B. Cavello: Thank you all so much. So you’ve been hearing a lot about the Navy SEAL and I just want to say that that is…not me. Our team is an interesting one. Peaks unfortunately couldn’t be with us here tonight. But we’re a small team, although the image here might mislead you.

We are small in part because we’re working on a pretty controversial topic, and that is the topic of algorithmic warfare. That’s what brought us together. And in particular, when people hear that term they think of a lot of different things. They may think of this guy, the Terminator, Skynet. Thinking about robots, and here in Cambridge, Boston Dynamics.

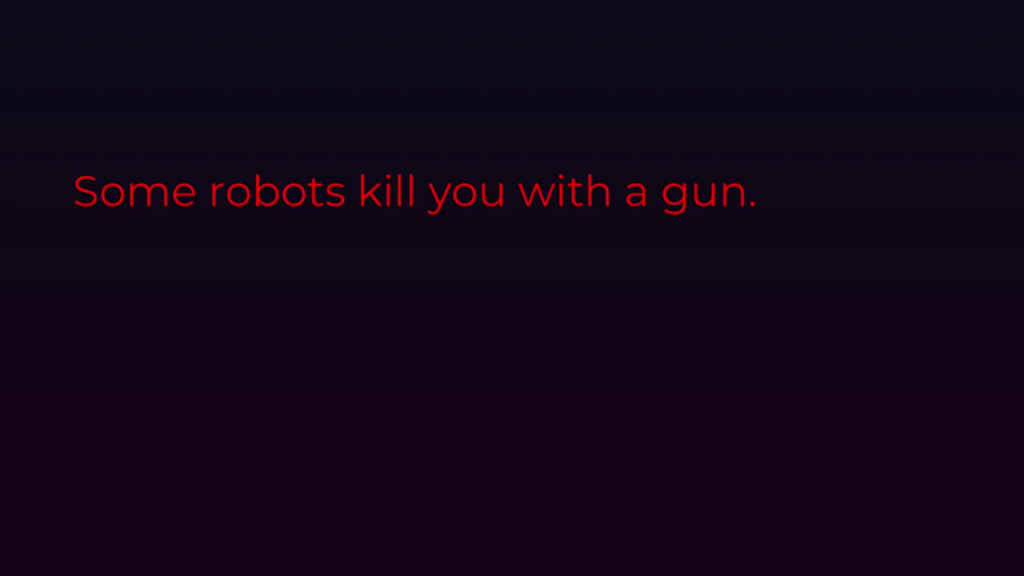

But we actually wanted to challenge that paradigm a little bit. When we began this project we were looking into what is the role of AI in warfare, what is algorithmic warfare. And we came to the conclusion that there’s kind of this interesting misunderstanding, right.

So there’s a really big effort underway to address the dangers of these kinds of robotics. And it’s real, right. That’s a valid effort.

But there’s also this very real threat that a lot of people kind of overlook, which is that at the end of the day it doesn’t actually necessarily rely on a robot being the delivery mechanism of violence if you’re still being targeted.

And so that’s really what inspired this project. We wanted to look at how surveillance, how these algorithmic decisionmaking systems and surveillance systems feed into this kind of targeting decisionmaking. And in particular what we’re going to talk about today is the role of the AI research community. How that research ends up in the real world being used with real-world consequences. And then talk a little bit about what we found in our investigation of the space and what we invite you all to join us in doing as we move forward.

So, to take a step back, there’s a pretty diverse crowd here so I just want to contextualize a little bit about what we’re talking about when we’re talking about this kind of algorithmic surveillance. Here, you’re seeing depicted a video surveillance system that has image recognition technology. So it’s identifying, it’s putting boxes around various people and vehicles and so on. So we’re looking at a couple of different types of systems here: computer vision systems, systems that can listen to voice or audio, as well as systems that may look at social networks or things that we post on social media to come to conclusions about whether or not we fall into a certain group.

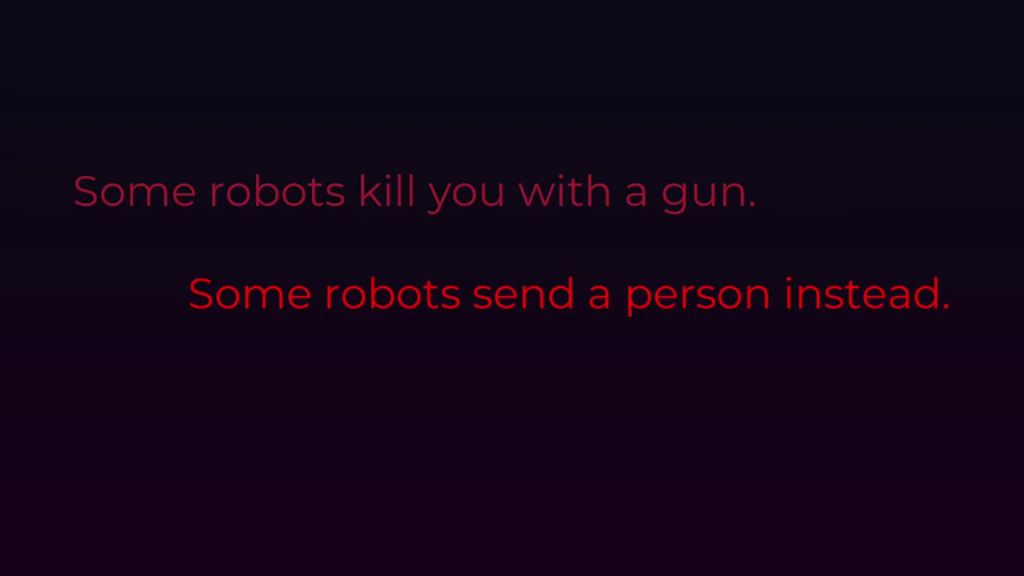

Now, in this project in particular we’re talking about an incredibly rich and interrelated system, and I’ll talk a little bit about this data visualization in a second. But I want to first just contextualize that when we’re talking about this research community, we’re talking about a lot of different players in a global ecosystem. And you know, as researchers we want to share, we want to collaborate, and that’s a beautiful thing. But what can be challenging about this space is that these threads of connection could lead to places that we didn’t originally intend and we may as researchers not have even being aware. And so our work in particular is exploring how some of those outcomes, how some of the end uses of research that may be done with the thought of being theoretical or benign can actually have real harm in our world.

So with that I’m going to turn it over to Carl.

Carl Governale: I’m Carl. I’m the one they’ve been talking about. And I’m going to teach you how to hunt people.

So, many practitioners in this space will often say that the technology, it just isn’t mature enough to be a true threat. You couldn’t use facial recognition alone to build this target deck. And I promise you that grossly undermines the threat. How you hunt people is actually with a series of overlays; you don’t use one individual technology, you use them to hone in and find the corollaries to build a smaller list, until you have your approved target deck.

So, if I wanted to identify all of the protesters in Hong Kong yesterday, I wouldn’t just use facial recognition of CCTV camera footage. I would take that and put that on an overlay of metro cards used in the subway system in Hong Kong, right. And that might give me a more accurate deck to begin our interrogations.

So, jumping off of that short example, a quick deep dive. So non-exhaustive, but if you’re not familiar with the Uyghur crisis in Xinjiang, China I’ll give you just a couple of soundbites. So, since 2014 the Chinese people’s war on terror has been a systematic effort to oppress the Uyghur population, which is an ethnic minority in China that practices Islam. Roughly 10 million individuals, so 1.5% of the Chinese population, but also does account for 20% of all arrests in China. Consequently there are over one million Uighurs currently assessed to be interned in Xinjiang Province in re-education camps. These are the camps of Holocaust lore, where there’s killing, torture…primarily this method of assimilation via submission.

It’s a heavy workload; genocide is tough. So the People’s Liberation Army has leveraged the tech industry. So this region, this small province and cross-section of society accounts for about $7.5 billion of the security industrial complex in China. And they leverage both facial recognition, voice recognition, and other forms of AI to apply lists of people who are either demonstrating Islamic practice, or they demonstrate phenotypic features of this ethnic minority.

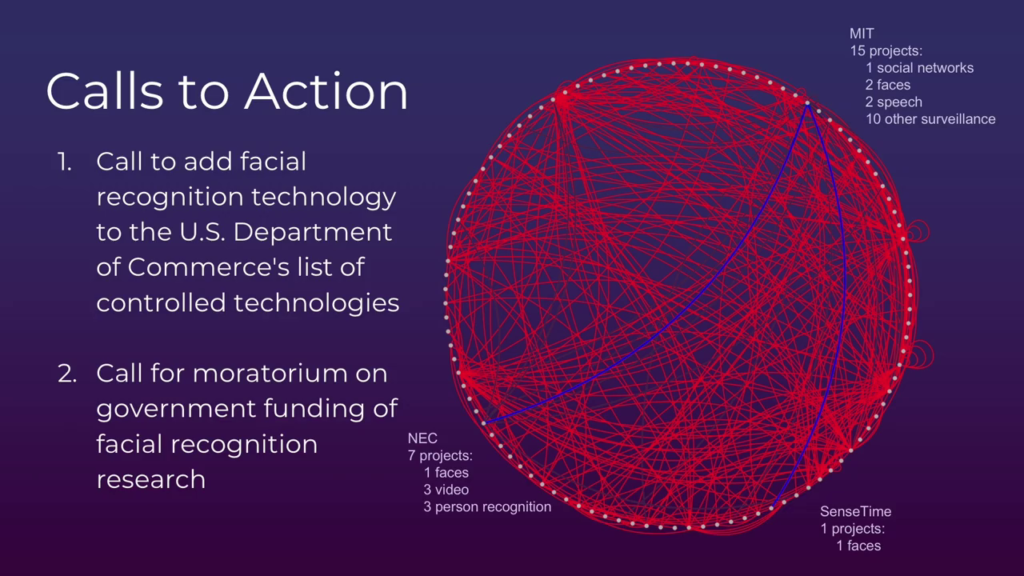

Now, where you stand depends on where you sit, and in the interest of positionality we’re going to bring this home to MIT. A bunch of institutions in America here service key nodes in the surveillance supply chain. But here at MIT, through our research we found there’s about fifteen projects ongoing in some way, shape, or fashion for surveillance-type of technology.

So the nature of this ecosystem lends itself to this really complex interdependence. So the research ongoing here at MIT is done in affiliation with or with funding from both private and public institutions. So a private institution would be NEC is a Japanese-based security firm that’s…basically their product is predictive policing. We use it here in the States, it’s used in the UK.

Other companies that have contributed funds to this type of research at MIT include SenseTime and iFlytek. Those two companies are both implicated in the provision of services in Xinjiang province.

Also, one fantastic supplier, if you can use that term, of funding for this type of research is the US government. So, these same researchers that are linked to these companies are also receiving funding from DARPA, Office of Naval Research, Marine Corps Warfighting Lab, and Army Research Lab. Occasionally they actually appear on these same publications in the acknowledgments section.

Cavello: So, we wanted to present this, and for some folks in the room it’s probably new information, but we are not the first people to talk about this issue. The issue of surveillance tech is really important and it’s been an emerging and burgeoning conversation here in the United States as well as around the world. There are actually folks in the room here who are experts in the topic. But really there’s this common theme here, which is that researchers and product teams have an important role to play in actually helping to think about how this technology is used, or prevent it from being used irresponsibly. And in particular I wanted to talk a little bit about what we’ve covered so far.

So, we’ve looked at, in reality thousands of different projects and contracts from the US government or journal publishings. We honed that into a couple-hundred list of surveillance-tech-specific. And then we ultimately came down to about sixty-five research institutions here in the United States, with forty-nine funders, as Carl said, ranging from Chinese surveillance tech companies, to US surveillance tech companies, to our own US government. And they covered a broad kind of breadth of different types of surveillance research, including facial recognition, social network analysis, and person re-identification—which for me was a new phrase—which is a little bit like what Carl was talking about at the beginning the presentation here.

So, what we’ve been doing is putting together all of this information and really trying to literally visualize it. So I know this kind of looks like scribbles on the screen here but this is a data visualization we’ve been putting together representing all of those different connected nodes. And ultimately what we would like to do is to be able to move forward on a project that has a better understanding of the reality of what’s on the ground. We want to know, is this data reliable? Can we get access to more information? For instance, today we were only using public sources. And we also want to really involve the voices of the people who are developing these tools. One of the common themes in the work that we were doing to research this project is that we found that a lot of the people involved actually didn’t know how their work was being used in the world, and that is both concerning but also a really exciting opportunity for us to educate and do better.

But ultimately there are also a couple of things that even if you’re not a machine learning researcher, even if you’re not in this kind of surveillance tech space, there are a couple of key points that we would really like you to push on as you’re having conversations with your representatives about what we can do about surveillance tech, at least here in the United States.

Governale: So this is where we go from fact to opinion, so the opinions herein are not representative of the US government. But they are ours.

So, call to action. Two points that through our research we feel like we can apply some leverage to this problem set and ideally make a difference rather than admire this problem.

First is Department of Commerce. That’s the office that holds the export administration regulations. So these are essentially regulations that govern the export of commodities to include dual-use technologies and software. So in adding facial recognition and surveillance technologies to that list, it would be a forcing function for anybody that’s in this complex ecosystem to have to apply some level of risk mitigation and threat modeling to their decision calculus.

And then finally, we should probably call for a moratorium on US government funding for the research of these technologies. Not saying that the requirements are not going to be fulfilled by the US government. But the acquisition of this technology should probably happen in a highly-regulated commercial market as opposed to being directly funded. Because the complexity and the low density of these skill sets just don’t lend themselves to ethically-sound and transparent funding profiles. So let’s take that basic research funding and put it somewhere else. Thank you.