Richard Sennett: …you today about what seems to me to be the most urgent problem that we face socially in cities, which is how can those who differ live together in the same place. It’s a problem theoretically raised by Immanuel Kant in a famous statement which says that the crooked timber of humanity cannot be made straight. Which doesn’t mean that Donald Trump can be corrected. But it rather means that it is impossible to find through verbal means, through talk, through discussion, a way for people to arrive at kind of mutual tolerance, at a kind of common understanding, which straightens out their differences. Or at least this is how Kant has been read after his time.

And I’ve asked myself whether that proposition that people’s differences cannot be accommodated, what that has to do about planning. Does that mean that planning a city where people live together is a hopeless enterprise?

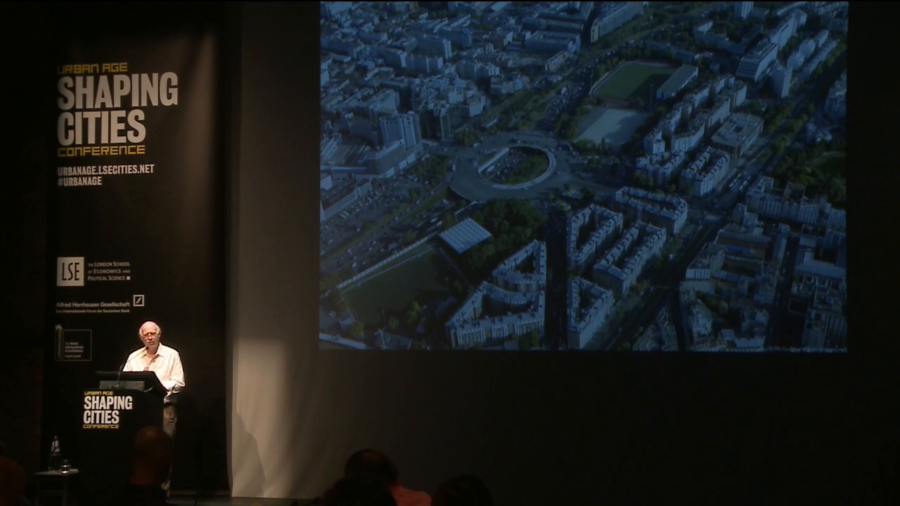

I wanted to come back to this image that Jean-Louis showed this morning because in a way it represents one answer to Kant’s question. It’s what’s sometimes called the good fences argument, or in this case the good highway argument, which is the only way for people who differ to live together is by separating them. And that’s an argument that’s made in the social sciences by various people now who are arguing that basically what the city should be is a series of fragments of difference in which the different groups do not intersect because nothing can be made straight by putting them together.

So what Jean-Louis has shown us is an answer to Kant’s question, and it’s a wrong answer. In my view, what an open city means is that people are exposed to one another. That that highway is taken down or bridged in such a way that people can live together without having to exchange verbally. That’s my idea of the open city, that it’s a place where physical presence with the other, and comfort with the physical presence of the other, does the work of allowing people to live together even if they are not engaged in the process of negating their differences.

I want to emphasize this is not a solution. There are no solutions. That’s a [planner?] fantasy: you have a problem, for every problem there’s a solution. If there’s isn’t a solution, there isn’t a problem. I don’t think that way. And the essence of the open city approach is that there are [indistinct] problems which leave the problems there, but at least in which the agency of planners and the public is engaged in trying to recognize that there is something that is difficult, and rather than say, “What can we do?” say, “At least we can do something physical.”

In my view, there are three ways in which the Kant problem can be addressed through planning. It first can be addressed through making porous edges, which is another reason I wanted to show this particular image. The essence of the uses that we’ve made of traffic in cities and of mobility more generally is to make them impermeable boundaries. There is no exchange possible under a physical condition like that. And I think one of the principles of open city design is to try instead of looking at boundaries, look at ways of making porous borders between differing communities, ethnically as well as class borders, at which the edges become places of physical presence, co-presence, and even physical exchange.

Planning in New York in the 90s, we had this— Always, when we looked at the very sharp boundaries between racial communities in New York City, what could we do to promote “integration.” And we learned that that word, integration, was the wrong way to do this. We should have been instead thinking about where the edges of these racially-segregated communities (which were also ethnically segregated), where we could locate physical resources like schools or health clinics that obliged people to be in the same space with those who differed.

A second principle of open city planning that addresses the Kant problem is the issue of synchronous space. Which is a very fancy way of saying that mixed uses do not necessarily mix people. If you have a city which during the day is all about people going to work and then at night there’s a transition where it’s all about partying and drinking (all those other good things that we should be doing now), and that the one function succeeds another, you do not have, in my view, the kind of mixture that allows people to gradually feel that they are comfortable or able to manage difference. They have to happen at the same time.

Again I refer to what we did in New York. We tried to put— For instance, in the late 80s and 90s, we tried to put AIDS clinics in the midst of shopping centers. So while you were shopping, you’re seeing people who are ill. You’re in their midst. And that is a procedure that has continued in New York by putting old age homes in shopping districts, and conversely putting into public housing lots of non-residential activities which happen at the same time and bring very different kinds of people together.

The third and probably the most complicated way of open city design which addresses Kant’s problem is incomplete building. You have a great example here of physically how to do this in the Aravena projects which build half a good house and people complete the other.

Extended more largely, incomplete design involves the kinds of experience of territories which feel underplanned, and which people colonize because their uses have not been fixed. That might seem to belong to the non-planned city, as Joan Clos was talking about. In my view, it takes planning to leave something incomplete. That is, it takes a master plan rather than any kind of spontaneous local activity to make a city incomplete, where people can colonize places where they don’t belong, or use them for uses that aren’t initially evident. You can’t rely on localities for incompleteness.

So these are the three principles of open city planning that address Kant’s problem. That they are porous borders rather than boundaries. That there are mixed uses which are synchronous rather than sequential. And when there’s incompleteness that is made by design rather than trusting to spontaneous local activity alone. And if those three principles were followed, we could erase this image. Thank you very much.

Jose Castillo: Thank you very much, Richard. Jean-Louis?

Jean-Louis Missika: Thank you very much, Richard. Of course I cannot answer the question. But I can put some ideas on the table in order to have a discussion, a conversation, about what is the main subject of your speech, which is urban planning can do something to the physical organization of the city. But, people are not things. They are not objects. They can feel. They can accept. They can refuse. And of course, when they have a lot of very important differences in opinions, in religion, in beliefs, they can disagree to living together.

First of all, I want to stress one point which is important in the theory of opinion. Extremization and radicalization of opinions and beliefs occur when people are not confronted with adverse opinion. And I think it’s very important nowadays, because this is the main problem we have to manage in a city like Paris or a city like London. The ring road, the highway we have seen in the map… The ring road is not only a physical frontier. It’s also a social frontier. And of course the question of integration is very complex.

But in a global city, confrontation of opinion, beliefs, and values is absolutely necessary. The strength of a city is directly related to this kind of confrontation of opinion. And we know that in cities where people are not confronted with different kinds of opinions, radicalization is the result. For example, In France when you are looking at the votes for the extreme right, for the Front National, you see that the vote is highest in the cities where you have no immigrants at all. And it’s the lowest in the cities where you have more important figures of immigrants, like Paris. In Paris, the National Front is very weak.

But if you ask people if they agree to be exposed to opposite beliefs or values, the answer is obviously no. They don’t want to do it. They don’t want to do it, as Paul Lazarsfed has shown eighty years ago in The People’s Choice about voting. And I think the question is not only a question of social networks, Internet, and so on. It was exactly the same in the age of television, and it was exactly the same in the age of the printing press. It’s a question of how difficult it is to be confronted with a vision which is so different from my vision. And of course everybody in his everyday life is in this situation.

So it means that of course urban planning is not enough. Urban planning is a necessary condition, but it’s not a sufficient condition. Why? Because with urban planning, you are opening the frontier, the physical frontiers. And this is the main condition to have this social melting pot, social confrontation, which sometimes is very violent but creates the vivre ensemble, living together, of a global city. And what you need is first of all creating these bridges between communities, and after that seeing what is possible to do in terms of education, in terms of employment, in terms of social relationships between these different communities. But what I think is that if you don’t make the first step, which is which kind of city you want to design in order to create social mixity, functional mixity, and circulation of people, fluidity between different places, you cannot do the next steps.

And another very interesting figure is that the places where—for example in Paris, the radicalization of population is at the highest level in the places where you have no public transportation. Because people feel that they cannot get out of their ghetto. They cannot get out of their territory. So, if I am a territory and I am closed in this territory, it’s like a jail. So I act like a prisoner.

So I think that urban planning is not the answer. And as a sociologist I understand that you say that. But it’s part of the answer, and I think it’s very important. Thank you.