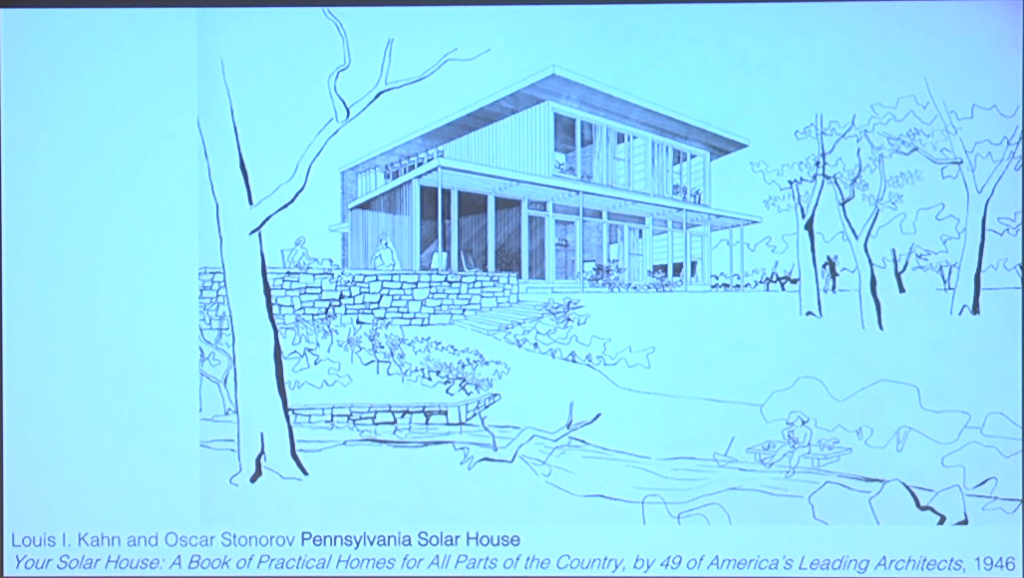

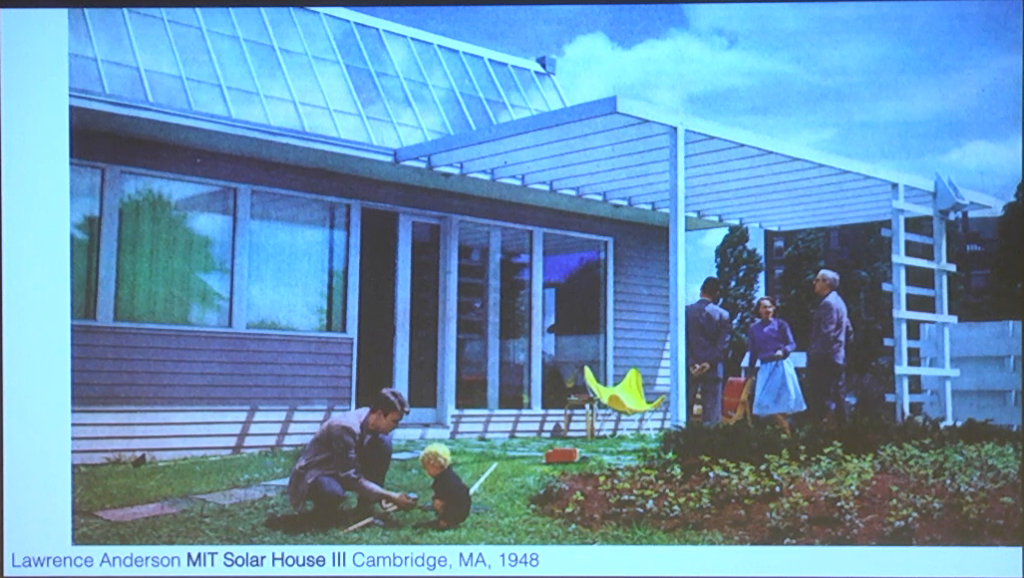

I’m an architectural historian operating as well in the environmental humanities, and my professional activities have two sort of main interrelated threats that are gonna play out today. One is to reveal and interpret an archive of architectural ideas, projects, and buildings that take advantage of their environmental situatedness in their conceptions of space, materials, and performance. Which is to say a sort of history of non-mechanical heating and cooling, right, of designing in relationship to the climate. The idea of that sort of thread of things is to demonstrate that environmental concerns have in fact been essential to architecture across its modern history and thereby sort of provide a different sense of possible future.

My second related professional focus is, to coin or sort of repeat a term that’s already been nicely played out this morning, to convince architects to give a damn about climate change, right. I actually had a different word in there but that’s okay. Depending on your familiarity with the field (I know people are here from a lot of different discussions) in the profession and in the schools this sort of ambition to get architects on board might either appear self-evident or totally absurd. The challenge that we face is that architecture has broadly speaking for the past few decades reveled in the production of formal virtuosity with little concern for its relational effects. Despite the facts that buildings and cities are of course an essential aspect of climate dynamics, the so-called mainstream of the field—and we could of course tease that out in much more careful ways—is just beginning to open up to the challenges that lay ahead—and Peggy also alluded to this a bit more precisely. Of course the Green New Deal offers some imperatives and instigations in this regard, as we’ll see play out in a minute.

So what I want to do today is to sort of play on both of these threads, right. I’m going to read some excerpts from a sort of manifesto I recently published titled After Comfort, which aims to identify comfort as an essential figure of thought, one that will serve as a passageway for the coming transition, right, a sort of initial foray in providing the field with some ideas about how to embrace the climate challenge.

Now I’ll just say briefly that this paper and the ideas around it comes out of a collaborative work I’m doing with Orit Halpern at the Speculative Life Cluster at Concordia University in Montreal. Orit and I have been framing this work through an initiative we’re calling the Institute For An Awesome Future, and that will be launching soon at the HKW in Berlin and then there’ll be opportunities for everyone to participate in this awesome future.

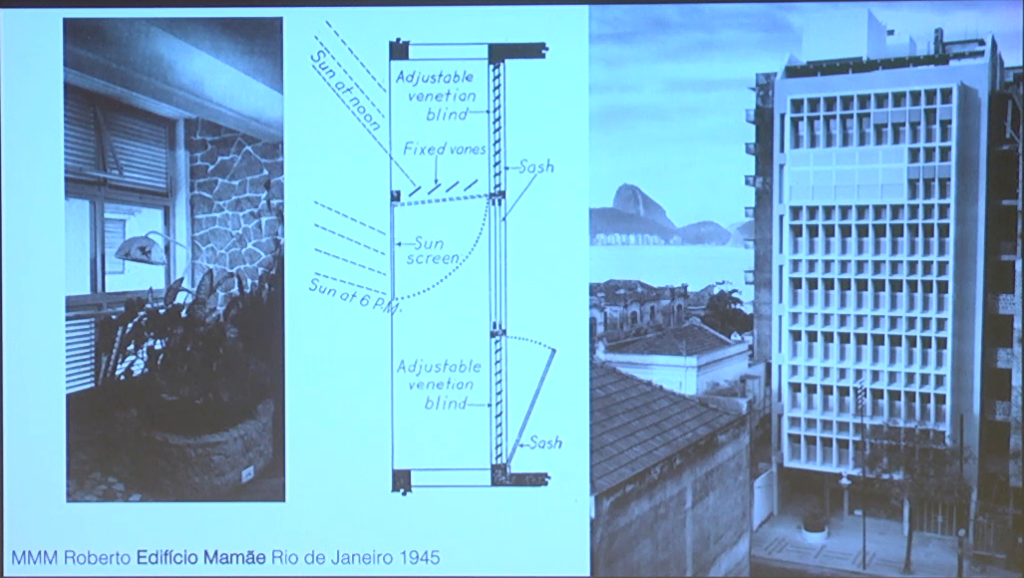

I’ll be reading a text and while reading it I’ll showing images of projects and buildings developed before widespread use of fossil-fueled air conditioning systems. So sort of indicating in this kind of before air conditioning and after comfort, the ways in which we’re sort of caught in the middle and looking somewhat desperately for a way out.

Okay, After Comfort.

The opposite of comfort is, obviously, discomfort. The first we seek, the second we try to avoid. Comfort is valued because it promises consistency, normalcy, and predictability, which allow for increased productivity or a good night’s sleep. Our collective allegiance to comfort is a form of self-assurance—that we are not threatened and that tomorrow will be like today. Comfort indicates that one has risen above the inconsistencies of the natural world and triumphed, not only over nature and the weather but over chance itself. We can rely on comfort. It will be there when we get back.

Comfort is integral to our designed interiors and to the causal chain that ties together heating, ventilation, and air conditioning—we’ll call it HVAC, right—that ties HVAC systems to the fuels that feed them, and to the carbon emissions that result. Comfort applies of course to many aspects of contemporary life, from the mega mansions of the suburbs to luxury upholstery in cars. In this general sense it’s tightly bound up with consumption. The thermal conditioning of interiors is of specific interest because it relates to the purview of architects, and because it is invisible and difficult to disrupt. Design is part of this causal chain, in other words, organizing and aestheticizing the connection between comfort and carbon.

Class distinctions are distinctions of comfort, both broad- and fine-grained. They are also economic and geopolitical distinctions. The West, the Global North, the geography of industrialized capital, the global territory of air-conditioning, politics in the 21st century revolves around access to comfort. The rungs of the ladder to luxury are physical, spatial, architectural, and thermal. First comes sustenance, then shelter and protection from the elements, then heat, and finally cooling, so as to remain active, healthy, and productive year-round. After these come layers of precision: filtered air, sealed membranes, sensors everywhere, all the elements of the comfort-industrial complex that aims to wrap itself around the body like a favorite shirt.

And I’m a bit disappointed we don’t have the kind of hum of the air conditioner in this room. But you know, usually usually it’s ever-present, right.

Comfort, like capital, is unevenly distributed—not everyone gets to have the same amount. When you have it, it’s hard to let go. It’s even harder to convince someone to give it up—and I think this is a major challenge we’re facing. Comfort feels normal, expected, obvious—deserved. To be rich means to never be uncomfortable. Unless by choice. The life of the poor, by contrast, is awash in discomfort, striving for relief. The struggle for comfort is a struggle for equity, justice, and conditions amenable to growth and self-actualization.

Comfort, however, is in short supply. Not because we are running out, but because we have to collectively adjust to its going away. Or rather, architects have to help make it go away. The scarcity of comfort is something architects can produce through a conscious redesign of the built environment. Since we can no longer emit carbon, right, we cannot be air-conditioned in the same way. Buildings must be conceptualized, designed, and built differently. We have to reconsider and renegotiate the terms of comfort and of productivity, equity, and equality.

It’s nearly impossible in the US today to design for discomfort. The cultural-industrial apparatus we frame as architecture does not interrogate comfort. The presence of HVAC is presumed, with few exceptions. It is invisible, hidden in drop ceilings, shafted behind walls and under floors. The duct, if you will, in the decorated shed.

This epochal aspect of building culture, essential to our near- and long-term future, is not readily available as an element of design or an object of discourse. Comfort is considered to be outside of architecture, the realm of consultants, despite the deep interiority of mechanical systems and the reliance in so many buildings on an impenetrable membrane.

And yet, the computational production of novel form (which is the phrase I use to kind of describe the architecture of the past thirty or forty years) relies ineluctably on mechanical conditioning. All of the architectural debates of the last five or six decades indeed relied on fossil fuels. Comfort has not recently been a subject for invention, imagination, and experimentation.

Every little click and hum of the air conditioner kicking in, every creak of the radiator, is a slow, extended, symphonic lament accompanying the decline of civilization. Comfort is destroying the future, one click and hum at a time, right. It’s kind of our task to recover it. Comfort relies on invisibility: you don’t see it, you pretend not to hear it, it’s just there, expected. Not only is the HVAC system hidden, so is the boiler, the fuel, the network of extraction, the labor exploitation, the carbon cost of distribution, the toxification of the air. Comfort yet is normal, in fact the epitome of the normative; regulated and rationalized, embedded in construction systems and industrial supply chains.

How can we design for discomfort and reveal these implicit structures of ventilation, of decarbonization? How can we frame livability, lifestyle, and life itself in the context of the geophysical and geopolitical implications of comfort? This is kind of the main point: Could it feel better to be uncomfortable? Perhaps there could be a pleasant sense of participation in a changed global-thermal regime.

We are no longer protected from the elements. The elements in fact are assailing us, determining our collective future. The experience of comfort inside is predicated on the global acceleration of climatic instability outside. We are exposing ourselves to the elements through our sealed, conditioned spaces.

The challenges of climate change are both political and physiological, among other things of course. How many will be discomforted, to what extent? Transforming personal and social expectations is one important element of this challenge, not the personal virtues of reduced carbon living—the sort of short showers thing, right—but the collective reframing of cultural values. Can we imagine, articulate, and proliferate a culture of discomfort? What would it look like? How does it feel? And, perhaps most importantly how do we get there? It’s a magnificent challenge for architects who, as a profession, are so inextricably entangled in capital, yet licensed to imagine. Design for discomfort is an opportunity, a growth industry.

The built environment of course is contingent. It was constructed according to specific socioeconomic conditions, collective desires, and cultural interests. It can be rebuilt according to new conditions, new desires, and new frameworks for cultural elaboration. Such reconstructions also reimagine relationships to resources, economies, form of exchange, and conditions of equity. Architecture’s new ambition, I would propose, is to condition humans to be less comfortable.

So it’s in part also to recognize the extent to which “air conditioning” as we’ve come to know it is of course also people conditioning, right. We’ve kind of adjusted ourselves to these specific carbon-heavy conditions.

A first step: retrofit. House Resolution 109 calls for upgrading all existing buildings in the United States to achieve maximum energy efficiency.

The Green New Deal reaches out towards this sort of disciplinary transformation. It might hurt initially for some of us here to think of architecture’s role as simply “upgrading,” right. Yet it reveals burning questions: What new construction can be justified? If it is really all about carbon, what is left for architects to do?

The savvy design collective of the near future sees opportunity in designing for discomfort. In careful retrofits that reduce comfort, reduce carbon, offer new ways of living. Through collaborations with physiologists, engineers, artists, and others, design methods can not only reduce reliance on mechanical conditioning, they can also be compensatory, creative, and instructive. The experience of a room or a city can encourage and reward the lifestyle, habits, clothing, and activities that reduce comfort.

This transformation is profoundly cultural. It resists sustainability metrics and exceeds performance softwares. It focuses instead on the contours of our desires and our values. This again is the role of architecture, even or perhaps especially in retrofits. To make discomfort desirable. To help us all find pleasure in a new causal chain, one that starts with the less-conditioned interior, extends to the less carbon-filled atmosphere, and resolves itself by tempering the inequity, exploitation, and destruction that increases with climate instability. Discomfort, that’s to say, is not a bad thing. We will be discomforted either by design or by default.

The architecture of discomfort will be multifaceted. The glory of architecture of course is that it revels in its own creativity, in the pleasant unfamiliarity of affective space. It provides something new. Yet the terms of this novelty have been too tightly proscribed. Unleashing architects to design for discomfort will produce spaces, materials, and systems wholly unimaginable in the present. We anxiously await this explosion of carbon creativity. Thank you.

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page