Good afternoon, MozFest. I’m Simone, and I research and think about and sometimes write about surveillance, and also teach at the University of Texas at Austin. The way I approach surveillance can be encapsulated in this image right here.

This is a screen cap of a video from 2009. It is of Desi Cryer and Wanda Zamen. They call themselves Black Desi and White Wanda in the video. And they’re two workers at a camping store in Texas who are testing out a new HP facial automated tracking system with the computer. And one of the things that happens in this video is that Black Desi says, “Watch what happens when my blackness enters the frame.” And he’s talking about the camera’s seeming inability to follow him or to pan or to zoom and follow his face. But when White Wanda gets in there, the facial tracking system works. And so this question of what happens when blackness enters the frame can kind of neatly encapsulate the ways I’ve been thinking and trying to talk about surveillance for the last few years.

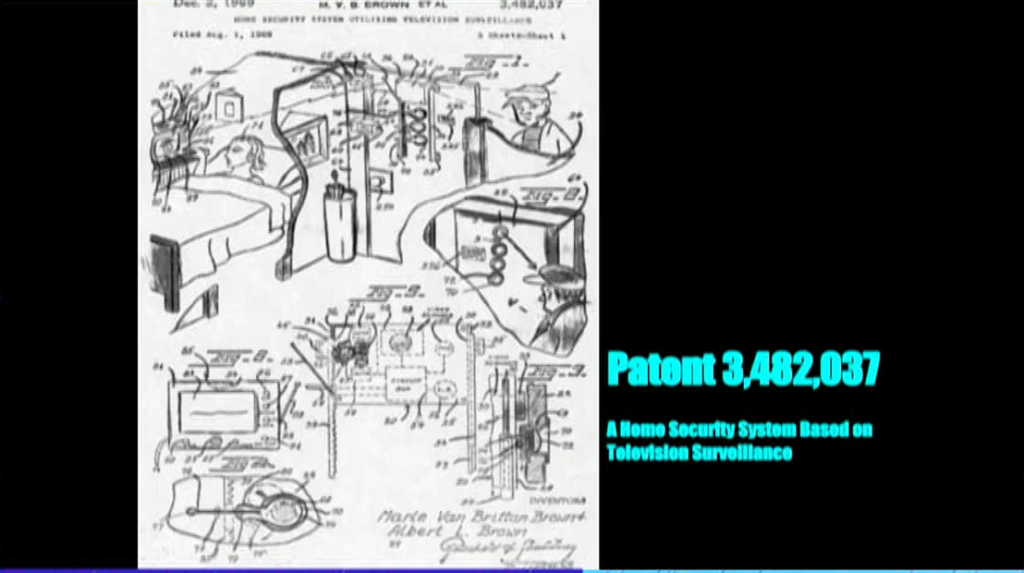

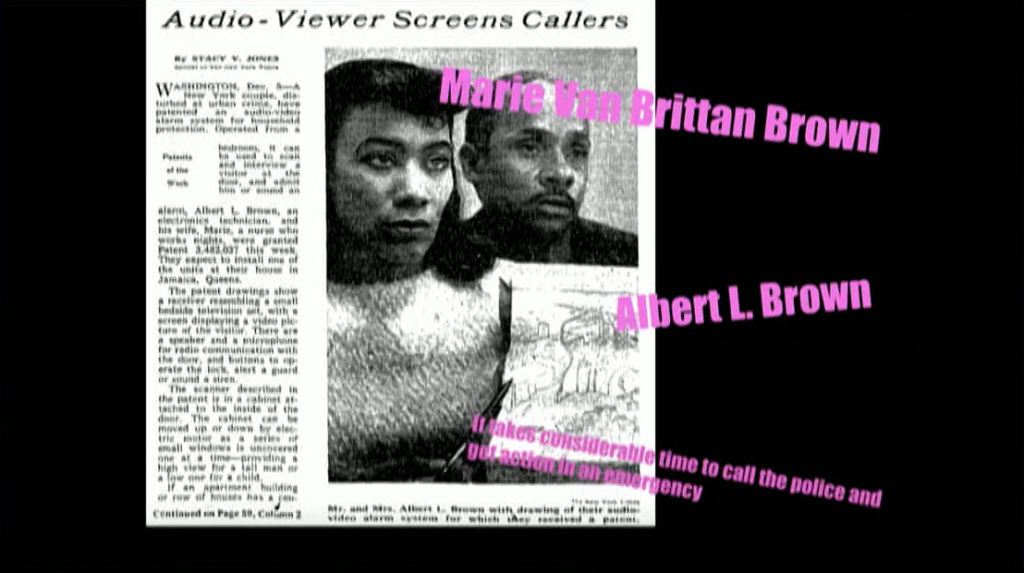

And so for example there is this. In 1966, Marie Van Brittan Brown, a nurse living in Queens, New York along with her husband Albert L. Brown invented what they called a home security surveillance system. This was 1966 CCTV. So Marie Van Brittan Brown was a nurse, and she would often travel home late at night.

It was quite intricate there. It consisted of a doorbell of that she could unlock the door from her bed, audio intercom, and you can see this as a precursor to modern video doorbells or other types of home surveillance systems.

And so I kind of also can see from the diagram the robber there— Well, you can tell it’s a robber I guess because of the striped shirt and the sparsely-populated beard and the hat. So you could almost think of it as a kind of abolitionist technology. She was really concerned about the slow police response to Queens and their home whenever people would call in cases of emergency. And so this do-it-yourself take on surveillance is one of the ways that I think about how black women’s work has been absented from surveillance technologies—how we think about them, how we theorize them, and in this case how they are created. So one of the key things I do is I ask how our past can allow us to think critically about our present.

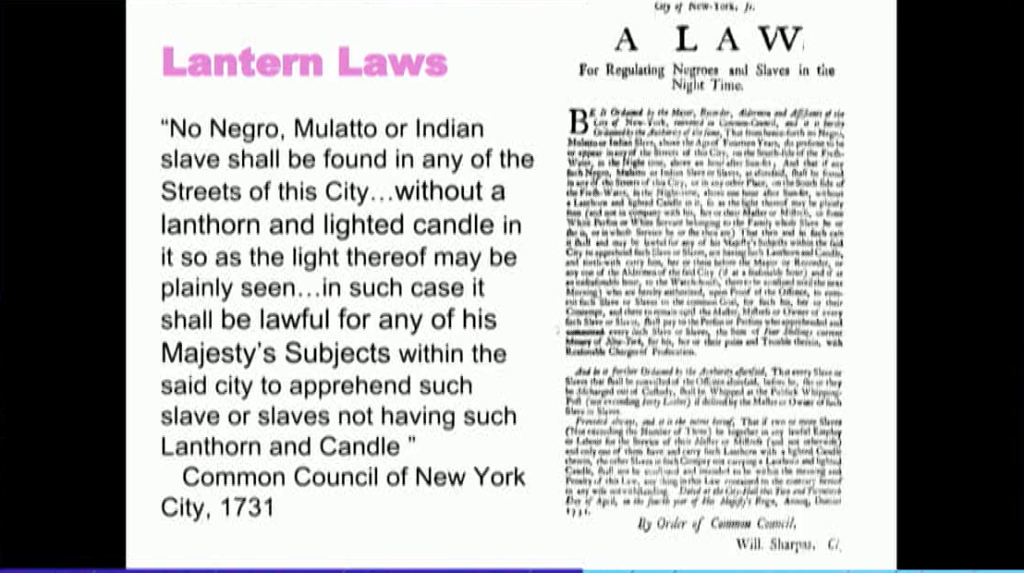

And so on this is an image from a law from New York City in the 1700s. They’re lantern laws that required that black, mixed-race, or indigenous people, if they were to walk around the city after dark and they weren’t in the company of some white person, they would need to have with them a lit lantern as they moved about the city. If not, they could be taken up, arrested, and put in the gaols until some “owner” will come and get them. They could also be subject to beatings.

So this makes light a surveillance device, a supervisory device, but it also created certain humans as the lighting infrastructure of the city. And so I took this to think about 200 years later or so, we have omnipresent policing practices where light is used. High-intensity floodlights are shone into people homes as a form of surveillance, as a form of protecting and lighting up certain spaces.

And so you see here this image is somebody who had took to Instagram to talk about the violence—thinking about the noise pollution or the sound pollution that comes from a large generator. So just this summer, the American Medical Association put out a warning on the effects of LED lights [via], high-intensity lights in the city, that might have effects in terms of changing humans’ cardiac rhythmicity, intense glare, and also heart palpitations.

And so when I think about how the past allows us to ask critical questions about our present, I think about this lighting technology, this infrastructure, and the ways that 300 years earlier in New York City, black, indigenous, and mixed-race people were called upon or instructed to carry lanterns with them as they moved about after dark. And you can think about what type of human life is valued as, or devalued as, infrastructure.

So for example in Austin, Texas in 2012 at the South by Southwest Festival, one company took it upon themselves to create homeless hotspots, where people who were made homeless or underhoused were fitted with WiFi devices so that they could then be homeless hotspots for people who needed to have their tech readily available.

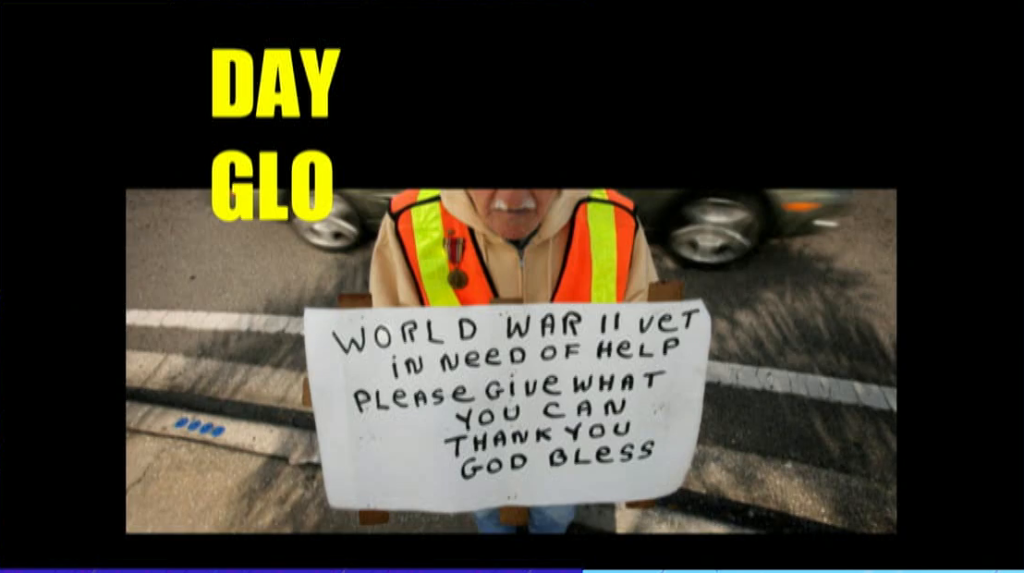

You have another way in which light is used as a form of discipline. In certain cities like Durham, North Carolina and also Tampa, Florida, there are ordinances put in place that mandate that people who are panhandling or fliering are supposed to wear phosphorescent or glow-in-the-dark vests if they are to do so.

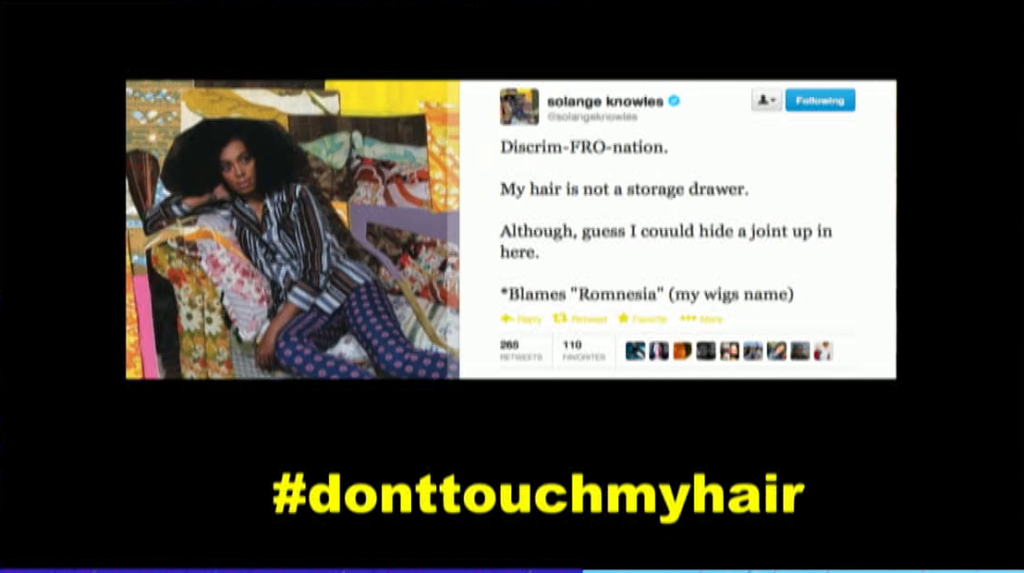

And so another thing that I looked at when I think about surveillance is the ways in which black women negotiate the TSA—the hair searches as they go through the airport. And they start with this: Solange Knowles, sister of Beyoncé, took to Twitter a few years ago to complain about the discrim-fro-nation that she—when she was subjected to a hair search by the TSA. And so you see that this social media site becomes the site of critique of state practices. And many others continue to do so. They point to the ACLUs, they tell each other to know their rights, and also form a generalized critique of surveillance by way of Twitter and other sites.

But I’m going to return to Black Desi and White Wanda to talk about biometric technology. You can think of biometrics as doing a few things. They could be used for identification—so who are you in the face in the crowd, or even if you’re enrolled in a particular biometric database. They could also be used for verification—so answering the question “Are you who you say you are?” And also could be used for automation, in the case of Black Desi and White Wanda. So automation—is anyone there? And I looked at earlier uses of biometric technology to see the ways in which people critically engaged and challenged this marking of identity on the body.

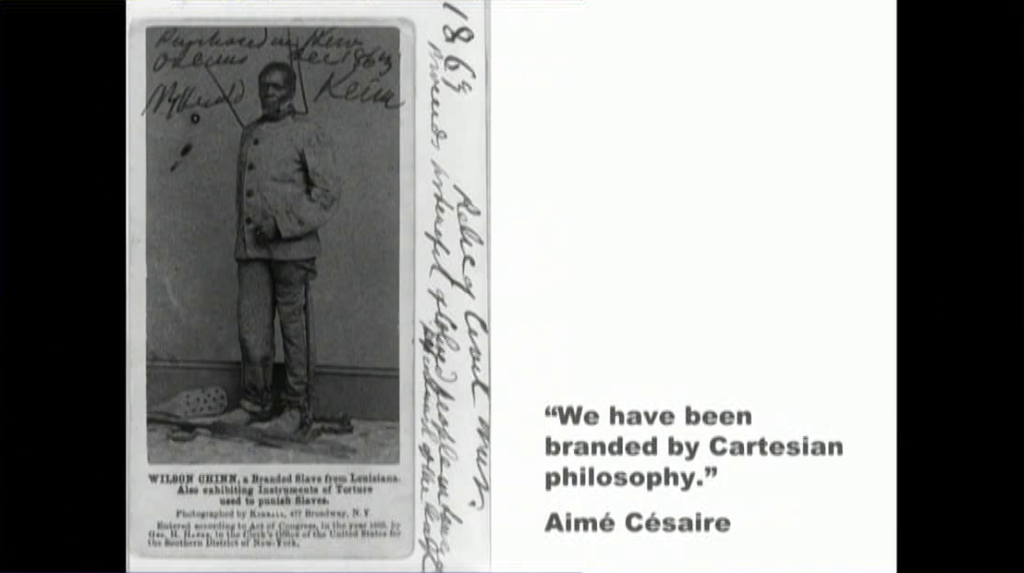

One of the ways that I do that is to historicize biometrics through thinking about the branding of enslaved people. This is a carte de visite of Wilson Chinn from the 1860s. And you can see around his neck he has a metal collar. It’s called a longhorn. What you can’t see in this image is on his forehead he has a brand, “VBM” branded on his forehead. And so he liberated himself and escaped from slavery, but seemingly with this brand it was impossible to escape this marking on his forehead. And you can think about this marking as a traumatic head injury. And this is not to say that branding of enslaved people and biometrics technology are one and the same, but it’s to ask critical questions about how biometrics, if you think it’s simply as body measurement, has been applied and used and resisted historically.

“Whites Only?”; YouTube user Teej Meister

And so we have this image from a screengrab from last year of a sink that seemingly did not work for dark hands but worked for light hands.

Jacky Alciné, Twitter

Or we have this image here, also from last year, of another automation technology where someone had uploaded images of his friend to a Google photo tagging or photo identification site, and [which] continually categorized his friend, a black woman, as a gorilla. And so we have to continue to think about what kind of training data is used to populate these types of technologies.

Facebook, Instagram, Twitter Block Tool For Cops To Surveil You On Social Media; Study: Face Recognition Systems Threaten the Privacy of Millions; Is Facebook’s Facial-Scanning Technology Invading Your Privacy Rights?

I’m going to close with this right here. So, a couple of weeks ago at the Georgetown University law school, they released a 150-page report on biometrics and facial recognition technology. One of the things that they found in this report is that in the US, over half of adult Americans have their biometric facial features in a database—one or more—that can be accessed by the police. And you can find this at www.perpetuallineup.org.

And so, when we think about the ways that the business end of surveillance meets the business end of policing, I want us to continue to be critical about biometric technology, about algorithms, and who holds the proprietary data when people’s bodies, and parts and pieces of their bodies, or performances of their bodies—their biometrics—are held by—whether it’s Facebook or whether it is other types of sites and policing.

So what I will do is close right here. But I will close with the question that I started with to think critically about what happens when blackness enters the frame. Because I think it offers us some productive possibilities for our future. Thank you.

Sarah Marshall: So, anybody got any questions for Simone?

Audience 1: Seeta Peña Gangadharan, London School of Economics. So I really enjoyed your talk. Thank you so much. I think it’s really important that these kinds of conversations are had in a setting that is historically not inclusive of conversations about race and the intersection of race and technology. So thank you.

But one of the things that I’m wondering about—because as Sarah had said when she introduced you that you’re sort of at the intersection of privacy, security, and digital inclusion. I was just wondering if you could expand upon the third aspect of that, digital inclusion, and maybe touch upon some of these positive or transformative things that you were alluding to at the end of your talk with your provocative question.

Simone Browne: Okay. So I think that the TSA example of people talking to TSA is transformative. Someone linking on Twitter to the Know Your Rights campaign is talking about not only using these technologies to think about what happens with the security theater in an airport. And so I think of myself as more of a gadfly. I think we have a particular set of skills, and mine is not—you know, I’m not one of the people that are creating or developing these technologies. So I left with that thing about what happens when blackness enters the frame, and I think that black women using their Twitter to formulate a critique of the state is about inclusion—using the digital to have a more equitable kind of way in which we move through an airport space.

And so my suggestion is not to say well, let’s teach young black girls how to code so that they could be more easily exploited when they get older into the digital labor force. But to continue to have these types of discussions about what’s at stake when 50% of American adults have their face in a database that is accessible to the police, and when we think about the over- and hyper-policing of black people and people of color within the US and globally, what does this mean for the ways in which biometrics could be linked to criminalization practices.

Marshall: Good question. Anybody else got a question for Simone? Yes, I can see a gentleman at the back.

Audience 2: So, a couple of the examples you gave—the sink, the facial recognition algorithm, and I think I read that Microsoft Kinect has faced similar issues—are quite obviously not malice, most likely, but rather… Microsoft, for example, in the Kinect case said, “Well, we tested it on our employees who were like 95% white.” So obviously it’s clear that when testing these things, things like QA departments will have to say, “We can’t do everything. Some people are handicapped. They might be hard to recognize if they’re facially deformed or something like that. But there’s a bunch of races and things like that that obviously there’s a lot of people that are going to be using this. We should be testing with that.” Do you see a change in that? Do you see companies being more aware of this when they’re working on biometrics?

Browne: Yeah. And I think there’s a lot of capacity with how these companies do and create and research and develop these things, so I don’t necessarily have the knowledge to track whether there’s a change. But it seems to me that the way that the white body becomes read as the default setting or produced as neutral, as a kind of prototypical whiteness, continues to happen. And so you would have someone use YouTube to say that a sink doesn’t work in 2015. Or in 2009 say that the camera doesn’t work. Or Kinect, or the one with the gorilla in 2015.

So every year or so, it seems that the same type of white neutrality seems to be used as the kind of prototypical body when developing these things. And so it comes to the consumer or the users to use a place like Instagram, or Twitter, or Facebook to offer a critique of who’s entering the conversations and the development of these technologies. And so perhaps it might not necessarily be the consumer’s job to show people how anti-black these technologies are.

Marshall: And to pick up on your point, then, part of the problem is diversity in technology, in the work force, do you feel?

Browne: Yeah, I guess it could be diversity. But we could have a diverse amount of people and we could still have an anti-black frame into how these things are developed. So I think it needs diversity but also equity as well.

Marshall: Okay, any other questions for Simone? I have one more question I’m eager to ask. In your university—I mean, you’re here talking to a bunch of technologists, largely. And I’m guessing that the subjects you teach back in Austin, I’m guessing that you’re mainly not talking to technologists. Or do you talk to technologists about this, too?

Browne: Yeah. So, I have a variety of students in my class, from electrical engineering to women’s studies and also black studies. And so we can come together in a quite collaborative and interdisciplinary way to talk about these technologies, yeah.

Marshall: Great. Okay, if there are no further questions then let’s thank Simone.

Browne: Thanks so much.

Marshall: Thank you.