Agriculture has transformed the planet. We use more than a third of the Earth’s surface to grow crops and raise livestock. About 70% of global water withdrawals are for agriculture, and our food systems are implicated in up to a third of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Each of these dimensions of global agriculture is now being influenced by globalization.

Consider the meal pictured here. Depending on where in the world you live, the ingredients may have been sourced from very far away, including feed crops such as soy used to produce the meat. In many countries, the very ability to eat a food like avocado is a direct benefit of international trade. We are eating on an interconnected planet. Food trade now shapes land use worldwide and is reshaping the food supplies of many nations.

With this agricultural globalization, food production and consumption are decoupled, making it more difficult to see cause and effect between our diets and the agricultural landscapes on which we depend. Growing global demand for certain commodities is now intertwined with local issues such as water scarcity, pollution, and deforestation.

Photo: Flickr

In particular, commodity crops such as palm oil and soy have transformed land use in a few key countries where global production’s now increasingly concentrated. What are the broader implications of this globalization in our food system in terms of food security and resource sustainability? My lab at McGill University addresses this question by combining global data on trade and food supply statistics, with different types of agricultural land use management data.

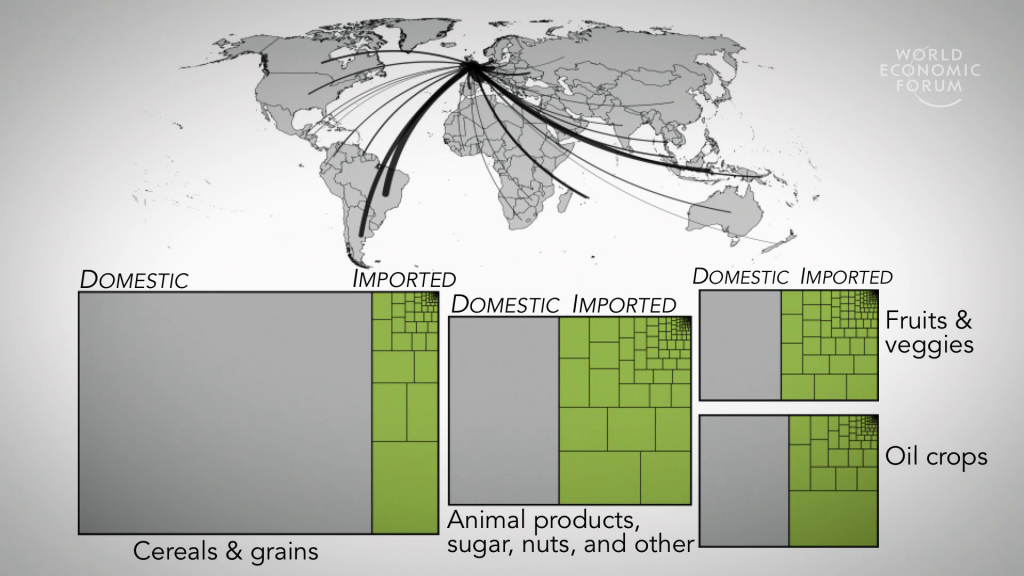

An illustration of this food systems globalization is shown in this map here, which shows a network map depicting the global reach of the United Kingdom’s calorie supply from imported agricultural commodities. The boxes on the bottom show a more detailed breakdown, comparing each trade flow with domestic production of different commodities. Britain’s particularly globalized diet links it with a diversity of farming systems and climates around the world.

We’re also studying these calorie import networks over time. These graphs compare the sources of Japan’s calorie imports, which are concentrated and remain very stable over approximately two decades, to Saudi Arabia’s which a much more dispersed across many countries and change dramatically over this time period.

The structure and composition of these food import networks moderates linkages between countries in terms of food and resources. By combining these global trade data with data on crop yields, fertilizer use, and water use, we can investigate how trade impacts the distribution of resource use across countries.

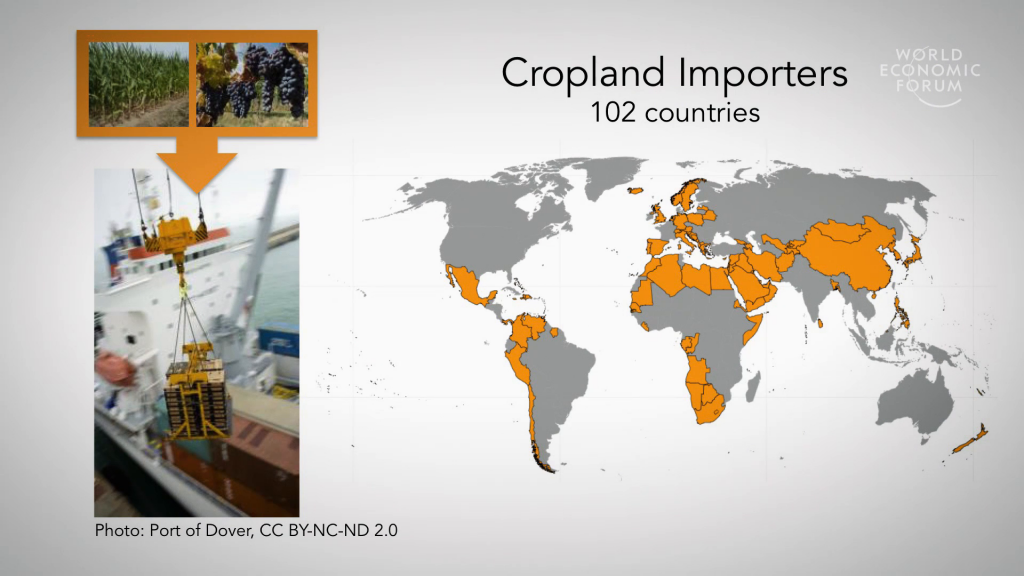

What we are finding is that some countries are becoming increasingly reliant on foreign sources of land use underlying their food consumption outsourcing. With this, hundreds of millions of people are becoming reliant on potentially less-certain sources of food and the resources needed to grow it.

This trend is facilitated by other countries becoming more export-oriented in terms of their land use. Many of the countries pictured here in dark green use more of their domestic croplands for export production than for their own domestic food consumption. Other countries are even more highly globalized, essentially exchanging their export commodities for foreign imports grown on land use abroad.

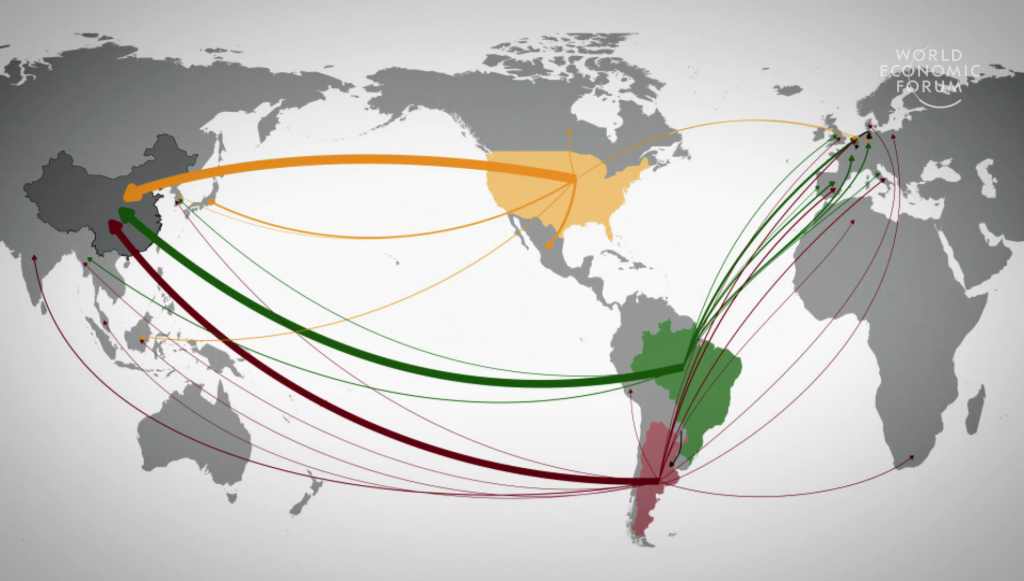

A shift toward specialization and concentration with globalization has fueled the emergence of disproportionately large and land-intensive trade relationships, such as pictured here for the global soy trade network. Just three countries produce and export about 80% of soy globally.

Agricultural trade such as this can help to promote gains in average resource use efficiency in agriculture, reducing the amount of land, fertilizer, and water required to produce food calories on a global scale. However, the diversity of agricultural systems from which these imported foods are sourced means that these efficiency gains are not universal, and may not occur for the same foods in the same countries.

As food consumers, we’re also increasingly urban. This compounds the challenges of globalization in separating us from food production landscapes. Our next step is to look at these global data through the lens of more local case studies, to ask where globalization is beneficial and where instead we might strive from a middle ground model of regionalization.

Part of navigating this is remembering that global food trade is not just about economics. In studying agricultural globalization, I’ve been learning that we can get a very different understanding of the structure and composition of global food trade networks using monetary, nutritional, or resource-based metrics.

In the next few decades, it’s projected that demand for food globally could increase by 60% or more, likely driving even greater separation of food production and consumption. In this time of change, we should envision what sustainable local and global food systems look like. How best can we all benefit from the diversity of agriculture on our planet in a fair, sustainable, and food-secure way? Thank you.

Further Reference

Annual Meeting of the New Champions 2016 at the World Economic Forum site