Hi, everyone. Glad to be back.

23andMe is a US-based company that will, for a fee, analyze your genetic ancestry. Provide some saliva, and they’ll send you a summary that compares your DNA with thirty-one identified populations across the world. It seems that this sort of genetic analysis is the next big thing in family history, and you may have noticed that Ancestry offers a similar service. 23andMe, however, also provides an application programming interface, an API, so that developers can create cool third-party apps with your DNA. Don’t worry, you do actually have to provide permission. So Facebook won’t automatically start sending you friend requests based on your genes. At least not yet.

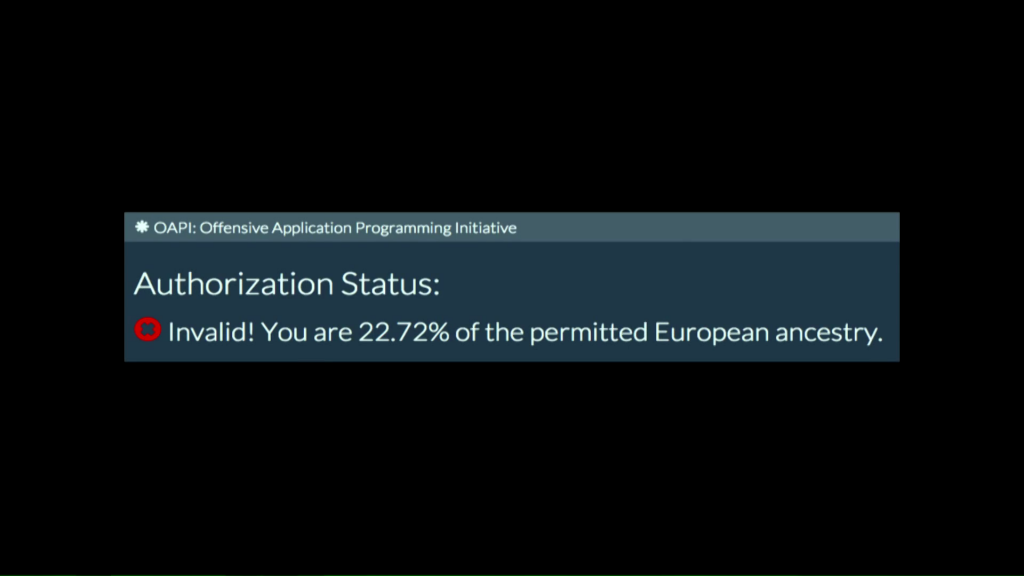

But it didn’t take long for the ethical boundaries of this sort of service to be tested. One developer created a genetic access control authentication system. Using it, online sites or services could restrict access to people who had a specific genetic makeup. This was an actual example from the guy who developed it:

The developer’s API access was quickly revoked, with 23andMe noting that their Terms of Use prohibit applications that contain, display, or promote hate.

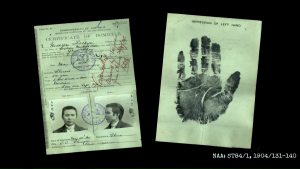

Four years ago, I stood on this stage describing a project that I was working on with Kate Bagnall called Invisible Australians. We were and are trying to encourage use of the National Archive of Australia’s collection of records that document the workings of the White Australia Policy in quite confronting detail.

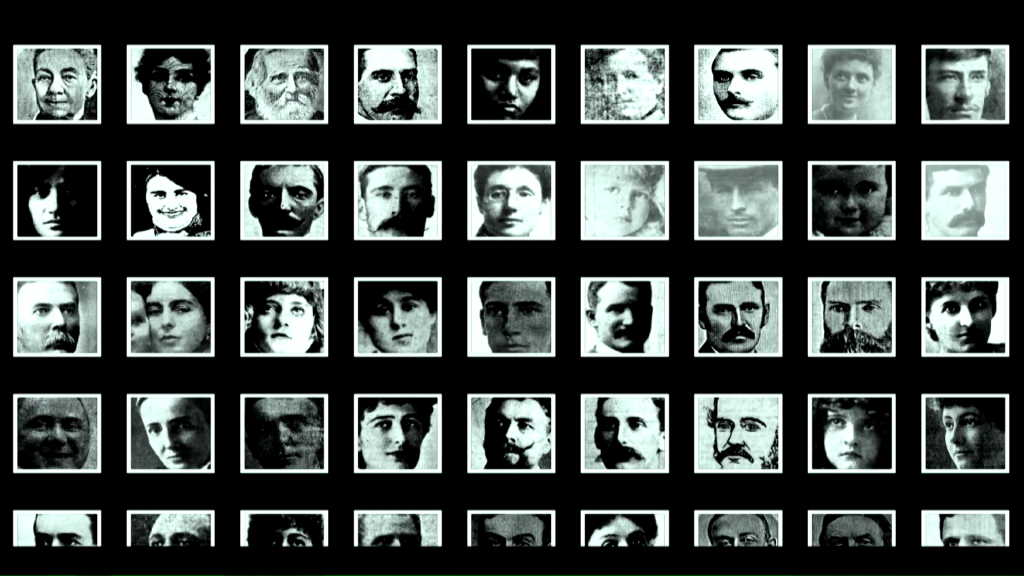

As an experiment, I downloaded thousands of images from the Archive’s collection database. Most were certificates used in the control of non-white immigration, visually compelling documents that include both portrait photographs and handprints.

I ran a facial detection script over these images to extract the portraits, and created an online resource called The Real Face of White Australia

For a weekend project, it’s had a significant impact in the digital humanities world. Some people criticize this, though, because they thought we were actually selecting records based on race. This was just a misunderstanding of both the records and the technology that we were using. Even if I’d wanted to, I wouldn’t have had a clue back then about how I would categorize these portraits by race.

Now I do.

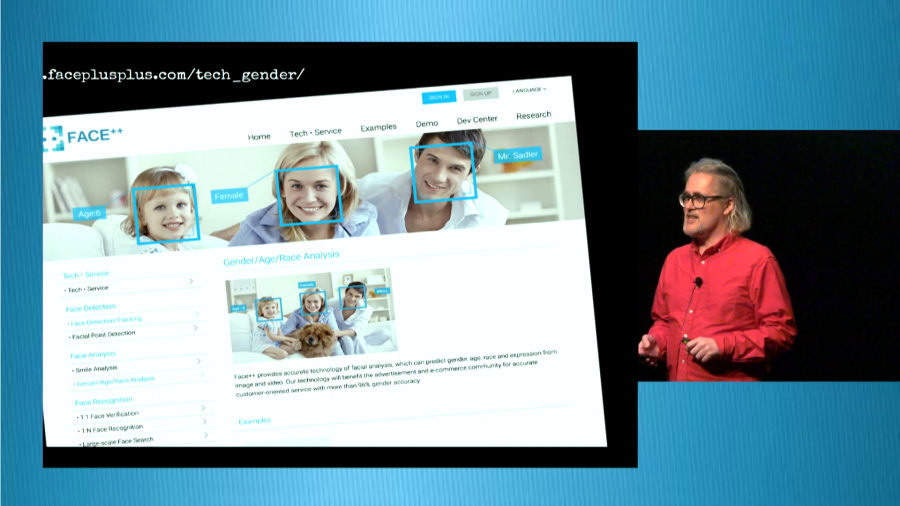

I can sign up for an account with a service like Face++ and use their API to analyze an image of a person’s face to determine both race and gender. After a bit of a break, because of life, Kate and I are getting back to Invisible Australians. In 2011, I had about 12,000 images from one series in the National Archives. I’ve now hosted more than 160,000 images from twenty-two different series.

But the intervening years have also brought changes in the Australian government’s treatment of asylum seekers. It’s brought changes in greater power for security agencies and the normalization of electronic surveillance. When the White Australia Policy was implemented, portrait photographs and fingerprints were the latest in crime-fighting technology. Just over a month ago, the Australian government announced its newest national security weapon, a national facial recognition system to be known henceforth as The Capability.

It’s true, it’s true. I suspect they already have the movie rights in mind.

The system would assist authorities in putting a name to the face of terror suspects, murderers, and robbers. Tools that help identify faces can offer powerful new means of discovery and analysis within the holdings of our cultural collections. But can those of us who work with these tools avoid engaging with broader systems of surveillance, categorization, and control? For Kate and me, the parallels are just too strong. History is not just about the past.

I’m talking today about two related technologies, facial detection, and facial recognition. Facial detection simply tells you if there’s a face in an image. It’s a the technology that draws little boxes around faces when you’re taking photos, and it’s pretty efficient and well-established. This was the technology that I used to create our wall of faces.

Basic detection is now being supplemented by algorithms that examine the shape of facial features, and the characteristics of things like skin so that they can estimate gender, age, and race. They can also tell you whether the person is wearing glasses, and the quality of their smile.

- Here’s a winner.

- Here’s a loser.

Facial recognition, on the other hand, first detects faces within an image, and then searches for those faces within an existing set of previously-identified images. The Capability, for example, plans to take an image and look for matches across a series of interlinked databases such as passports and driving licenses. It’s also of course what Facebook does when it tags people in the photos that you share.

Facial recognition is a lot trickier than detection, but last year Facebook announced that its DeepFace system (Don’t you love all these names?) had reached a level of accuracy similar to humans. Not to be outdone of course, Google claimed it’s FaceNet technology had pushed the bar even higher, reporting an accuracy of over 99%. How this translates to real-world applications such as The Capability is not clear, but I think we can safely assume that the security agencies are heading down the same path.

Machines have struggled to match humans in finding and recognizing faces because faces are so important in simply being human. Faces connect us to our social world. But as cultural institutions know, faces can also connect us through time. Looking into the eyes of a person, no matter how far removed through time, history, or culture, affects us. We do not merely see, we feel. And this I think is where The Real Face of White Australia gains its emotional power.

Last year, in another experiment, I started extracting faces from Trove’s millions of digitized newspaper articles. The images are of a much lower quality than the photographs of course, but still…there’s that feeling of connection.

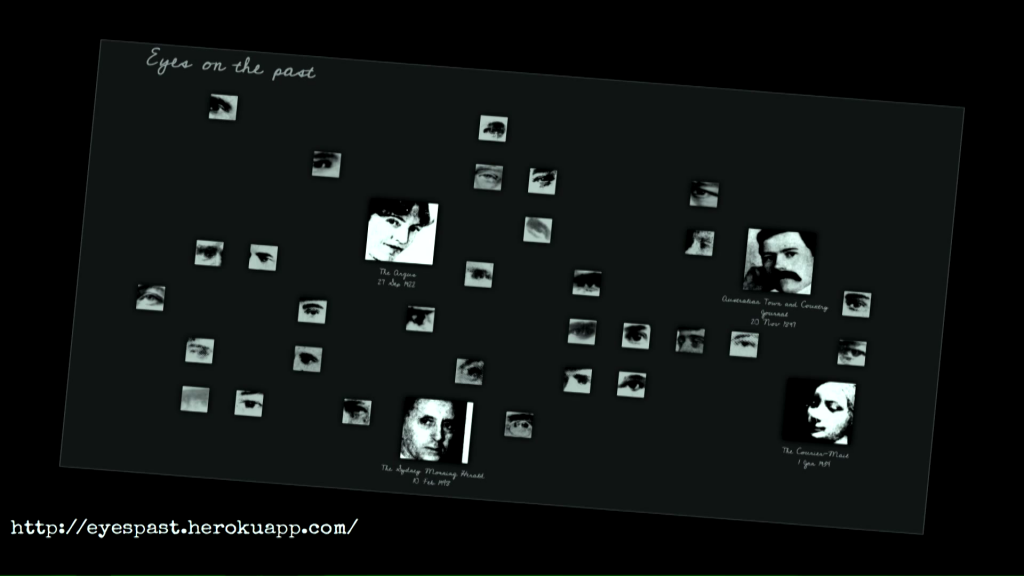

Facial detection is one example of a broader class of computer vision operations known as “feature detection.” You can train your computer to find all manner of patterns and shapes in your images. This includes things like cats and bananas, as well as the components of the face, eyes, nose, and mouth. So of course, one night I wondered what would a newspaper discovery interface based on eyes look like?

Eyes on the past has been variously described as both beautiful and creepy, something of which I’m rather proud. It was another weekend project, an experimental intervention rather than a practical tool. By clicking on eyes and faces, you can find your way to newspaper articles, but that’s not really the point. I was hoping to say something about the fragility of our connection to the past. We glimpse past lives through tiny cracks in the walls of time. These moments may be fleeting, but they can also be full of meaning.

So I kept harvesting faces, and I’ve now got about 6,000 from the newspapers from the 1880s through to 1913. And if you’d like to play the full dataset is available for download from the data-sharing site Figshare.

I also built my own face API to encourage further experimentation. While services like Face++ have APIs that take your face and pull it apart, mine just gives you random faces from the past. That’s all.

Most recently, I used my collection of faces to create a Twitter bot called The Vintage Face Depot. Tweet a picture of yourself to the bot, and it will send you back a new version of yourself in which your face is overlaid with a random visage from my extensive range of vintage faces.

Tweaking the transparency means that the face start to blend. You are neither yourself nor them, but someone new. Each face replacement also comes gift-wrapped with a link to the original newspaper article. The Vintage Face Depot tells you nothing new about yourself. I built it about the same time as Microsoft launched their How Old bot that uses machine learning to estimate your age. Face Depot does nothing clever and yet sometimes the results are uncanny, even unsettling. Microsoft may be able to tell you how old you are, but Face Depot asks who you are, and pushes you in the direction of a past life linked merely through chance.

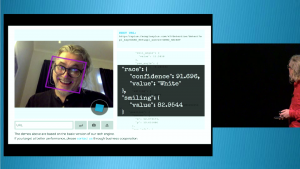

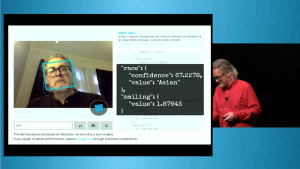

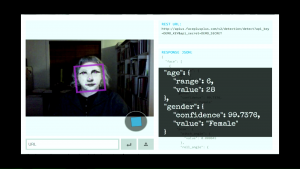

Of course, the next obvious step is to feed the results of the Vintage Face Depot to the How Old bot, or indeed to Face++‘s API:

In a similar vein, the developer Kurt Kaiser has been pitting neural network against neural network, altering images of himself using Google’s Deep Dream and uploading them to Facebook for DeepFace to analyze and tag.

Digital artists like Adam Harvey have reverse-engineered facial detection algorithms to devise anti-surveillance fashion styles. He shows how you can use make-up to disrupt key regions of your face such as where your nose and eyes intersect, and effectively render your face invisible. From face, to anti-face.

While none of these intervention provide a detailed critique of state surveillance, they do highlight the constructed nature of these technologies. By playing around with their parameters, we understand better how they work. (And that last sentence was modified to be more family-friendly.)

But what’s the role of cultural heritage organizations in all of this? Libraries are already leading the way in supporting online privacy. But leaving aside the whole living in a surveillance state thing for a moment, these technologies don’t just find faces, they reduce us to a set of external characteristics. We become what they can measure.

Researchers are currently investigating how facial detection systems can be used to identify depression. The aims are worthy, of course, but it’s not hard to imagine how, like 23andMe, such systems could be used to discriminate rather than support. Other studies have explored whether human observers can tell if you’re gay or prone to infidelity by looking at your face. Anyone remember phrenology?

With measurement comes the power to categorize and control. These are technologies that enable us to be judged at a distance, to be identified as a threat or a sales opportunity just by the way we look. Facial recognition takes this further. Not only can we be reduced to a set of externally-verifiable measurements, but these measurements are assumed to somehow constitute our identity.

So running Face++‘s API across a large photographic collection to identify, for example, pictures of women, seems like it could be a really useful thing to do. But we also know that the male/female binary is hopelessly inadequate in describing who we are. And identifiers are not the same things as identities.

Cultural heritage data is gloriously messy. Even as we try and wrangle it to fit our systems, we recognize the resistance as something profoundly human. Against the power of surveillance, both for security and for sales, we have the opportunity, the obligation to celebrate this complexity, to deny the meaning of measurement. You cannot know me from my face. My identify can not be captured in your database.

Let’s use Facial detection to enrich our metadata, but let’s also work with artists, developers, and activists to challenge the technology’s embedded assumptions about the perfect face.

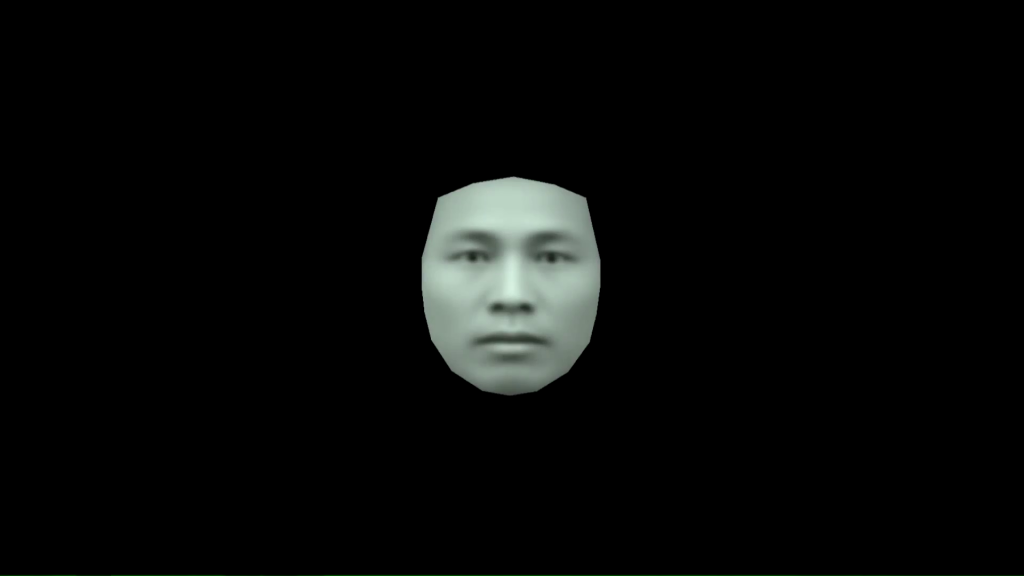

Four years ago, I showed you our wall of faces. A few weeks ago I took those 7,000 photos and ran them through a program that averages facial features. I expected to be critical. I expected to be annoyed. But instead of seeing some algorithmically-generated nonsense, I just saw a person.

And there’s power in that.

Thanks.

Further Reference

Tim’s own posted transcript of this presentation. (Not discovered until nearly completed here.)