Okay, so enter 1983. I don’t know what you were doing at this period of time, but a lot of things happened. The first mobile phones, compact discs, Michael Jackson, WarGames…a lot of things, depending on your interest.

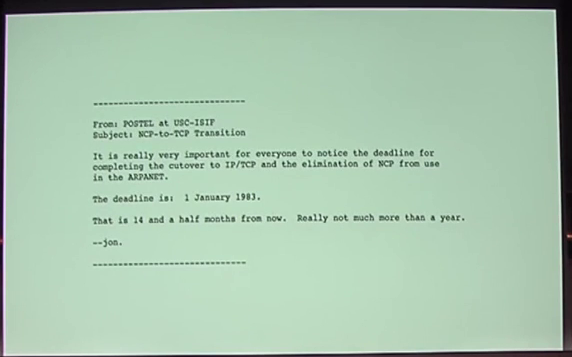

In my case [modem connection sound starts playing] I think it was something which was not glamorous, not tangible, not even visible, something happened that kind of changed the way we were dealing with everyday life. And it’s the shift that happened from the NCP protocol to the Internet Protocol suite. The network design was open enough to connect potentially every computer worldwide, and it became the most widely-used network, and we’re still using it today. [modem sounds end]

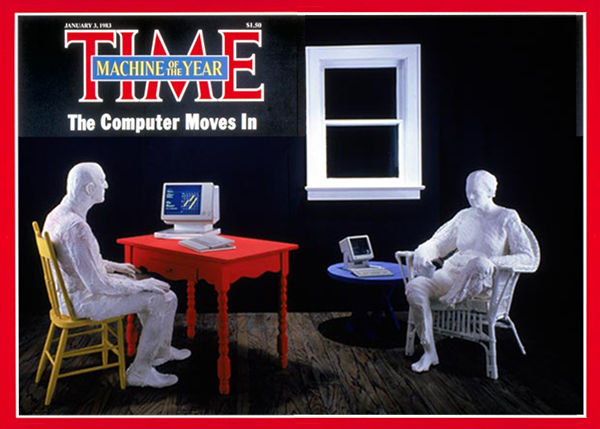

I’m not interested in the technical aspect of this innovation. What interests me is how people at some time, at some point, made it visible somehow. This cover of Time (You can see we like Time magazine.) is [expresses] a lot of the kind of tension and the mixed feelings about the coming of technology in the household. The face to face of these characters, they don’t know exactly how to communicate. They don’t know what to do with this new non-human agent that came into their life. And it looks a little bit like they are waiting for a signal, something that can help them to communicate. It’s a little bit the calm before the storm. And there is one detail which is quite striking. It’s the window, which commonly is the opening to the world. The window is black, and the reality is seen on screen.

Image via Wikipedia

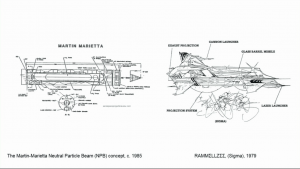

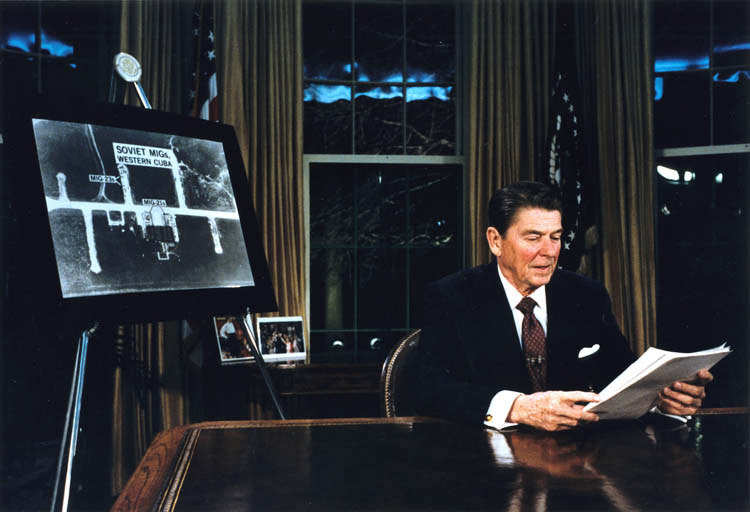

At the same time, by coincidence, President Reagan launched a new era in space exploration with the development of the program called Strategy Defense Initiative. The idea was to make a satellite-regulated shield that could automatically dismantle nuclear projectiles. This was a very big shift in the way the United States were dealing with space exploration. And the program, very expensive, was dubbed “Star Wars” by its critics.

I’m not going to deal in this political agenda, which was quite complex. What interests me is the way they used visuals, especially computer graphics animation, to provide legitimacy to the project. Suddenly, this kind of imagery, which used to be used in films like Tron or was common in video games, was used in foreign policy speech and suddenly gave strong credibility to this kind of imagery. Computer graphics imagery almost became objective tools like photographs used to be from the invention of photography.

This links to another kind of imagery which is quite interesting. All the renderings, the diagrams, and the images that were produced during this time and for this project had dimension, artist concept, artist vision, artist rendering. Sometimes they were even signed. And it gave a serious scientific authority to the artists.

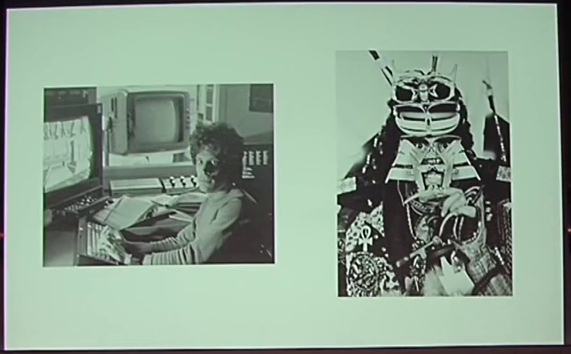

So that’s a little bit how I came to go in this direction. I was interested in the way artists in this specific context translated this historic moment in their productions. I decided to focus on two very seemingly-opposite artists. One is David Em on the left. He lives and works in Los Angeles. He began making sculpture, film, photography, and printmaking before becoming one of the pioneers of digital art. During the 70s and 80s, he worked at Xerox PARC and JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory), the place where the Star Wars program was elaborated.

On the right is Rammellzee, a visual artist, musician, performer, poet, born in New York in 1960. In the 80s, he was part of the first generation of graffiti artists to get worldwide recognition. They seem to belong to totally different worlds, and the idea of this presentation is a little bit to see how they are not so different.

David Em, “Escher” 1979

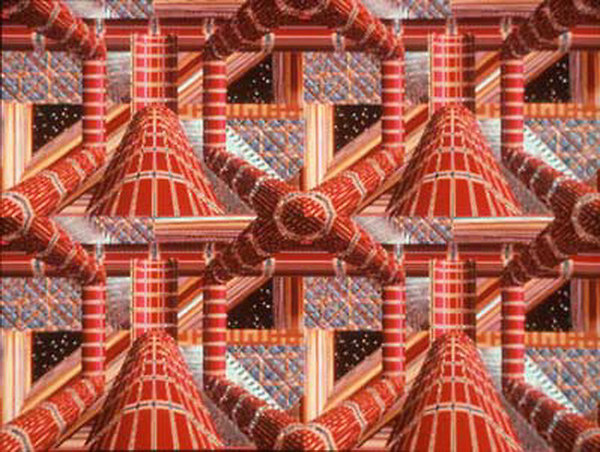

Coming back to the work of David Em. He worked during the 70s at JPL, a branch of NASA which was specialized in space exploration. By chance, he didn’t have to work for the Army, but he had access to the state of the art in computer graphic software. He worked with masters in computer graphics like James Blinn, whose software helped him to develop his own style.

He also liked to make the link between his former sculpture practice and what he called the virtual world. He liked computer graphics because it allowed allowed [him to stretch the canvas, to open hybrid territories that are located outside the traditional art networks. He was very popular among the public.

One of his most iconic images is called “Approach,” and it referred to this very iconic image we saw back in the 60s, or that were produced back in the 60s, showing this little Earth in the middle of the universe. This image polarized opinion, because it has a strange poetic feeling. It kind of shows the global penetration of technology. And it looks a little bit like a planet which is seen through the lens of a machinic vision.

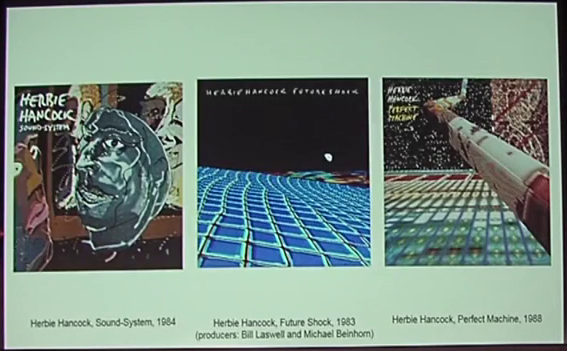

If you’ve seen this photograph before, it might be on the cover of the album Future Shock. Herbie Hancock produced this album, a series of three albums actually. All of them have David Em artworks on the cover, and Future Shock was the most successful album. The image went viral. The title is borrowed from a book Alvin Toffler wrote in 1970 which was quite influential. And most of the project is dealing with the idea or the concept of information overload that is part of the main hypothesis of Toffler in his book.

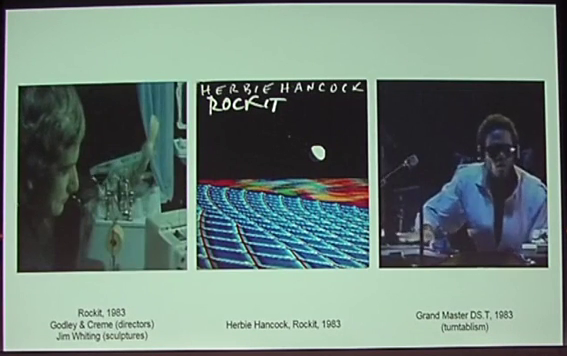

What is interesting in the big success of this collaboration between Bill Laswell and Herbie Hancock was the single “Rockit.” I don’t know if you remember it, but back in 1983 you had this very strange video, and this very unusual noise, which is the noise of Grandmaster DST scratching, appropriating the turntable and making sounds that were not very common on a record at this period. The video is also this very strange and creepy flat where these robots are kind of making staccatos following the rhythm of the track. This was a very strong image that kind of also opened some new sonic territories, I would say.

“collision music” involves seemingly disparate elements being thrown together in an attempt to create new sound.

John Doran, “Bill Laswell Interviewed: Bass. How Low Can You Go?”

Regarding the concept which was behind the project, Bill Laswell liked to talk about “collision music,” the idea of bringing different elements together and opening some new sound or new ways to listen to music. This concept of collision is really at the core of the work of Rammellzee. So I’m going to go a little bit further describing his universe.

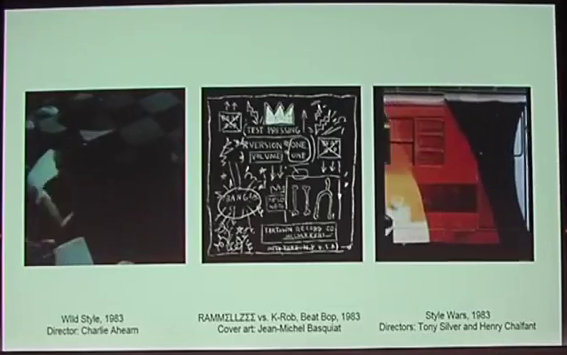

Rammellzee had a very big time in 1983. He did a collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat on a single called “Beat Bop,” and this was a very successful record which is always one of the most sought-after rap records. He also played in a film called Wild Style, and another film about graffiti art that is called Style Wars. That was the moment where the hip-hop movement broke into the mainstream and the world was just discovering youth culture, which was using old technologies inherited from the industrial era, like highways and the train system, as a new means of communication.

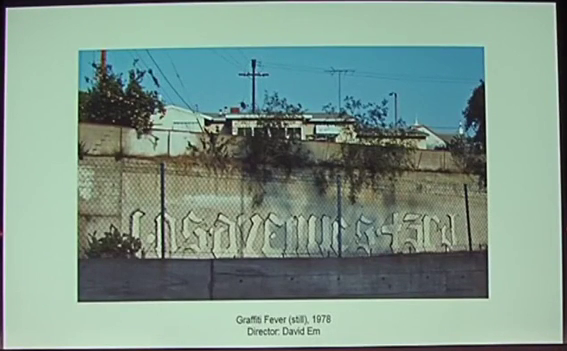

And that’s when Wild Style and the universe of Rammellzee and the universe of David Em are coming together. David Em was very impressed by the graffiti he saw in the cities of Philadelphia and Los Angeles back in the 70s. He was really impressed by the aesthetic of this graffiti, but also by the freedom that these youth got to make their art. He was so into it that he started to photograph and collect different inscriptions and made a documentary in 1978 called Graffiti Fever, which is about the emergence of the street art movement. It’s one of the first graffiti documentaries, and it kind of made a very strange connection between the early experimentation in computer art and this youth movement that was completely vernacular somehow.

David Em, that I interviewed recently, was mentioning this moment saying that back in the mid-70s when he saw these inscriptions, it kind of pushed him to define his own style as a digital artist. And this is an interesting connection, I think.

![Ionic Treatise Gothic Futurism Assassin Knowledges of the Remanipulated Square Point's One to 720˚ to 1440˚ The RAMM-∑ LL-Z ∑∑ [Wayback Machine]](http://opentranscripts.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/joel-vacheron-1983-blackened-window-024.png)

Ionic Treatise Gothic Futurism Assassin Knowledges of the Remanipulated Square Point’s One to 720˚ to 1440˚ The RAMM-∑ LL-Z ∑∑ [Wayback Machine]

Going back to the work of Rammellzee, he also saw a very special way to deal with graffiti. His trick was to kind of make some connection and add some technical concept to his writing. He considered graffiti as viruses. And what he liked to do was to connect his production to military language. He was saying that the graffiti artists were in a kind of symbolic campaign against the standardization of the alphabet. He liked to create idiosyncratic languages and was kind of mimicking the language of the Army. On the right, you can see these letters morphing into rockets. All this kind of esoteric theory, he called it “gothic futurism.”

Sometimes one can find some strange examples where his drawings are almost the same as the drawings made by the weapons manufacturers at the time. So here on the right you can see the letter sigma morphing into a rocket, for example. And on the left it’s an original rendering of the SDI made in the mid-80s. Somehow he was kind of hacking the military language and the language that was used for the rendering of the Star Wars products or development.

Images via Beautiful/Decay, “RAMMELLZEE’s Singular Visual Stylings”

He also used to work in 3D, somehow. Like making these sculptures from waste material that he found in the streets. He called them “Letter Racers” and they were made from pieces of wood merged with dislocated dolls, skateboard elements, and other toys. That was an interesting precursor I think of the way we use 3D printing nowadays. And these letter [racers] for example are kind of all based on a letter, which is kind of difficult to read, but he had definitely something that was linked to the letters and the language.

Image via Radical Presence

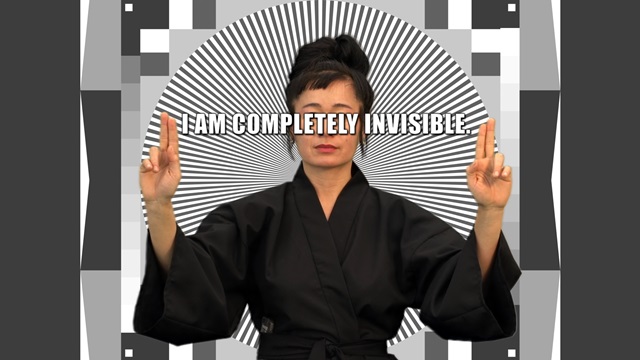

Another thing that he liked to do was to stay anonymous. He hardly ever appeared in public without a costume or a mask. He kind of created a lot of avatars that were inextricable from his work, and he liked to role play and discuss the idea of identities. Somehow he prefigures the way we’re dealing with avatars in social networks. I would say that he is a figure of the hacker.

Technology has taken us by surprised, and the regions that it has opened up are glaringly empty.

Siegfried Kracauer, Kreise und Tanz, 1925

I like this sentence from Kracauer that I think still works nowadays. These examples, David Em on his side, Rammellzee on the other, what they brought us is a kind of vision that helps us to foresee a little bit what technology could bring us. They are somehow the aliens of these new territories.

Alex Czech, “3D Printed Exoskeleton Arms”

Regarding what we could say about this inheritance, I think the idea of 3D printing and the way we are dealing with body enhancement, for example, are good examples of what Rammellzee was doing in a very DIY way.

There are also artists that are dealing with the language, for example Constant Dullaart with his project DullTech, who is mimicking a little bit the world of the startup, making what he calls dull technologies. And also we kind of find this division in the way Rammellzee was dealing with the DIY ethos.

I was thinking also of Hito Steyerl, in a movie dealing with mass surveillance and the way the contemporary visual regime is more and more militarized.

There are also some examples in music, and I wanted to finish with this quote that comes from Cybotron. Enter is one of the first techno albums.

Enter the new round

Enter the next phase

Enter the program

Technofy your mind

Cybotron, “Enter”, 1983

Thank you.

Nicolas Nova: Thanks, Joël. We have quite some time for questions, so let’s talk more about these things. One of the projects you mentioned, wa a series of projects, is by David Em. If I remember well, David Em used to work with companies like Xerox PARC, for instanced. To clarify the context, how would you define his work, thinking about what you showed, what’s the role of this in Xerox PARC at the time?

Joël Vacheron: I don’t know much about David Em because I discovered him working on this talk. But I’ve been very impressed [with] the way he was having his own way of dealing with digital art. There’s a documentary that you can see on YouTube that explains his vision a bit, and it sounds so contemporary like, you have the impression that it’s a post-Internet artist somehow. And I think at the time, he had a lot of freedom to experiment and go the way he wanted to go. But for that, he needed a strong vision and I think he got it.

Nova: Did he do that as a side-job, compared to what he was used to do there, or…?

Vacheron: I have the impression that he was pretty full-time, but I’m in discussion with him. That’s the kind of question I might ask him.

Nova: What is also interesting with Rammellzee, the artist who did the masks and the machines out of discarded objects is that this looks very contemporary, as you said. And it seems like if you look at the word of some artists now, working with a critique against mass surveillance or cameras, there’s a very interesting echo. But of course it’s different because it was in the 80s. So what do you think made Rammellzee anticipate that? Was he interested or focused on thinking about some sort of sci-fi dystopian world, or was he interested in some sort of repurposing of existing technologies?

Vacheron: I think he was already a kind of maverick. And he had a lot of humor, and he must have had fun because he died in 2010. But I figure he had fun making these little game role-plays. And he was also part of this tradition that we could call Afrofuturism, which is… We know like Sun Ra back in the 50s, 60s, already starting from the sound of the Moog, the first Moog sound, like electric Moog, started to develop a rhetoric about space travel and all these things. So he kind of also had a heritage or tradition in which he could easily go.

Nova: One of the reasons why I was interested in this 1983 topic is that a lot of the examples that Joël has showed anticipate the world of today. But I’m curious what happens when you teach at the academy. You have students who were born after 1983. What happens when you show them these kinds of examples? Does that make sense for them, or is it surprising? What kind of debate does that lead to?

Vacheron: I think it’s interesting because this example especially, regarding digital arts kind of lot it credit, somehow, back in the 90s and early 2000s. And it comes back. And I’m always surprised to see the students, the new generation even younger than…people born in 1983, really like this kind of approach. And I think what they like is the fact that it’s strong vision, and people really believed in what they wanted to do and didn’t care about any people who don’t Like when they post something on Facebook. I don’t know. I think for them it’s a very encouraging sign that there’s possibility to do things that last.

Nova: One of the messages here is that if you look at artists’ work at that time, for instance, that anticipates trends in terms of culture and technologies. But that was 1983. Can you give us some examples of artists from today who not necessarily might be the next Rammellzee, but who might tell us something about the future of technologies?

Vacheron: I think the quote of Cybotron is quite interesting because this is officially the beginning of the techno movement, 1983. Juan Atkins is part of this first generation of techno producers, but he’s still present. And if you listen to techno music, it has changed of course, but it’s still the same somehow. And the same with rap music, which kind of broke out back in 1983 or early 80s. So I think there are things that last and we still hear them as original.

Nova: But are there new ones in visual arts, or in other types of arts nowadays that would be inspiring for you as a way to think about the future?

Vacheron: Yeah, Hito Steyerl, Constant Dullaart, and I would say Kim Laughton, for example, and artists that are so recently…who does a lot of things based in Shanghai that kind of provide a really interesting vision of how the world could [look] when most of the cultural example elements would be Asian or Chinese.

Nova: Thank you very much, Joël.

Vacheron: You’re welcome.

Further Reference

Bio page for Joël and session description at the Lift Conference web site.